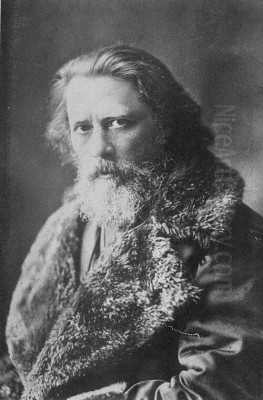

Mihály von Zichy stands as a fascinating and significant figure in 19th-century European art. A Hungarian by birth, his prodigious talent led him far beyond his homeland, most notably to the heart of the Russian Empire, where he served as a court painter for decades. Zichy was a versatile artist, excelling as a painter, a masterful graphic artist, and a prolific illustrator. His work embodies the spirit of Romanticism, characterized by dramatic intensity, emotional depth, and often, a meticulous attention to detail. Navigating the cultural landscapes of Hungary, Austria, Russia, and France, Zichy created a unique artistic legacy that bridged nations and artistic disciplines, leaving behind a rich body of work that continues to captivate audiences today.

Formative Years and Artistic Awakening

Mihály Zichy was born on October 15, 1827, in the village of Zala, located in Zala County, Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Austrian Empire. Born into the Hungarian nobility (the Zichy family), his path initially seemed destined for a more conventional career. He pursued legal studies in Budapest, a common trajectory for young men of his social standing. However, the pull towards art proved irresistible. During his time in Budapest, he simultaneously enrolled in Jakab Marastoni's art school, taking his first formal steps into the world of painting and drawing. Marastoni, an artist of Italian origin who settled in Hungary, provided Zichy with foundational training.

The artistic environment in Hungary during the 1840s was gradually developing its own national identity, looking towards historical themes and local landscapes, moving away from the dominant Viennese influence. Artists like Károly Markó the Elder were already established, known for their idealized landscapes. Zichy's early exposure to art in Budapest laid the groundwork, but his ambition soon led him to seek more advanced training in one of Europe's major artistic centers.

Recognizing his potential, Zichy moved to Vienna, the imperial capital, to study at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts. There, he became a pupil of Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, a leading Austrian painter known for his Biedermeier portraits, genre scenes, and landscapes, as well as his emphasis on the close study of nature. Waldmüller's rigorous approach and focus on realism likely honed Zichy's technical skills, particularly his draftsmanship and ability to capture likenesses and textures. This Viennese period was crucial in refining his abilities and exposing him to broader European artistic currents, setting the stage for his future international career.

The Call to Russia: A New Horizon

In 1847, a significant opportunity arose that would dramatically alter the course of Zichy's life and career. He received a recommendation from Waldmüller to take up a position in St. Petersburg, the glittering capital of the Russian Empire. His initial role was as an art teacher to the daughter of Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, a German-born princess who was an influential figure in Russian society and a notable patron of the arts. This appointment placed the young Hungarian artist directly within the orbit of the Russian imperial court.

His arrival in Russia coincided with a period of political ferment across Europe. The Revolutions of 1848, including the Hungarian Revolution seeking independence from the Habsburgs, created a tense atmosphere. Zichy's own liberal leanings and perhaps his perceived sympathies with the Hungarian cause reportedly led to some difficulties early on. It's suggested that his political views caused friction, potentially leading to a temporary dismissal from his teaching post. This early challenge highlighted the complexities of navigating court life and the political sensitivities of the era.

Despite this initial setback, Zichy's artistic talent could not be ignored. He remained in St. Petersburg, finding work as a retoucher for a photographer, a role that likely further sharpened his eye for detail and composition. He continued to paint and draw, gradually building his reputation within the city's artistic circles. Russia, at this time, had its own burgeoning art scene, with the Imperial Academy of Arts fostering a generation of painters, often focused on historical and mythological subjects in the academic style, such as Karl Bryullov, famous for his monumental The Last Day of Pompeii. Zichy's unique blend of Hungarian sensibility and Viennese training offered something distinct.

Chronicler of the Tsars: Life as Court Painter

Zichy's perseverance and undeniable skill eventually led to his formal appointment as court painter in 1859. This prestigious position marked the beginning of a long and remarkable period of service to the Russian Imperial family, spanning the reigns of several Tsars. While sometimes referred to as the "artist of four emperors," his most significant tenure covered the reigns of Alexander II, Alexander III, and the early years of Nicholas II. He became an intimate visual chronicler of the Romanov dynasty and the elaborate world they inhabited.

