Wojciech Gerson (1831-1901) stands as one of the most significant figures in the history of Polish art, a pivotal artist during the 19th century, a period of immense cultural and national significance for Poland. His multifaceted career as a painter, esteemed educator, insightful art critic, and active participant in cultural life left an indelible mark on the development of Polish Realism. Gerson's dedication to depicting the Polish landscape, its people, and its history, combined with his profound influence on a generation of artists, cemented his legacy as a cornerstone of Poland's artistic heritage. This exploration delves into his life, artistic journey, key works, pedagogical impact, and his enduring influence on the trajectory of Polish art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Warsaw on July 1, 1831, Wojciech Gerson's early life unfolded in a city that, despite being under foreign partition, was a vibrant center of Polish cultural and intellectual activity. His innate artistic talent became apparent early on, leading him to enroll in the Warsaw School of Fine Arts in 1844. There, he studied under notable Polish artists of the time, including Jan Feliks Piwarski, Chrystian Breslauer, and Marcin Zaleski. These formative years provided him with a solid grounding in academic drawing and painting techniques, instilling a discipline that would underpin his later, more expressive works.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Gerson, like many aspiring artists of his era, traveled to St. Petersburg in 1853. He gained admission to the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts, where he studied historical painting under the tutelage of Alexey Tarasovich Markov. His time in St. Petersburg exposed him to a different academic tradition and allowed him to engage with a wider artistic community. He also benefited from the instruction of other Russian masters, though Markov's influence on his historical compositions was particularly notable.

The allure of Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world, drew Gerson in 1856. He enrolled in the studio of Léon Cogniet, a respected academic painter known for his historical scenes and portraits. Cogniet's atelier was a hub for international students, and Gerson's time there was crucial for his development. Beyond formal instruction, he immersed himself in the Parisian art scene, diligently studying the works of Old Masters in the Louvre and engaging with contemporary artistic currents. He was particularly drawn to the burgeoning Realist movement and the plein-air practices of the Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet, whose dedication to capturing nature and rural life resonated with his own inclinations.

The Emergence of a Realist Vision

Upon his return to Warsaw in 1858, Gerson embarked on a career that would define him as a leading proponent of Realism in Poland. The socio-political context of partitioned Poland, yearning for national identity and cultural expression, deeply influenced the themes and subjects he chose. Realism, with its emphasis on objective representation of contemporary life and the natural world, offered a powerful means to explore and affirm Polish identity.

Gerson's Realism was not merely a stylistic choice but a profound commitment to truthfulness in art. He believed in meticulous observation and direct experience as the foundation for artistic creation. This philosophy manifested in his diverse oeuvre, which encompassed majestic landscapes, poignant historical narratives, intimate genre scenes depicting rural life, and insightful portraits. He eschewed idealized or overly sentimental depictions, striving instead for an authentic portrayal of his subjects.

His early works after returning to Poland already showcased his developing Realist sensibilities. He began to travel extensively throughout Poland, particularly drawn to the Tatra Mountains and the rural countryside. These excursions provided him with a rich repository of subjects and a deep understanding of the Polish land and its inhabitants.

Landscapes: Capturing the Polish Soul

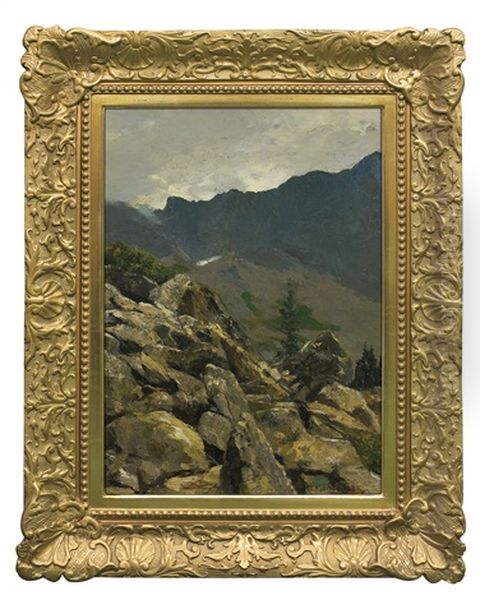

Gerson's contribution to Polish landscape painting is particularly significant. He was one of the first Polish artists to systematically explore and depict the diverse beauty of the Polish terrain, especially the majestic and then relatively untamed Tatra Mountains. His landscapes were not mere topographical records but deeply felt interpretations of nature, imbued with a sense of national spirit and a profound connection to the land.

