Gwendolen Mary John, known to the art world as Gwen John, stands as a unique and compelling figure in early twentieth-century European art. A Welsh painter who spent most of her productive life in France, she cultivated a distinct artistic voice characterized by quiet intensity, subtle emotional depth, and a profoundly introspective gaze. While often overshadowed during her lifetime by her more flamboyant brother, the painter Augustus John, Gwen John's reputation has steadily grown since her death. Today, she is recognized not only as a significant Welsh artist but as a key contributor to the currents of modernism, admired for her technical mastery, her focused subject matter, and the serene yet potent atmosphere of her work. Her life, marked by intense relationships, deep religious faith, and a commitment to artistic solitude, is as fascinating as the canvases she produced.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Wales and London

Gwendolen Mary John was born on June 22, 1876, in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, Wales. She was the second of four children born to Edwin William John, a solicitor, and his wife, Augusta Smith. Her mother, an amateur watercolourist, fostered an early interest in art among her children, including Gwen's younger brother, Augustus, who would also become a famous painter, and her elder brother Thornton and younger sister Winifred. The family environment, though outwardly conventional, contained seeds of artistic inclination.

Following Augusta John's death in 1884, the family moved to the coastal town of Tenby, also in Pembrokeshire. It was here that Gwen and Augustus began to seriously develop their artistic talents, sketching and drawing the landscape and local people. Their shared passion for art created a close bond, though their artistic temperaments and eventual styles would diverge significantly.

In 1895, Gwen John followed her brother Augustus to London to study at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art, then part of University College London. The Slade was notable for being one of the few art institutions in Britain at the time that admitted female students on relatively equal terms with men. This period, lasting until 1898, was crucial for her technical development. She studied under influential figures like Frederick Brown and Henry Tonks, known for their emphasis on rigorous draughtsmanship. John excelled, particularly in figure studies, winning the Nettleship Prize for Figure Composition in her final year. Despite this recognition, some contemporary accounts noted a perceived lack of bold "personality" in her work, perhaps reflecting the prevailing biases against the quieter, more introspective styles often pursued by female artists of the era. Her time at the Slade solidified her technical foundation and exposed her to a network of fellow artists, shaping her early artistic identity.

The Parisian Experience: Whistler, Rodin, and the Avant-Garde

Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world at the turn of the twentieth century, beckoned Gwen John. She first visited in 1898, briefly studying at the Académie Carmen under James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Whistler's emphasis on tonal harmony and atmospheric subtlety likely resonated with John's own developing aesthetic sensibilities, offering an alternative to the more academic training of the Slade. Though her time at Whistler's academy was short, his influence can be discerned in the refined palettes and quiet moods of her later work.

A more definitive move occurred in 1904. After a period back in London, John, accompanied by fellow artist and model Dorelia McNeill (who would later become Augustus John's partner), embarked on an adventurous walking tour intending to reach Rome, though they ultimately settled in France. John established herself in Paris, initially supporting herself by working as an artist's model. This move placed her firmly within the vibrant, experimental milieu of Montparnasse and the Latin Quarter.

It was during this period, specifically in 1904, that she met the towering figure of French sculpture, Auguste Rodin. Seeking work as a model, she was introduced to the aging but still immensely influential artist. This meeting sparked an intense and complex relationship that would last for over a decade. John became not only one of Rodin's models (notably for his monument to Whistler and several intimate drawings) but also his lover. Their passionate affair, documented in thousands of letters primarily from John to Rodin, was marked by her deep devotion and emotional dependency, and his alternating encouragement and distance. This relationship profoundly impacted John's emotional life and, arguably, her art, providing both inspiration and turmoil. Rodin recognized her talent, purchasing some of her works and offering encouragement.

Living and working in Paris brought John into contact with the leading figures of the avant-garde. While she maintained a degree of personal reserve, she moved within circles that included artists like Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Braque, who were revolutionizing painting. She also knew the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who served for a time as Rodin's secretary, and the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, another figure associated with Rodin. Though not directly aligned with Cubism or Fauvism, John absorbed the atmosphere of artistic innovation, refining her own unique modernist language amidst this ferment.

