The Dutch Golden Age, spanning roughly the 17th century, was a period of extraordinary artistic efflorescence in the Netherlands. While masters like Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, and Frans Hals often dominate popular imagination, a constellation of highly skilled artists contributed to the rich tapestry of this era. Among them, Jan de Baen carved out a significant niche as a preeminent portrait painter, particularly favored by the elite in The Hague. His work, characterized by its dignified elegance and keen observation, offers a valuable window into the personalities and societal structures of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Jan de Baen was born in Haarlem, a vibrant center of art, in 1633. His early life was marked by personal loss; his parents passed away when he was still a child. Consequently, he was taken in by his uncle, Hinderk Pyp, a painter in Emden. It was likely here that De Baen received his initial exposure to the rudiments of art. However, his formal artistic training commenced in Amsterdam around 1645, when he became a pupil of Jacob Adriaensz Backer.

Backer was a prominent portrait and history painter, himself a student of Lambert Jacobsz and influenced by the broader currents of Amsterdam's art scene, which included figures like Rembrandt. Under Backer's tutelage, which lasted until approximately 1648 or perhaps even until Backer's death in 1651, De Baen would have honed his skills in drawing, composition, and the application of paint. Backer's style, known for its smooth finish, rich colors, and ability to capture a sitter's likeness with a certain gravitas, undoubtedly left an imprint on the young De Baen. This period in Amsterdam was crucial, as the city was the bustling commercial and artistic heart of the Dutch Republic, offering unparalleled opportunities for learning and observation.

Ascent in The Hague: A Courtly Portraitist

After his formative years in Amsterdam, Jan de Baen relocated to The Hague around 1660. This move was a strategic one. The Hague was the political center of the Dutch Republic, home to the States General, the Stadtholder's court (when applicable), and numerous foreign embassies. Such an environment naturally created a high demand for portraiture, as officials, diplomats, and aristocrats sought to commemorate their status and achievements.

De Baen quickly established himself as a leading portraitist in the city. He joined the Confrerie Pictura, the painters' guild of The Hague, in 1664, a testament to his recognized professional standing. His ability to imbue his subjects with an air of dignity and importance, combined with a refined technique, resonated well with the tastes of the elite. He became a sought-after artist, rivaling other established portrait painters in The Hague such as Adriaen Hanneman, who had brought an elegant Van Dyckian flair to the city, and later, the meticulous Caspar Netscher. De Baen's success was such that he was even considered for a position at the English court of Charles II, though this ultimately did not materialize, possibly due to the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

Notable Patrons and Celebrated Sitters

Jan de Baen's clientele included some of the most influential figures of his time. His most famous patrons were undoubtedly the De Witt brothers: Johan de Witt, the Grand Pensionary of Holland, and Cornelis de Witt, his brother and a prominent naval officer and statesman. De Baen painted several portraits of Johan de Witt, capturing the intelligence and authority of the man who effectively governed the Dutch Republic for nearly two decades during the First Stadtholderless Period. These portraits became iconic representations of the statesman.

He also painted Cornelis de Witt, often depicted with attributes alluding to his naval exploits, such as the Raid on the Medway. The tragic fate of the De Witt brothers in the "Rampjaar" (Disaster Year) of 1672, when they were brutally murdered by an Orangist mob, cast a somber shadow. De Baen himself experienced the political fury of the time when one of his portraits of Cornelis de Witt, displayed in the Dordrecht town hall, was defaced by the enraged populace.

Beyond the De Witts, De Baen portrayed numerous other dignitaries. He was commissioned to paint William III, Prince of Orange, who would later become King of England. His portraits of William III helped to craft the image of the young prince as a determined leader. Foreign rulers also sought his talents; Frederick William, the "Great Elector" of Brandenburg, was among his distinguished sitters. The breadth of his patronage underscores his reputation, which extended beyond the borders of the Dutch Republic. He also painted group portraits, such as "The Regents of the Walenweeshuis (Walloon Orphanage) in Amsterdam," demonstrating his versatility within the portrait genre.

