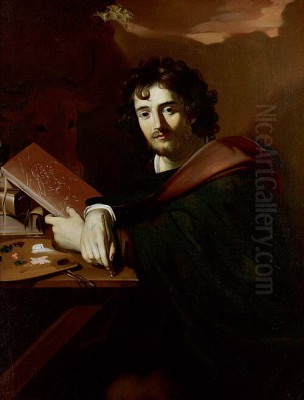

Michele Desubleo, known in Italy as Michele Fiammingo or Michele di Sobleo, stands as a fascinating example of artistic migration and stylistic synthesis in the vibrant landscape of 17th-century Italian art. Born around 1602 in Maubeuge, then part of the Spanish Netherlands (Flanders), Desubleo's career would see him traverse the major artistic centers of Italy—Rome, Bologna, Venice, and finally Parma, where he died in 1676. His oeuvre, characterized by a refined classicism deeply indebted to Guido Reni, yet infused with a Flemish sensibility for texture and a subtle emotional depth, offers a unique window into the cross-cultural currents that shaped Baroque art. Though for many years overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized Desubleo's distinct artistic personality and his contribution to the rich tapestry of Seicento painting.

Early Life and Flemish Foundations

The precise details of Michele Desubleo's earliest years and initial artistic training in Flanders remain somewhat obscure, a common challenge when reconstructing the lives of artists from this period. Maubeuge, his birthplace, was a town with its own artistic traditions, situated in a region that had produced masters like Jan Gossaert. It is widely accepted that Desubleo received his foundational artistic education in Antwerp, the bustling artistic hub of Flanders. His primary master is believed to have been Abraham Janssens (c. 1575–1632), a prominent figure in Flemish Baroque painting.

Janssens was a contemporary of Peter Paul Rubens and, like Rubens, had spent time in Italy, absorbing the lessons of both the High Renaissance masters and the burgeoning Baroque style, particularly the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio. Janssens' own work often displayed strong sculptural figures, rich colors, and a certain classical gravity, elements that would resonate in Desubleo's later development. Training under Janssens would have provided Desubleo with a solid grounding in drawing, composition, and the technical aspects of oil painting prevalent in the Flemish school, known for its meticulous detail and luminous surfaces.

Another crucial figure in Desubleo's early life was his elder half-brother, Nicolas Régnier (Niccolò Renieri, c. 1591–1667). Régnier, also a painter, had likewise trained with Janssens. The bond between the brothers was significant, as it was likely Régnier who facilitated Desubleo's eventual move to Italy. The artistic environment of Antwerp at this time was dynamic, with Rubens at the height of his fame, and artists like Anthony van Dyck and Jacob Jordaens also making their mark. This milieu would have exposed Desubleo to a high level of artistic ambition and technical skill, preparing him for the competitive artistic scene he would encounter in Italy.

The Italian Sojourn: Rome and the Circle of Guido Reni

Around 1621 or shortly thereafter, Michele Desubleo, likely accompanying Nicolas Régnier, made the pivotal journey south to Italy, the ultimate destination for ambitious Northern European artists seeking to immerse themselves in the classical tradition and the latest artistic innovations. Their first major stop was Rome, the epicenter of the art world, still pulsating with the revolutionary impact of Caravaggio and the classical reaction championed by artists like Annibale Carracci.

In Rome, Desubleo's path diverged slightly from that of Régnier, who became more closely associated with the Caravaggisti, particularly Bartolomeo Manfredi. Desubleo, on the other hand, found his way into the orbit of one of the most celebrated and influential painters of the era: Guido Reni (1575–1642). Reni, a Bolognese master who had achieved immense fame in Rome before returning to his native city, was renowned for his elegant classicism, his graceful figures, idealized beauty, and delicate, silvery palette. The opportunity to work in or be closely associated with Reni's studio was transformative for Desubleo.

The influence of Guido Reni on Desubleo's artistic development cannot be overstated. It was under Reni's sway that Desubleo refined his style, moving towards a more classical idiom characterized by balanced compositions, serene expressions, and a sophisticated handling of drapery. While Reni's workshop in Rome was active primarily in the earlier part of the century, his influence persisted, and it's plausible Desubleo connected with him or his immediate followers during this Roman period, or perhaps more intensely when Reni was established back in Bologna and Desubleo himself moved north. The Roman artistic environment was incredibly rich, with figures like Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri), another Bolognese classicist, and the High Baroque dynamism of Pietro da Cortona beginning to emerge. French artists like Simon Vouet and Valentin de Boulogne were also active, bringing their own interpretations of Caravaggism and classicism.

