Niccolò Cannicci stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century Italian art. Born in Florence in 1846 and passing away in the same city in 1906, his life and career spanned a period of profound artistic and social transformation in Italy. As a prominent member of the second generation of Macchiaioli painters, Cannicci carved out a distinct niche for himself, celebrated for his sensitive portrayals of Tuscan rural life, his mastery of light, and his ability to imbue everyday scenes with a quiet, poetic dignity. His journey from academic training to a more personal, light-infused realism reflects the broader currents of European art, yet remains deeply rooted in the Tuscan soil he so lovingly depicted.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Niccolò Cannicci's artistic journey began under the initial tutelage of his father, Gaetano Cannicci, himself a painter. This early exposure to the world of art undoubtedly shaped his inclinations. His formal education commenced at the prestigious Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence, a city that was, and remains, a crucible of artistic heritage and innovation. At the Accademia, he studied under figures like Enrico Pollastrini, a painter known for his historical and allegorical subjects, executed with academic precision. He also briefly attended classes by a certain Marubini before gravitating towards the teachings of Antonio Ciseri (often cited as Antonio Cosenia in some records, though Ciseri is the more historically recognized figure associated with the Accademia at that time), who was respected for his religious paintings and portraits, combining academic skill with a degree of naturalism.

This academic grounding provided Cannicci with a solid technical foundation. However, like many of his contemporaries across Europe, he would soon find the strictures of academic art insufficient to express his evolving artistic vision. The mid-19th century was a period of artistic rebellion, with movements like Realism in France, led by Gustave Courbet, challenging the idealized and often anachronistic subject matter favored by the academies. Italy was no exception to this ferment, and Florence, in particular, became a hub for artists seeking new modes of expression.

The Macchiaioli: A Revolution in Italian Painting

Cannicci came to be closely associated with the Macchiaioli, a group of painters who, from around the 1850s and 1860s, radically departed from academic conventions. The term "Macchiaioli" (roughly translatable as "spot-makers" or "patch-painters") was initially a derogatory label applied by a critic, but the artists embraced it. They sought to capture the immediate reality of their surroundings, emphasizing the effects of light and shadow through broad, distinct patches ("macchie") of color, often applied directly from nature, or "en plein air."

The Macchiaioli were, in many ways, Italian counterparts to the French Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet, who also championed direct observation of nature and rural life. Key figures of the first generation of Macchiaioli, who established the movement's core tenets, included Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega, and Telemaco Signorini. These artists often gathered at the Caffè Michelangiolo in Florence to discuss art, politics, and their shared desire for a renewal of Italian painting, aligning with the patriotic fervor of the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification. Other notable painters associated with this foundational group include Odoardo Borrani, Raffaello Sernesi, and Vincenzo Cabianca.

Niccolò Cannicci, belonging to the second generation, inherited this legacy. While the initial revolutionary zeal might have tempered slightly, the commitment to truthfulness in representation, the focus on light, and the preference for everyday subjects, particularly rural landscapes and peasant life, remained central. Cannicci absorbed these principles, developing a style that, while clearly indebted to Macchiaioli techniques, also possessed a unique lyrical and introspective quality.

Artistic Style: Capturing Light and Rural Poetry

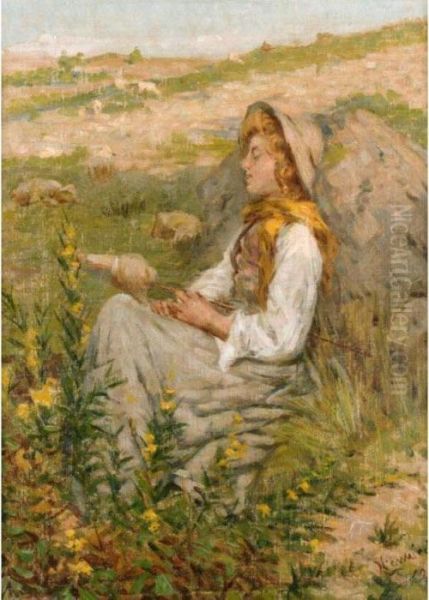

Cannicci's art is primarily characterized by its focus on landscape and genre scenes, particularly those depicting the Tuscan countryside and its inhabitants. He had a profound ability to capture the interplay of light and atmosphere, rendering the sun-drenched fields, dusty roads, and shaded groves of Tuscany with remarkable sensitivity. His style can be seen as a blend of Realism, in its honest depiction of rural labor and life, and an approach to light and color that shares affinities with Impressionism, though he maintained a stronger sense of form and structure than many of his French Impressionist contemporaries like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro.

His paintings often explore the liminal spaces where the city meets the countryside, or where cultivated fields give way to wilder nature. He was particularly adept at portraying figures within these landscapes – peasants at work, children at play, or solitary individuals lost in thought. These figures are never mere accessories; they are integral to the scene, their presence imbuing the landscapes with human warmth and narrative potential. His palette, especially in his mature works, tended towards harmonious, often muted tones, but he could also employ brighter, more luminous colors to convey the brilliance of Italian sunlight.

A distinctive feature of Cannicci's work is its underlying poetic sentiment. He avoided the overt social commentary found in the work of some Realists, instead focusing on the quiet dignity of rural existence and the timeless beauty of the natural world. There is a sense of tranquility, almost a gentle melancholy, that pervades many of his canvases, inviting contemplation rather than demanding immediate reaction.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

Throughout his career, Niccolò Cannicci produced a body of work that consistently explored his favored themes. One of his most celebrated paintings is "Le spigolatrici" (The Gleaners), exhibited in 1893 at the Società di Belle Arti in Florence, where it received an award. This work, depicting women gathering leftover grain after the harvest, is a classic example of his ability to ennoble a scene of humble labor, echoing the themes explored by Millet in France but with a distinctly Italian sensibility and light.