Artistic Style and Themes: The Quiet Gaze

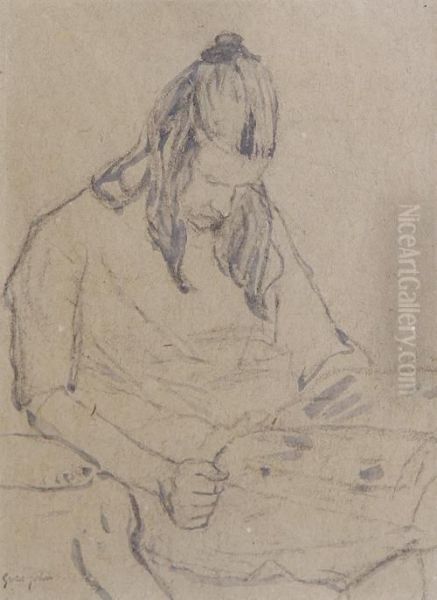

Gwen John's artistic style is characterized by its restraint, subtlety, and profound psychological depth. She focused primarily on a limited range of subjects: portraits, predominantly of women and girls, seated figures in quiet interiors, studies of her beloved cats, and occasional still lifes and landscapes. Her approach was meticulous and deeply considered, often involving numerous preparatory drawings and studies for a single finished painting.

Her portraits are rarely dramatic or overtly expressive in the conventional sense. Instead, they convey a sense of stillness, concentration, and inner life. Her sitters, often depicted three-quarter length, gaze out with a quiet intensity or seem lost in thought. John favoured anonymous or little-known models, often young women or nuns, capturing their presence with empathy and respect. She returned to the same subjects repeatedly, exploring subtle variations in pose, light, and mood. This repetitive practice suggests an almost meditative approach, seeking to distill the essence of her subject through sustained observation.

John's use of colour is distinctive. She employed a muted palette, dominated by greys, creams, pale pinks, ochres, and soft blues and greens. These colours were applied with a technique that often involved dry, chalky paint layered onto carefully prepared grounds, sometimes canvas but frequently board or textured paper. This method contributed to the matte surface and subtle tonal gradations that are hallmarks of her work. The effect is one of harmony and quietude, where colour serves emotional resonance rather than descriptive accuracy alone. Comparisons can be drawn to the tonalism of Whistler, the intimate domesticity of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, or the quiet melancholy found in the interiors of Vilhelm Hammershøi.

Her interior scenes often depict simple corners of rooms, sparsely furnished, with light filtering through a window. These spaces are rendered with the same sensitivity as her portraits, becoming environments imbued with mood and feeling. They evoke solitude, contemplation, and the passage of time. Similarly, her numerous drawings and paintings of cats capture their characteristic poses and enigmatic presence with unsentimental affection, integrating them seamlessly into her world of quiet observation.

While influenced by Post-Impressionism in her brushwork and attention to formal structure, John forged a path distinct from the bolder experiments of many contemporaries. Her modernism lies not in radical formal distortion but in the intensity of her psychological focus and the refinement of her technique to express subtle states of being. Her work stands in stark contrast to the more extroverted and colourful style of her brother, Augustus John, highlighting their divergent artistic paths despite their shared origins.

Key Works and Series

Several works and series stand out in Gwen John's oeuvre, encapsulating her unique vision and technical skill. Her Self-Portrait of circa 1900 (Tate, London) is a remarkable early statement. Painted while still in her twenties, it presents a direct, almost challenging gaze. The handling is confident, the palette restrained, and the composition strong. Art historians have noted its affinities with Old Master portraiture, particularly the self-portraits of Rembrandt, suggesting John's awareness of art history and her ambition to place herself within that tradition, albeit with a distinctly modern sensibility.

