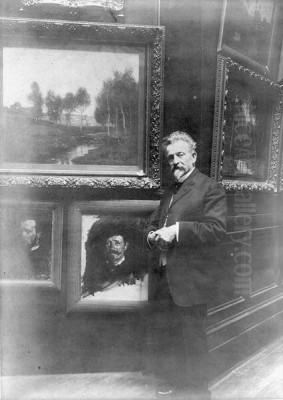

Max Weyl, an artist whose life bridged the old world and the new, carved a significant niche for himself in the annals of American art history. Born in Germany and later an immigrant to the United States, Weyl became inextricably linked with the landscape of Washington, D.C., capturing its sylvan beauty with a sensitivity and poeticism that earned him widespread admiration and the affectionate title of the "American Daubigny." His journey from a craftsman to a celebrated painter, his embrace of the Barbizon aesthetic, and his dedication to depicting the natural charm of his adopted city define his enduring legacy.

From German Roots to American Shores

Max Weyl's story begins in Mühlen-am-Neckar, near Horb, in the Kingdom of Württemberg, Germany, where he was born on December 1, 1837. His early life in Germany provided the foundational experiences that would later subtly inform his artistic perspective. Like many Europeans of his era, the promise of opportunity and a new beginning in America beckoned. In 1853, at the age of sixteen, Weyl made the transformative journey across the Atlantic, immigrating to the United States.

He initially settled in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, a common path for many German immigrants. There, he likely engaged in various trades to establish himself. His early profession was that of a watchmaker and jeweler, a craft requiring precision, patience, and an eye for detail—qualities that would later serve him well in his artistic endeavors. This period of his life, though not directly related to painting, honed a meticulousness that can be discerned in the careful construction and nuanced observations of his later artworks.

The Call of Art in the Nation's Capital

By 1861, Max Weyl had relocated to Washington, D.C., a city on the cusp of monumental change and growth, particularly in the aftermath of the Civil War. He continued his trade as a jeweler, opening a shop that provided him with a livelihood. However, the artistic currents of the city and an innate passion for visual expression began to pull him in a new direction. Washington, D.C., while not yet the art center that New York or Boston was becoming, possessed a burgeoning artistic community and, crucially, a landscape of remarkable, often understated, beauty.

Weyl was largely self-taught as a painter in his initial years. He began by painting still lifes, a traditional genre for aspiring artists to hone their skills in composition, color, and the rendering of form and texture. These early works demonstrated a competent hand and a keen observational ability. However, it was the natural world, particularly the landscapes surrounding Washington, that truly captured his artistic imagination and would become the hallmark of his career.

A pivotal figure in Weyl’s transition to a full-time artist was Charles Lanman (1819-1895), an established landscape painter, author, and government official in Washington. Lanman, known for his own depictions of American scenery and his writings on art, recognized Weyl's burgeoning talent. He encouraged Weyl to dedicate himself more fully to painting, providing validation and perhaps guidance that was crucial for an artist finding his path. This encouragement from a respected peer likely emboldened Weyl to pursue art with greater seriousness.

Embracing the Barbizon Spirit

The mid-to-late 19th century saw a significant shift in landscape painting, moving away from the grand, often idealized vistas of the Hudson River School, exemplified by artists like Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church. A more intimate, atmospheric, and subjectively emotional approach, pioneered by the French Barbizon School, was gaining traction in America. Artists of the Barbizon School, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, Jean-François Millet, and Théodore Rousseau, favored direct observation of nature, often painting en plein air or developing studio works from outdoor sketches. They sought to capture the mood, light, and transient effects of the landscape, imbuing their scenes with a quiet poetry.

Max Weyl was profoundly influenced by this movement, particularly by the works of George Inness (1825-1894), one of America's foremost landscape painters who himself had absorbed Barbizon principles. Inness's later Tonalist works, characterized by their evocative atmosphere, subtle color harmonies, and spiritual undertones, resonated deeply with Weyl. While Weyl may not have formally studied abroad in his early years, he would have encountered Barbizon and Inness's works through exhibitions, prints, and the general artistic discourse of the time.

