Introduction: Unveiling Francisque Millet

Francisque Millet, also known during his time and in subsequent art history as Jean-François Millet or Millet I, stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the rich tapestry of 17th-century European landscape painting. Born in the bustling artistic hub of Antwerp in 1642, his relatively short life, ending in Paris in 1679, spanned a crucial period of stylistic transition and development in art. Primarily celebrated for his classical landscapes, Millet skillfully navigated the artistic currents of his time, blending his Flemish origins with the prevailing French classical ideals, leaving behind a body of work admired for its serene beauty, atmospheric depth, and narrative subtlety.

It is essential to distinguish this Francisque Millet (1642-1679) from the later, perhaps more widely known, Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), the prominent French Realist painter associated with the Barbizon School, famed for works like The Gleaners and The Angelus. Our focus here is solely on the 17th-century master, whose contributions lie firmly within the tradition of idealized landscape painting, drawing inspiration from the giants of the genre while forging his own distinct path. His career unfolded mainly in Paris, yet his Flemish roots remained an undercurrent in his artistic identity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Jean-François Millet, who would adopt the name Francisque, entered the world in Antwerp in 1642. At this time, Antwerp was still reverberating from its Golden Age, a city that had nurtured the prodigious talents of Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, establishing itself as a powerhouse of Baroque art. Though the peak had arguably passed, the city's artistic infrastructure, guilds, and traditions remained potent forces. Millet's own father was a sculptor, originally hailing from Dijon in France, who had presumably found opportunities in the vibrant artistic milieu of the Southern Netherlands.

Growing up in this environment undoubtedly exposed the young Millet to a high level of artistic production and craftsmanship. His initial training took place in Antwerp, immersing him in the Flemish artistic traditions, which often emphasized detailed observation, rich textures, and dynamic compositions. The source material suggests he followed his father in working for a court, likely within the Spanish Netherlands, gaining early exposure to patronage and perhaps the more formal demands of courtly art before his decisive move.

Around 1660, still a young man but presumably with foundational skills established, Millet made the pivotal decision to relocate to Paris. This move marked a significant shift, transplanting him from the heartland of Flemish Baroque to the epicenter of emerging French Classicism under the burgeoning reign of Louis XIV. This transition would profoundly shape his artistic trajectory, setting the stage for a career dedicated to landscape painting within a new cultural and aesthetic context.

Establishing a Career in Paris: The Classical Ideal

Arriving in Paris around 1660, Francisque Millet entered a city undergoing a cultural transformation. Under Louis XIV, Paris was solidifying its position as the political and artistic capital of Europe. The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), founded in 1648, was increasingly influential, promoting a hierarchy of genres that placed history painting at the apex, but also fostering a specific, ordered, and idealized approach to art known as Classicism. Landscape painting, while ranked lower than history painting, found a significant place within this system, particularly when imbued with historical, mythological, or biblical significance.

Millet quickly adapted to this new environment, achieving considerable success as an artist. He specialized in landscape painting, a genre gaining popularity among collectors and patrons. His ability to absorb and interpret the prevailing classical ideals, while perhaps retaining subtle elements of his Flemish training, allowed him to carve out a niche. He became known for his evocative depictions of the natural world, filtered through a lens of harmony, order, and often, a gentle melancholy.

His success indicates that his style resonated with the tastes of the time. Parisian collectors appreciated landscapes that offered an escape into an idealized nature, often reminiscent of the Roman Campagna, even if painted from imagination or based on sketches. Millet's works provided just that: beautifully composed scenes that spoke of tranquility and timelessness, aligning well with the classical preference for clarity, balance, and elevated sentiment.

The Pillars of Influence: Poussin and Claude Lorrain

Francisque Millet's artistic development was profoundly shaped by the towering figures of French Classicism, particularly Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) and Claude Lorrain (1600-1682). Although both Poussin and Claude spent most of their careers in Rome, their influence permeated French art, setting the standard for classical landscape painting. Millet absorbed their lessons, integrating their principles into his own burgeoning style. The source material even suggests he may have worked under Poussin's guidance at some point, though the exact nature of this relationship requires careful consideration, given Poussin's time primarily in Rome. It's more certain that Millet deeply studied Poussin's approach.

