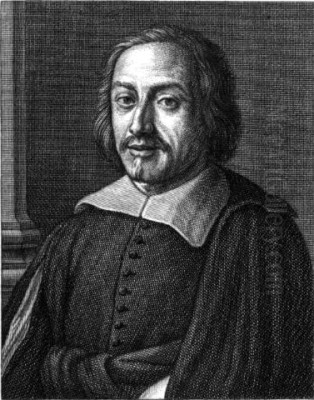

Matteo Rosselli (1578-1650) stands as a significant and prolific figure in the landscape of early seventeenth-century Florentine art. His career bridged the late Mannerist tendencies prevalent in Florence with the burgeoning Baroque style, making him a crucial transitional artist. Known for his gentle disposition, devout faith, and unwavering dedication to his craft, Rosselli produced a vast oeuvre encompassing altarpieces, frescoes, and portraits, leaving an indelible mark on the artistic fabric of his native city and influencing a generation of painters.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Born in Florence in 1578 to Alfonso Rosselli and Elena Pilai (referred to as Eco Pilai in some sources), Matteo Rosselli's artistic journey began at a young age. He entered the workshop of Gregorio Pagani, a respected Florentine painter who himself had been a pupil of Santi di Tito. Pagani's studio was a crucible of the "Counter-Maniera" movement, which sought to reform the perceived artificiality of late Mannerism by returning to clarity, naturalism, and direct emotional appeal, often drawing inspiration from earlier Renaissance masters.

Under Pagani's tutelage, Rosselli absorbed these reformist ideals. He was also profoundly influenced by the High Renaissance master Andrea del Sarto, whose balanced compositions, soft sfumato, and harmonious color palettes left a lasting impression on Rosselli's early artistic sensibilities. This grounding in Florentine artistic traditions, emphasizing drawing (disegno) and compositional clarity, would remain a hallmark of his work throughout his career. In 1599, a testament to his burgeoning skills and recognition within the Florentine artistic community, Rosselli was admitted to the prestigious Accademia del Disegno, the city's official artistic academy.

Roman Sojourn and Broadening Horizons

The year 1605 marked a pivotal moment in Rosselli's development. He traveled to Rome, the vibrant epicenter of artistic innovation in Italy, to further his studies. For approximately six months, he worked in the studio of Domenico Cresti, better known as Il Passignano. Passignano, like Pagani, was a key figure in the Florentine reform movement and had also spent considerable time in Venice, absorbing the rich colorism of Venetian masters such as Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto.

Rosselli's time in Rome, though relatively brief, was immensely formative. He was exposed to the classical grandeur of ancient Roman art, the monumental achievements of High Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo, and, crucially, the emerging currents of the early Baroque. Artists like Annibale Carracci and Caravaggio were revolutionizing painting in Rome with their distinct approaches to naturalism, drama, and light. While Rosselli's style would not fully embrace the dramatic intensity of Caravaggio, the Roman experience undoubtedly broadened his artistic vocabulary and encouraged a greater sense of dynamism and emotional depth in his work. It was also during this period, or shortly thereafter, that Passignano entrusted Rosselli with completing some of his unfinished commissions following Passignano's own periods of illness or departure, a sign of the master's confidence in his pupil's abilities. This Roman sojourn also exposed him to the art of the Emilia-Romagna region, further enriching his palette and compositional strategies.

Return to Florence: A Leading Master

Upon his return to Florence, Rosselli established himself as one of the city's leading painters. His style, a synthesis of Florentine tradition, the reformist principles of his teachers, and the broader Italian influences encountered in Rome, found favor with a wide range of patrons. These included prominent noble families such as the Medici, the Corsini, and the Dragomanni, as well as numerous churches and monastic orders.

