Oreste Costa (1851–1901) was an Italian painter who carved a distinct niche for himself in the vibrant art world of the late nineteenth century. While perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his contemporaries, Costa's dedication to the genre of still life, particularly his evocative depictions of game and the natural world, marks him as a significant figure in Italian art of the period. His work, characterized by meticulous detail and a profound understanding of his subject matter, offers a fascinating window into the artistic currents and tastes of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Born in 1851, Oreste Costa's artistic journey began in Florence, a city steeped in centuries of unparalleled artistic heritage. Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance, continued to be a vital center for artistic training and production in the 19th century. It was here that Costa received his formal art education, attending the prestigious Accademia di Belle Arti (Academy of Fine Arts). This institution was a cornerstone of artistic learning in Italy, upholding traditions of rigorous training in drawing, composition, and painting techniques.

The Florence of Costa's youth was an environment buzzing with artistic debate and innovation, even as it revered its past masters. The influence of the Macchiaioli movement, which had emerged in the 1850s and 1860s with artists like Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega, and Telemaco Signorini, was still palpable. These painters, with their emphasis on capturing the effects of light and shadow through "macchie" (patches or spots) of color and their commitment to realism and painting en plein air, had challenged academic conventions. While Costa's own style would develop differently, the prevailing atmosphere of artistic inquiry in Florence undoubtedly shaped his formative years.

The Tutelage of Antonio Ciseri

A pivotal aspect of Oreste Costa's artistic development was his studentship under Antonio Ciseri (1821–1891). Ciseri, a Swiss-Italian painter, was a highly respected figure in the Florentine art scene, known primarily for his religious paintings, which were executed with remarkable technical skill and a profound sense of drama. Born in Ronco sopra Ascona, Switzerland, Ciseri moved to Florence in 1833 to study at the Accademia di Belle Arti under Pietro Benvenuti and later Giuseppe Bezzuoli, both leading exponents of Neoclassicism and Romanticism.

Ciseri himself became an influential teacher at the Accademia. His style was characterized by a meticulous realism, often compared to photography in its precision, combined with a compositional clarity reminiscent of Renaissance masters like Raphael. Works such as "The Martyrdom of the Maccabees" (1863) and "Ecce Homo" (1871) showcase his mastery of anatomy, drapery, and emotional expression. Ciseri's emphasis on careful observation, detailed rendering, and a polished finish would have been key components of his teaching.

Under Ciseri, Oreste Costa would have honed his technical abilities and absorbed the principles of academic painting. Other notable artists who studied with Ciseri included Giuseppe Guzzardi (1845-1914), known for his portraits and genre scenes. The discipline and attention to detail instilled by Ciseri are evident in Costa's subsequent specialization in still life, a genre that demands precision and a keen eye.

Specialization in "Natura Morta"

Oreste Costa became particularly renowned for his "natura morta," the Italian term for still life. More specifically, he excelled in a subgenre often referred to as "morte della natura" (death of nature), which typically involved depictions of hunted game – birds, rabbits, and other animals – often arranged with hunting paraphernalia. This theme was popular in European art, with a long tradition stretching back to 17th-century Dutch and Flemish masters like Jan Weenix or Frans Snyders, and continuing with artists like Jean-Baptiste Oudry and Jean-Siméon Chardin in 18th-century France.

Costa's choice of subject matter resonated with the tastes of the burgeoning bourgeoisie and aristocracy, who often engaged in hunting as a leisure activity. These paintings were not merely decorative; they could symbolize wealth, the bounty of nature, and the prowess of the hunter. For Costa, these scenes provided an opportunity to display his exceptional skill in rendering textures – the softness of feathers, the sleekness of fur, the cold gleam of metal – and his understanding of animal anatomy.

His compositions were carefully arranged, often creating a poignant contrast between the stillness of death and the implied vitality of the creatures in life. The term "morte della natura" itself carries a slightly more somber or reflective connotation than the English "still life," hinting at the transience of life and the raw beauty found even in death. This focus allowed Costa to explore themes of mortality and the natural cycle within a framework of exquisite realism.

Artistic Style and Technique

Oreste Costa worked primarily in oils, a medium that allowed for rich coloration and the detailed layering necessary for his realistic approach. His technique was characterized by fine, precise brushwork and a meticulous attention to detail. He was adept at capturing the subtle variations in color and texture, bringing an almost tactile quality to his subjects. Whether depicting the iridescent plumage of a pheasant or the rough weave of a game bag, Costa's rendering was consistently skillful.