His duties were varied and demanding. Zichy was tasked with documenting the grand occasions and the more private moments of imperial life. He produced numerous watercolors and drawings capturing coronations, such as his detailed series depicting the coronation of Alexander II, state visits, diplomatic receptions, lavish court balls, imperial hunts (a favourite pastime of the Tsars), military reviews, and family celebrations like weddings and christenings. These works possess immense historical value, offering vivid glimpses into the rituals, fashions, and personalities of the Russian court.

Unlike strictly formal portraitists, Zichy often brought a sense of immediacy and dynamism to these scenes. His background in graphic arts informed his approach; he excelled at capturing fleeting moments, gestures, and the overall atmosphere of an event. While maintaining accuracy in depicting individuals and settings, his compositions often possess a lively quality, showcasing his skill in handling complex group scenes and architectural interiors. His work in this capacity can be compared to other European artists who documented court life, such as Franz Krüger at the Prussian court, though Zichy often employed a looser, more Romantic style. His service earned him recognition, including the Order of St. Stanislaus (Second Class).

The Romantic Vision: Style and Substance

Mihály Zichy was fundamentally an artist of the Romantic movement, which swept across Europe in the first half of the 19th century and continued to influence art for decades. His work embodies many key characteristics of Romanticism: a focus on emotion, individualism, drama, and often, an interest in history, literature, and the exotic. His style is marked by a powerful combination of technical proficiency and expressive intensity.

One of the hallmarks of Zichy's art is his exceptional draftsmanship. Whether in quick sketches, detailed illustrations, or finished paintings, his command of line is evident. He used line not just to define form but also to convey movement, energy, and emotion. This graphic sensibility is apparent even in his paintings, which often retain a strong linear quality beneath the layers of colour. His compositions are frequently dynamic, employing diagonal lines, swirling forms, and dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create visual excitement and emotional impact.

His subject matter ranged widely, reflecting the diverse interests of the Romantic era. He tackled historical events, religious themes, scenes from literature, and observations of contemporary life. Even in his court commissions, a Romantic sensibility often permeates the work, elevating documentary scenes beyond mere reportage. He was adept at capturing psychological states, whether the solemnity of a state occasion, the thrill of the hunt, or the intimate drama of a literary narrative. His work can be seen in dialogue with other great European Romantics like Eugène Delacroix in France, known for his passionate historical paintings, or even J.M.W. Turner in Britain, who captured the sublime power of nature and historical catastrophe with unparalleled energy.

Master of the Narrative: Zichy the Illustrator

Beyond his paintings and court duties, Mihály Zichy achieved significant fame as an illustrator. He possessed a remarkable ability to translate complex literary narratives and abstract concepts into compelling visual form. His illustrations were not mere decorations but profound interpretations that captured the spirit and drama of the texts he worked with. This aspect of his career cemented his reputation across Europe and remains one of his most celebrated contributions.

One of his most significant projects was illustrating the Georgian national epic, The Knight in the Panther's Skin, by Shota Rustaveli. Commissioned in the 1880s, Zichy produced a series of around 35 powerful illustrations that brought this medieval tale of chivalry, love, and friendship to life for a wider audience. His dynamic compositions and emotionally charged depictions resonated deeply and are still highly regarded in Georgia today, demonstrating his ability to engage with diverse cultural traditions.

In his native Hungary, Zichy undertook the monumental task of illustrating Imre Madách's philosophical drama, The Tragedy of Man (Az ember tragédiája). This complex work traces the journey of Adam and Eve through history, exploring themes of progress, disillusionment, and the human condition. Zichy's illustrations masterfully visualized the play's epic scope and allegorical depth, becoming almost inseparable from the text itself in the Hungarian cultural consciousness. He also illustrated the ballads of János Arany, another cornerstone of Hungarian literature, further solidifying his connection to his homeland's cultural heritage.

Zichy's talents as an illustrator also found expression with canonical works of world literature. He created widely admired illustrations for Goethe's Faust and for works associated with the legend of Don Juan. These illustrations, often characterized by their dramatic intensity and psychological insight, circulated widely and contributed significantly to his international renown. In the realm of illustration, his work invites comparison with contemporaries like the incredibly prolific Gustave Doré, whose dramatic engravings for works like Dante's Inferno and the Bible were immensely popular, though Zichy often brought a more fluid, painterly quality even to his graphic work. His deep engagement with literature echoes that of artists like William Blake, who created visionary interpretations of epic poems.

Spotlight on Masterpieces

Several key works stand out in Mihály Zichy's diverse oeuvre, showcasing his technical skill, thematic concerns, and Romantic sensibility. These paintings and graphic works encapsulate the different facets of his artistic personality, from historical allegory to social commentary and dramatic narrative.

