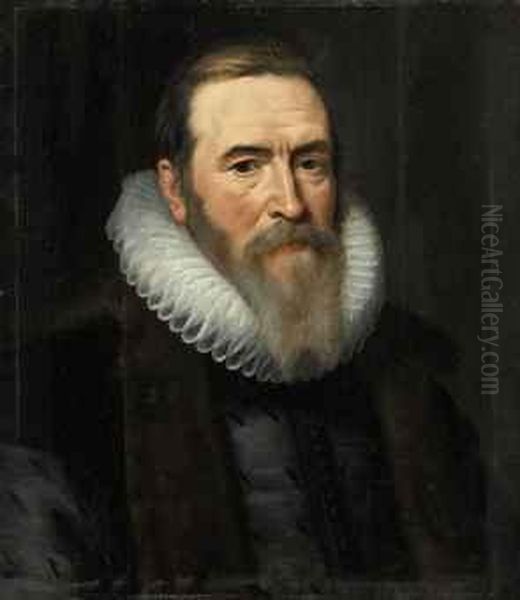

Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt stands as one of the most prolific and influential portrait painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Active primarily in Delft and The Hague, his career spanned several decades during a period of immense artistic flourishing in the Netherlands. Known for his remarkable technical skill, meticulous detail, and the sheer volume of his output, Mierevelt captured the likenesses of the Dutch elite, leaving behind a vast visual record of his time. While his birth year is cited with some contradiction, evidence predominantly points to 1567, marking the beginning of a life dedicated to art that would conclude in 1641.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt was born in the city of Delft, a prominent center for arts and crafts in the Dutch Republic. Sources present conflicting evidence regarding his exact birth date, suggesting either May 1, 1566, or, more commonly supported, May 1, 1567. He hailed from an artisanal background; his father, Jan Michelsz. van Miereveldt (1528–1612), was a respected goldsmith in the city. His mother was the daughter of a glass painter, further embedding the young Mierevelt in a world familiar with artistic creation and craftsmanship from an early age.

His initial artistic training began in Delft. He is recorded as having studied engraving, possibly under the tutelage of the renowned copperplate engraver Hieronymus Wierix (also known as Jeroen Wierix). He also received instruction from local painters Willem Willemsz. and possibly a master named Augusteyn. These early experiences would have grounded him in the fundamentals of drawing and composition, essential skills for any aspiring artist of the period.

A significant step in his development occurred around the age of fourteen. Mierevelt travelled to Utrecht, another important artistic hub, to study under the history painter Antonie van Blocklandt tot Montfoort. Blocklandt was a significant figure whose style, influenced by Italian Mannerism but adapted to Northern tastes, emphasized elegant figures and refined compositions. This period of study exposed Mierevelt to history painting, the most highly regarded genre at the time, and likely honed his skills in depicting the human form and narrative scenes. Some of Mierevelt's earlier works, such as depictions of Christ and the Samaritan Woman or Judith and Holofernes, reflect this training in history painting before he specialized in portraiture.

Following the death of Antonie van Blocklandt in 1583, Mierevelt returned to his native Delft. It was upon his return that he began to dedicate himself increasingly to portrait painting. This shift proved pivotal, setting the course for a long and exceptionally successful career catering to the growing demand for likenesses among the prosperous citizens of the Dutch Republic.

Rise to Prominence in Delft and The Hague

Back in Delft, Mierevelt quickly established himself. In 1587, he officially joined the Guild of Saint Luke in Delft, the professional organization for painters and other craftsmen. Membership was crucial for practicing artists, providing regulation, community, and a mark of professional standing. Mierevelt's talent and business acumen evidently impressed his peers, as he served multiple terms as headman (hoofdman) of the guild between 1589 and 1609, demonstrating his leadership within the local artistic community.

His reputation as a skilled portraitist grew rapidly. He became the preferred painter for the affluent burghers, mayors (burgomasters), and patrician families of Delft. His ability to capture a detailed and accurate likeness, presented with sobriety and dignity, perfectly suited the tastes of his clientele. His success was not confined to Delft; his fame spread to the nearby administrative and court center, The Hague.

A major milestone in his career came in 1607 when he was appointed court painter to Prince Maurice of Orange (Maurits van Oranje), the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. This prestigious appointment significantly elevated Mierevelt's social status and brought him into the highest circles of Dutch society. He painted numerous portraits of Prince Maurice and other members of the influential House of Orange-Nassau, solidifying his position as the leading portraitist of the political elite.