His palette, while capable of richness, often leaned towards earthy tones and naturalistic hues appropriate for his subject matter. The play of light and shadow was crucial in his compositions, used to model forms, create depth, and highlight the textures of the objects depicted. While rooted in the academic tradition of his training, Costa's realism was not merely photographic; it was imbued with a sensitivity to the subject that elevated his works beyond simple imitation.

Compared to the more revolutionary approaches of some contemporaries, like the aforementioned Macchiaioli or the burgeoning Impressionist movement in France (with artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir), Costa's style was more aligned with the established traditions of realistic still life painting. However, within this tradition, he demonstrated considerable artistry and a distinctive personal vision. His commitment to verisimilitude was shared by other Italian realists of the period, such as Filippo Palizzi (1818-1899), who was also renowned for his animal paintings, though often depicting living animals in pastoral settings.

Notable Works and Themes

Several works by Oreste Costa exemplify his mastery of the still life genre. Among his known pieces is "Martata nature con zacchettone" (Still Life with Game Bag/Hunting Jacket). The title itself suggests a typical composition for the artist: carefully arranged game, perhaps alongside a hunter's accoutrements. Such a painting would showcase his ability to render diverse textures and create a narrative, however subtle, around the theme of the hunt.

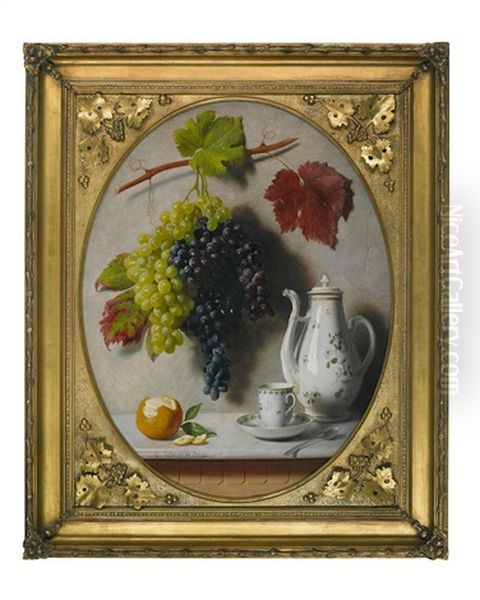

Another documented work is "A still life with grapes and tea pot." This indicates that Costa's repertoire within still life was not exclusively limited to game. Depictions of fruit, tableware, and other domestic objects were also part of the still life tradition, allowing artists to explore different forms, colors, and reflective surfaces. This particular title suggests a more conventional, perhaps more serene, still life composition, contrasting with the "morte della natura" theme.

The painting titled "La morte della natura" (The Death of Nature) directly points to his central thematic concern. Such a work would likely be a quintessential example of his skill in depicting game with both realism and a certain pathos. These paintings often featured birds like partridges, woodcocks, or ducks, and small mammals such as hares or rabbits, sometimes suspended, sometimes laid out on a surface, perhaps with hunting horns, powder flasks, or rifles.

The precision in these works can be compared to the detailed still lifes of earlier masters, yet Costa's paintings possess a distinctly 19th-century sensibility. His focus was less on overt moralizing or complex allegories (common in some earlier still lifes) and more on the faithful and aesthetically pleasing representation of the natural world, albeit in its "stilled" or "deceased" state.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Oreste Costa's talent did not go unnoticed during his lifetime. He actively participated in the art world by exhibiting his works in several major European cities. Records show that his paintings were displayed in prestigious exhibitions in Paris, London, and, of course, Florence. Participation in such exhibitions was crucial for an artist's career, providing visibility, opportunities for sales, and critical reception.

Paris, as the undisputed art capital of the 19th century, hosted the influential Salons, which attracted artists from all over Europe. Exhibiting in Paris was a significant achievement. London, too, had a vibrant art market and important venues like the Royal Academy. Florence, his home base, naturally provided a local platform for showcasing his art. The fact that Costa's works were accepted and shown in these competitive international arenas speaks to the quality and appeal of his paintings.

His works were acquired by collectors, including, as noted in some records, prominent individuals such as Gale Lewis of Pennsylvania. This indicates an international reach for his art, extending beyond Italian borders. Today, Oreste Costa's paintings continue to appear in art auctions, demonstrating an ongoing, albeit specialized, market interest in his work. For instance, a small oil painting (20x13 cm) was recorded as sold for 120 Euros, indicating that his works are accessible to a range of collectors.

