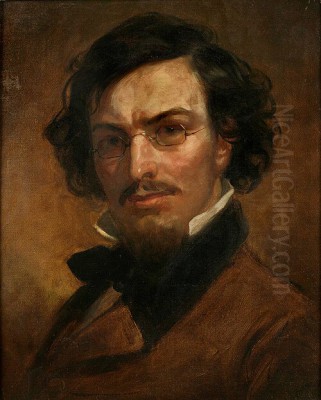

George Inness (May 1, 1825 – August 3, 1894) stands as one of the most influential and revered figures in American art history. Often hailed as the "Father of American Landscape Painting," his career spanned a pivotal period of transformation in the nation's art, moving from detailed realism towards a more subjective and spiritual interpretation of nature. Born in Newburgh, New York, and raised primarily in Newark, New Jersey, Inness forged a unique path, absorbing influences from various schools but ultimately creating a deeply personal style that explored the profound connections between the visible world and the unseen realm of emotion and spirit. His extensive body of work, comprising over a thousand paintings, watercolors, and sketches, charts a fascinating evolution, leaving an indelible mark on the course of American landscape art.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

George Inness's entry into the world of art was not straightforward. Born into a family of grocers, his early life was marked by recurring health challenges, including epilepsy, which often interrupted his formal schooling. Despite these obstacles, his artistic inclinations surfaced early. His father initially tried to steer him towards the family business, but recognizing his son's passion, eventually supported his artistic pursuits.

Inness received his first formal training not in painting, but as an apprentice map engraver in New York City around the age of 16. This experience, though brief, likely honed his sense of line and composition. However, the meticulous demands of engraving proved taxing, and he soon turned his full attention to painting. His early instruction in landscape painting came from Régis-François Gignoux, an itinerant painter who brought a European sensibility to his teaching.

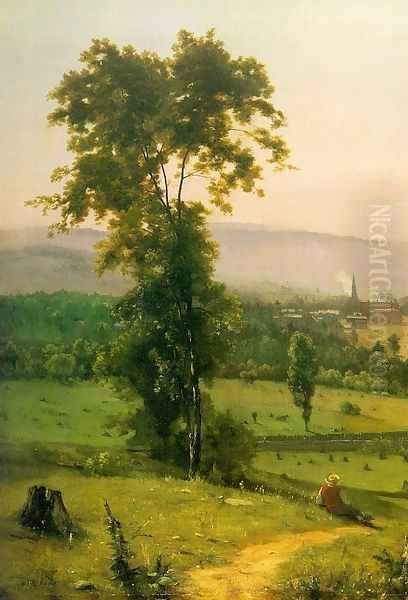

By 1844, the young Inness was ready to make his public debut. He exhibited his first painting at the National Academy of Design in New York, an institution where he would continue to show his work throughout his career. His earliest paintings aligned closely with the prevailing style of the Hudson River School, the dominant movement in American landscape painting at the time. Artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand had established a tradition of detailed, often majestic depictions of the American wilderness, celebrating its natural beauty and symbolic potential. Inness's initial works reflected this influence, characterized by careful rendering and a relatively objective approach to nature.

European Travels and Barbizon Influence

A crucial turning point in Inness's artistic development came with his travels to Europe. He made several trips abroad, with his first significant journey occurring in the early 1850s, taking him to Italy and, importantly, to France. It was in France that he encountered the works of the Barbizon School painters, a group who worked near the Forest of Fontainebleau outside Paris. Artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Charles-François Daubigny, and Jean-François Millet profoundly impacted Inness's vision.

The Barbizon painters rejected the highly finished, academic style favored at the time. Instead, they advocated for painting directly from nature (en plein air), using looser brushwork, a more subdued palette, and a focus on capturing mood, atmosphere, and the transient effects of light. They depicted intimate, pastoral scenes rather than the dramatic, panoramic vistas often favored by the Hudson River School.

Inness absorbed these lessons eagerly. He was particularly drawn to Corot's soft, atmospheric landscapes and Rousseau's textured, expressive handling of paint. This exposure encouraged him to move away from the tight, detailed style of his early work. His brushwork became freer, his compositions less structured, and his interest shifted towards capturing the overall feeling and poetic essence of a scene rather than meticulously documenting every leaf and branch. He also studied the Old Masters during his travels, drawing inspiration from the atmospheric landscapes of painters like Claude Lorrain and the dramatic compositions of Salvator Rosa, integrating their classical sense of structure with the Barbizon emphasis on mood. The dramatic skies of British painter J.M.W. Turner may also have resonated with his developing interest in atmospheric effects.

