The Dutch Golden Age, spanning roughly the 17th century, was a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing in the Netherlands. While masters like Rembrandt van Rijn and Johannes Vermeer captured the human condition and serene domesticity, and painters like Jacob van Ruisdael depicted sweeping landscapes, a fascinating niche was being explored by artists drawn to the intricate details of the natural world. Among the most unique and intriguing figures in this realm was Otto Marseus van Schrieck, a Dutch painter celebrated for his specialization in a genre he helped pioneer: the sottobosco, or forest floor still life. Born in Nijmegen around 1619 or 1620 and dying in Amsterdam in 1678, Van Schrieck carved a distinct path, creating dark, humid, and intensely detailed depictions of the creatures and plants inhabiting the shadowy undergrowth. His work stands at a compelling intersection of meticulous observation, artistic invention, and perhaps even early scientific curiosity.

Early Life and Formative Travels

Details about Otto Marseus van Schrieck's early training remain scarce. Unlike many contemporaries whose apprenticeships are well-documented, his path to becoming a painter is less clear. However, growing up in the vibrant artistic environment of the Dutch Republic, he would undoubtedly have been exposed to the burgeoning tradition of still life painting, which ranged from the opulent floral arrangements of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder to the detailed breakfast pieces popularised in Haarlem. What is certain is that, like many Northern European artists of his time, Van Schrieck embarked on a formative journey abroad, the "Grand Tour," which significantly shaped his artistic vision.

His travels took him through France and, most importantly, to Italy, where he spent a considerable period, primarily between the late 1640s or early 1650s and around 1657. He resided in both Rome and Florence, immersing himself in the artistic currents of the Italian peninsula. This Italian sojourn was crucial not only for exposure to Italian art but also for the connections he forged with fellow artists and patrons. It was during this time that his unique specialization likely began to crystallize, moving away from more conventional still life subjects towards the dark, teeming world of the forest floor.

The Bentvueghels and Roman Context

In Rome, Van Schrieck became associated with the "Bentvueghels" (Dutch for "Birds of a Feather"), a society of mostly Dutch and Flemish artists working in the city. This confraternity was known for its bohemian lifestyle, initiation rituals, and the adoption of catchy nicknames, or "bent" names. Van Schrieck received the moniker "de Snuffelaer," meaning "the Snuffler" or "the Inquisitive One." This nickname likely alluded to his habit of meticulously searching low to the ground in woods and fields for the subjects of his paintings – the insects, reptiles, amphibians, and fungi that would become his trademark.

The Bentvueghels provided a network of support and camaraderie for Northern artists far from home. While known for their sometimes raucous behaviour, which occasionally brought them into conflict with Roman authorities, the group fostered artistic exchange. Other members over time included painters like Cornelis van Poelenburgh and Bartholomeus Breenbergh, though they were active slightly earlier than Van Schrieck's main period in Rome. Within this milieu, Van Schrieck developed his distinctive approach, perhaps finding encouragement for his unconventional subject matter among peers who valued originality.

Artistic Circles and Patronage in Italy

Van Schrieck's time in Italy was marked by significant professional relationships. He travelled and worked closely with fellow Dutch still life painter Willem van Aelst. They reportedly shared lodgings in Florence and Rome, and their artistic paths were intertwined during these years. While Van Aelst specialized more in luxurious still lifes featuring flowers, fruit, and hunting trophies, the shared experience in Italy likely fostered mutual influence, particularly in terms of technique and perhaps composition.

Van Schrieck's unique paintings attracted high-profile patrons. He worked for Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, in Florence. According to the Dutch art theorist Arnold Houbraken, writing decades later in his De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters), the Grand Duke was so impressed with Van Schrieck's work that he awarded him a valuable gold chain and medallion. He also enjoyed the patronage of Cardinal Leopoldo de' Medici, another avid collector with interests in both art and natural history. Furthermore, Van Schrieck associated with the circle around Cassiano dal Pozzo, a renowned scholar and patron whose ambitious 'Paper Museum' aimed to document the natural and ancient worlds through drawings. Van Schrieck may have contributed botanical or zoological studies, blurring the lines between artistic representation and scientific illustration. His detailed observations were later noted by the pioneering Dutch entomologist Jan Swammerdam. He also connected with Italian artists like Paolo Porpora, a Neapolitan painter known for his own rich still lifes, sometimes including undergrowth elements.

Pioneering the Sottobosco Genre

Otto Marseus van Schrieck is inextricably linked with the sottobosco (Italian for "undergrowth") genre. While elements of detailed nature studies, including insects and plants, can be found in earlier works, such as the borders of manuscripts or in the detailed foregrounds of paintings by artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder, Van Schrieck made this specific micro-environment the primary subject of his art. He elevated the damp, dark, and often overlooked world beneath the trees to the status of a major artistic theme.