From Nicolas Poussin, Millet likely learned the importance of structure, intellectual rigor, and the integration of meaningful narrative within the landscape. Poussin's landscapes are carefully constructed stages for historical, mythological, or biblical events, where nature itself reflects the mood and significance of the human drama. Trees act like architectural elements, light defines form with clarity, and the overall composition conveys order and gravitas. Millet's own tendency to include figures and subtle narratives echoes Poussin's model, albeit often with a softer, less severe tone.

Claude Lorrain offered a different but complementary influence. Claude was the master of light and atmosphere, renowned for his poetic depictions of the Roman Campagna bathed in the golden light of dawn or dusk. His landscapes emphasize vast, luminous skies, hazy distances, and a sense of nostalgic tranquility. While Poussin focused on structure and narrative clarity, Claude prioritized mood, atmosphere, and the evocative power of light. Millet's works often capture a similar sensitivity to atmospheric effects and the poetic qualities of nature, particularly in his handling of light and distance, suggesting a close study of Claude's achievements.

Another significant figure within this classical landscape tradition was Gaspard Dughet (1615-1675), Poussin's brother-in-law, who also worked in Rome. Dughet specialized in landscapes that were perhaps less intellectually demanding than Poussin's but equally structured and often more focused on the naturalistic details of the Roman countryside, sometimes with a more dynamic or even stormy atmosphere. Millet's work, particularly his rendering of foliage and terrain, sometimes shows an affinity with Dughet's approach, suggesting Millet was familiar with the broader circle of Franco-Roman classical landscapists.

Flemish Roots and Italianate Connections

While Millet embraced the French classical style, his Flemish origins likely contributed certain nuances to his work. Flemish art, even in landscape, often retained a strong connection to tangible reality, a delight in texture, and a certain robustness that could subtly differentiate his work from purely French or Italian models. This might be seen in the "thick, expressive brushwork" noted in the source material, which could suggest a more tactile approach to paint handling than typically found in the smooth finishes of high Classicism.

His style also connects him to the tradition of "Italianate" painters – Northern European artists (from Flanders, the Dutch Republic, Germany) who travelled to Italy and absorbed the influence of the Italian landscape and the classical tradition. Jan Frans van Bloemen (1662-1749), known as 'Orizzonte', is mentioned as an influence or point of comparison. Although largely a contemporary whose main activity slightly post-dates Millet, Van Bloemen (a fellow Fleming) became famous in Rome for his expansive, idealized landscapes that clearly followed the path forged by Claude and Dughet. Millet's work shares characteristics with this broader Italianate movement, particularly the focus on idealized views inspired by the Italian countryside, even if Millet himself may not have travelled extensively to Italy.

The mention of Andrea Locatelli (1695-1741) as an inspiration is chronologically problematic if taken as a direct influence on Millet, as Locatelli belongs to a later generation. It's more likely that Millet's work anticipated certain aspects of later Rococo landscape painting or that both artists drew from the common wellspring of 17th-century classical landscape. Alternatively, the source might imply Millet's work inspired Locatelli, or simply places him within a stylistic lineage. Locatelli, working in Rome, continued the tradition of decorative landscapes, often lighter in tone than Millet's, but sharing a foundation in idealized nature.

To provide further context, Millet's serene classicism can be contrasted with the more dramatic, wild, and romantic landscapes being produced by contemporaries like the Italian Salvator Rosa (1615-1673), whose turbulent scenes of bandits and rocky wilderness offered a powerful alternative to the calm order of Poussin and Claude. Millet clearly aligned himself with the latter tradition. Another Flemish contemporary active in landscape was Abraham Genoels II (1640-1723), who, like Millet, was born in Antwerp and later worked in Paris and Rome, also producing classically inspired landscapes.