The Bolognese Period: Consolidation and Maturity

By the mid-1620s, or perhaps a little later, Desubleo had moved from Rome to Bologna, a city with a distinguished artistic heritage, home to the Carracci Academy and a thriving school of painting. This move was likely influenced by Guido Reni, who had made Bologna his primary base of operations. It was in Bologna that Desubleo truly came into his own as an artist, absorbing the prevailing classicism of the Bolognese school while retaining subtle Flemish undercurrents.

In Bologna, Desubleo worked in close proximity to Reni, and his style became deeply imbued with the master's aesthetic. He adopted Reni's preference for harmonious compositions, idealized figures, and a palette that, while sometimes richer than Reni's later, more ethereal tones, still emphasized clarity and grace. He specialized in religious and mythological subjects, themes highly favored by Bolognese patrons. His figures often possess a gentle melancholy and a refined elegance that are hallmarks of Reni's influence. Other prominent artists in Bologna at the time included Alessandro Tiarini, Lionello Spada, and later, Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri), who, after a more Caravaggesque phase, also moved towards a more classical style.

During his Bolognese period, Desubleo produced a significant body of work. Among his notable commissions were paintings for local churches. For instance, he is documented as having created altarpieces and other religious works that demonstrated his mastery of the prevailing classical-Baroque style. One such example often cited is The Holy Family, which would have showcased his ability to handle tender religious narratives with grace and devotional sincerity. His figures, often characterized by smooth modeling and serene expressions, appealed to the sophisticated tastes of Bolognese patrons. The influence of other Reni followers, such as Simone Cantarini ("Il Pesarese") or Giovanni Andrea Sirani and his talented daughter Elisabetta Sirani, would also have been part of the artistic dialogue in the city.

Masterworks from the Bolognese Era

One of Desubleo's most compelling works, often associated with his Bolognese period or shortly thereafter, is David with the Head of Goliath. This painting, now housed in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna (though some sources place it in San Giovanni in Monte), exemplifies his mature style. The young David is depicted not in the heat of battle, but in a moment of calm, contemplative triumph. His figure is rendered with classical poise, his expression serene, almost melancholic, as he gazes towards the viewer or slightly away. The severed head of Goliath, typically gruesome, is handled with a degree of restraint, emphasizing the narrative rather than shock value. The composition is balanced, the lighting carefully managed to highlight David's youthful form against a darker background, a technique that shows a sophisticated understanding of chiaroscuro, perhaps a lingering echo of Caravaggesque drama tempered by Reni's classicism. The rich, yet controlled, color palette, with deep reds and earthy tones, adds to the painting's gravitas.

Another significant work is Tancred and Erminia, a subject drawn from Torquato Tasso's epic poem Jerusalem Delivered, a popular source for Baroque artists. Desubleo's version, with one notable example in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, captures the poignant moment when Erminia, discovering the wounded hero Tancred, cuts her hair to bind his wounds. The painting showcases Desubleo's skill in depicting tender emotion and dramatic narrative. The figures are elegant, their gestures expressive, and the drapery is rendered with characteristic softness. The composition likely balances the drama of the scene with a classical sense of order, reflecting the influence of Reni's narrative paintings. Such mythological and literary subjects allowed artists like Desubleo to explore a wider range of human emotions and to display their erudition.

Venetian Ventures and the Later Career

After a productive period in Bologna, Desubleo's career took him to Venice, probably by the 1650s. Venice, with its distinct artistic tradition heavily influenced by masters like Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, offered a different artistic climate. The Venetian emphasis on colorito (color and painterly application) over disegno (drawing and design, prized in Florence and Bologna) presented both opportunities and challenges for an artist steeped in Bolognese classicism.

In Venice, Desubleo continued to receive commissions, including works for ecclesiastical patrons. He is recorded as having painted for the Capuchin convent, contributing to the decoration of churches such as San Lorenzo and San Zaccaria. His style during this period may have shown some adaptation to Venetian tastes, perhaps a slight loosening of his brushwork or a warming of his palette, though he largely remained faithful to the classical principles absorbed from Reni. The Venetian art scene at this time included artists like Pietro Liberi and Francesco Maffei, who represented a more exuberant, painterly Baroque.

One of Desubleo's intriguing works from this period or reflecting his engagement with diverse themes is Ulysses and Nausicaa. This painting, with a version in the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, depicts the episode from Homer's Odyssey where the shipwrecked Ulysses encounters the princess Nausicaa and her handmaidens. Desubleo's rendition often highlights the modesty of Nausicaa as she offers aid to the hero. Interestingly, some interpretations of this scene by Desubleo are noted for including elements related to the game of tennis (jeu de paume), as Nausicaa and her attendants were playing ball when they discovered Ulysses. This inclusion of contemporary or unusual details adds a layer of interest to his mythological paintings.