The Artistic Milieu of Late 19th-Century Italy

To fully appreciate Oreste Costa's contribution, it's important to consider the broader artistic context of late 19th-century Italy. Following the Unification of Italy (the Risorgimento), which culminated in the 1860s and 1870s, there was a search for a national artistic identity. This period saw a diverse range of artistic expressions.

Academic art, with its emphasis on historical, mythological, and religious subjects, continued to be influential, upheld by institutions like the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence where Costa studied. Artists like Domenico Morelli (1823–1901) in Naples, though innovative in his own right with his dramatic historical and religious scenes, still operated within a broadly academic framework, albeit infused with Romantic and Realist tendencies. Francesco Hayez (1791–1882), a leading figure of Italian Romanticism, had left a lasting legacy, particularly with his historical paintings and portraits.

Alongside academicism, Realism gained significant traction. The Macchiaioli, as mentioned, were pioneers of a particular brand of Italian Realism. Later in the century, Verismo, a literary movement with parallels in the visual arts, emphasized the depiction of everyday life and contemporary social realities, often with a focus on the less privileged classes. While Costa's still lifes were not overtly social commentary, their meticulous realism aligned with the broader Verist sensibility for truthfulness in representation.

Other notable Italian painters of the era included Giovanni Boldini (1842–1931) and Giuseppe De Nittis (1846–1884), both of whom achieved considerable international fame, particularly in Paris. Boldini was celebrated for his flamboyant portraits of high society, characterized by dynamic brushwork, while De Nittis captured modern urban life and landscapes with an Impressionistic touch. Their styles differed greatly from Costa's, yet they represent the diversity of Italian art during this period. Antonio Mancini (1852-1930), known for his thickly impastoed portraits, also emerged as a distinctive voice.

In the realm of sculpture, artists like Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929) were gaining acclaim for their realistic and expressive figures, often depicting common people. This broader turn towards realism in various forms provided a fertile ground for an artist like Costa, whose work, though focused on a specific genre, shared the contemporary concern for accurate observation and skilled representation.

Oreste Costa's Legacy and Historical Assessment

Oreste Costa passed away in 1901. In the grand narrative of art history, he might not occupy the same prominent position as the leading innovators of his time or those who spearheaded major artistic movements. However, his contribution is significant within his chosen field and for understanding the diversity of artistic practice in late 19th-century Italy.

His dedication to "natura morta," particularly scenes with game, places him in a long lineage of still life painters. He brought to this tradition a high level of technical proficiency, likely honed under the demanding tutelage of Antonio Ciseri, and a keen observational skill. His works are valuable not only for their aesthetic qualities but also as documents of a particular taste and cultural interest in the subject of the hunt and the natural world.

While detailed information about his personal life or extensive critical analyses of his oeuvre might be less abundant compared to more famous artists, his paintings speak for themselves. They reveal an artist deeply committed to his craft, capable of rendering his subjects with both precision and sensitivity. His participation in international exhibitions underscores the recognition he received during his lifetime.

For art historians and enthusiasts of 19th-century Italian art, Oreste Costa's work offers a focused lens on a specific genre, executed with a skill that reflects the high standards of academic training prevalent at the time. His paintings serve as a reminder that the art world is composed not only of revolutionary figures but also of dedicated artists who excel within established traditions, refining and reinterpreting them for their own era. Artists like Gaetano Chierici (1838-1920), with his detailed genre scenes of domestic life, or Francesco Paolo Michetti (1851-1929), known for his vibrant depictions of Abruzzese folk life and nature, further illustrate the rich tapestry of Italian art in which Costa operated, each contributing to the cultural landscape in their unique way.

Conclusion

Oreste Costa stands as a noteworthy Italian painter of the late 19th century, a master of the still life genre with a particular focus on "morte della natura." Educated in the rich artistic environment of Florence and a student of the esteemed Antonio Ciseri, Costa developed a style characterized by meticulous realism and technical finesse. His depictions of game and other natural subjects were exhibited in major European art centers, earning him recognition among collectors and peers. While the sweeping changes of modernism were beginning to unfold elsewhere, Costa dedicated himself to a tradition that valued careful observation and skilled execution, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be appreciated for its artistry and its faithful representation of the natural world. His paintings offer a quiet yet compelling insight into a specific facet of 19th-century European art.