Weyl’s style evolved to reflect these influences. He moved away from the crisp detail of earlier landscape traditions towards a softer, more suggestive rendering of form. His palette often favored muted greens, earthy browns, and hazy blues, capturing the gentle light and atmosphere of the Potomac River Valley and its environs. His brushwork became looser, more expressive, focusing on overall effect rather than minute delineation. This approach aligned him with other American artists who embraced the Barbizon aesthetic, sometimes referred to as American Barbizon or Tonalist painters, such as Alexander Helwig Wyant, Dwight William Tryon, and Henry Ward Ranger.

His affinity for the style of Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), known for his tranquil river scenes and pastoral landscapes, was so pronounced that Weyl earned the moniker "the American Daubigny" or "the Daubigny of America." This comparison highlighted his ability to capture the serene, often melancholic beauty of the local waterways and woodlands, much as Daubigny had done for the French countryside.

Washington's Verdant Chronicler: Subjects and Themes

Max Weyl’s primary artistic activity centered around Washington, D.C., and its surrounding areas. He became the preeminent painter of the local landscape, finding inexhaustible inspiration in the familiar scenes that many residents might have overlooked. His canvases frequently depicted the picturesque Rock Creek Park, a vast urban oasis whose rugged beauty, meandering creek, and dense woodlands offered a rich variety of motifs. He painted its shaded paths, sun-dappled clearings, and the gentle flow of its waters with an intimacy that revealed his deep affection for the place.

The Potomac River and its banks were another recurrent theme. Weyl captured the broad expanses of the river, its misty mornings, and the golden light of late afternoons reflecting on its surface. He was drawn to the quiet coves, the marshy areas along the Anacostia River (then known as the Eastern Branch), and the pastoral landscapes that, at the time, still characterized much of the region beyond the city's core. His paintings often evoke a sense of tranquility and solitude, inviting contemplation.

Unlike the Hudson River School painters who often sought out dramatic, sublime scenery, Weyl found beauty in the more commonplace and accessible aspects of nature. His works are rarely grandiose; instead, they possess a quiet lyricism. He was a master of capturing specific times of day and seasons—the hazy warmth of an "Indian Summer Day," the cool shadows of a "Twilight" scene, or the fresh greens of spring. Titles such as "Lovers' Lane, Rock Creek Park," "A Quiet Nook," or "On the Potomac near Washington" indicate his focus on specific, cherished locations.

While landscapes dominated his oeuvre, he did produce other works. His early still lifes have been noted, and a piece like "Woman in Courtyard," a figural scene, demonstrates his versatility, though such works are less common in his known output compared to his prolific landscape production. The primary focus remained the soul of the D.C. landscape.

Patronage, Recognition, and Artistic Community

Max Weyl's dedication to his art and his appealing, accessible style garnered him significant recognition and patronage within Washington, D.C. One of his earliest and most important patrons was Samuel H. Kauffman (1829-1906), the influential publisher of the Washington Evening Star and a key figure in the city's cultural life, notably as president of the Corcoran Gallery of Art's board of trustees. Kauffman's support was instrumental, not only through purchases of Weyl's work but also by enhancing his visibility and reputation within the city's elite circles.

Weyl's paintings became highly sought after by local collectors, including prominent citizens, politicians, and even international dignitaries. It is noted that the Brazilian ambassador was among his patrons, and his works found their way into many affluent Washington homes, including that of the Clover family (perhaps referring to Clover Adams, wife of Henry Adams, who was a prominent figure in Washington society, though her primary artistic medium was photography). This widespread local support solidified his status as the city's foremost landscape painter.

He was an active member of the Washington, D.C. artistic community. He exhibited regularly with organizations such as the Society of Washington Artists and the Washington Water Color Club. His studio became a known spot, and he was a respected figure among his peers. Between 1882 and 1889, he reportedly shared a studio or living space in Vernon Row with fellow artist Richard Norris Brooke (1847-1920), a figure painter and influential art teacher in Washington. Such arrangements were common and fostered artistic exchange and camaraderie. Other notable Washington artists of the period, whose paths Weyl likely crossed, included Edmund Clarence Messer (1842-1919), who also painted landscapes and taught at the Corcoran School of Art, and William Henry Holmes (1846-1933), a scientist, archaeologist, and accomplished artist known for his detailed watercolors and landscapes.

