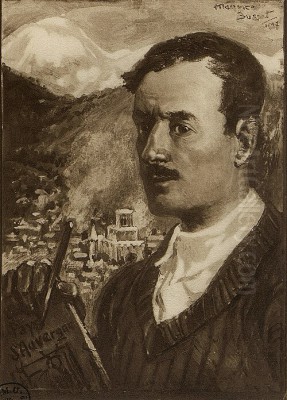

Maurice Busset (1879-1936) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in early 20th-century French art. A painter and a master of the woodcut, his career was profoundly shaped by the tumultuous events of his time, particularly the First World War. His body of work offers a compelling visual chronicle, transitioning from the stark realities of conflict to the serene landscapes of his homeland, and delving into the technical intricacies of printmaking. This exploration of Busset's life and art will illuminate his contributions, situate him within the artistic currents of his era, and acknowledge his lasting, though perhaps quiet, influence.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in France in 1879, Maurice Busset came of age during a period of immense artistic ferment. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw Paris as the undisputed capital of the art world, a crucible where Impressionism had given way to Post-Impressionism, and new movements like Fauvism and Cubism were beginning to challenge established conventions. While specific details of Busset's early artistic training are not extensively documented in the provided information, it is clear that he was actively engaged in creative pursuits from a relatively young age. A sketch titled “C$MESSE DOME” dated March 20, 1909, indicates his early productivity and immersion in the artistic practices of the time.

This period in France was rich with inspiration. Artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir were elder statesmen, their Impressionist legacy still vibrant. The Post-Impressionists, including Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh (though deceased, his influence was growing), and Paul Gauguin, had opened new pathways for expressive color and form. Younger artists, such as Henri Matisse and André Derain, were making waves with the bold, non-naturalistic colors of Fauvism around 1905. Simultaneously, Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso were on the cusp of developing Cubism. Busset would have been surrounded by these revolutionary changes, which undoubtedly informed his own developing visual language.

The Crucible of War: Documenting Conflict

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 irrevocably altered the European landscape, and its impact on artists was profound. Many, like Busset, were compelled to document their experiences, whether as official war artists, soldiers, or civilian observers. Busset’s work from this period is particularly notable for its patriotic fervor and its focus on the emerging role of aviation in warfare. He was not merely an observer; he identified with the conflict, even signing some works with the moniker "aviateur" (aviator), suggesting a deep personal connection or perhaps even direct involvement with the air services.

His 1912 painting, Port militaire à Cayeux, created just before the war's full eruption, already hinted at an interest in military subjects and coastal defenses. This thematic concern would intensify dramatically with the onset of hostilities. Busset’s art became a conduit for expressing the national sentiment and the dramatic, often terrifying, realities of modern warfare. He did not shy away from the destructive power of new technologies, a theme that resonated with other artists across Europe, such as C.R.W. Nevinson in Britain, whose Futurist-inspired works captured the dynamism and mechanization of war, or Fernand Léger, whose experiences at the front transformed his art towards a more "Tubist" style reflecting the metallic, fragmented nature of modern conflict.

One of Busset’s most powerful paintings from this era is Bombardement de Ludwigshafen (1918). This work depicts the Allied bombing of the German industrial city, a strategic target. Busset renders the scene with a dramatic intensity, focusing on the explosions, smoke, and the chaos of the aerial assault. His use of color and dynamic composition conveys the violence and destructive force of the bombardment, reflecting a strong patriotic sentiment from the French perspective. The painting serves as both a historical document and an emotional testament to the realities of aerial warfare, a relatively new and terrifying aspect of the Great War.

Beyond grand paintings, Busset also utilized the medium of woodcut to disseminate images of the war. He created a series of woodcuts depicting the German bombing of Paris in 1918. These prints often focused on the civilian experience, such as Parisians seeking shelter in Métro stations during nighttime raids. One interesting anecdote surrounding these works involves a contemporary query about whether the depicted citizens would have used flashlights, a technology that was becoming increasingly available. This small detail highlights the prints' role in capturing the lived reality of wartime Paris, down to the technological nuances of the period. These woodcuts, with their stark contrasts and expressive lines, share a certain graphic power with the war-themed prints of artists like Félix Vallotton, whose own woodcuts often conveyed a grim, unromanticized view of conflict.