Artistic Style and Technical Prowess

Jan de Baen's artistic style is best characterized by its elegant realism and sophisticated presentation. He absorbed the lessons of his master, Jacob Adriaensz Backer, particularly in achieving a smooth, polished finish and a convincing likeness. However, his work also shows an awareness of the prevailing international courtly style, largely popularized by Sir Anthony van Dyck. While De Baen may not have possessed Van Dyck's sheer painterly bravura or psychological depth, he successfully adapted elements of this aristocratic aesthetic to suit his Dutch clientele.

His portraits typically feature subjects in dignified, often formal poses, adorned in rich attire that signaled their social standing. De Baen paid meticulous attention to the rendering of fabrics – silks, velvets, lace – capturing their textures with considerable skill. His figures are usually well-lit, often against a darker, neutral background, which helps to emphasize their presence. While his primary focus was on conveying status and likeness, his portraits are not devoid of character. He managed to capture a sense of the individual's personality, albeit within the conventions of formal portraiture of the period.

Compared to the more introspective and psychologically penetrating portraits of Rembrandt, De Baen's work is more outwardly focused, emphasizing the public persona of his sitters. His style was less rugged than that of Frans Hals, aiming for a more refined and composed depiction. He found a successful middle ground that appealed to the tastes of the powerful and wealthy, who desired portraits that were both accurate and flattering, conveying authority and respectability. His palette was generally rich but controlled, contributing to the overall sense of gravitas in his works.

Key Works and Their Enduring Significance

Several of Jan de Baen's paintings stand out as particularly representative of his skill and historical importance.

His various portraits of Johan de Witt are perhaps his most iconic. These works, such as the one now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, depict the Grand Pensionary with a calm, intelligent gaze, dressed in sober but high-quality attire. They project an image of capable statesmanship and intellectual rigor, fitting for the man who guided the Dutch Republic through complex political and military challenges. The very existence of multiple versions and copies attests to their contemporary significance.

The portraits of Cornelis de Witt are equally compelling. Often shown with attributes of his naval career, such as a commander's baton or a distant sea battle, these paintings celebrate his role as a military hero, particularly his involvement in the successful Raid on the Medway during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The portrait that was famously defaced in Dordrecht highlights the intense political passions of the era and the power of images to evoke strong reactions.

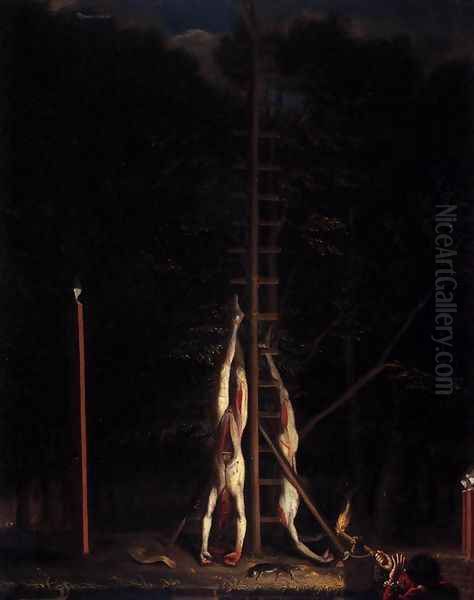

A more unusual and stark work is "The Corpses of the De Witt Brothers" (circa 1672-1675), attributed to Jan de Baen or his circle. This grim painting depicts the mutilated bodies of Johan and Cornelis hanging upside down after their lynching. It is a shocking and powerful piece of visual reportage, capturing the brutality of the event. While its direct attribution to De Baen himself is debated by some scholars, it reflects the profound impact of the murders and the demand for images related to this pivotal moment in Dutch history. If by De Baen, it shows a different, more visceral side to his art.