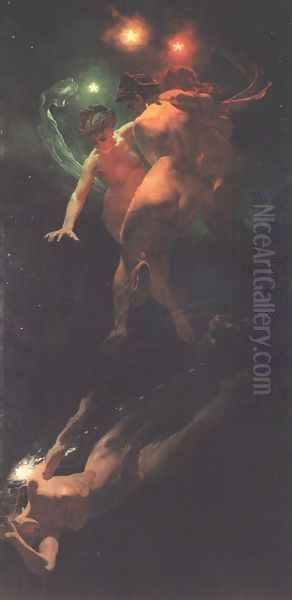

The Triumph of the Genius of Destruction (1878) is one of Zichy's most powerful and allegorical paintings. Created during his time away from Russia, likely in Paris, this large-scale work depicts a chaotic, dynamic scene where destructive forces seem to overwhelm creative or positive ones. The swirling composition, dramatic use of light and shadow, and emotionally charged figures create a sense of turmoil and unease. It has been interpreted as a commentary on war, perhaps reflecting on contemporary conflicts like the recent Franco-Prussian War or the ongoing Russo-Turkish War, or as a broader meditation on the darker aspects of human nature and progress. The painting's energy and thematic weight align it with the grand tradition of Romantic historical allegory seen in works by artists like Delacroix.

The Lifeboat (also known as Lifeboat) is another significant work, likely known through graphic versions. It depicts a dramatic scene of rescue or struggle at sea, a common theme in Romantic art that explored humanity's confrontation with the power of nature. Zichy captures the tension and desperation of the figures in the boat, battling the waves. The work emphasizes themes of survival, human vulnerability, and heroism. While perhaps not on the same scale, the theme echoes the harrowing intensity of Théodore Géricault's iconic Raft of the Medusa.

Zichy also tackled historical subjects with a darker edge, such as Auto-da-fé. This subject, depicting the public penance and executions carried out during the Spanish Inquisition, allowed Zichy to explore themes of religious fanaticism, power, and suffering. Such historical scenes, often imbued with a sense of drama and critique, connect Zichy to artists like Francisco Goya, who famously depicted the horrors of war and superstition. Other notable works, like Falling Stars and the historical genre scene The Drinking Orgy of Henry VIII, further demonstrate his range in subject matter and his ability to infuse historical or fantastical scenes with vivid life.

The Private World: Erotica and Intimacy

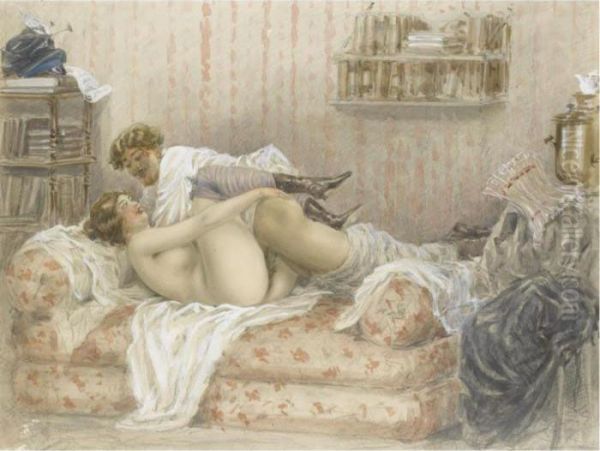

A distinct and often privately circulated aspect of Mihály Zichy's work is his engagement with erotic themes. While serving as a respected court painter and illustrator of grand narratives, Zichy also produced a considerable number of drawings and prints depicting scenes of intimacy, sensuality, and explicit sexuality. These works reveal a different side of the artist, one focused on the private, often hidden, aspects of human desire and relationships.

Many of these erotic works were compiled in a portfolio titled Liebe (Love), published in a limited edition, suggesting they were intended for a select audience of connoisseurs rather than public exhibition. The drawings display the same technical mastery evident in his other works – fluid lines, expressive figures, and a keen observation of human anatomy and emotion. They range from tender depictions of lovers to more explicit and sometimes unsettling scenes, exploring the complexities and ambiguities of human sexuality.

This aspect of his work was not entirely unique for the era; erotic art had a long history, and the 19th century saw a continued, often clandestine, interest in such themes. However, Zichy's approach was notable for its directness and psychological insight. His erotic drawings were known and appreciated by some contemporaries. The influential French writer and art critic Théophile Gautier, himself no stranger to sensual themes in literature, was a known admirer of Zichy's overall work, and likely appreciated this facet as well.

Interestingly, Zichy's erotic drawings found an admirer in a later generation's master: Vincent van Gogh. During his time in The Hague, Van Gogh encountered and copied some of Zichy's drawings, including those with erotic content. Van Gogh was drawn to Zichy's expressive line and his ability to capture raw human emotion, even in these intimate subjects. This connection underscores the reach and impact of Zichy's graphic work, extending even to artists outside his immediate circle and stylistic lineage.