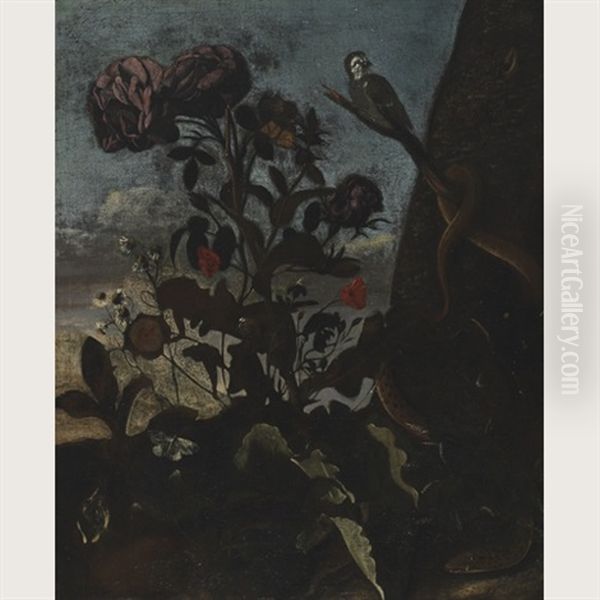

A typical Van Schrieck sottobosco presents a low viewpoint, looking directly into a patch of forest floor. The scene is usually dimly lit, evoking a sense of humidity and mystery. Central elements include various species of fungi, mosses, thistles, and other wild plants, often depicted in a state of growth or decay. Crawling, slithering, or fluttering through this environment are snakes, lizards, frogs, toads, snails, spiders, beetles, butterflies, and moths. These creatures are not merely decorative additions; they are the protagonists of these miniature dramas, often shown interacting – a snake poised to strike a butterfly, a lizard stalking an insect. This focus set his work apart from the brightly lit, often idealized floral bouquets or fruit displays that dominated much of Dutch still life painting.

A Unique Vision: Style and Technique

Van Schrieck's style is characterized by meticulous realism and a palpable sense of atmosphere. He rendered the textures of moss, fungi, reptile skin, and insect wings with extraordinary precision, bordering on hyperrealism. This detailed approach aligns with the Dutch tradition of fijnschilders (fine painters), exemplified by artists like Gerard Dou, who valued intricate detail and a smooth finish. However, Van Schrieck applied this technique to subjects often considered lowly or even repulsive.

His use of chiaroscuro – strong contrasts between light and dark – is fundamental to his style. Subjects are often dramatically illuminated against profoundly dark, almost black, backgrounds, heightening the sense of mystery and focusing the viewer's attention on the details. His palette typically relies on earthy tones: deep browns, greens, greys, and blacks, reflecting the natural colours of the forest floor. These sombre tones are often punctuated by the vibrant hues of a butterfly's wing, the bright cap of a mushroom, or the striking pattern of a snake's skin.

Perhaps the most famous aspect of his technique, also documented by Houbraken, was lepidochromy: the practice of using actual butterfly or moth wings in his paintings. He would apparently press the wings onto a tacky layer of paint or varnish, transferring the delicate scales directly onto the canvas to capture their iridescent colours and powdery texture with unparalleled realism. This innovative, if somewhat eccentric, technique underscores his commitment to capturing the authentic appearance of his subjects, merging the actual object with its painted representation.

The Vivarium Painter: Observation and Accuracy

Van Schrieck's dedication to accuracy extended beyond mere technique. Anecdotes, again relayed by Houbraken and seemingly confirmed by the artist's widow Margarita Gysels after his death, describe him maintaining a vivarium or terrarium at his estate outside Amsterdam. Here, he reportedly kept snakes, lizards, insects, and other creatures he intended to paint. This allowed him to observe their postures, movements, and interactions firsthand, lending an exceptional degree of naturalism to his depictions.

This practice positions Van Schrieck not just as an artist but as a keen observer of nature, almost a proto-naturalist. In an era when scientific inquiry was rapidly advancing, particularly in the Netherlands with figures like Antonie van Leeuwenhoek developing microscopy, Van Schrieck's approach reflected a deep curiosity about the natural world. His paintings, while artistic creations, also served as records of biodiversity and animal behaviour, capturing details that resonated with contemporary naturalists like Swammerdam.

Layers of Meaning: Symbolism in the Undergrowth

While celebrated for their realism, Van Schrieck's paintings are often imbued with symbolic meaning, inviting deeper interpretation. The sottobosco setting itself, with its cycle of growth, decay, and predation, readily lent itself to vanitas themes – meditations on the transience of life, the inevitability of death, and the fleeting nature of beauty. Fungi, symbols of rapid growth and decay, feature prominently. The ephemeral beauty of butterflies and moths, often juxtaposed with predators like snakes or spiders, could symbolize the fragility of the soul or life itself.

The recurring motif of a snake, often depicted threateningly, carries traditional connotations of evil, temptation (as in the Garden of Eden), and death. Its conflict with a butterfly or moth might represent the struggle between good and evil, or spirit and base matter. However, interpretations can be complex. The snake could also symbolize regeneration (due to shedding its skin) or even wisdom in some contexts. The intense focus on predation and the interconnectedness of the creatures within this ecosystem – predator and prey, decay providing nutrients for new growth – has led some modern scholars to see in Van Schrieck's work an early, intuitive grasp of ecological relationships, long before ecology emerged as a formal scientific discipline. His work contrasts sharply with the often purely celebratory or decorative intent of flower painters like Jan van Huysum, engaging instead with the darker, more complex aspects of nature.

