Francesco Curradi, a prominent figure in the Florentine art scene of the late 16th and early 17th centuries, stands as a testament to the enduring power of religious art during a period of significant stylistic evolution. Born in Florence in 1570 and passing away in the same city in 1661, Curradi's long and productive career spanned the transition from the lingering echoes of late Mannerism to the burgeoning dynamism of the Baroque. He carved a niche for himself as a master of devotional painting, imbuing his works with a profound sense of piety, elegant draughtsmanship, and a subtle emotional intensity that resonated deeply with the spiritual aspirations of his time. His contributions, though perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his Roman contemporaries, were crucial to the fabric of Florentine Seicento painting, influencing a generation of artists and leaving an indelible mark on the city's sacred spaces.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Francesco Curradi's artistic journey began within a family already steeped in creative pursuits. His father, Tadeo Curradi, was a sculptor, providing young Francesco with an early immersion in the world of art. This familial connection to the visual arts likely fostered his innate talents and guided his initial steps towards a painterly career. Florence, at this time, was a city rich in artistic heritage, still basking in the afterglow of the High Renaissance masters like Michelangelo and Raphael, yet also grappling with the more stylized and intellectually complex forms of Mannerism.

A pivotal moment in Curradi's development came when he entered the workshop of Giovanni Battista Naldini (c. 1535–c. 1591). Naldini was a significant late Mannerist painter in Florence, himself a pupil of Pontormo, and a prolific artist known for his elongated figures, sophisticated compositions, and often cool, refined color palettes. Under Naldini's tutelage, Curradi would have absorbed the tenets of Florentine disegno – the emphasis on drawing and intellectual structure as the foundation of art. This training instilled in him a strong command of line and form, which would remain a hallmark of his style even as it evolved.

In 1590, at the age of twenty, Curradi took a significant step in formalizing his artistic standing by enrolling in the prestigious Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence. This institution, founded by Giorgio Vasari under the patronage of Cosimo I de' Medici, was a vital center for artistic education and discourse, aiming to elevate the status of artists and promote excellence in the arts. Membership in the Accademia signified a recognized level of skill and professionalism, and it provided Curradi with a platform for further development and interaction with his peers. His early experiences, therefore, were deeply rooted in the Florentine tradition, shaped by a sculptor father, a prominent Mannerist master, and the academic environment of the city's leading art institution.

The Evolution of Curradi's Artistic Style: From Mannerism to a Devotional Baroque

Francesco Curradi's artistic style is a fascinating blend of inherited traditions and contemporary innovations. His early works inevitably show the influence of his master, Naldini, and the prevailing late Mannerist aesthetic. This is evident in the careful draughtsmanship, the elegant, sometimes attenuated figures, and a certain refined grace. However, Curradi's art did not remain static. As the 17th century dawned, new artistic currents, collectively known as the Baroque, began to sweep across Italy, originating primarily in Rome with artists like Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci.

While Florence's response to the Baroque was perhaps more measured and conservative than Rome's, Curradi's work demonstrates a clear engagement with its principles. He gradually moved towards a style characterized by greater naturalism, a more direct emotional appeal, and a softer, more nuanced use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). His figures, while retaining their elegance, gained a greater sense of volume and presence. The compositions, though often maintaining a classical balance, could incorporate more dynamic elements and a heightened sense of drama, particularly in narrative scenes.

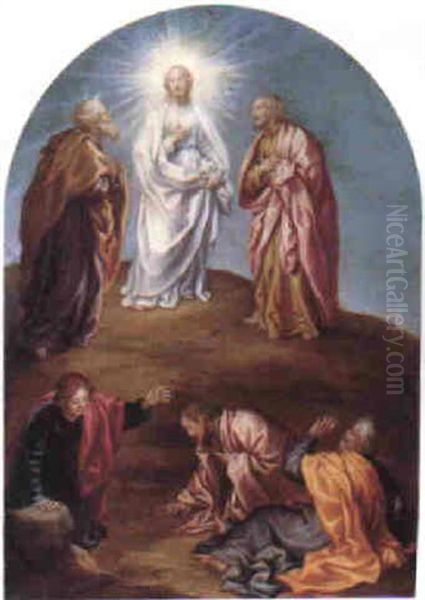

A key characteristic of Curradi's mature style is its profound devotional quality. He excelled in portraying religious subjects with a sincere piety and a gentle melancholy that invited contemplation. This was in keeping with the Counter-Reformation's emphasis on art that could inspire faith and devotion among the laity. Curradi's approach was less about overt theatricality and more about an internalized, heartfelt spirituality. His use of color often involved rich, warm tones, and he was particularly noted for his skill in drawing, especially with red chalk, which lent a softness and vibrancy to his preparatory studies and, by extension, to his finished paintings. This "chalky" feel, combined with a unique glossy treatment in some of his works, contributed to their distinctive visual appeal. He masterfully fused the clarity and linear precision of the Florentine tradition with the emergent emotional depth and visual richness of the Baroque.