Works like Mountain Landscape (1898) and Cemetery in the Mountains (1894) exemplify his approach. In Mountain Landscape, he captures the grandeur and ruggedness of the Tatras, using a palette that reflects the atmospheric conditions and the specific character of the region. His compositions often emphasize the vastness and permanence of nature, sometimes with small human figures that highlight the scale of the mountains. Cemetery in the Mountains is a more somber piece, reflecting on themes of life, death, and memory within the imposing natural setting. The painting evokes a sense of quiet dignity and the enduring presence of human history within the timeless landscape.

His earlier work, Resting in a Shelter in the Tatra Mountains (1862), combines landscape with genre elements, depicting shepherds in a mountain hut. This piece showcases his interest in the local customs and the harmonious relationship between the people and their environment. Gerson's dedication to plein-air sketching, though often completed in the studio, lent an immediacy and authenticity to his landscapes. He meticulously observed the effects of light and atmosphere, striving to convey the unique character of each location. His depictions of the Vistula River and the plains of Mazovia also hold an important place in his landscape oeuvre.

Other artists who explored Polish landscapes, though perhaps with different stylistic emphases, include his own students like Józef Chełmoński and Leon Wyczółkowski, who would later develop their own distinctive approaches to landscape painting, often influenced by Impressionism and Symbolism. Earlier figures like Aleksander Orłowski had also depicted Polish scenes, but Gerson brought a new level of Realist intensity and national focus to the genre.

Historical Narratives: Patriotism and Identity

Historical painting held a special significance in 19th-century Poland. In a nation deprived of political sovereignty, historical art became a crucial medium for preserving national memory, celebrating past glories, and fostering patriotic sentiment. Gerson made significant contributions to this genre, creating works that resonated deeply with the Polish public.

His historical paintings were characterized by careful research, attention to detail in costumes and settings, and a desire to convey the psychological drama of the events depicted. Death of Przemysław II (1887) is a powerful example, portraying the tragic assassination of the Polish king. The composition is dramatic, focusing on the vulnerability of the dying king and the treachery of his assailants. Gerson's academic training is evident in the skilled rendering of figures and the complex arrangement of the scene.

Another notable historical work is Margrave Gero and the Slavs. This painting depicts a dramatic confrontation from early medieval history, reflecting the complex historical relationships between Germanic and Slavic peoples. Such themes allowed Gerson to explore issues of power, conflict, and cultural identity that had contemporary relevance for Poles living under foreign rule. His painting Copernicus in Rome, Lecturing on His System also highlights a moment of Polish intellectual triumph on the European stage, celebrating the legacy of the great astronomer.

Gerson's approach to historical painting can be compared and contrasted with that of his contemporary, Jan Matejko, the preeminent Polish historical painter of the era. While Matejko's canvases were often grander in scale and more overtly nationalistic and symbolic, Gerson's historical works, while patriotic, often displayed a more restrained Realism and a focus on the human dimension of historical events. Both artists, however, played crucial roles in shaping Poland's visual understanding of its past. Other artists engaging with historical themes included Henryk Siemiradzki, known for his grand academic scenes often set in antiquity, and Artur Grottger, whose poignant cycles depicted the tragedy of the January Uprising.

Genre Scenes and Portraits: The Fabric of Polish Life

Beyond grand landscapes and historical dramas, Gerson was a keen observer of everyday Polish life, particularly in rural communities. His genre scenes capture the customs, traditions, and daily labors of the peasantry with empathy and respect. These works contributed to a broader artistic interest in folk culture that was emerging across Europe, often intertwined with nationalist sentiments.