Bridging Cultures: Zichy in Europe

While Zichy spent the majority of his career in Russia, he remained connected to the broader European art world and maintained strong ties to his Hungarian heritage. Between 1874 and 1881, he left Russia and spent significant time in Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. This period allowed him to immerse himself in the vibrant Parisian scene, engage with other artists, and exhibit his work to a French audience.

During his time in Paris, he reconnected with fellow Hungarian artist Mihály Munkácsy, who had achieved international stardom with his dramatic genre scenes and historical paintings. The two Mihálys represented the pinnacle of Hungarian artistic achievement on the international stage, albeit with different styles and career paths. Zichy's presence in Paris also brought him into contact with French artists and intellectuals. It was during this period that Théophile Gautier penned his high praise, calling Zichy one of the most remarkable artistic talents he had encountered since the Romantic surge of 1830. Such acclaim from a leading critic significantly boosted Zichy's European reputation.

His circle extended beyond visual artists. Sources suggest friendships and interactions with prominent composers like César Franck and Ambroise Thomas, indicating his integration into the wider cultural milieu of Paris. This period allowed him to absorb new influences, although his fundamental Romantic style remained his anchor. The Paris art scene was then witnessing the rise of Impressionism, a radical departure from the academic and Romantic traditions Zichy represented. While he did not adopt Impressionist techniques, his time in Paris undoubtedly broadened his horizons and reinforced his standing as a major European artist. He also continued to travel, maintaining connections in Vienna and making visits back to his homeland, Hungary, particularly to his estate in Zala.

Twilight of Romanticism: Later Years and Legacy

Mihály Zichy eventually returned to St. Petersburg in 1883, resuming his role in service to the Russian court under Tsar Alexander III and later Nicholas II. He continued to be a prolific artist, working on illustrations, paintings, and documenting court life. However, the artistic landscape was changing rapidly. Romanticism, the dominant style of his youth and maturity, was increasingly seen as old-fashioned by the late 19th century. Realism had taken firm root, particularly in Russia with the rise of the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement, led by figures like Ilya Repin, who focused on contemporary social issues and Russian history with a critical eye. In France, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism were charting entirely new territories.

Despite these shifting tides, Zichy remained largely true to his established style. He continued to work with remarkable energy well into his seventies. His long service to the Russian court provided a measure of stability, even as artistic fashions evolved. He remained a respected figure, valued for his skill and his unique historical record of imperial life. He passed away in St. Petersburg on February 28, 1906, at the age of 78, having spent over half a century in Russia.

Mihály von Zichy's legacy is multifaceted. In Russia, he is remembered primarily as the artist who captured the visual history of the late Romanov era with unparalleled detail and intimacy. His works remain invaluable resources for historians studying the period. In his native Hungary, he is celebrated as one of the nation's foremost Romantic artists, particularly admired for his powerful illustrations of national literature like The Tragedy of Man. The Zichy Mihály Iparművészeti Szakgimnázium (a school of applied arts) in Kaposvár bears his name, and a museum dedicated to him exists, preserving his memory.

Globally, Zichy stands as a master of Romantic expression, particularly in the graphic arts. His illustrations demonstrate a profound ability to engage with complex narratives, while his paintings showcase dramatic flair and technical brilliance. He was an artist who successfully navigated different cultural contexts, achieving prominence in both Hungary and Russia, and recognition across Europe. His work serves as a bridge between these cultures and as a testament to the enduring power of the Romantic imagination, even as the world moved towards Modernism. His art continues to be exhibited, as seen in a 2024 exhibition in Tbilisi focusing on his illustrations for The Knight in the Panther's Skin, ensuring his unique contribution to art history remains visible.

Conclusion

Mihály von Zichy was more than just a painter or an illustrator; he was a visual storyteller, a cultural conduit, and a keen observer of the human condition. From the fields of Zala to the opulent halls of the Winter Palace, his life and art traversed geographical and social boundaries. As a Hungarian nobleman who became the visual chronicler of the Russian Tsars, he occupied a unique position. His mastery of Romantic drama, combined with a sharp eye for detail and a profound engagement with literature, resulted in a body of work that is both historically significant and artistically compelling. Whether depicting the grandeur of imperial ceremony, the intimate struggles of literary heroes, or the complexities of human desire, Zichy's art resonates with an emotional intensity and technical virtuosity that confirms his status as a major figure of 19th-century European art. His legacy endures in the galleries, libraries, and cultural memory of the nations he touched.