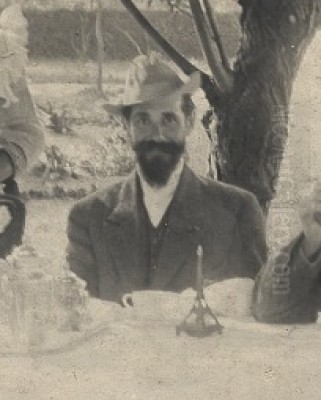

Myron G. Barlow (1873-1937) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in American art at the turn of the 20th century. An expatriate who spent a considerable portion of his productive life in France, Barlow cultivated a distinctive style characterized by its gentle introspection, nuanced color palettes, and a profound appreciation for the quiet moments of domestic life. His work, often featuring solitary female figures absorbed in thought or gentle activity, resonates with a dreamlike quality, drawing inspiration from Dutch Golden Age masters while subtly incorporating modern sensibilities. This exploration delves into the life, influences, artistic development, and legacy of Myron Barlow, an artist who bridged American artistic traditions with European experiences.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in America

Born in Ionia, Michigan, in 1873, Myron G. Barlow's formative years were spent in Detroit, a burgeoning industrial city that was also developing its cultural institutions. It was here that Barlow's artistic inclinations first took root. He pursued his initial art education at the Detroit Museum School, an institution that would later become part of the Detroit Institute of Arts, a museum that would eventually house some of his works. This early training provided him with the fundamental skills and exposure necessary for an aspiring artist of his time.

Seeking to further hone his craft, Barlow moved to Chicago to study at the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago. This institution, already a significant center for art education in the American Midwest, would have exposed him to a wider range of artistic styles and a more competitive academic environment. His time in Chicago was crucial in solidifying his commitment to an artistic career. Like many young artists of the period, Barlow's early professional endeavors included work as a newspaper artist. This practical experience, while perhaps not directly aligned with his fine art aspirations, would have sharpened his observational skills and ability to capture scenes quickly and effectively, traits that could subtly inform his later painting practice.

The Parisian Sojourn: Academic Training and New Influences

The allure of Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world, was irresistible for ambitious American artists. Barlow, following a well-trodden path, made his way to France to immerse himself in its rich artistic milieu. He enrolled at the esteemed École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic art training in Europe. There, he had the distinct privilege of studying under Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the most prominent academic painters of the 19th century. Gérôme, known for his meticulously detailed historical and Orientalist scenes, would have instilled in Barlow a rigorous approach to drawing, composition, and anatomical accuracy.

Studying under Gérôme placed Barlow within a lineage of academic tradition that emphasized technical mastery and narrative clarity. Artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau were also key figures in this academic sphere, producing highly finished works that were celebrated in the official Salons. However, Paris at this time was also a crucible of artistic revolution. The Impressionist movement, with pioneers like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas, had already challenged academic conventions, and Post-Impressionist artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Georges Seurat were pushing artistic boundaries even further. While Barlow's training was rooted in academicism, the vibrant, experimental atmosphere of Paris undoubtedly exposed him to these avant-garde currents, which would subtly filter into his evolving personal style.

The Vermeerian Epiphany and the Emergence of a Signature Style

A pivotal moment in Myron Barlow's artistic development occurred during a visit to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. It was there, while reportedly copying works by the Dutch Golden Age master Johannes Vermeer, that Barlow experienced a profound artistic awakening. Vermeer's serene interior scenes, his masterful handling of light, and his sensitive portrayal of women engaged in quiet domestic activities deeply resonated with Barlow. This encounter was transformative, steering him towards the themes and aesthetic qualities that would define his mature work.

Following this experience, Barlow began to concentrate on depicting female figures, often solitary, within intimate, dreamlike interior settings. His canvases became characterized by a subtle, often monochromatic color palette, with a particular fondness for varying shades of blue, which lent a cool, contemplative atmosphere to his paintings. This preference for a dominant hue, creating a harmonious and unified mood, became a hallmark of his style. While his compositions retained a sense of traditional structure, his brushwork and the overall sensibility of his paintings often hinted at more modern approaches, creating a unique tension between the classical and the contemporary. His work began to reflect a deep sensitivity to the inner lives of his subjects, capturing moments of quiet reflection and introspection. This focus on intimate, psychological portraiture set him apart from many of his contemporaries who might have been more engaged with grander historical themes or the fleeting impressions of outdoor light in the vein of Childe Hassam or Theodore Robinson in American Impressionism.