Masterworks of the Forest Floor

Several key works exemplify Otto Marseus van Schrieck's unique contribution to art history. His Still Life with Poppy, Insects, and Reptiles (c. 1670), housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is a quintessential example. A large, drooping poppy head, potentially symbolizing sleep or death, anchors the composition. Around it, a typical cast of characters unfolds against a dark background: a snake slithers menacingly, a lizard pauses alertly, various butterflies (possibly created using lepidochromy), a snail, and meticulously rendered fungi and thistles fill the shadowy space. The detail is exquisite, from the texture of the snake's scales to the delicate veins on the poppy petals.

Another work, often titled Forest Floor Still Life with Snake, Lizards, and Butterflies or similar variations, showcases the dynamic interactions he favoured. Such paintings often depict a moment of tension – a snake striking, lizards fighting, or insects caught by predators. These compositions highlight the struggle for survival that characterizes the natural world, rendered with both scientific precision and dramatic flair.

His earlier painting, Forest Floor with Mushrooms, Snake, and Scorpion (1655), now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, dates from his Italian period. It demonstrates that his signature style and subject matter were already well-established during his time abroad. The inclusion of a scorpion adds an extra element of danger and exoticism. Works by Van Schrieck can also be found in other major collections, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, each offering a glimpse into his specialized, miniature world.

Amsterdam, Marriage, and Later Life

Around 1657, or possibly slightly later after travels that may have included England and France, Van Schrieck returned to the Netherlands and settled in Amsterdam, which was then the bustling centre of Dutch commerce and culture. In 1664, he married Margarita Gysels (or Gijzels), who reportedly shared his interest in nature. The couple lived near the Vijzelgracht, and later acquired a country property outside the city called "Waterrijk" (Water Realm) near Ilpendam. This estate likely provided him with ample opportunity to cultivate plants and observe the creatures that populated his paintings, functioning as both a garden and a natural laboratory.

He continued to paint actively in Amsterdam, maintaining his reputation as a specialist in sottobosco scenes. His works were sought after by collectors who appreciated their unique subject matter and technical brilliance. He remained in Amsterdam until his death in June 1678; he was buried in the Nieuwezijds Kapel. His wife survived him by many years, living until 1720 and providing Arnold Houbraken with valuable biographical information about her late husband.

Legacy and Influence

Otto Marseus van Schrieck occupied a unique niche within the diverse landscape of Dutch Golden Age painting, and his influence, though specialized, was significant. He was a key figure in establishing the sottobosco as a distinct subgenre of still life. His most famous follower was Rachel Ruysch, one of the most successful female painters of the era. In her early career, before she became renowned for her elaborate floral compositions, Ruysch painted several forest floor scenes that clearly show the direct influence of Van Schrieck, possibly having trained with him or studied his work closely. Her technical skill in rendering detail owes a debt to the fijnschilder tradition that Van Schrieck also embodied.

Other artists who worked in a similar vein, focusing on forest floor subjects, include Matthias Withoos, who also painted townscapes, and possibly Elias van den Broeck and Abraham Mignon, although Mignon is better known for his fruit and flower pieces. Van Schrieck's work can also be seen in dialogue with other artists interested in the natural world, such as the animal painter Melchior d'Hondecoeter, known for his depictions of birds, or even Maria Sibylla Merian, the celebrated artist-naturalist whose detailed studies of insects and plants, often showing life cycles, share Van Schrieck's commitment to close observation, though her style and scientific intent were distinct. His focus on the dark and wild aspects of nature provides a fascinating counterpoint to the more orderly or idealized visions presented by contemporaries like the landscape painter Nicolaes Berchem or the flower specialist Jan Davidsz. de Heem.

An Enduring Enigma

Otto Marseus van Schrieck remains a somewhat enigmatic figure in the grand narrative of Dutch art. He was not a painter of grand historical scenes, insightful portraits, or serene domestic interiors. Instead, he dedicated his considerable skill to depicting a world often overlooked, hidden in the shadows of the forest floor. As "de Snuffelaer," he explored the intricate beauty and inherent dangers of this micro-ecosystem, blending meticulous observation worthy of a naturalist with the dramatic composition and symbolic depth of a Baroque painter.

His innovative use of techniques like lepidochromy and his practice of keeping live specimens highlight an unusual dedication to realism and direct experience. The sottobosco paintings he pioneered offer a unique window into the 17th-century fascination with the natural world, standing at the crossroads of art, science, and symbolism. While perhaps less famous than some of his contemporaries, Otto Marseus van Schrieck's contribution was distinct and enduring, enriching the Dutch Golden Age with his dark, detailed, and captivating visions of life in the undergrowth. His work continues to fascinate viewers with its blend of beauty, decay, and the quiet drama of the natural world.