John Augustus Atkinson stands as a notable figure in the annals of British art, particularly recognized for his skill as an engraver and painter, and for his insightful depictions of Russian culture during a pivotal era. His life and work bridge the artistic worlds of late 18th and early 19th century Russia and Britain, leaving behind a valuable visual record, especially of the former. Born in 1775, Atkinson's career unfolded across decades marked by significant social and political change, a context that subtly informs his diverse body of work. He passed away around 1833, concluding a life dedicated to artistic observation and creation.

Early Life and Russian Sojourn

Atkinson's formative artistic years were significantly shaped by his time spent in Russia. Around 1784, still a young boy, he traveled to St. Petersburg. This journey was pivotal, as he went to study and work under the guidance of his uncle, James Walker. Walker was not merely a relative but a distinguished figure in his own right, serving as an engraver and painter to the court of Empress Catherine the Great. This connection provided Atkinson with unparalleled access and training within the vibrant, albeit foreign, artistic environment of the Russian imperial capital.

Working in St. Petersburg for a considerable period, from approximately 1784 until 1801, Atkinson immersed himself in the local culture. His position, likely facilitated by Walker, allowed him to observe Russian society across various strata. This extended stay was crucial in developing his unique specialty: capturing the essence of Russian life, its people, their customs, and their daily activities through his art. The skills he honed in engraving and watercolour during this period laid the foundation for his most celebrated works.

Masterwork: A Picturesque Representation

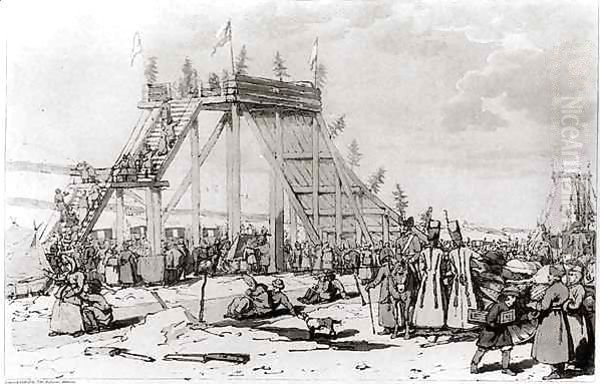

The culmination of Atkinson's years in Russia is undoubtedly his monumental work, A Picturesque Representation of the Manners, Customs and Amusements of the Russians. This ambitious project, undertaken in collaboration with James Walker, resulted in a significant folio work containing one hundred coloured plates. Published in three volumes between 1803 and 1804 after his return to London, it offered British and European audiences an unprecedented visual insight into the vast and relatively unknown Russian Empire.

Each plate in the series was meticulously crafted, showcasing Atkinson's keen eye for detail and his ability to render scenes with life and accuracy. The subjects ranged widely, covering everything from bustling city street scenes and peasant life in the countryside to courtly entertainments, religious processions, modes of transport like sleighs, and traditional costumes. The engravings were accompanied by descriptive texts in both English and French, further enhancing their ethnographic value and accessibility. This work cemented Atkinson's reputation as a skilled artist and an important visual ethnographer of Russia.

Return to England and Later Career

Upon returning to England around 1801, John Augustus Atkinson continued his artistic pursuits, integrating his experiences abroad into the British art scene. He settled in London and sought to establish himself among his peers. His talent, particularly in watercolour, gained recognition, leading to his election as a member of the prestigious Society of Painters in Water Colours in 1808. This affiliation placed him alongside prominent British watercolourists of the day, although the specific interactions are not detailed in the source material.

Atkinson also engaged with the broader London art world by exhibiting his works. He submitted pieces to the Royal Academy of Arts, a key venue for artists seeking patronage and critical notice. His participation in Royal Academy exhibitions spanned several years, with his final recorded contribution occurring in 1829. These exhibitions likely featured a mix of his Russian subjects and newer works perhaps reflecting British themes or historical events, showcasing his versatility beyond his well-known Russian portfolio. His continued activity demonstrates a sustained commitment to his artistic practice well into the 19th century.

Oil Paintings and Other Works

While renowned for his engravings and watercolours, particularly those in A Picturesque Representation, John Augustus Atkinson was also a capable oil painter. His subjects in this medium often mirrored the interests shown in his graphic work, encompassing military and historical scenes as well as further explorations of Russian life. Specific examples noted include portraits executed during his time in Russia, such as the `Portrait of Paul I` (1797), the `Portrait of Colonel N. P. Sheremetev` (1801), and the `Portrait of Alexander Z. Khitrovo` (1801). These portraits suggest a degree of access to notable figures within Russian society.

Later in his career, after returning to England, he continued to paint. A notable later oil painting is `Sliding Hills on the Neva` (1829), indicating his enduring interest in Russian themes even decades after leaving the country. Beyond painting and engraving, Atkinson also ventured into book illustration and potentially authorship. He is associated with the work The Miseries of Human Life (1807) and published a book titled A Set of Four in London in 1824, described as dealing with themes like poets, misers, polymaths, and melancholics, suggesting a satirical or humorous bent akin to contemporaries like Thomas Rowlandson.

Artistic Style and Themes

John Augustus Atkinson's artistic style is characterized by its detailed observation and representational clarity. Whether working in watercolour, oil, or engraving, he demonstrated a commitment to capturing the specifics of costume, setting, and human activity. His time in Russia fostered a deep understanding of the culture, which he translated into works that possess a strong ethnographic quality. He moved beyond mere exoticism to provide nuanced depictions of everyday life, social interactions, and cultural practices.