His Madonna della Rosa (Madonna of the Rose), located in the Galleria Estense in Modena, is another testament to his skill in religious painting. The composition likely features the Virgin Mary and Child with a rose, a symbol rich in Marian iconography, often alluding to her purity or her title "Mystical Rose." Desubleo would have rendered this subject with his characteristic tenderness and refined execution, balancing devotional warmth with classical grace.

The Parma Years and Final Stylistic Evolution

The final phase of Michele Desubleo's career unfolded in Parma, where he is documented from around 1665 until his death in 1676. Parma, another city with a rich artistic legacy, notably that of Correggio and Parmigianino, provided the backdrop for his late works. During this period, his style continued to evolve, reportedly showing an engagement with the emerging Neoclassical tendencies, while still retaining the influence of the Venetian tradition and his foundational Bolognese classicism.

Works from his Parma period might exhibit a continued refinement of form, perhaps a cooler palette, and a heightened sense of order, aligning with the broader shift towards Neoclassicism that would gain momentum later in the century. However, the Venetian emphasis on color and light, experienced during his time in the lagoon city, likely also left a lasting impression, preventing his art from becoming overly rigid or academic.

The Allegory of Sacred and Profane Love, with an example in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, is a complex allegorical piece that showcases Desubleo's intellectual engagement and artistic versatility. Such allegories were popular in the Baroque era, allowing artists to explore abstract concepts through symbolic figures and attributes. Desubleo's interpretation would have involved carefully chosen iconography, perhaps contrasting figures representing spiritual and worldly love, surrounded by symbolic objects like musical instruments, books, or vanitas elements. The inclusion of musical instruments, painting tools, and sculpture in some of his allegorical works also points to a sophisticated reflection on the arts themselves.

His Portrait of King Solomon, if securely attributed and dated to this later period, would demonstrate his ability in portraiture, imbued with a sense of wisdom and regality. The depiction of Solomon, renowned for his wisdom, would have allowed Desubleo to combine portrait-like features with an idealized representation of a revered historical and biblical figure, likely adorned with rich robes and symbols of kingship, rendered with his characteristic attention to detail and texture.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of North and South

Michele Desubleo's artistic style is a compelling fusion of his Flemish origins and his profound immersion in Italian art, particularly the classicism of Guido Reni and the Bolognese school. His Flemish heritage is discernible in a certain meticulousness in the rendering of details, a sensitivity to textures (such as fabrics, hair, and flesh), and a subtle, often introspective, emotional quality in his figures. This Northern European inclination towards naturalism was, however, tempered and refined by Italian idealism.

The dominant influence on his style was undoubtedly Guido Reni. From Reni, Desubleo adopted:

1. Idealized Figures: His saints, mythological heroes, and heroines possess an idealized beauty, with smooth skin, elegant proportions, and graceful poses.

2. Classical Composition: Desubleo favored balanced, harmonious compositions, often with a clear narrative structure and a sense of calm and order, even in dramatic scenes.

3. Refined Emotional Expression: While capable of conveying deep emotion, his figures often exhibit a restrained pathos, a gentle melancholy, or serene contemplation, avoiding the overt theatricality seen in some other Baroque artists.

4. Soft Modeling and Luminous Palette: He employed soft transitions in modeling to create gentle, rounded forms. His color palette, while sometimes richer and warmer than Reni's later works, often featured luminous flesh tones and a sophisticated use of color harmonies.

Desubleo also showed an awareness of Caravaggesque naturalism, particularly in his handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create volume and drama, though this was generally subordinated to his classical framework. His time in Venice may have led to a slightly more painterly approach in some works, with a greater appreciation for the expressive qualities of color and brushwork, characteristic of the Venetian tradition stemming from artists like Titian and Veronese.

His thematic repertoire was typical of the era, focusing on religious scenes (Madonnas, saints, biblical narratives) and mythological or allegorical subjects. In all these, he demonstrated a consistent elegance and a technical polish that made his work appealing to patrons across different Italian cities. He was particularly adept at conveying tender or poignant moments, capturing subtle psychological states in his figures.

Interactions with Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Throughout his career, Desubleo was part of a vibrant network of artists. His initial connection with Abraham Janssens and his half-brother Nicolas Régnier was crucial for his entry into the art world and his journey to Italy. Régnier himself became a successful painter in Italy, known for his elegant figures that blended Caravaggesque and Bolognese influences, and the brothers likely maintained contact.