The Swedenborgian Influence

While the Barbizon School shaped Inness's technique and aesthetic, another, more philosophical influence profoundly altered the spiritual dimension of his art. Around the mid-1860s (sources vary, some citing 1863), Inness encountered the theological writings of Emanuel Swedenborg, an 18th-century Swedish scientist, philosopher, and mystic. Swedenborg's complex system of thought proposed a direct correspondence between the natural world and the spiritual realm, suggesting that every object in nature had a symbolic, spiritual meaning.

This philosophy resonated deeply with Inness's own intuitive feeling that nature was imbued with a deeper significance beyond its physical appearance. Swedenborgianism provided him with an intellectual framework for exploring the spiritual truths he sensed in the landscape. It encouraged him to look beyond mere representation and to use nature as a vehicle for expressing intangible qualities like mood, emotion, and divine presence.

This spiritual awakening marked a significant shift in his artistic goals. His landscapes became less about depicting specific places and more about evoking subjective experiences. He began to use light, color, and atmosphere not just to describe the physical world, but to suggest spiritual states and the interconnectedness of all things. His paintings increasingly aimed to capture what he termed the "civilized landscape," reflecting a harmony between nature and human presence, often imbued with a sense of divine order.

Mid-Career Development and Maturing Style

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, Inness continued to refine his style, integrating the lessons learned from the Barbizon School and his burgeoning Swedenborgian beliefs. He traveled again, spending four years in Italy from 1870 to 1874, where he painted numerous views, including scenes around the Alban Hills near Rome. His Italian landscapes often possess a lyrical quality, bathed in warm, hazy light, further developing his mastery of atmospheric effects.

During this period, his compositions became more simplified, focusing on broad masses of form and color rather than intricate detail. He experimented with different light conditions, capturing the subtle nuances of dawn, dusk, and overcast days. His palette remained relatively subdued compared to the later Impressionists, but he used color with increasing sophistication to create mood and unity.

His work from this era, while clearly distinct from the Hudson River School, also set him apart from the emerging Impressionist movement. While artists like Claude Monet were exploring the scientific analysis of light and color through broken brushwork, Inness remained focused on conveying a unified, subjective emotional response to nature, rooted in his spiritual convictions. His aim was synthesis and harmony, rather than optical analysis.

The Rise of Tonalism and Late Style

By the 1880s, Inness had entered his final and most distinctive artistic phase, becoming a leading figure in the movement known as Tonalism. Tonalism, which flourished in America between roughly 1880 and 1915, was not a formally organized school but rather a shared sensibility among artists who prioritized mood, atmosphere, and suggestion over literal description. Tonalist painters favored intimate landscapes rendered in a limited range of colors – often greens, browns, grays, and golds – creating harmonious, unified compositions.

Inness's late works are quintessential examples of Tonalism. He pushed the style towards greater abstraction and emotional intensity. Forms became increasingly blurred and simplified, melting into the surrounding atmosphere. Edges softened, and details dissolved into suggestive masses of color and light. He favored evocative times of day – twilight, dawn, moonlight – when light is diffuse and mystery pervades the landscape.

His late paintings often possess a dreamlike, introspective quality. They invite contemplation and evoke a sense of quiet spirituality. The landscapes depicted are often non-specific, serving as stages for the interplay of light, color, and mood. He sought to capture the "soul" of nature, expressing the profound emotional and spiritual connection he felt with the world around him. His residence in Montclair, New Jersey, during his later years provided ample subject matter, with the local scenery transformed through his Tonalist lens into poetic visions.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Inness's long career produced numerous masterpieces. Examining a few key works reveals the trajectory of his artistic evolution:

The Lackawanna Valley (c. 1855): An earlier work commissioned by a railroad company, this painting shows Inness grappling with the Hudson River School tradition while hinting at change. It depicts the integration of industry (the railroad) into the landscape with a degree of detail, but the softer handling of atmosphere and light foreshadows his later style. It balances documentation with a burgeoning poetic sensibility.

Peace and Plenty (1865): Painted at the end of the American Civil War, this large canvas is an allegorical landscape celebrating national reunification and agricultural abundance. While grand in scale, reminiscent of Hudson River School ambitions, the handling is softer, the light more diffused, and the mood more idyllic and harmonious than dramatic, reflecting Barbizon influences and Inness's own developing style.

The Coming Storm (c. 1878, variations exist): This iconic work exemplifies Inness's mid-career style, heavily influenced by the Barbizon School. It captures the dramatic tension just before a downpour. Dark, turbulent clouds gather overhead, while a patch of bright, almost ethereal light illuminates the middle ground. The brushwork is vigorous and expressive, conveying the dynamic forces of nature and evoking a sense of anticipation and awe. It masterfully balances realism with emotional intensity.