His illustrations for the book Polish National Costumes (Ubiory ludu polskiego, 1855), created in collaboration with the ethnographer Oskar Kolberg, are a testament to his early interest in documenting Polish folk traditions. These detailed and accurate renderings of regional attire are valuable both as artistic works and ethnographic records. Later genre paintings continued to explore rural themes, depicting market scenes, agricultural work, and village gatherings.

Gerson was also an accomplished portraitist. His portraits are characterized by their psychological insight and honest depiction of the sitter. He painted numerous prominent figures of Warsaw society, as well as more intimate portraits of family and friends. Portrait of Jadwiga ze Szpetry Strachockiej is an example of his skill in this genre, capturing the personality and social standing of the subject with sensitivity and technical finesse. His portraits, like his other works, adhere to Realist principles, avoiding flattery in favor of a truthful representation.

The interest in genre scenes was shared by many of his students, most notably Józef Chełmoński, who became famous for his dynamic depictions of Ukrainian and Polish rural life, often featuring horses. Aleksander Gierymski and his brother Maksymilian Gierymski were also key figures in Polish Realism, with Aleksander particularly known for his poignant scenes of life in Warsaw's poorer districts.

A Prolific Educator: Shaping a Generation

Wojciech Gerson's impact as an educator was perhaps as profound as his artistic output. For nearly three decades, from 1872 to 1896, he served as a professor at the Warsaw School of Drawing (formerly the School of Fine Arts, and often referred to as the "Klasa Rysunkowa"). During this long tenure, he mentored and inspired a generation of artists who would go on to shape the course of Polish art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

His teaching methods emphasized rigorous academic training, particularly in drawing, which he considered the foundation of all art. He encouraged his students to study nature directly, to develop their observational skills, and to strive for truthfulness in their representations. While he was a staunch advocate of Realism, he also fostered an environment where students could explore their individual talents and artistic inclinations.

Among his most distinguished students were some of the leading names in Polish art:

Józef Chełmoński: Renowned for his dynamic and atmospheric depictions of Polish and Ukrainian rural life, particularly his famous horse scenes.

Leon Wyczółkowski: A versatile artist who excelled in painting, graphics, and drawing, moving from Realism towards Impressionism and Symbolism, known for his landscapes, portraits, and floral studies.

Władysław Podkowiński: A pioneer of Polish Impressionism, whose tragically short career produced some of the most iconic Impressionist works in Polish art.

Józef Pankiewicz: Another key figure in Polish Impressionism and later Post-Impressionism, who also played an important role in introducing modern French art to Poland.

Jan Stanisławski: A master of small-format landscape painting, associated with the Young Poland movement, known for his evocative and atmospheric depictions of the Polish and Ukrainian countryside.

Stanisław Lentz: A prominent portraitist and professor at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts, known for his realistic and psychologically insightful portraits.

Wojciech Kossak: Though from a famous artistic dynasty and later developing his own style, particularly in battle scenes, he also benefited from Gerson's instruction.

Ludomir Benedyktowicz: A painter and writer, known for his landscapes and genre scenes, who overcame the loss of both hands to continue his artistic career.

Eligiusz Niewiadomski: An art critic and painter, later infamous for his assassination of President Gabriel Narutowicz, but in his earlier years a student of Gerson.

Kazimierz Alchimowicz: A painter known for his historical scenes and depictions of Lithuanian life and mythology.

Gerson's dedication to his students and his commitment to fostering a vibrant artistic environment in Warsaw were instrumental in the development of Polish art during a challenging period. He provided a crucial link between academic tradition and emerging modern artistic trends.

Beyond the Canvas: Critic, Writer, and Organizer

Wojciech Gerson's contributions to Polish cultural life extended beyond his painting and teaching. He was an active art critic, writing reviews and articles for various Polish journals, including the influential Tygodnik Ilustrowany (Illustrated Weekly). His criticism was informed by his deep knowledge of art history and his commitment to Realist principles. He sought to educate the public and to promote high standards in contemporary art.

He was also an author and translator. He wrote a biography of the painter Józef Simmler, another important figure in 19th-century Polish art. Significantly, Gerson translated Leonardo da Vinci's Treatise on Painting into Polish, making this seminal text accessible to Polish artists and students. He also authored an anatomy textbook for artists, Anatomia dla użytku artystów malarzy i rzeźbiarzy (Anatomy for the Use of Painters and Sculptors), further demonstrating his commitment to providing comprehensive artistic education.