A Distinctive Artistic Signature: Style and Technique

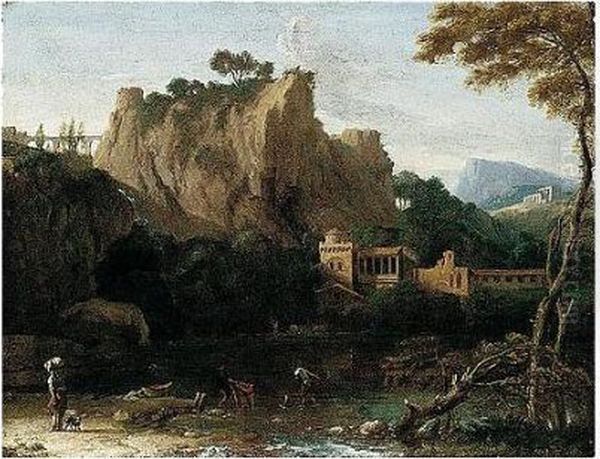

Francisque Millet forged a recognizable style characterized by several key elements. His landscapes often possess a distinct mood, frequently described as serene, tranquil, and sometimes imbued with a gentle melancholy. This atmosphere is partly achieved through his characteristic color palette, which often features prominent blues and blue-greens, lending his scenes an ethereal, almost dreamlike quality. This "blue tonality" became something of a hallmark, contributing to the overall coolness and detachment often associated with classical art, yet rendered with a unique sensitivity.

Technically, Millet's approach could be quite distinctive. The source material highlights his use of "thick, expressive brushwork." This suggests a departure from the very smooth, highly finished surfaces often favored by strict classicists. Such impasto, or textured application of paint, would add vibrancy and materiality to the canvas, drawing attention to the artist's hand and enhancing the physical presence of elements like foliage, rocks, and clouds. This technique might reflect a lingering connection to Flemish traditions, where tactile qualities were often emphasized.

Despite this potentially expressive brushwork, Millet remained committed to the classical principles of composition and light. His landscapes are carefully constructed, often employing established compositional devices like framing elements (trees, architecture) in the foreground, leading the eye through receding planes into a luminous distance. He demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), using light not just to illuminate the scene but also to define form, create depth, and enhance the overall mood. His handling of light could range from the clear, defining light of midday to more dramatic effects, as seen in specific works.

Furthermore, Millet's style incorporated a blend of natural observation and idealization. While his landscapes feel grounded and believable, they are ultimately constructs, idealized visions of nature perfected by art. He achieved a balance between rendering convincing details – the texture of bark, the formation of rocks, the play of light on water – and arranging these elements into a harmonious, ordered whole that transcended mere imitation. This blend of observation and invention is central to the classical landscape tradition he embraced.

Narrative Threads: Weaving Stories into Landscapes

Like many classical landscape painters following Poussin's example, Francisque Millet often integrated narrative elements into his scenes, drawing primarily from mythology and the Bible. These figures are typically small in scale relative to the vastness of the landscape, emphasizing humanity's place within a grand, ordered nature, or using the natural setting to amplify the story's emotional resonance. The landscape is rarely just a backdrop; it becomes an active participant in the narrative, its features and atmosphere contributing to the overall meaning.

The source mentions Hermes and Herse as one of his representative works. This subject, drawn from Ovid's Metamorphoses, tells a story of love, jealousy, and divine intervention. In depicting such a scene, Millet would use the landscape setting – perhaps a serene grove or a view towards a distant city – to establish the appropriate mood and context for the mythological figures and their interactions. The classical landscape provides a fittingly timeless and idealized stage for these ancient stories.

Another work alluded to in the stylistic description is Moses Saved from the Waters. This biblical subject, depicting the infant Moses being discovered in the bulrushes along the Nile by Pharaoh's daughter, was a popular theme in 17th-century art. For a landscape painter like Millet, it offered the opportunity to combine a significant religious narrative with an evocative riverine setting. The landscape elements – the river, the vegetation, the quality of light – would be carefully orchestrated to enhance the drama and poignancy of the discovery, underscoring themes of providence and salvation within the natural world.

These narrative inclusions elevated Millet's landscapes beyond mere decorative views. They invited contemplation, connecting the beauty of the natural world with enduring human stories and classical or religious values. This practice aligned perfectly with the expectations of academic art theory, which valued art that instructed and edified the viewer, even within the genre of landscape.

Exploring Key Works

While a comprehensive catalogue of Millet's authenticated works remains a subject of art historical study, certain paintings are consistently associated with him and exemplify his style. The source specifically mentions two: Mountain Landscape with Lightning and Hermes and Herse.