His interest in aviation was further evidenced in works like Hydravion sur l'étang de Cazaux (1917) and the later collection Nos Escadrilles pendant la Grande Guerre (Our Squadrons during the Great War, 1918). These pieces underscore his fascination with the new dimension of warfare and the machines that dominated it. This focus on aviation was shared by other artists, like the British printmaker Howard Leigh, who also created works themed around aircraft. Busset's depictions aimed to capture the thrill and danger associated with early military flight, contributing to a visual culture that was grappling with rapid technological advancement amidst global conflict.

Master of the Woodcut: Technique and Expression

Maurice Busset was not only a painter but also a dedicated practitioner and theorist of the woodcut. His commitment to this medium is exemplified by his publication, La technique Moderne du Bois Grave (The Modern Technique of Wood Engraving/Woodcut). This book, illustrated with his own prints, served as a guide to the processes and artistic possibilities of woodcut, a medium that had undergone a significant revival in Europe since the late 19th century, partly inspired by Japanese Ukiyo-e prints and the Arts and Crafts movement.

Busset's woodcuts in La technique Moderne du Bois Grave often depicted the very act of creation: an artist at a workbench carving a block, or two workers engaged in the process. These images demystified the technique while celebrating its craft. The inherent qualities of the woodcut – strong contrasts, bold lines, and a certain rustic directness – lent themselves well to Busset's expressive style. His subjects in this medium were diverse, ranging from the aforementioned war scenes, including a series on French cavalry during WWI, to more tranquil depictions of landscapes and rural life.

The revival of the woodcut in the early 20th century involved artists who appreciated its potential for direct expression and its democratic nature, allowing for multiple originals. Artists like Edvard Munch had already demonstrated the profound emotional power of the woodcut, while in France, figures such as Paul Gauguin and later Henri Matisse and André Derain experimented with the medium. Busset’s contribution was both practical, through his instructional book, and artistic, through his own accomplished prints. He understood how to exploit the grain of the wood and the cutting tools to achieve varied textures and dynamic compositions, conveying emotion through the stark interplay of black and white or through the careful application of color in multi-block prints.

His woodcuts of the German bombing of Paris, for instance, used the medium's inherent drama to heighten the tension and fear of the civilian experience. The deep blacks of the night sky or the shadowed interiors of the Métro stations would have been particularly effective in conveying the oppressive atmosphere of the raids. Similarly, his depictions of cavalry would have benefited from the woodcut's ability to capture strong, decisive movement and form.

Beyond the Battlefield: Landscapes and Rural Life

While the First World War was a defining period for Maurice Busset, his artistic vision extended beyond the depiction of conflict. He was also a keen observer of the French landscape and rural life, themes that allowed for a different kind of expression, often more contemplative and serene. His work Port militaire à Cayeux (1912), though hinting at military presence, is primarily a coastal landscape, capturing the atmosphere of the port.

Later in his career, Busset continued to explore landscape and genre scenes. A work titled Au Marché (At the Market), dating from around 1920, suggests a shift towards depicting everyday life in peacetime. Such scenes were a staple for many artists of the period, offering a connection to traditional ways of life and the enduring beauty of the French countryside. These works likely reflected a desire, common in the post-war era, to return to themes of stability and cultural continuity.

His paintings and prints of the Auvergne region, such as those featured in a collection or book possibly titled Vieux pays d'Auvergne (Old Auvergne Country), demonstrate his deep appreciation for the specific character of this part of France. These works would have focused on the unique topography, architecture, and perhaps the traditional customs of Auvergne. In these pieces, Busset's "sensitive and expressive" style, noted for its ability to convey strong emotions through "color, rhythm, and texture," would have found ample opportunity for expression. He could capture the ruggedness of the volcanic landscape, the warmth of the local stone, or the quiet dignity of rural labor.

This engagement with landscape and regional identity connects Busset to a long tradition in French art, from the Barbizon School painters like Jean-François Millet to Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne with his intense focus on Mont Sainte-Victoire, or Paul Signac whose pointillist technique beautifully captured the light and color of French coastal towns. Busset’s approach, while distinct, shared this commitment to finding artistic meaning in the local and the familiar.