His focus on "manners, customs, and amusements" reveals an interest in genre scenes and the depiction of social fabric. This aligns him with a broader European tradition of artists documenting local life, but his specific focus on Russia, particularly for a British audience, was distinctive. His military and historical subjects, while less emphasized in the provided summary, suggest an engagement with the grander narratives and events of his time, possibly influenced by the Napoleonic Wars which formed a backdrop to much of his later career. His style aimed for accuracy and lively description, making his works valuable historical documents as well as artistic achievements.

Contemporaries and Collaborations

The most significant artistic relationship highlighted for John Augustus Atkinson is his collaboration with his uncle, James Walker. Walker, as court engraver in St. Petersburg, was not only a mentor but a direct partner in the creation of the Picturesque Representation series. This collaboration was fundamental to Atkinson's early success and specialization. While in Russia, he would have been aware of prominent Russian portraitists like Vladimir Borovikovsky and Dmitry Levitzky, whose careers overlapped with his stay, though direct interaction is not documented. The cityscape views of Fyodor Alekseyev also provide contemporary context for depictions of St. Petersburg.

Upon returning to London, Atkinson entered a vibrant art scene. As a member of the Society of Painters in Water Colours and an exhibitor at the Royal Academy, he was professionally associated with leading British artists. Figures like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable were dominant forces at the Academy exhibitions. In the realm of watercolour and social observation, artists such as Thomas Rowlandson and George Morland were contemporaries whose work sometimes shared thematic ground with Atkinson's interest in everyday life and social types. Historical painters like Benjamin West and Angelica Kauffman were influential figures at the Royal Academy during his exhibition years. Furthermore, the prevalence of engraving meant he worked in a field populated by skilled practitioners like Francesco Bartolozzi, although direct links are not specified.

Legacy and Collections

John Augustus Atkinson's primary legacy lies in his detailed and extensive visual record of Russian life at the turn of the 19th century. His Picturesque Representation remains a key resource for historians and cultural scholars studying the period. His work offered a unique window into a society that was undergoing significant change and was often perceived through stereotypes in Western Europe. He captured the diversity of the Russian Empire, from its imperial court to its peasantry, with a level of detail unusual for foreign artists of the time.

His works are preserved in various collections. Notably, a copy of his 1807 publication The Miseries of Human Life is held in the Rare Books and Manuscripts department of the Yale Center for British Art (under call number NC1475 .A85 1807), accessible to researchers by appointment. This indicates the scholarly interest his work continues to hold. Furthermore, his art has been featured in exhibitions, such as Of Green Leaf, Bird, and Flower, which took place at the Yale Center for British Art from May 15 to August 10, 2014. This inclusion demonstrates the enduring appeal and relevance of his contributions to British art and cultural history.

Distinguishing John Augustus Atkinson

It is important to clarify that the name "Atkinson" appears multiple times in historical records across various fields, and care must be taken to distinguish John Augustus Atkinson, the artist (1775-c.1833), from others sharing the surname. The provided source materials themselves highlight potential confusion by mentioning several other individuals named Atkinson involved in different activities.

For instance, the source mentions a John Atkinson or Joseph Atkinson noted as being unrelated to John Augustus Atkinson. It also references research on plagues in the ancient world (430 BC - 600 AD), attempting to find evidence of bubonic plague through textual analysis. While a John Atkinson is mentioned in connection with this research, it is highly unlikely to be the artist, given the subject matter and historical period focus. Similarly, mentions of chemistry research involving solution thermodynamics and laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy are linked to an Atkinson, but context suggests this is not the early 19th-century artist.

Further distinctions arise with John William Atkinson (often cited as J.W. Atkinson), a prominent 20th-century American psychologist known for his pioneering work on motivation, achievement, and behavior, including mathematical models and computer simulations. The source text links this figure to receiving an honorary professorship for contributions to motivation science and engaging in social activism, such as anti-Nixon protests in the 1960s. This is clearly a different individual from John Augustus Atkinson.

The source also brings up George Francis Atkinson, identified as a botanist specializing in mycology and plant pathology, known for work on Cryptogams and a monograph on North American Polyporaceae. Another figure, George Henry Atkinson, is mentioned in the context of public leadership in the Oregon territory, writing on railways, prisons, education, and agriculture. Lawrence Atkinson is noted as having joined the Vorticist movement, a 20th-century British art movement. Finally, Tony Atkinson (1944-2017, likely Sir Anthony Barnes Atkinson) is referenced as a renowned British economist focused on income inequality. None of these individuals should be confused with John Augustus Atkinson, the artist focused on Russian and British subjects in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Business and personal papers covering 1812-1840 related to family trade, land speculation, and investments are also mentioned in connection with an Atkinson family, but are not explicitly tied to John Augustus the artist in the source material provided.

Conclusion

John Augustus Atkinson carved a unique niche for himself in the art history of the late Georgian and Regency periods. His extensive work in Russia, particularly the creation of A Picturesque Representation of the Manners, Customs and Amusements of the Russians, stands as his most significant contribution, offering invaluable visual documentation of the Russian Empire at a time of limited firsthand accounts in the West. His skills in engraving and watercolour, combined with his keen observational abilities, allowed him to produce works that are both artistically accomplished and historically informative. Returning to England, he continued his career, participating in the London art world through societies and exhibitions. While perhaps overshadowed by some of his more famous contemporaries in British art like Turner or Constable, Atkinson's specialized focus and the quality of his output ensure his enduring importance, particularly as a cross-cultural visual chronicler. His work continues to be studied and appreciated in collections like the Yale Center for British Art, confirming his lasting legacy.