Another significant work often cited is "Ritorno dai campi" (Return from the Fields). This painting likely captures a common scene in the Tuscan countryside: workers heading home after a day's labor, perhaps silhouetted against the fading light. Such themes allowed Cannicci to explore the rhythms of rural life and the deep connection between the people and the land.

"Il girotondo" (The Round Dance) suggests a focus on childhood and innocence, a recurring motif in his oeuvre. Scenes of children playing in sunlit fields or village squares offered opportunities to depict uninhibited movement and the pure joy of simple pleasures, often bathed in a warm, inviting light.

His landscapes of the Maremma region of Tuscany and the area around San Gimignano were also highly regarded. These works, showcased, for instance, at the III Esposizione Internazionale d'Arte di Venezia (Venice Biennale) in 1899, demonstrate his continued engagement with the Tuscan landscape, capturing its unique character and atmosphere. The Maremma, with its rugged beauty and historical resonance, provided a rich source of inspiration.

While predominantly known for his landscapes and genre scenes, Cannicci also undertook some religious commissions, including frescoes depicting scenes from Dante Alighieri's "Divine Comedy." This indicates a versatility and a grounding in the grand traditions of Italian art, even as his primary focus lay in more contemporary and personal expressions.

Influences, Travels, and Artistic Connections

Cannicci's artistic development was shaped not only by his Italian peers but also by broader European trends. The influence of French art was particularly significant. A pivotal moment in his career was a trip to Paris in 1875, undertaken with fellow artists Francesco Gioli, Giovanni Fattori (a leading Macchiaiolo), and Egisto Ferroni. Paris at this time was the epicenter of the Impressionist revolution. Artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro were challenging artistic conventions with their radical approaches to light, color, and subject matter.

Exposure to French Impressionism undoubtedly reinforced Cannicci's own interest in capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. While he did not fully adopt the broken brushwork or the purely optical concerns of the Impressionists, their emphasis on outdoor painting and contemporary life resonated with the Macchiaioli ethos and likely encouraged a greater freedom in his own use of color and handling of paint. The influence of earlier French masters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, with his poetic landscapes, and Gustave Courbet, the standard-bearer of Realism, can also be discerned in the broader context of the Macchiaioli and, by extension, in Cannicci's work. Some art historians also note potential influences from artists like Gustave Caillebotte, whose structured compositions and urban scenes offered a different facet of modern life.

Back in Italy, Cannicci remained an active participant in the artistic life of Florence and beyond. He exhibited regularly, not only in Italy (Florence, Turin, Venice) but also internationally, with showings in cities like Paris and London. These exhibitions helped to establish his reputation and brought his work to a wider audience. His connections with fellow Macchiaioli like Fattori, Lega, and Signorini, as well as other contemporaries, fostered a supportive and intellectually stimulating environment. These artists, while individual in their styles, shared a common goal of creating an art that was modern, authentically Italian, and true to their lived experience.

Later Years, Stylistic Evolution, and Personal Challenges

The later part of Niccolò Cannicci's career was marked by both continued artistic production and personal challenges. In 1891, he experienced a period of mental health difficulties that led to a temporary interruption in his work and a stay in a hospital. Such personal trials can profoundly impact an artist's vision and output. Following his recovery, Cannicci returned to painting, and some observers note a shift in his style during this later period. His palette reportedly became somewhat brighter and his colors more luminous, perhaps reflecting a renewed engagement with the visual world or a deeper introspective turn.

Despite these challenges, he continued to create and exhibit. His participation in the 1899 Venice Biennale with his Maremma and San Gimignano landscapes demonstrates his ongoing commitment to his art. The themes of rural life and the Tuscan landscape remained central to his work, but his later paintings may carry an even deeper sense of personal reflection and a more solitary exploration of his subjects. This introspective quality, a hallmark of his art throughout his career, perhaps became more pronounced in his later years.

His dedication to capturing the essence of his native region, filtered through his unique sensibility, never wavered. He continued to find inspiration in the familiar scenes of Tuscany, transforming them into timeless images of beauty and quiet contemplation.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Niccolò Cannicci passed away in Florence in 1906, leaving behind a significant body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical skill, its poetic sensitivity, and its authentic portrayal of Tuscan life. His paintings are held in numerous public and private collections, both in Italy and internationally, including the Galleria d'Arte Moderna in Florence, which houses a significant collection of Macchiaioli art.

As a key figure of the second generation of Macchiaioli, Cannicci played an important role in consolidating and evolving the movement's achievements. He successfully bridged the Macchiaioli's commitment to realism and "macchia" technique with a more personal, lyrical approach to landscape and genre painting. His work stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of the Tuscan countryside and the dignity of its people.

While perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his French Impressionist contemporaries or even the first-generation Macchiaioli leaders like Fattori, Cannicci's contribution to Italian art is undeniable. He offered a nuanced and deeply felt vision of his world, capturing not just its outward appearance but also its underlying emotional and poetic resonance. His paintings invite viewers to slow down, to observe closely, and to appreciate the subtle beauty of the everyday. In an art world often dominated by grand gestures and radical innovations, Niccolò Cannicci's quiet, contemplative art offers a refreshing and enduring alternative, a gentle voice that continues to speak eloquently of the timeless connection between humanity and the natural world. His legacy is that of an artist who, with honesty and profound affection, painted the soul of Tuscany.