A Foray into History: The Gergovia Study

Beyond his artistic endeavors, Maurice Busset also possessed a keen interest in history, culminating in the publication of his book Gergovia, capitale des Gaules et l'Oppidum du plateau des Côtes (Gergovia, Capital of the Gauls and the Oppidum of the Plateau des Côtes) in 1933. This scholarly work focused on the ancient Gallic stronghold of Gergovia, famous as the site of Julius Caesar's defeat at the hands of Vercingetorix in 52 BC.

Busset's research explored the strategic importance of Gergovia, located near modern-day Clermont-Ferrand in his beloved Auvergne region, and its role as a major center of Gallic resistance. The book delved into the archaeology and topography of the site, analyzing the oppidum (a fortified settlement) on the Plateau des Côtes. This publication demonstrates a different facet of Busset's intellect and his deep connection to the history and heritage of France, particularly of the Auvergne region.

This historical work, while distinct from his art, can be seen as complementary. Both his art and his historical writing stemmed from a profound engagement with French identity, whether expressed through the depiction of contemporary struggles and landscapes or through the scholarly investigation of its ancient past. His meticulous approach to understanding Gergovia likely mirrored the careful observation and technical skill he brought to his painting and printmaking.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Lasting Impressions

Maurice Busset's artistic style is characterized by its sensitivity and expressiveness. He possessed a talent for conveying emotion and atmosphere, whether in the dramatic intensity of a battle scene or the quiet charm of a rural landscape. His handling of color, rhythm, and texture was central to this expressive power. In his paintings, one can imagine a vibrant palette used to capture the flash of explosions or the subtle hues of the French countryside. His compositions, particularly in his war art, were often dynamic, guiding the viewer's eye through scenes of action and turmoil.

In his woodcuts, Busset demonstrated a mastery of line and contrast. He understood how to simplify forms to their essential elements, creating powerful graphic statements. His book, La technique Moderne du Bois Grave, attests to his technical proficiency and his desire to share this knowledge, contributing to the ongoing vitality of the printmaking arts in France. The directness and inherent strength of the woodcut medium were well-suited to his subjects, particularly the stark realities of war and the robust character of rural scenes.

The influence of Maurice Busset on subsequent art may not be as widely trumpeted as that of some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, but it is nonetheless significant. His war art contributed to a body of work by numerous artists who sought to make sense of an unprecedented global conflict. These images served as historical records, propaganda, and personal testaments, shaping public perception and memory of the war. Artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz in Germany, for example, would later produce searing indictments of war, though from a vastly different, more critical and traumatized perspective. Busset’s patriotic depictions offered one important contemporary viewpoint.

His dedication to the woodcut also played a role in maintaining the relevance and promoting the techniques of this historic medium. By both practicing and teaching through his book, he helped ensure that the skills and artistic possibilities of woodcut were passed on and appreciated. The early 20th century saw a flourishing of printmaking, with artists like Käthe Kollwitz in Germany using prints for powerful social and political commentary, and the artists of Die Brücke (The Bridge) group, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, revitalizing the woodcut with raw, expressive energy. Busset was part of this broader international resurgence.

Busset in the Public Eye: Anecdotes, Collections, and the Market

While not a household name on the scale of Picasso or Matisse, Maurice Busset's works have maintained a presence in collections and on the art market. His pieces appear in auction records, indicating a continued interest among collectors. For instance, his painting Au Marché (c. 1920) was listed with an estimate of €400-€800 at Artprecium, while Nos Escadrilles pendant la Grande Guerre (1918) from the same auction house had an estimate of €200-€400. A collection of 15 aviation-themed prints, En Avion Vois Et Combats (1914-1918), was estimated at £150-£250. These figures suggest that his works, particularly those related to WWI and aviation, are accessible to collectors of historical and military art.

His works are also noted in catalogues, such as that of the Librairie ancienne Clagahé Lyon, though specific institutional collections are not detailed in the provided information. It is likely that museums with collections focusing on French art of the early 20th century, military history, or the history of printmaking would hold examples of his work. The Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace (French Air and Space Museum) in Le Bourget, Paris, for instance, might be a logical repository for his aviation-themed pieces, given his clear interest and the "aviateur" signature on some works.