His connections extended beyond the Dutch borders. His workshop produced portraits of international figures, including George Villiers, the first Duke of Buckingham, a prominent English courtier. While some historical accounts mention potential, unfulfilled commissions involving the English court, such as a possible trip to paint King Charles I, concrete evidence for such journeys remains elusive. Regardless, his renown was certainly international.

Reflecting his strong ties to The Hague, Mierevelt also joined the Guild of Saint Luke in that city in 1625. Operating studios or maintaining significant professional connections in both Delft and The Hague allowed him to serve a broad and influential clientele across these two key Dutch cities throughout his mature career.

Artistic Style and Technique

Michiel van Mierevelt's artistic style is characterized by its meticulous realism, careful attention to detail, and a certain formal sobriety. Working within the traditions of the Dutch Golden Age, his primary aim was to produce accurate and recognizable likenesses of his sitters. His portraits are often described as rigorous, sincere, and highly finished, reflecting the values esteemed by his clientele.

His technique involved precise drawing and careful layering of paint to render textures, particularly fabrics like lace, silk, and velvet, with remarkable fidelity. He paid close attention to the play of light and shadow across the face and clothing, modeling forms convincingly and giving his subjects a tangible presence. The backgrounds are typically plain and dark, focusing attention entirely on the sitter. His colour palettes are generally harmonious and somewhat subdued, contributing to the dignified and often reserved atmosphere of his portraits.

While primarily known for portraiture, Mierevelt was also reportedly skilled in still life painting, a genre that similarly demanded close observation and detailed rendering. This versatility, though less emphasized in his surviving oeuvre, speaks to the breadth of his technical abilities grounded in the meticulous traditions of Netherlandish painting.

His style, while highly accomplished, is often seen as somewhat conservative, especially when compared to the more dynamic and psychologically penetrating works of contemporaries like Frans Hals or the later innovations of Rembrandt van Rijn. Mierevelt's approach was less focused on capturing fleeting expressions or deep emotional states and more on conveying the social standing and official likeness of the individual. His work reflects the influence of the late International Renaissance style he encountered through Blocklandt, adapted to the specific demands of Dutch portraiture.

In the 1630s, there is some indication that Mierevelt experimented with a slightly livelier and looser brushwork, perhaps responding to evolving artistic trends. However, he largely maintained the polished, detailed, and somewhat formulaic style that had brought him such immense success and catered effectively to market demands. His consistency and reliability were key components of his enduring appeal to patrons.

The Mierevelt Workshop and Prolific Output

One of the most astonishing aspects of Mierevelt's career is the sheer volume of work attributed to him. Some historical accounts, possibly exaggerated, estimate his output at over 10,000 paintings. While this number is likely inflated and includes numerous copies and workshop versions, it undeniably points to an exceptionally productive and well-organized studio operation.

Mierevelt ran a large and efficient workshop, employing numerous assistants and training many pupils. This workshop system was essential for meeting the high demand for his portraits. A significant portion of the works bearing his name were likely produced, at least in part, by these collaborators under his supervision. This practice was common among successful artists of the era.

To manage this high output, Mierevelt and his workshop often utilized standardized formats and compositional templates. Poses, clothing details, and background elements could be repeated or adapted, allowing for quicker production while maintaining a consistent style and quality associated with the master's brand. The faces, often the most crucial part requiring the master's touch, might be painted by Mierevelt himself, with assistants completing the costumes and backgrounds.

The numerous surviving versions of portraits of prominent figures like Prince Maurice attest to this practice. For instance, his portrait of the Prince, commissioned perhaps for the Delft City Hall, became a standard image that was copied repeatedly by the workshop for various patrons and institutions. This replication ensured wide dissemination of his work and contributed significantly to his fame and financial success. The existence of collective works, such as family portraits potentially involving contributions from multiple hands within the studio, further illustrates this collaborative mode of production.

Notable Sitters and Representative Works

Throughout his long career, Mierevelt painted a veritable 'who's who' of Dutch society and beyond. His most prominent patron was undoubtedly Prince Maurice of Orange, whose image he helped define for posterity through numerous portraits. He also painted other members of the House of Orange-Nassau, solidifying his role as a court painter.

Beyond the court, his sitters included influential politicians, wealthy merchants, high-ranking military officers, scholars, and their families, primarily from Delft and The Hague. His work provides an invaluable visual archive of the Dutch elite during a formative period in the nation's history. As mentioned, international figures like the Duke of Buckingham also sat for him, highlighting his reach.

