André Victor Léon Devambez stands as a fascinating figure in French art history, an artist whose work bridged the academic traditions of the 19th century with the burgeoning modernity of the early 20th. Born in Paris on May 26, 1867, and passing away in the same city in 1943 (though some sources cite 1944), Devambez carved a unique niche for himself as a painter, illustrator, and etcher. He is particularly celebrated for his distinctive bird's-eye views of Parisian life, his humorous and imaginative illustrations, and his keen interest in the technological marvels of his age, especially aviation. His career reflects a period of immense social, cultural, and technological change, all captured through his singular artistic lens.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

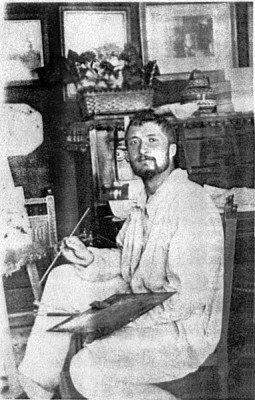

André Devambez was born into an environment steeped in art and craftsmanship. His father, Édouard Devambez, was a respected engraver and the founder of the Maison Devambez, a prominent publishing house and gallery known for its high-quality prints and deluxe editions. This familial connection provided young André with early exposure to the art world and likely fostered his innate talents. His mother, Catherine Veret (according to some sources), further contributed to a cultured upbringing. Growing up amidst the activities of the publishing house, he was surrounded by artists, writers, and the processes of image creation.

His formal artistic education began in earnest at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris during the 1880s. Here, he studied under influential academic painters such as Gustave Boulanger and Jules Lefebvre. These masters, known for their adherence to classical principles and technical proficiency, instilled in Devambez a strong foundation in drawing and composition. He also received instruction from Benjamin Constant, another leading figure in the academic art establishment of the time. This rigorous training shaped his technical abilities, even as his thematic interests would later diverge towards more contemporary subjects.

Devambez quickly proved his talent. A pivotal moment in his early career came in 1890 when he was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome for painting. This highly coveted prize granted him a residency at the French Academy in Rome, housed in the Villa Medici. This period allowed him to immerse himself in the masterpieces of Italian art and further hone his skills away from the immediate pressures of the Parisian art scene. His success in this competition marked him as a significant emerging talent within the French academic system.

The Parisian Panorama: A Bird's-Eye View

Upon his return to Paris, Devambez began to develop one of the most characteristic aspects of his oeuvre: his fascination with elevated viewpoints. He became known as the "painter of the sixth floor," frequently depicting the bustling streets, boulevards, and public spaces of Paris as seen from above. This unusual perspective offered a novel way to capture the energy and complexity of modern urban life, transforming crowded scenes into dynamic patterns of movement and color.

These high-angle views were likely influenced by several contemporary developments. The rapid urbanization of Paris under Haussmann had created new vistas and taller buildings, offering literal new perspectives. Furthermore, the advent of photography, particularly aerial photography which was in its infancy, provided new ways of seeing the world. Early cinema, with its experiments in camera angles and movement, may also have played a role in shaping his visual imagination. Devambez's paintings often feel cinematic, capturing fleeting moments within the grand spectacle of the city.

Works like La Charge (The Charge, depicting a crowd surge, possibly involving police, held at the Musée d'Orsay) exemplify this approach. From his high vantage point, individual figures often become part of a larger, almost abstract composition, yet Devambez retains a keen eye for anecdotal detail and human interaction within the crowd. He captured the flow of traffic, the congregation of people in squares, parades, and the general hubbub of the metropolis with a unique blend of detachment and engagement. This perspective allowed him to comment on mass society and the individual's place within it.

Illustrator and Humorist

Beyond his paintings of Paris, Devambez enjoyed a successful career as an illustrator, bringing his characteristic wit and keen observational skills to a different medium. He contributed drawings to popular illustrated magazines of the era, such as L'Illustration and Le Figaro Illustré, capturing contemporary life and events for a wide audience. His style was well-suited to narrative, often incorporating a gentle or sometimes pointed humor.