A significant milestone in Weyl's career was a large retrospective exhibition of his work held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1907. This honor, bestowed by the city's premier art institution, was a testament to his achievements and his standing in the art world. The Corcoran's then-director, Frederick B. McGuire, lauded Weyl not only for his artistic talent but also for his character, referring to him as a model of "artistic and social conduct" and praising his "unfailing genius." The Corcoran Gallery acquired several of his paintings for its permanent collection, further cementing his legacy.

Artistic Style and Technique in Depth

Weyl's mature style is characterized by its atmospheric quality and its focus on capturing the mood of a scene. He typically worked with oil on canvas, employing a palette that, while capable of rendering the vibrancy of autumn foliage or the brightness of a summer day, often leaned towards more subdued, tonal harmonies. His greens are often olive or grayed, his blues soft and hazy, and his browns rich and earthy. This Tonalist approach, shared with Inness and Wyant, aimed to evoke an emotional response through color and light rather than through dramatic subject matter or precise detail.

His brushwork, while not as radically loose as that of the Impressionists who were his contemporaries (like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro), was nevertheless expressive and visible. He was less concerned with a smooth, licked surface than with conveying the texture of foliage, the shimmer of water, or the softness of a cloudy sky. Forms are often suggested rather than sharply defined, particularly in the middle ground and background, contributing to the overall atmospheric effect. This technique, often described as "painterly," allowed him to capture the fleeting effects of light and weather.

Compositionally, Weyl favored balanced, harmonious arrangements. His landscapes often feature a pathway, river, or creek leading the viewer's eye into the distance, creating a sense of depth and inviting entry into the scene. Trees frequently frame the composition or act as strong vertical elements, their foliage rendered with a sensitivity to mass and light. He had a particular skill for depicting skies, whether clear, cloudy, or aglow with the light of sunrise or sunset. The sky was not merely a backdrop but an integral part of the mood and atmosphere of the painting.

While influenced by the French Barbizon painters, Weyl’s work remained distinctly American, rooted in the specific character of the Mid-Atlantic landscape. He did not simply imitate European models but adapted their principles to his own environment and artistic temperament. His paintings are less rugged than some of Théodore Rousseau's forest scenes, and perhaps less overtly melancholic than some of Corot's misty landscapes, but they share that same commitment to finding poetry in the everyday natural world.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Max Weyl continued to paint prolifically throughout his later years, remaining a beloved and respected figure in Washington, D.C. His dedication to his craft and his consistent vision ensured a steady output of landscapes that continued to find favor with collectors and the public. He witnessed significant changes in the art world, with the rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and early Modernism, but he remained largely faithful to the Barbizon-inspired Tonalist aesthetic that had defined his mature work. This steadfastness was not a sign of artistic stagnation but rather a deep commitment to a mode of expression that he had mastered and that perfectly suited his artistic aims.

Max Weyl passed away in Washington, D.C., on July 6, 1914, at the age of 76. His death was mourned by the city he had so lovingly depicted for decades. He left behind a substantial body of work that serves as a visual record of the natural beauty of the Washington area at a time before extensive urbanization transformed many of its landscapes.

Today, Max Weyl's paintings are held in the collections of numerous prestigious institutions, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Gallery of Art (through the Corcoran Collection), The White House Historical Association, the University Club of Washington D.C., and various other museums and private collections. His work continues to be appreciated for its gentle beauty, its atmospheric depth, and its historical significance as a chronicle of the Washington landscape.

His influence extended beyond his own lifetime. As a prominent local artist, he helped to foster an appreciation for landscape painting in Washington and contributed to the development of the city's artistic culture. While he may not have been a radical innovator in the mold of European avant-garde artists, his achievement lies in his sensitive and poetic interpretation of his chosen environment, and his ability to convey the subtle charms of nature to a wide audience. He stands as a key figure in the tradition of American landscape painting, particularly within the American Barbizon and Tonalist movements, and as the undisputed "Dean of Washington Landscape Painters." His art offers a timeless escape into the serene and restorative beauty of the natural world that he knew and loved so well.