Life and Work in France: Trépied and Étaples

Barlow chose to live and work in France for a significant portion of his adult life, finding the environment conducive to his artistic pursuits. Around the turn of the century, circa 1900, he settled in the village of Trépied, in the Artois region of northern France, near the artists' colony of Étaples. He established a solitary existence there for over a decade, transforming a rustic farmhouse into his studio. This rural seclusion allowed him to focus intensely on his work, developing his personal vision away from the direct pressures of the Parisian art market. The poppy fields surrounding his Trépied studio often served as vibrant backdrops for his figure studies, where he would pose models, integrating the human form with the natural beauty of the French countryside.

His time in France was not without its challenges. During World War I, the Étaples area, where he also spent time, became a major Allied military base and hospital center. Barlow found himself compelled to remain in Étaples for four years during the conflict. His studio there was reportedly threatened on multiple occasions by German bombing raids, a stark reminder of the turmoil engulfing Europe. Despite these dangers, he continued to work, his art perhaps offering a refuge from the surrounding chaos. This extended period in France, particularly in Trépied, was crucial for the maturation of his style, allowing him to cultivate the dreamlike, introspective qualities that are so characteristic of his paintings. His expatriate experience mirrors that of other American artists like John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler, who also found Europe to be a fertile ground for their careers, though Barlow's focus remained more on intimate genre scenes than the society portraiture of Sargent or the aestheticism of Whistler.

Representative Works and Thematic Concerns

Myron Barlow's oeuvre is distinguished by its consistent thematic focus and stylistic coherence. Among his most representative works is A Quiet Moment; Knitting in the Garden (also referred to as A Moment of Quiet: Weaving in the Garden). This painting exemplifies his signature style, likely depicting a woman absorbed in a tranquil activity, set against a soft, atmospheric background. Such scenes highlight Barlow's ability to capture subtle emotional states and create a palpable sense of peace and introspection. The interplay of light, often soft and diffused, and the carefully chosen color harmonies contribute to the overall poetic mood of these works.

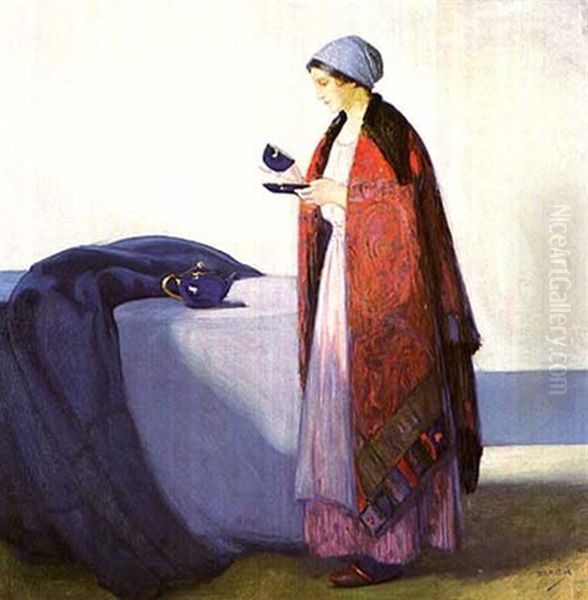

Another notable painting is A Cup of Tea, dated to 1922. This work, likely featuring a woman in an interior setting, perhaps pausing for refreshment, aligns with his interest in the quiet rituals of daily life. The year 1922 is also when Katherine Mansfield's famous short story "A Cup of Tea" was written, and while a direct connection is not established, the coincidence points to a shared cultural interest in exploring the nuances of social interactions and individual psychology through seemingly simple domestic scenes. Barlow's painting The Toilet, also part of his body of work, further underscores his focus on intimate, private moments in women's lives, a theme also explored by contemporaries like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, though often with different stylistic approaches. His figures are rarely overtly emotional; instead, they exude a gentle melancholy or serene contemplation, inviting the viewer to ponder their inner worlds.

Connections to Detroit and American Recognition

Despite spending much of his career in France, Myron Barlow maintained significant ties to his American roots, particularly to Detroit. He served as the president of the Detroit Scarab Club, an organization of artists and art lovers that played an important role in the city's cultural life. This leadership position indicates his respected standing within the Detroit art community. His commitment to the city was further demonstrated by his commission to create murals for the main hall of Detroit's Temple Beth El, a significant undertaking that would have brought his art to a wider public audience within his home city.