Among his many works, several stand out or are frequently cited as representative of his style:

Portrait of Willem Jacobsz. Doff: This work exemplifies his skill in capturing a strong likeness and rendering textures with precision.

Portraits of Burgomasters and Officials: Numerous portraits, such as the generic Portrait of a Burgomaster, showcase his role in documenting the civic leadership of Delft and The Hague.

Portraits of Ladies: Works titled Portrait of a Lady or specifically dated ones like Portrait of a 58-Year-Old Lady demonstrate his ability to depict female sitters with dignity, often highlighting their elaborate attire and jewellery.

Portrait of Prince Maurice of Orange: Perhaps his most frequently reproduced work, existing in many versions, establishing the standard likeness of the Stadtholder.

While his early history paintings like Christ and the Samaritan Woman and Judith and Holofernes are less typical of his mature career, they are important indicators of his training under Antonie van Blocklandt. The vast majority of his known work, however, remains firmly within the genre of portraiture.

Family Life and Painter Sons

Michiel van Mierevelt married twice during his life, both ceremonies taking place in Delft. His first marriage occurred in 1589. From this union, he had at least three sons, two of whom followed him into the painting profession. His second marriage took place much later, in 1633. An unusual detail surrounds this second marriage: his bride was reportedly the daughter of his own stepmother, Anna van Huijssen (c. 1566–1644), whom he married after Anna's death.

His artistic legacy extended directly through his family. His son, Pieter van Miereveldt (1596–1623), became a capable portrait painter, working closely within his father's style and workshop until his early death. Another son, Jan van Miereveldt (1604–1633), also pursued a career as a painter, likely specializing in portraiture as well, though his life was also cut short. Their work often closely resembles their father's, sometimes making definitive attribution challenging, further complicating the study of the Mierevelt workshop's vast output.

Influence and Legacy

Michiel van Mierevelt's influence on Dutch Golden Age painting was significant, primarily through his dominance in the field of portraiture in Delft and The Hague for several decades and through the artists he trained. His workshop served as an important training ground. Notable pupils who went on to have successful careers of their own include Paulus Moreelse, who became a leading painter in Utrecht, and Antonie Palamedesz., known for his portraits and genre scenes, particularly guardroom interiors ('kortegaardjes').

His impact was also felt through the sheer ubiquity of his (and his workshop's) portraits. The standardized, reliable, and highly detailed style he perfected set a benchmark for formal portraiture in the region. His works were widely disseminated through originals and copies, influencing the visual culture and the expectations of patrons regarding portraiture. He can be seen as establishing a 'Delft style' of portraiture that was influential before the rise of artists like Johannes Vermeer, who took Delft painting in a different direction later in the century.

While his artistic approach might be viewed as less innovative or emotionally resonant than that of giants like Rembrandt or Frans Hals, Mierevelt's contribution lies in his consistent quality, his prolific output, and his role in documenting the key figures of his time. He operated successfully within the market, providing a highly sought-after service with professionalism and skill. His contemporaries included other successful portraitists like Jan van Ravesteyn in The Hague, but Mierevelt's output and court connections arguably gave him pre-eminence for a significant period.

Later Life and Death

Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt remained active as a painter into his later years. Even as artistic tastes began to shift towards the more dynamic styles emerging in Amsterdam and Haarlem, he maintained his successful practice, adapting slightly perhaps, but largely adhering to the meticulous style that had served him so well. He continued to live and work primarily in Delft.

He died on June 27, 1641, at the advanced age of 74 (or 75, depending on the birth year used). He was buried in the Oude Kerk (Old Church) in Delft, the final resting place of many prominent Delft citizens, including, later, the painter Johannes Vermeer. His death marked the end of an era for portrait painting in Delft and The Hague.

Conclusion

Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt was a towering figure in Dutch Golden Age portraiture. His career, built on technical mastery, astute management of a large workshop, and an ability to meet the demands of an elite clientele, resulted in an unparalleled body of work. He provided Delft, The Hague, and the Dutch Republic with enduring images of its leaders and prominent citizens during a crucial period of its formation. While perhaps lacking the revolutionary genius of some contemporaries, his meticulous realism, consistent quality, and the sheer scale of his production secured his place as one of the most successful and influential painters of his time. His legacy endures not only in the numerous portraits held in museums worldwide but also through the artists he trained and the standard he set for formal portraiture in the Dutch Golden Age.