Mountain Landscape with Lightning suggests a departure from Millet's typically serene scenes, showcasing his ability to depict the more dramatic and sublime aspects of nature. A landscape struck by lightning allows the artist to explore dynamic contrasts of light and shadow, the turbulent energy of a storm, and the raw power of the natural world. This theme was also explored by contemporaries like Gaspard Dughet and later became central to Romantic landscape painting. For Millet, it would have been an opportunity to demonstrate his technical virtuosity in capturing fleeting atmospheric effects and intense emotion within a classical compositional framework. The characteristic blue tones might take on a more ominous quality in such a scene.

Hermes and Herse, as discussed earlier, places a mythological narrative within an idealized landscape. Such a work would likely feature elegantly posed figures integrated into a harmonious natural setting. The landscape itself might include classical architecture or ruins, further rooting the scene in antiquity. The focus would be on achieving a balance between the narrative action and the beauty of the surrounding environment, creating a poetic and elevated vision consistent with classical ideals. The rendering of light, perhaps the soft glow of morning or late afternoon, would be crucial in establishing the appropriate mythological atmosphere.

These examples highlight Millet's versatility within the classical landscape genre, capable of rendering both the peaceful and the dramatic, the pastoral and the mythological. His works consistently demonstrate a strong sense of composition, a sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and often, that distinctive cool, bluish palette.

Artistic Circle, Recognition, and Influence

During his time in Paris, Francisque Millet operated within a vibrant artistic community. The source mentions interactions with fellow landscape painters Henri Mauperché (c. 1602-1686) and Etienne Allegrain (1644-1736). Mauperché was an older contemporary, also known for classical landscapes often featuring ruins and biblical or mythological figures, working in a style influenced by Claude Lorrain and the Roman Campagna. Allegrain, closer in age to Millet, specialized in idealized landscapes that continued the classical tradition, known for their somewhat decorative quality and serene atmosphere, sometimes anticipating later Rococo sensibilities. Interaction with these artists suggests Millet was part of an active network of landscape specialists in Paris, sharing influences and perhaps competing for patronage.

Millet's reputation extended beyond France. The fact that the Dutch painter and engraver Gerard Hoet (1648-1733) copied or made prints after Millet's work is significant evidence of his recognition and influence. Hoet was a respected artist in his own right, known for his history paintings and elegant genre scenes. His engagement with Millet's landscapes indicates that Millet's compositions were admired and disseminated, reaching audiences in the Netherlands and likely elsewhere through the medium of print.

Despite his relatively short career, Millet achieved considerable success during his lifetime. His ability to synthesize Flemish elements with the dominant French classical style, particularly the influences of Poussin and Claude, resulted in a body of work that appealed to the tastes of 17th-century collectors. He was recognized as a skilled master of the idealized landscape.

Legacy and Conclusion

Francisque Millet passed away in Paris in 1679, not yet forty years old. His death cut short a promising career, leaving behind a body of work that nonetheless secured his place in the history of landscape painting. He stands as a fascinating example of an artist bridging different national traditions – born and trained a Fleming, he became a key practitioner of the French classical landscape.

His legacy lies in his contribution to the development and popularization of the idealized landscape in 17th-century France. He successfully adapted the grand models of Poussin and Claude Lorrain, infusing them with his own distinct sensibility, characterized by atmospheric depth, often cool tonalities, and sometimes expressive brushwork. His works offered viewers meticulously crafted visions of a harmonious, ordered nature, often enriched with narrative meaning.

While perhaps overshadowed in popular recognition by his influences (Poussin, Claude) and by the later, unrelated Jean-François Millet, Francisque Millet remains an important figure for understanding the complexities of 17th-century landscape painting. His art reflects the cross-currents of European styles and the specific aesthetic climate of Louis XIV's France. His son, Jean François Millet II (often called 'Francisque II'), followed in his footsteps as a landscape painter, continuing the family's artistic tradition, though Francisque I remains the more historically significant figure. Studying Francisque Millet reveals a talented artist who masterfully captured the serene beauty and enduring power of the classical landscape ideal.