His workshop became one of the most active and influential in Florence. Rosselli was known for his meticulous approach to commissions, his reliability, and his ability to manage large-scale projects. His paintings from this period demonstrate a mature style characterized by clear narratives, graceful figures, rich and often refined color harmonies, and an adept use of chiaroscuro to model forms and create atmospheric effects. While sometimes criticized by later art historians for a perceived lack of bold originality or overwhelming power when compared to his Roman Baroque contemporaries, Rosselli's strength lay in his consistent quality, his narrative skill, and his sensitive portrayal of human emotion.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Matteo Rosselli's extensive body of work spans various genres, but he is perhaps best known for his religious paintings and large-scale fresco decorations. Among his notable early easel paintings are The Annunciation (1607) and The Last Supper (1607), which showcase his developing command of composition and expression. The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian (1618) is another significant work, demonstrating his ability to convey dramatic religious narratives with clarity and pathos.

Rosselli was heavily involved in major decorative projects for Florentine churches. He contributed significant frescoes to the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata, a key Marian shrine in Florence, and to the cloisters and chapels of Santa Croce, the burial place of many illustrious Italians. These large-scale works allowed him to display his skills in complex multi-figure compositions and narrative sequencing. For instance, his frescoes depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary or local saints were designed to be both devotional and didactic, engaging the viewer with their accessible storytelling.

His talents were also sought for secular decorations. A prestigious commission involved painting a series of historical portraits and allegorical scenes for the Villa di Poggio Imperiale, a Medici residence just outside Florence. Here, he depicted figures such as Emperor Charles V, Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici, and Cardinal Mattia de' Medici, alongside other historical and mythological subjects, contributing to the villa's opulent decorative program. His Triumph of David (c. 1621), now in the Palazzo Pitti, is a celebrated example of his ability to handle grand historical themes with vigor and decorative flair. This work, with its dynamic composition and rich coloration, exemplifies the Florentine Baroque sensibility. He also contributed to the decorations for the Casa Buonarroti, Michelangelo's family home, further cementing his status within the Florentine artistic elite.

Another interesting, though perhaps later, commission mentioned is the Archangel Michael (reportedly 1650, the year of his death), located in what is now the Museo di San Marco (formerly associated with Donatello's works in some contexts, but San Marco is more accurate for paintings of this era). His involvement in projects like the frescoes for the defense of the monastery of San Miniato al Monte, though perhaps less artistically central, speaks to the breadth of commissions he undertook.

The Workshop: A Crucible of Florentine Talent

Matteo Rosselli's workshop was a dominant force in Florentine painting for several decades. He was a dedicated and effective teacher, and his studio attracted a considerable number of aspiring artists. His pedagogical approach likely emphasized the traditional Florentine focus on drawing, combined with his own refined sense of color and composition.

Among his most distinguished pupils was Lorenzo Lippi (1606-1665), who, while developing his own distinct style characterized by a more pronounced naturalism and a somewhat purist aesthetic, clearly benefited from Rosselli's instruction. Lippi himself became a noted painter and poet. Another prominent student was Baldassare Franceschini, known as Il Volterrano (1611-1690), who would become one of the leading fresco painters of the Florentine High Baroque, known for his illusionistic ceilings and dynamic compositions.

Other notable artists who passed through Rosselli's studio include Jacopo Vignali (1592-1664), who developed a soft, devotional style; Francesco Furini (1603-1646), known for his sensual and enigmatic sfumato figures; and Giovanni Martinelli (c. 1600-1659), whose work often displays a Caravaggesque intensity. Cosimo Ulivelli (1625-1705) was another pupil who joined the workshop at a young age and continued to work in a style indebted to Rosselli. The sheer number and subsequent success of his students attest to Rosselli's importance as an educator and his central role in shaping the next generation of Florentine painters. He also collaborated with other artists on occasion, such as Giovanni Battista Guidoni, on specific commissions, a common practice for large projects.

Rosselli's Place in Florentine Baroque

Matteo Rosselli is rightly considered a key progenitor of the Florentine Baroque style. His art represents a departure from the elongated forms and complex allegories of late Mannerism, as exemplified by artists like Giorgio Vasari or Agnolo Bronzino, moving towards a style that was more naturalistic, emotionally accessible, and compositionally clear. He built upon the reforms initiated by artists like Santi di Tito, Ludovico Cigoli (a major influence on Passignano and thus indirectly on Rosselli), and his own master, Gregorio Pagani.