An intriguing, though brief, mention of Busset appears in a literary context, where he is described as a young character wearing a silk shawl in a scene with someone attempting to hide. Without further context, it's difficult to ascertain the nature of this literary work or the significance of his portrayal, but it suggests that his persona or name resonated enough to be incorporated into fiction, adding another layer to his public or cultural presence.

The anecdote about the query regarding flashlights in his Paris bombing woodcuts further illustrates how his art engaged with contemporary realities and sparked discussion. It underscores the role of his prints as visual documents that captured specific moments in time, prompting viewers to consider the details of the depicted scenes.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

To fully appreciate Maurice Busset, it's essential to view him within the rich artistic milieu of his time. He was a contemporary of artists who were pushing the boundaries of visual expression in myriad ways. While Busset's style might be seen as more traditional compared to the avant-garde movements, he was undoubtedly aware of and responding to the artistic climate.

His war art can be compared and contrasted with that of Henri Yalinski, whose work Expression des Déracinés (1917), now in the collection of La contemporaine (formerly BDIC) in Nanterre, also addressed the themes of displacement and the impact of war. Both artists sought to convey the human and societal consequences of the conflict. The starkness of Busset's woodcuts also finds parallels in the graphic work of Théophile Steinlen, known for his social realist illustrations and posters, or even the more stylized theatrical posters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, though their subject matter differed.

In the realm of printmaking, the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e, which had so profoundly affected late 19th-century artists like Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas, continued to inform the woodcut revival. Artists like Henri Rivière were known for their sophisticated color woodcuts inspired by Japanese techniques, creating a different aesthetic from Busset's often bolder, more European style, but part of the same renewed interest in the medium.

Busset's landscapes and depictions of rural life connect him to a lineage of French artists dedicated to capturing their native land. While the Impressionists had revolutionized landscape painting, later artists continued to find inspiration in the French countryside. Albert Marquet, a friend of Matisse and associated with Fauvism, painted many serene views of Paris, ports, and rivers, often with a subtle, tonal palette that contrasts with Busset's potentially more robust approach but shares a focus on specific locales.

The period also saw the rise of Art Nouveau, with its organic, flowing lines, and the beginnings of Art Deco, with its geometric stylization. While Busset's work doesn't appear to directly align with these decorative styles, they formed part of the visual culture he inhabited. His commitment to representation, whether of war, landscape, or the craft of printmaking, provided a counterpoint to the increasing abstraction seen in the work of artists like Robert Delaunay, whose Orphist paintings celebrated the dynamism of modern life, including early aviation, but through a prism of vibrant, fragmented color.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Legacy

Maurice Busset died in 1936, on the cusp of another world conflict. His life spanned a period of extraordinary change, both technologically and artistically. As an artist, he navigated these changes with a distinct voice, creating a body of work that reflects his deep engagement with the events, landscapes, and cultural heritage of France.

His paintings and woodcuts of the First World War, particularly those focusing on aviation and the bombing of cities, offer a valuable historical and artistic perspective on the conflict. They capture the patriotic fervor of the time, the dramatic impact of new technologies, and the experiences of those who lived through the war. His signature as an "aviateur" on some of these works adds a personal dimension, suggesting a profound connection to this aspect of the modern military.

Beyond his war art, Busset's dedication to the woodcut, exemplified by his technical manual La technique Moderne du Bois Grave and his own accomplished prints, marks him as an important contributor to the printmaking tradition. He explored a range of subjects in this medium, from the craft itself to scenes of cavalry and civilian life during wartime.

His landscapes and depictions of rural France, especially the Auvergne region, reveal a deep affection for his homeland and its traditions. These works, characterized by their sensitive use of color, rhythm, and texture, offer a more tranquil counterpoint to his dramatic war scenes. Furthermore, his scholarly work on Gergovia demonstrates an intellectual curiosity and a commitment to understanding French history that complements his artistic endeavors.

Maurice Busset may not be as widely celebrated as some of his avant-garde contemporaries, but his multifaceted career as a painter, printmaker, and historian has left a rich and varied legacy. His art provides a window into the concerns and aesthetics of early 20th-century France, chronicling a nation grappling with war, embracing its heritage, and continuing to foster a vibrant artistic culture. His works remain a testament to an artist who was both a product of his time and a keen observer of its unfolding drama.