Major Themes and Ecclesiastical Patronage

The vast majority of Francesco Curradi's oeuvre is dedicated to religious themes, a reflection of the primary sources of artistic patronage in 17th-century Florence and, indeed, across Catholic Europe. The Counter-Reformation, the Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation, placed great emphasis on the role of art as a tool for teaching, inspiring, and reaffirming faith. Curradi became a favored artist for ecclesiastical commissions, producing numerous altarpieces, devotional paintings for private chapels, and larger narrative cycles for churches and monastic orders throughout Florence and the wider Tuscan region.

His subjects frequently included scenes from the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and various saints. Madonnas, Crucifixions, and depictions of saints in moments of ecstasy, martyrdom, or performing miracles were common. Curradi had a particular sensitivity for portraying the Virgin Mary, often imbuing her with a tender grace and sorrowful dignity. His depictions of saints, such as Saint Francis Xavier or Saint Lawrence, emphasized their piety and spiritual fortitude.

One of the significant patrons for whom Curradi worked was the Carmelite order, particularly for the church and convent of Santa Maria Maddalena de' Pazzi in Florence. Saint Mary Magdalene de' Pazzi was a Carmelite mystic canonized in 1669, but her cult was already strong in Florence during Curradi's lifetime. His works for this complex, including a series of red chalk drawings illustrating her life, demonstrate his ability to translate complex spiritual experiences into compelling visual narratives. His involvement with such prominent religious orders underscores his reputation as an artist capable of fulfilling the specific devotional and theological requirements of his patrons. He also undertook decorative projects, such as frescoes for the Casa Buonarroti, the house museum dedicated to Michelangelo, indicating his versatility and respected position within the Florentine artistic community.

A Survey of Key Works and Their Significance

Francesco Curradi's extensive body of work is preserved in numerous churches, convents, and museums, primarily in Italy. Several key pieces highlight his stylistic development and thematic concerns.

An early example, the Madonna and Child (Madonna e Bambino) painted in 1597 for the Volterra Cathedral, already shows his elegant figural style and gentle devotional tone. This was soon followed by the Birth of the Virgin Mary (Nascita di Santa Maria) in 1598, also for the Volterra Cathedral, a narrative work that would have allowed him to demonstrate his compositional skills.

Works like the Crucifixion (Croce) from 1600 and the Madonna and Saints (Madonna e Santi) from 1602, both located in Legnaia (a suburb of Florence), further established his reputation. These pieces likely showcased his evolving ability to convey pathos and spiritual solemnity.

A significant work that found its way to a major international collection is Saint Lawrence (San Lorenzo), painted around 1608 and now housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris. The depiction of the martyred saint would have provided ample opportunity for Curradi to explore themes of faith and suffering, characteristic of Baroque religious art.

One of his most important and complex commissions was St. Francis Xavier Preaching to the Representatives of the Four Continents, completed in 1622 for the church of San Giovannino degli Scolopi in Florence. This large-scale altarpiece is a dynamic composition, reflecting the global missionary zeal of the Jesuit order and showcasing Curradi's ability to manage multiple figures and create a compelling narrative scene. It demonstrates a clear Baroque sensibility in its expansive scope and persuasive rhetoric.

Later in his career, Curradi continued to produce significant altarpieces. The Madonna in Glory (Madonna in Gloria), painted around 1650 for the Badia Fiorentina (the ancient Benedictine abbey in Florence), shows his sustained mastery and the enduring appeal of his devotional style even in his advanced years.

Beyond these large-scale paintings, Curradi was a prolific draftsman. The Uffizi Gallery in Florence holds a significant collection of his drawings, which reveal his meticulous preparatory process and his skill with chalk and ink. The aforementioned series of 87 red chalk drawings depicting the life of Saint Mary Magdalene de' Pazzi, preserved in the archives of the Carmelite convent, are particularly noteworthy for their narrative clarity and delicate execution. He also created a Last Judgment for the Church of San Giovanni Decollato (St. John the Beheaded) in Florence, a theme demanding grand scale and dramatic intensity. Another notable work is St. Mary Magdalene Receiving the Veil, painted for Santa Maria Maddalena de' Pazzi, further cementing his connection with this important Florentine saint and her order.

Contemporaries, Influences, and Students: Curradi in the Florentine Art World

Francesco Curradi did not operate in an artistic vacuum. He was part of a vibrant, if somewhat conservative, Florentine art world. His primary influence, as noted, was his teacher, Giovanni Battista Naldini, who grounded him in the late Mannerist tradition. However, Curradi was also receptive to other artistic currents. He would have been aware of the reformist tendencies in Florentine painting, spearheaded by artists like Santi di Tito (1536-1603), who sought a greater clarity and naturalism in religious art, moving away from the more artificial aspects of high Mannerism. Ludovico Cardi, known as Cigoli (1559-1613), was another key figure in this transition, introducing a warmer, more Venetian-influenced color palette and a more emotive style that prefigured the Baroque. Gregorio Paganini (1558-1605), with whom Curradi is sometimes stylistically compared, also played a role in this shift.