He gained particular renown for his illustrations for children's books. His work for a version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Blanche-Neige et les sept nains), created around 1902, is held by the Musée d'Orsay and showcases his ability to blend fairytale elements with his distinctive style. He published his own book, Auguste a mauvais caractère (Auguste Has a Bad Temper) in 1913, telling the story of a difficult boy through his expressive and humorous drawings. These works demonstrate his versatility and his appeal across different audiences.

Devambez also turned his hand to illustrating literary classics, such as Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels. In these illustrations, his penchant for unusual perspectives and slightly caricatured figures found fertile ground. His humor often stemmed from visual exaggeration or the juxtaposition of the mundane with the fantastic, a quality evident in both his illustrations and some of his paintings. This aspect of his work connects him to a broader tradition of French caricature and graphic satire, practiced by contemporaries like Théophile Steinlen and Jean-Louis Forain.

Embracing Modernity: Aviation and Technology

Devambez lived through a period of breathtaking technological advancement, and he embraced these changes with artistic curiosity. He was particularly captivated by the dawn of aviation. The early airplanes, fragile contraptions defying gravity, captured his imagination, symbolizing human ingenuity and the conquest of new frontiers. He produced numerous works depicting airplanes, airships, and the experience of flight, becoming one of the earliest artists to seriously engage with this theme.

His painting Le seul oiseau qui vole au dessus des nuages (The Only Bird that Flies Above the Clouds, 1910) is a prime example. It poetically captures the wonder and isolation of early flight, placing the aircraft in a vast expanse of sky and clouds. This work, and others like it, position Devambez as a pioneer of aviation art. He wasn't just documenting these new machines; he was exploring their aesthetic and symbolic potential, conveying the sense of adventure and the altered perspective they offered.

His interest extended to other modern technologies as well. He created illustrations featuring early automobiles, another symbol of the rapidly changing pace of life in the early 20th century. This engagement with contemporary technology distinguishes him from many academic artists of his generation and aligns him more closely with artists interested in capturing the dynamism of modern existence, even if his style remained largely representational.

Witness to Conflict: The War Years

The outbreak of World War I profoundly impacted Devambez, as it did countless others of his generation. Despite being in his late forties, he volunteered for service in the French army in 1914, serving near Dunkirk. His patriotism led him to contribute his artistic skills to the war effort, becoming an official war artist. He documented life at the front and the realities of modern warfare through his drawings and etchings.

In 1915, during the fighting near Amiens, Devambez was severely wounded. The injury resulted in a permanent physical disability, but it did not halt his artistic output. His wartime experiences fueled a significant body of work. He produced a series of etchings titled Douze eaux-fortes [La Guerre 1914–18] (Twelve Etchings [The War 1914–18]), which offered stark and moving depictions of the conflict. These works stand as powerful testimonies to the human cost of war, rendered with the same observational acuity found in his pre-war scenes, but imbued with a new gravity.

His war art provides a valuable historical and artistic record of the conflict, capturing not just the machinery of war but also the experiences of the soldiers. Like other artists commissioned or inspired by the war, such as Christopher R. W. Nevinson in Britain or Félix Vallotton in Switzerland, Devambez translated the unprecedented scale and nature of the Great War into visual form, contributing to the complex artistic legacy of the period.

Artistic Style and Influences

André Devambez's artistic style is not easily categorized within the major movements of his time. He was trained in the academic tradition, and a high level of technical skill underpins all his work. However, he adapted this training to thoroughly modern subjects and perspectives. While sometimes discussed in relation to Realism or Naturalism due to his focus on contemporary life, his work often incorporates elements of fantasy, humor, and caricature that set it apart. His use of high viewpoints is perhaps his most radical departure from convention.

While he was a contemporary of the later Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, his technique differs significantly. He did not adopt the broken brushwork or focus on the fleeting effects of light typical of Impressionism, although his cityscapes certainly capture atmosphere and movement. His influences seem more eclectic, drawing from his academic background, the innovations of photography and cinema, the tradition of French illustration and caricature, and his personal fascination with technology and urban spectacle. Some have noted a subtle "Baroque" tendency in the dramatic composition and occasional exaggeration found in his works.