While the Baroque in Rome, spearheaded by figures like Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Pietro da Cortona, and Francesco Borromini, was characterized by exuberant dynamism and theatricality, the Florentine iteration of Baroque was generally more restrained and sober. Rosselli's work embodies this local character. His paintings possess a quiet dignity, a refined elegance, and a narrative clarity that appealed to Florentine tastes, which often favored intellectual rigor and decorum.

He successfully navigated the competitive artistic environment of Florence. While the arrival of artists from other centers, such as Pietro da Cortona who executed significant frescoes in the Palazzo Pitti, introduced a more robust and dynamic High Baroque style to the city, Rosselli maintained his prominence through his consistent output, his reliable workshop, and his deep understanding of local devotional and cultural needs. His art provided a bridge between the late Renaissance heritage of Florence and the newer expressive possibilities of the Baroque.

Artistic Influences, Collaborations, and Legacy

Rosselli's artistic DNA was woven from several strands. The foundational influence was the Florentine tradition of disegno, passed down from masters like Andrea del Sarto. His immediate teachers, Gregorio Pagani and Domenico Passignano, instilled in him the principles of the Counter-Maniera reform, emphasizing clarity, naturalism, and emotional directness. The brief but impactful Roman sojourn exposed him to the broader Italian artistic currents, including the classicism of the Carracci school and the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio, as well as the rich colorism of Venetian painting, often filtered through Passignano. Artists like Jacopo da Empoli were also significant contemporaries in Florence, working along similar reformist lines.

His influence on subsequent Florentine painting was substantial, primarily through his numerous pupils. Lorenzo Lippi, Il Volterrano, Jacopo Vignali, Francesco Furini, and Giovanni Martinelli, among others, all carried aspects of his style and teachings into their own successful careers, adapting and transforming them according to their individual temperaments and the evolving tastes of the mid-to-late seventeenth century. Through them, Rosselli's legacy was woven into the fabric of later Florentine Baroque art.

While he may not have possessed the revolutionary genius of a Caravaggio or the overwhelming grandeur of a Pietro da Cortona, Rosselli's contribution was vital. He provided a model of artistic professionalism, technical skill, and devotional sincerity that sustained a high level of artistic production in Florence for decades. His ability to synthesize various influences into a coherent and appealing style made him a cornerstone of the Florentine Seicento.

Later Years, Character, and Critical Reception

Matteo Rosselli remained active as a painter and head of his workshop until late in his life. He passed away in Florence in 1650, leaving behind a rich artistic heritage. Contemporary accounts describe him as a man of mild and pious character, dedicated to his family and his faith. This personal piety is often reflected in the sincere and accessible religious sentiment of his paintings.

Art historical assessments of Rosselli have sometimes been mixed. While universally acknowledged for his technical proficiency, his prolific output, and his importance as a teacher, some critics have pointed to a certain conservatism or lack of daring innovation in his work, especially when compared to the more radical developments occurring in Rome. However, this critique often overlooks the specific cultural and religious context of Florence, which valued decorum and clarity. Within this context, Rosselli excelled, providing artworks that were both aesthetically pleasing and spiritually edifying. His attention to detail, his skillful handling of light and shadow, and his ability to create harmonious and engaging compositions ensured his enduring reputation.

Conclusion: An Enduring Florentine Master

Matteo Rosselli was a pivotal figure in the transition from Mannerism to Baroque in Florence. His long and productive career, his influential workshop, and his numerous prestigious commissions solidified his position as one of the leading painters of his time in the city. He successfully blended the Florentine emphasis on drawing and narrative clarity with a richer, more naturalistic approach influenced by broader Italian trends. While his style might be characterized by a certain restraint compared to the more exuberant Baroque of Rome, its elegance, sincerity, and technical mastery resonated deeply within the Florentine cultural milieu. Through his own extensive body of work and the many pupils he trained, Matteo Rosselli left an indelible mark on the art of seventeenth-century Florence, ensuring his place as a respected and significant master in the annals of Italian art history.