Barlow's work received considerable recognition in the United States and internationally. He was awarded a prestigious gold medal at the St. Louis World's Fair (Louisiana Purchase Exposition) in 1904, a major international event that showcased artistic and technological achievements. He received another gold medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, further cementing his reputation. His paintings were exhibited in various American galleries, including the Detroit Institute of Arts, which holds several of his pieces. His work was also collected by other American and French galleries, indicating a transatlantic appreciation for his unique artistic vision. He exhibited alongside other prominent American artists of his time, including landscape painter George Inness and H.A. Wyatt, though his primary focus remained distinct from the Barbizon-influenced landscapes of Inness or the specific styles of other contemporaries.

Barlow in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Myron Barlow's artistic contributions, it is useful to consider him within the broader context of his contemporaries. While his training under Jean-Léon Gérôme linked him to the academic tradition, his mature style diverged significantly from the highly polished, narrative-driven works of Gérôme or other academicians like Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who also specialized in historical and classical scenes. Barlow's art, with its emphasis on mood, suggestion, and intimate psychology, shared more in common with the Symbolist undercurrents of the late 19th century or the Intimist movement, which included artists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, though Barlow's aesthetic remained more rooted in figurative realism than the decorative patterning of the Nabis.

His deep admiration for Johannes Vermeer connected him to a lineage of artists fascinated by light and domestic interiors, a tradition also seen in the work of Dutch contemporaries of Vermeer like Pieter de Hooch. In the American context, while some of his expatriate peers like Mary Cassatt focused on themes of motherhood and modern women with a brighter, more Impressionistic palette, Barlow's work retained a more subdued, almost ethereal quality. He did not fully embrace the broken brushwork or plein-air principles of French Impressionists like Monet or Pissarro, nor the vibrant Fauvist colors that emerged in the early 20th century with artists like Henri Matisse. Instead, Barlow carved out a niche for himself, creating a body of work that was both personal and reflective of a certain romantic sensibility that persisted even amidst the rapid changes of modern art.

Artistic Style Revisited: Color, Light, and Atmosphere

The defining characteristics of Myron Barlow's art lie in his sophisticated use of color, his subtle manipulation of light, and the pervasive dreamlike atmosphere he created. His preference for a dominant color, often a cool blue, unified his compositions and imbued them with a specific emotional tone. This was not the vibrant, analytical use of color seen in Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat, but rather a more emotive and atmospheric application. The light in his paintings is rarely harsh or direct; instead, it is often diffused, filtering gently into interiors or softly illuminating figures in outdoor settings, reminiscent of the luminous qualities found in Vermeer's work.

This careful modulation of light and color contributed significantly to the introspective and often melancholic mood of his paintings. His figures, typically women, appear lost in thought, their expressions serene yet enigmatic. Barlow's technique, while grounded in academic draftsmanship, often featured a softness of form and a delicacy of touch that enhanced the ethereal quality of his scenes. He managed to blend traditional elements of representation with a more modern sensitivity to psychological nuance and atmospheric effect, creating a style that was uniquely his own. His works invite quiet contemplation, drawing the viewer into a world of subtle beauty and gentle introspection.

Legacy and Conclusion

Myron G. Barlow passed away in 1937, leaving behind a body of work that continues to charm and intrigue. While he may not have achieved the widespread fame of some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, his contribution to American art, particularly within the realm of figurative painting and intimate genre scenes, is undeniable. He successfully synthesized his American artistic education with his European experiences, particularly his deep engagement with French culture and his admiration for Dutch masters. His paintings, with their characteristic blue tonalities, dreamlike atmospheres, and sensitive portrayals of women in moments of quietude, offer a unique window into the artistic sensibilities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

His dedication to his personal vision, developed in the relative seclusion of his French studios, allowed him to create art that was both timeless and deeply personal. The recognition he received through awards and acquisitions by significant museums attests to the quality and appeal of his work during his lifetime. Today, Myron Barlow is remembered as an artist who skillfully captured the subtle poetry of everyday life, creating a world of quiet beauty and introspection that continues to resonate with viewers. His legacy is that of a dedicated craftsman and a sensitive observer of the human spirit, an American artist who found his distinctive voice between two continents. His paintings remain as testaments to the enduring power of art to convey nuanced emotion and to celebrate the quiet, often overlooked, moments of human experience.