His portraits of William III, Prince of Orange, were also crucial. As William's political star rose, particularly after 1672, portraits by respected artists like De Baen helped to solidify his image as the nation's leader and savior. These works often show him in armor, emphasizing his military role and resolve.

De Baen also painted a Self-Portrait (circa 1675-1680), now in the Rijksmuseum, which shows him as a confident and successful artist, holding the tools of his trade. It is a valuable insight into how he wished to be perceived by his contemporaries.

Other notable works include portraits of figures like Hieronymus van Beverningh, a key diplomat, and various group portraits of regents, which, while less numerous than his individual commissions, demonstrate his ability to handle complex compositions involving multiple figures. These paintings collectively provide a visual record of the Dutch elite in the latter half of the 17th century.

Anecdotes and Glimpses into Character

Historical records and anecdotes offer glimpses into Jan de Baen's personality and principles. One of the most famous stories concerns his interaction with King Charles II of England. According to Arnold Houbraken, the early 18th-century biographer of Dutch artists, De Baen was invited to England to work for the King. During a visit to De Baen's studio (or perhaps while De Baen was considering the offer), Charles II supposedly saw a portrait of Cornelis de Witt, an enemy of England during the Anglo-Dutch Wars. The King allegedly requested that De Baen remove or turn around the portrait of his adversary.

De Baen, in a display of Dutch patriotism and loyalty to his patrons, reportedly refused, stating that Cornelis de Witt had been a good patron to him. This act of defiance, if true, speaks volumes about De Baen's character and his unwillingness to compromise his principles, even for royal favor. It's also suggested that this incident, or the ongoing hostilities between England and the Dutch Republic, may have been a reason why De Baen ultimately did not take up a permanent position at the English court, where artists like Sir Peter Lely and later Sir Godfrey Kneller (both of foreign origin themselves) enjoyed immense success.

Another anecdote, related to the defacement of his portrait of Cornelis de Witt in Dordrecht after the brothers' murder in 1672, illustrates the volatile political climate. While not a reflection on De Baen's character directly, it shows how deeply his work was intertwined with the political fortunes and public perception of his sitters. The artist himself was reportedly distressed by this act of vandalism against his work.

These stories, whether entirely factual or embellished over time, contribute to the image of Jan de Baen as a respected and principled artist, deeply embedded in the socio-political fabric of his era. He was known to be a diligent and prolific painter, maintaining a busy studio to meet the demand for his work.

Contemporaries, Artistic Milieu, and Influence

Jan de Baen operated within a thriving and competitive artistic environment. His initial training with Jacob Adriaensz Backer in Amsterdam placed him in a city bustling with talent. Amsterdam was dominated by figures like Rembrandt van Rijn, whose profound psychological insight and innovative techniques set a high bar, and Bartholomeus van der Helst, who became the city's most fashionable portraitist from the 1640s onwards, known for his smooth, detailed, and flattering likenesses. De Baen's style, in its polish and elegance, perhaps owed more to the trends exemplified by Van der Helst than to Rembrandt's more rugged naturalism.

Upon moving to The Hague, De Baen entered a different but equally competitive scene. Adriaen Hanneman, who had worked in England and absorbed the style of Anthony van Dyck, was a leading figure there, known for his aristocratic portraits. Other notable portraitists in The Hague included Pieter Nason and, emerging around the same time as De Baen, Caspar Netscher, who was also highly successful with his refined, small-scale portraits and genre scenes. De Baen had to distinguish himself amidst these talents, and he did so by consistently producing high-quality, dignified portraits that met the expectations of a discerning clientele.

His work should also be seen in the broader context of Dutch Golden Age portraiture, which included masters like Frans Hals in Haarlem, known for his lively and spontaneous characterizations. While De Baen's approach was more formal than Hals's, the overall emphasis on capturing individual likeness was a hallmark of Dutch art. He was also a contemporary of artists like Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck, both former pupils of Rembrandt who later adopted a more elegant, internationally influenced style popular with wealthy patrons.