His versatility is also noteworthy. He moved comfortably between oil painting, pastel, etching, and book illustration, adapting his approach to the specific demands of each medium. Whether depicting a crowded boulevard, illustrating a children's story, or capturing the desolation of the trenches, his work is unified by a strong graphic sensibility and a unique way of observing the world.

Contemporaries and Context

André Devambez operated within the vibrant and complex art world of Paris during the Belle Époque and the interwar years. His teachers, Jules Lefebvre and Gustave Boulanger, as well as Benjamin Constant, were central figures of the French Academic system, which still held considerable sway through institutions like the École des Beaux-Arts and the official Salon. Other prominent academic painters of the era included masters of historical and Orientalist scenes like Jean-Léon Gérôme and the highly popular William-Adolphe Bouguereau, as well as Edouard Debat-Ponsan, known for his realist scenes and historical paintings.

While distinct from Impressionism, Devambez shared with artists like Gustave Caillebotte an interest in depicting modern Parisian life and experimenting with unusual perspectives, though Caillebotte's work is more closely aligned with the Impressionist group. The meticulous chronicler of Parisian society, Jean Béraud, was another contemporary focused on similar subject matter, albeit typically from street level.

In the realm of illustration and graphic arts, Devambez's contemporaries included influential figures like Théophile Steinlen, known for his posters and depictions of Montmartre life; Jean-Louis Forain, a painter and sharp social satirist; the humorous draftsman Caran d'Ache; and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose posters and paintings captured the Parisian entertainment world. Devambez's work shares with these artists an engagement with popular media and contemporary social observation.

His interest in technology and flight connects him thematically, if not stylistically, to later movements like Futurism, which celebrated the machine age, though Devambez's approach remained rooted in representation and observation rather than abstraction or the depiction of speed itself. He stands somewhat apart, a unique observer navigating the crosscurrents of tradition and modernity.

Legacy and Recognition

During his lifetime, André Devambez achieved considerable recognition within the French art establishment. He exhibited regularly at the Salon, won the Prix de Rome, contributed to major publications, and was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour. His father's publishing house, Maison Devambez, also provided a platform for his work. The family connection continued, with his son, André Victor Edouard Devambez, reportedly taking over the business later on. (His other son, Pierre Devambez, became a noted archaeologist and curator at the Louvre).

Despite these successes, Devambez's work fell into relative obscurity for several decades after his death in 1943 or 1944. Perhaps his unique style, which didn't fit neatly into the dominant narratives of modernism focused on Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Cubism, and abstraction, contributed to this neglect. However, recent years have seen a significant resurgence of interest in his art.

A major retrospective exhibition, "André Devambez. Vertiges et facéties" (André Devambez: Vertigo and Mischief), held at the Petit Palais in Paris in 2022, brought his work to a new generation and highlighted the originality and breadth of his output. His paintings and illustrations are now appreciated for their unique perspectives, their witty and insightful observations of Parisian life, their pioneering engagement with aviation, and their poignant documentation of the Great War.

His works are held in major French museum collections, including the Musée d'Orsay, the Louvre, and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. Today, André Devambez is recognized as a significant and highly individualistic artist who captured the spirit of his transformative era with technical skill, imaginative flair, and a perspective all his own. He remains a testament to the diverse paths taken by artists responding to the dawn of the 20th century.

Conclusion

André Devambez offers a compelling case study of an artist who successfully navigated the transition from 19th-century academic training to the complexities of 20th-century modern life. His signature bird's-eye views of Paris provide an unforgettable perspective on the urban experience, while his illustrations reveal a sharp wit and a talent for narrative. His fascination with aviation places him among the first visual chroniclers of the air age, and his wartime art adds a layer of profound historical testimony to his oeuvre. Though perhaps overshadowed for a time by the giants of modernism, Devambez's unique vision, technical prowess, and thematic range secure his place as a distinctive and important voice in French art history. His work continues to engage viewers with its blend of observation, imagination, humor, and its captivating portrayal of a world in rapid transformation.