Her portraits of Dorelia McNeill, such as Dorelia in a Black Dress (c. 1903-04, Tate), showcase her ability to capture personality through subtle means. The pose is simple, the setting undefined, focusing attention entirely on the sitter's presence and enigmatic expression. These early portraits demonstrate the core elements of her mature style already taking shape.

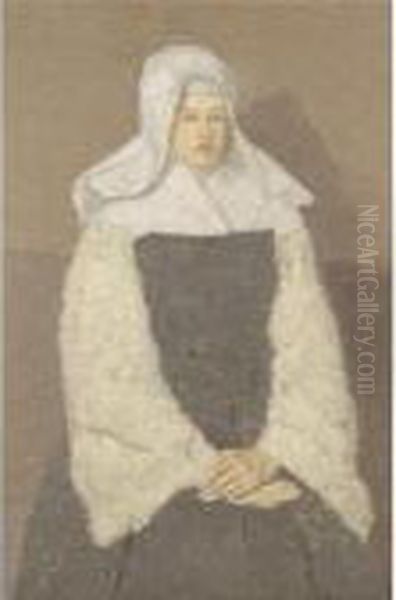

Perhaps her most famous series comprises the numerous portraits of Mère Marie Poussepin (Thérèse-Adèle Poussepin), the founder of the Dominican Sisters of Charity of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin. Commissioned around 1913 by the convent in Meudon where John eventually settled, these portraits were based on an existing prayer card. John produced dozens of versions in oil and watercolour over several years, exploring variations in colour, tone, and detail. This repetitive process, far from being mechanical, allowed her to delve deeply into the representation of piety and quiet strength, reflecting her own growing religious devotion. The Mère Poussepin series exemplifies her meticulous working method and her fascination with capturing subtle nuances through seriality.

Her depictions of anonymous young women, often titled Young Woman Holding a Black Cat (e.g., c. 1920-25, Tate) or simply Girl Reading, are quintessential Gwen John. These works combine her interest in female subjects, domestic interiors, and the quiet companionship of animals. The figures are absorbed in their own world, rendered with a characteristic blend of tenderness and reserve.

John's interior scenes, like A Corner of the Artist's Room in Paris (c. 1907-09, Museums Sheffield), demonstrate her mastery of light and atmosphere. Using a limited palette and simplified forms, she transforms mundane spaces into zones of contemplation. The careful arrangement of objects, the play of light on walls and floors, and the overall sense of stillness contribute to the profound emotional resonance of these works.

Later works, such as the landscape Two Houses in a Landscape (1930s), show a continuation of her restrained palette and simplified forms, applied to the external world. Even in landscape, her focus remains on mood and structure rather than topographical detail. Throughout her career, whether depicting people, animals, or spaces, Gwen John maintained a consistent vision focused on capturing the essence of her subjects through quiet observation and technical refinement.

Faith and Seclusion: The Later Years

A significant turning point in Gwen John's life and art was her conversion to Roman Catholicism around 1913. This decision appears to have been deeply personal and provided her with spiritual solace and a framework for her introspective nature. Her faith found direct expression in her art, most notably in the Mère Poussepin portraits and numerous drawings of nuns and worshippers at the Meudon convent. Religion seemed to reinforce her inclination towards a quiet, contemplative life dedicated to her art, which she increasingly viewed as a form of private devotion.

In 1911, she had moved from Paris to Meudon, a suburb southwest of the city. This move marked a gradual withdrawal from the bustling art scene and the beginning of a more reclusive existence. Her intense relationship with Rodin had cooled by this time (he died in 1917), and while she maintained some friendships, her primary focus became her work and her faith. She lived in rented rooms, often sparsely furnished, accompanied mainly by her cats. Her letters from this period reveal an intense inner life, marked by spiritual searching, anxieties about her work, and a profound need for solitude.

Her artistic practice became even more meticulous and slow-paced. She worked on paintings for years, layering thin washes of paint, constantly refining the tones and forms. She was notoriously reluctant to part with her work or exhibit frequently, describing her art in one letter as akin to "keeping a diary." This reluctance contributed to her relative obscurity during her lifetime compared to more publicly engaged artists.