De Baen's influence can be seen in the work of his pupils and followers. He maintained an active workshop, and his style of formal, yet perceptive portraiture became a standard for official and private commissions in The Hague.

Pupils and the Workshop Tradition

Like many successful artists of his time, Jan de Baen ran a workshop and trained a number of pupils. This was a common practice, allowing established masters to meet the demand for their work, disseminate their style, and contribute to the education of the next generation of artists.

His most notable pupil was arguably his own son, Jacobus de Baen (1673-1700). Jacobus showed considerable promise as a painter, following closely in his father's stylistic footsteps. He accompanied his father on a trip to England, where he reportedly impressed with his talent. Tragically, Jacobus de Baen died young, at the age of 27, cutting short a potentially distinguished career. His death was undoubtedly a great personal and professional loss for his father.

Other pupils who studied under Jan de Baen include Nicolaes van Ravesteyn II, Johan Vollevens I, and Constantijn Netscher (son of Caspar Netscher, though this connection is sometimes debated). These artists went on to have careers of their own, and their work often reflects the influence of De Baen's elegant and dignified approach to portraiture. For instance, Johan Vollevens I became a respected portrait painter in The Hague, effectively continuing the tradition established by De Baen.

The existence of a busy workshop also helps to explain the variations and studio versions of some of De Baen's popular portraits, particularly those of prominent figures like the De Witt brothers or William III. Demand for such images was high, and studio assistants would have played a role in producing copies or versions under the master's supervision. This practice was standard and ensured that the artist's popular compositions could be widely disseminated.

Later Years, Death, and Lasting Legacy

Jan de Baen continued to be a highly respected and active painter throughout his career. He remained based in The Hague, which was the center of his professional life and success. His reputation as a skilled portraitist ensured a steady stream of commissions from both Dutch and international clientele. Even as artistic tastes began to evolve towards the end of the 17th century, De Baen's classic, dignified style retained its appeal for formal portraiture.

He passed away in The Hague in March 1702, and was buried in the Kloosterkerk. By the time of his death, he had established himself as one of the leading portrait painters of the Dutch Golden Age, particularly associated with the political elite of The Hague.

In art historical evaluation, Jan de Baen is recognized as a highly competent and significant artist within his specific domain. While he may not be celebrated for radical innovation in the same way as Rembrandt or Vermeer, his contribution to the genre of portraiture was substantial. He skillfully blended Dutch realism with an international courtly elegance, creating a style that perfectly suited the requirements of his patrons. His portraits are invaluable historical documents, providing vivid likenesses of the men and women who shaped the Dutch Republic during a critical period.

His influence extended through his pupils and set a standard for official portraiture in The Hague that persisted for some time. Though perhaps overshadowed in popular accounts by some of his more famous contemporaries, Jan de Baen's oeuvre remains a testament to the depth and diversity of talent in the Dutch Golden Age, and his works continue to be studied for their artistic merit and historical insights. He successfully navigated the competitive art market, built a prestigious career, and left behind a legacy of finely crafted portraits that capture the essence of an era.

Conclusion: An Enduring Image-Maker

Jan de Baen stands as a figure of considerable importance in the narrative of 17th-century Dutch art. As a master portraitist, he not only captured the physical likenesses of his sitters but also conveyed their status, character, and the societal values of their time. From the powerful statesmen Johan and Cornelis de Witt to Prince William III and numerous other dignitaries, De Baen's brush chronicled the faces of power and influence in the Dutch Republic and beyond. His ability to combine technical skill with an understanding of his patrons' desires for dignified representation secured him a prominent place in the artistic landscape of The Hague. While the Dutch Golden Age boasts many luminaries, Jan de Baen's dedicated career in portraiture provides an indispensable visual record, making him a key artist for understanding the people and the period. His legacy is preserved in the numerous portraits that hang in museums and collections worldwide, silent witnesses to a vibrant and tumultuous age.