Among his direct contemporaries in Florence were painters such as Jacopo Chimenti, known as Jacopo da Empoli (c. 1551–1640), Matteo Rosselli (1578–1650), and Domenico Cresti, known as Passignano (1559–1638). These artists, along with Curradi, formed the core of Florentine painting in the early Seicento. While each had his individual style, they often shared commissions and contributed to a distinctively Florentine brand of Baroque art, characterized by its continued emphasis on disegno, its devotional sincerity, and a certain restraint compared to the more exuberant Baroque of Rome or Naples. Cristofano Allori (1577-1621), known for his famous Judith with the Head of Holofernes, was another important contemporary whose work displayed a rich colorism and dramatic intensity.

Curradi also played a role in shaping the next generation of Florentine painters through his workshop. Among his known pupils were Cesare Dandini (1596–1657), who developed a highly refined and elegant style, often with a touch of theatricality, and Jacopo Vignali (1592–1664), who became a prolific painter of religious and mythological subjects. Other students included Cosimo Duti and Cosimo Gamberucci. Through these students, Curradi's influence extended further into the 17th century, helping to perpetuate the particular character of Florentine painting. His interactions, collaborations, and teaching activities placed him firmly within the network of artistic exchange that defined the period.

Later Career, Recognition, and Anecdotes

Francesco Curradi enjoyed a long and respected career, remaining active well into his later years. His dedication to religious art and his consistent quality earned him significant recognition. A notable honor came in 1627 when Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini, himself a Florentine) conferred upon him a knighthood, likely the Order of Christ or a similar papal honor. This was in recognition of his artistic achievements, possibly for a specific work such as a portrait of St. Thomas, and it signified his esteemed status not only in Florence but also in the eyes of the highest ecclesiastical authority. Such an honor was a mark of considerable prestige for an artist.

Anecdotes from his life further illuminate his character and career. His involvement with the Casa Buonarroti, working on frescoes, suggests a connection to the legacy of Michelangelo, a revered figure in Florence. This project, undertaken for Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger (grand-nephew of the master), aimed to celebrate the family's lineage and artistic heritage. Curradi's participation indicates his standing as a trusted and skilled artist capable of contributing to such a prestigious and historically significant undertaking.

His family background, with his father Tadeo being a sculptor, undoubtedly provided a supportive environment for his artistic inclinations. This familial immersion in the arts was not uncommon and often laid the groundwork for successful careers. Curradi's own role as a teacher to artists like Cesare Dandini shows him passing on this artistic lineage.

The story of his extensive series of red chalk drawings for the life of Saint Mary Magdalene de' Pazzi highlights his dedication to specific commissions and his mastery of drawing as a narrative tool. These drawings, intended perhaps as preparatory studies for unexecuted paintings or as a devotional series in their own right, speak to his deep engagement with the spiritual lives of the saints he depicted. His continued productivity into old age underscores his commitment to his craft and the sustained demand for his particular brand of devotional art.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Francesco Curradi's legacy is primarily that of a key figure in the Florentine Seicento, an artist who successfully navigated the transition from late Mannerism to the Baroque while maintaining a distinctively Florentine character in his work. He was not a radical innovator in the vein of Caravaggio, but rather a master of synthesis, blending the Florentine emphasis on disegno and graceful composition with the new Baroque sensibility for emotional depth and naturalism.

His most significant contribution lies in the realm of religious art. In an era defined by the Counter-Reformation, Curradi provided a visual language that was both doctrinally sound and emotionally resonant. His paintings, characterized by their sincere piety, gentle melancholy, and elegant figures, served the devotional needs of his patrons and the wider public. He helped to define a particular strand of Florentine Baroque that was more restrained, introspective, and focused on clarity of narrative and emotional sincerity than the more flamboyant styles found elsewhere in Italy.

Through his numerous altarpieces and devotional works, he left a lasting imprint on the sacred spaces of Florence and Tuscany. Many of his paintings remain in situ or in local museums, continuing to inspire and instruct. His influence also extended through his students, notably Cesare Dandini and Jacopo Vignali, who carried forward aspects of his style and approach into the mid-17th century.

While perhaps overshadowed in broader art historical narratives by more revolutionary figures, Francesco Curradi's importance to the specific context of Florentine art is undeniable. He was a prolific, skilled, and highly respected painter who embodied the artistic and spiritual values of his time and place, contributing significantly to the rich tapestry of Italian Baroque art. His works remain a testament to the enduring power of devotional painting and the unique artistic identity of Florence during the Seicento.

Conclusion

Francesco Curradi emerges from the annals of art history as a dedicated and skilled Florentine painter whose career bridged two significant artistic epochs. From his grounding in the late Mannerist traditions under Giovanni Battista Naldini to his mature embrace of a nuanced, devotional Baroque style, Curradi consistently produced works of high quality and profound spiritual resonance. His art, predominantly religious in theme, catered to the needs of the Counter-Reformation Church and the pious sensibilities of his Florentine patrons. With a keen eye for elegant composition, a masterful command of drawing, and an ability to convey subtle emotional states, he created a body of work that adorned numerous churches and private collections. Honored by popes and respected by his peers, Curradi also played a role in educating the next generation of artists. His legacy is that of a quintessential Florentine master of the Seicento, whose paintings continue to speak of a deep faith and an unwavering commitment to the expressive power of art.