Sunset in the Woods (1891): A prime example of Inness's late Tonalist style. The specific details of the woods are obscured in shadow and the warm, glowing light of the setting sun. Forms are simplified and bathed in a unifying, hazy atmosphere. The painting is less about the trees themselves and more about the feeling of tranquility, mystery, and the spiritual resonance of twilight. The rich, harmonious colors and soft edges create a deeply poetic and introspective mood.

Early Morning, Tarpon Springs (1892): Painted during a trip to Florida late in his life, this work captures the unique light and atmosphere of the southern landscape. It features characteristic late-style elements: simplified composition, soft focus, and a luminous, almost mystical quality of light filtering through the trees and mist. It conveys a sense of peace and spiritual immanence.

The Home of the Heron (1893): Another late masterpiece, this painting depicts a solitary heron in a marshy landscape at twilight. The scene is enveloped in a soft, unifying haze, with subtle gradations of color creating a profound sense of stillness and mystery. It is a highly evocative work, characteristic of Inness's Tonalist approach, focusing entirely on mood and atmosphere.

Coast of Cornwall (date varies): While less frequently cited than some others, paintings depicting coastal scenes like this allowed Inness to explore the dramatic interplay of light, water, and atmosphere, likely rendered with the soft edges and evocative mood characteristic of his mature style.

Technique and Artistic Process

Inness developed a distinctive painting technique suited to his expressive goals. While his methods evolved, his later process often involved building up the painting in layers. He might start with a charcoal sketch on the canvas to establish the basic composition. He would then lay in broad areas of color, sometimes using opaque paints to define masses and capture the effects of light and texture.

A key element of his technique was the use of glazes – thin, transparent layers of paint – applied over the underlying layers. These glazes allowed him to subtly modify colors, deepen shadows, enhance luminosity, and create a sense of atmospheric depth. This layering process contributed to the rich, resonant color and unified tonality characteristic of his mature work. He was known to work intensely and intuitively, sometimes reworking canvases over long periods until he achieved the desired emotional and spiritual effect. His focus was always on the overall harmony and expressive power of the painting, rather than on superficial finish or minute detail.

Relationships, Context, and Influence

George Inness occupied a unique position within the landscape of 19th-century American art. He began his career under the shadow of the Hudson River School giants like Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, Frederic Edwin Church, John Frederick Kensett, and Albert Bierstadt. While initially influenced by their detailed realism and celebration of the American wilderness, he soon diverged, seeking a more personal and intimate approach.

His engagement with the French Barbizon School – particularly the works of Corot, Rousseau, and Daubigny – was transformative, aligning him with a more subjective and atmospheric sensibility. He became a crucial figure in transmitting Barbizon ideals to an American context, paving the way for Tonalism.

While contemporary with the French Impressionists, Inness pursued a different path. He shared their interest in light and atmosphere but rejected their emphasis on capturing fleeting moments with broken color. His goal remained the expression of enduring mood and spiritual harmony, often achieved through unified tones and blended brushwork. He stands as a bridge figure, connecting the earlier Romanticism of the Hudson River School with the later, more subjective modes of Tonalism and Symbolism.

His influence extended to the next generation of American painters, particularly those associated with Tonalism, such as Dwight Tryon, Alexander Wyant, and J. Francis Murphy. Even his son, George Inness Jr., became a painter, working in a style influenced by his father. Though his deeply personal and spiritual approach sometimes met with incomprehension or criticism during his lifetime, particularly when compared to the more literal styles then popular, his reputation grew steadily, especially towards the end of his life. A major retrospective exhibition in New York in 1889 solidified his status as a leading American artist.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

Despite suffering from epilepsy throughout his life and facing periods of financial difficulty, George Inness remained remarkably productive until his final years. He spent much of his later life in Montclair, New Jersey, which became closely associated with his work. He continued to travel, seeking new landscapes and inspiration.

His life ended fittingly, immersed in the nature he so loved to paint. While traveling in Scotland in the summer of 1894, he was watching a sunset at Bridge of Allan. Overcome by its beauty, he reportedly threw his hands into the air and exclaimed, "My God! Oh, how beautiful!" before collapsing and dying shortly thereafter.

George Inness left behind a legacy as one of America's most original and profound landscape painters. He successfully synthesized diverse influences – the realism of the Hudson River School, the atmospheric poetry of Barbizon, the spiritual depth of Swedenborgianism – into a unique and evolving artistic vision. He pushed American landscape painting beyond mere description towards subjective expression and spiritual exploration. His Tonalist masterpieces, with their evocative moods and subtle harmonies, continue to resonate with viewers, securing his place as a pivotal figure who captured not just the American land, but also the landscapes of the soul.