Gerson was a co-founder and active member of the Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts (Towarzystwo Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych, often simply called Zachęta) in Warsaw, established in 1860. This organization played a vital role in supporting artists, organizing exhibitions, and acquiring artworks for its collection, effectively functioning as a national gallery in a city without one under state patronage. Gerson's involvement with Zachęta underscored his dedication to building artistic infrastructure and fostering a thriving art scene in Poland.

His diverse talents also led him to occasional work in other artistic fields. He undertook stage design for the Teatr Wielki (Grand Theatre) in Warsaw, and even engaged in architectural design, notably designing a bell tower for the church in Kunów in 1896. These activities highlight his broad artistic interests and his willingness to contribute his skills to various aspects of cultural production.

Artistic Connections and Contemporaries

Gerson's career unfolded within a rich network of artistic relationships. His teachers, from Piwarski in Warsaw to Cogniet in Paris, shaped his early development. His students, as detailed above, formed a veritable "who's who" of the next generation of Polish art, and their subsequent careers often showed a dialogue with, or a departure from, Gerson's Realist principles.

Among his contemporaries, Jan Matejko was the towering figure of historical painting, and their approaches, while both patriotic, offered different interpretations of the genre. The Gierymski brothers, Maksymilian and Aleksander, were fellow Realists who explored different facets of Polish life, with Maksymilian focusing on genre scenes often related to the January Uprising and Aleksander on urban Realism and later experiments with light. Henryk Rodakowski was another significant Polish painter of the era, known for his portraits and historical scenes, often with a more academic or Romantic leaning.

Gerson's engagement with the broader European art scene, particularly during his studies in Paris, connected him to international trends. While he remained firmly rooted in Polish themes and Realist aesthetics, his awareness of movements like Impressionism (which many of his students would embrace) informed his understanding of contemporary art, even if he did not adopt these styles himself. His work can be seen as part of a wider European Realist movement that included artists like Gustave Courbet in France, Ilya Repin in Russia, and Wilhelm Leibl in Germany, all of whom sought to depict the world around them with unflinching honesty.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Wojciech Gerson passed away in Warsaw on February 25, 1901. He left behind a rich legacy as one of Poland's most important 19th-century artists and a foundational figure of Polish Realism. His dedication to depicting the Polish landscape, history, and rural life contributed significantly to the visual articulation of Polish national identity during a period of foreign domination.

His influence as an educator was immense. The Warsaw School of Drawing under his guidance became a crucible for artistic talent, producing many of the artists who would lead Polish art into the 20th century and embrace movements such as Impressionism, Symbolism, and Art Nouveau (as part of the Young Poland movement). Artists like Stanisław Wyspiański, though not a direct student in the same way, were part of the artistic milieu that Gerson helped to shape.

Gerson's paintings are held in major Polish museums, including the National Museums in Warsaw, Krakow, and Poznań, and continue to be admired for their technical skill, historical significance, and evocative power. His landscapes, in particular, are celebrated for their pioneering role in establishing a national school of landscape painting. His writings and translations further enriched Polish artistic culture.

In a broader art historical context, Gerson represents a vital strand of 19th-century European Realism, adapted and infused with the specific concerns and aspirations of Polish national culture. He successfully balanced academic rigor with a commitment to truthful observation, creating an art that was both artistically accomplished and deeply meaningful to his compatriots.

Conclusion

Wojciech Gerson's life and work offer a compelling insight into the artistic and cultural landscape of 19th-century Poland. As a painter, he masterfully captured the essence of his homeland, from its majestic mountains to the daily lives of its people and the pivotal moments of its history. As an educator, he nurtured a generation of artists who would carry Polish art forward. As a critic and cultural activist, he tirelessly worked to elevate the standards and status of art in Poland. His unwavering commitment to Realism, combined with his profound patriotism and dedication to artistic education, secures his place as a pivotal and revered figure in the annals of Polish art history. His legacy endures not only in his own remarkable body of work but also in the achievements of the many artists he inspired.