Financially, John often struggled. For a period, she received crucial support from the American lawyer and art collector John Quinn, a major patron of modern art who also collected works by Picasso, Brancusi, Matisse, and writers like James Joyce and T.S. Eliot. Quinn purchased a significant number of John's works between 1910 and his death in 1924. His patronage provided vital income, but his death left her in a precarious financial position during her later years.

Despite her reclusiveness, she continued to paint and draw with dedication. Her health, however, began to decline in the late 1930s. In the summer of 1939, feeling unwell, she travelled to the coastal town of Dieppe in Normandy, possibly intending to cross to England. She collapsed upon arrival and was admitted to the Hôpital Saint-Jacques. Gwen John died there on September 18, 1939, at the age of 63. Having made a will leaving her possessions to her nephew, Edwin John, she was buried in an unmarked communal grave (a pauper's grave) in the Janval Cemetery in Dieppe. The exact location was later identified, and a simple gravestone now marks her resting place.

Legacy and Reappraisal

During her lifetime, Gwen John's reputation remained modest, particularly when compared to the international fame of her brother, Augustus John. Her quiet, introspective style, her limited range of subjects, and her reluctance to exhibit or promote her work meant she was known primarily within a small circle of artists, collectors like John Quinn, and critics. Augustus himself recognized her talent, famously stating after her death, "Fifty years after my death, I shall be remembered as Gwen John's brother." While perhaps an exaggeration at the time, his comment proved prophetic regarding the trajectory of their respective critical fortunes.

The process of reappraising Gwen John's work began shortly after her death. A memorial exhibition was held in London in 1946, organized by the Arts Council of Great Britain. This, along with subsequent exhibitions and critical attention, gradually brought her unique achievement into sharper focus. Critics began to appreciate the subtle power and psychological depth of her paintings, recognizing her mastery of tone and composition.

The rise of feminist art history in the 1970s and 1980s played a significant role in elevating John's status. Scholars seeking to recover the contributions of overlooked female artists found in Gwen John a compelling figure – a woman who forged a distinct artistic path in a male-dominated art world. Her focus on female subjects and interiority resonated with feminist concerns about representing women's experiences. She was increasingly discussed alongside other important female modernists like Paula Modersohn-Becker, Berthe Morisot, and Mary Cassatt, artists who navigated similar challenges in asserting their artistic identities.

Today, Gwen John is widely regarded as one of the most important British (and specifically Welsh) artists of the early twentieth century. Her work is admired for its quiet intensity, its technical refinement, and its unique blend of traditional observation and modern sensibility. While her output was relatively small compared to prolific contemporaries, the consistency and quality of her vision are undeniable. Her paintings and drawings are held in major public collections worldwide, including Tate Britain in London, the National Museum Wales in Cardiff, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Her influence can perhaps be seen less in direct stylistic imitation and more in the enduring appeal of quiet, observational painting that explores psychological depth. Artists drawn to stillness, subtle tonality, and intense scrutiny, such as perhaps the early work of Lucian Freud or the measured compositions of Euan Uglow, might be seen as sharing certain sensibilities. Ultimately, Gwen John's legacy rests on the singular power of her intimate, concentrated works, which continue to captivate viewers with their serene surfaces and profound emotional undercurrents.

Conclusion

Gwen John's art offers a window into a world of quiet contemplation and intense inner feeling. Through her meticulously crafted portraits, interiors, and studies, she explored the nuances of solitude, piety, and the subtle presence of her subjects. A Welsh artist who found her voice in the artistic crucible of Paris, she navigated complex personal relationships and deep religious faith while maintaining an unwavering dedication to her unique artistic vision. Though recognition came slowly, her achievement is now fully acknowledged. Gwen John stands as a master of understated expression, an artist who demonstrated that profound emotional depth could be conveyed through the quietest of means. Her intimate canvases continue to resonate, offering moments of stillness and profound connection in a noisy world, securing her place as a distinct and enduring figure in the landscape of modern art.