In Rome and Bologna, his association with Guido Reni was paramount. Being part of Reni's circle meant exposure to a highly refined artistic environment and interaction with other pupils and followers, such as the aforementioned Simone Cantarini, Giovanni Andrea Sirani, and Elisabetta Sirani. This environment fostered a shared aesthetic language, though individual artists like Desubleo developed their own nuances. The Bolognese school, with its strong academic tradition rooted in the teachings of the Carracci (Ludovico, Annibale, and Agostino), provided a fertile ground for artists focused on drawing, composition, and the study of classical and High Renaissance models. Desubleo's work fits comfortably within this tradition, alongside contemporaries like Alessandro Tiarini and, to some extent, the later classicizing phase of Guercino.

His time in Venice would have brought him into contact with a different set of artistic priorities and practitioners. While perhaps not fully assimilating the more flamboyant Venetian Baroque style of artists like Francesco Maffei or Pietro Liberi, he would have been aware of their work and the enduring legacy of the great Venetian masters of the 16th century. The presence of other foreign artists in these Italian centers also contributed to a cosmopolitan artistic exchange. Figures like the Frenchmen Simon Vouet and Valentin de Boulogne in Rome, or later, the German Johann Liss in Venice, enriched the Italian scene with their diverse perspectives.

Challenges of Attribution and Rediscovery

For a considerable period, Michele Desubleo's artistic identity was somewhat obscured, and his works were often misattributed to other artists, a common fate for painters who worked in a style closely aligned with a more famous master. His paintings have, at times, been confused with those of Nicolas Régnier, Guido Reni himself, or other followers of Reni like Simone Cantarini or even the Sassoferrato (Giovanni Battista Salvi) for their shared classical refinement.

The very nature of his style – a subtle blend of Flemish and Italian elements, deeply indebted to Reni yet possessing its own quiet distinction – made definitive attribution challenging without thorough connoisseurship and documentary evidence. His peripatetic career, moving between several artistic centers, also meant that his oeuvre was dispersed, and local art historical traditions might not have always consistently tracked his contributions.

However, in recent decades, art historical scholarship has made significant strides in reconstructing Desubleo's catalogue raisonné and re-evaluating his significance. Through careful stylistic analysis, archival research, and the identification of signed or documented works, a clearer picture of his artistic personality and achievements has emerged. Exhibitions and scholarly publications have helped to bring his name to greater prominence, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of his place within the complex artistic landscape of 17th-century Italy. This process of rediscovery highlights the importance of ongoing research in art history, which continually refines our understanding of artists who may have been temporarily overlooked. His Death of Cleopatra, for example, now in a private collection, or San Giovannino, showcase aspects of his style that, once identified, help to attribute other works.

Legacy and Influence

Michele Desubleo's legacy is that of a skilled and sensitive painter who successfully navigated the diverse artistic currents of 17th-century Italy, forging a distinctive style that blended his Northern European heritage with the dominant classicism of the Bolognese school. While he did not establish a large workshop or have a multitude of direct pupils in the way that his master Guido Reni did, his influence can be seen in the broader context of the diffusion of Reni's style and the ongoing dialogue between Flemish and Italian artistic traditions.

His works, found in churches and museums across Italy and beyond, stand as testament to his refined aesthetic and technical mastery. They contributed to the rich artistic production of the Seicento, offering patrons elegant and devotional images that were highly valued. His career also exemplifies the experiences of many "Fiamminghi" (Flemish artists) who sought fame and fortune in Italy, adapting their native styles to Italian tastes while often retaining a unique Northern sensibility. Artists like Anthony van Dyck, who also spent significant time in Italy, similarly synthesized Northern and Italian elements, albeit with a different focus on portraiture and a more aristocratic flair.

Desubleo's paintings, with their gentle emotionality, harmonious compositions, and subtle interplay of light and color, continue to appeal to modern viewers. The ongoing scholarly interest in his work ensures that his contributions to Baroque art are increasingly recognized. He represents a quieter, more introspective voice within the grandeur of the Baroque, an artist whose dedication to beauty and refined expression created a body of work that remains compelling and worthy of study. His ability to absorb and personalize the lessons of a giant like Guido Reni, while subtly infusing his work with his own Flemish background, marks him as a significant, if once underestimated, figure in the history of European art. His journey from Maubeuge to Parma, through the great artistic crucibles of Rome, Bologna, and Venice, is a story of artistic assimilation, refinement, and enduring creation.