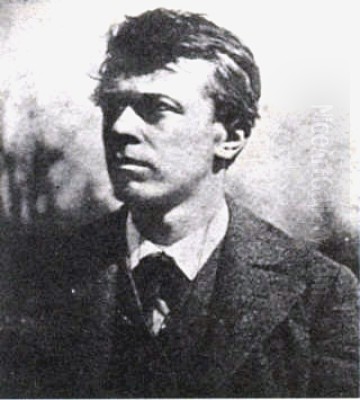

Otto Reiniger (1863–1909) stands as a significant figure in the realm of German art, particularly associated with the Swabian Impressionist movement. His life and work unfolded during a period of profound artistic transformation in Europe, witnessing the zenith of Impressionism and the dawn of various avant-garde movements. While his primary contributions were in painting, the name Reiniger also resonates powerfully in the pioneering field of animation, albeit through a different, though equally innovative, artist. This exploration delves into the life, style, and context of Otto Reiniger the painter, while also acknowledging the distinct yet remarkable legacy of Lotte Reiniger in animation, to provide a comprehensive view of the artistic contributions associated with this notable German surname.

The Life and Times of Otto Reiniger

Born in Stuttgart in 1863, Otto Reiniger emerged as an artist in a Germany that was increasingly engaging with international artistic currents. His formative years and artistic training were rooted in the academic traditions of the time, yet he became a key proponent of Impressionism in the Swabian region of southwestern Germany. This area, known for its distinct cultural identity and picturesque landscapes, provided fertile ground for artists seeking to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere in their work.

Reiniger's career coincided with a vibrant period in German art. While French Impressionism, championed by artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, had already made its mark, German artists were developing their own interpretations. Figures like Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt became leading exponents of German Impressionism, often infusing it with a more robust, sometimes more psychologically charged, character than their French counterparts. Otto Reiniger found his niche within this broader movement, focusing on the specific landscapes and light conditions of his native Swabia.

Swabian Impressionism and Reiniger's Artistic Style

Swabian Impressionism, while sharing the core tenets of its French precursor – an emphasis on plein air painting, capturing transient moments, and the subjective experience of light and color – often possessed a more intimate and regionally focused character. Otto Reiniger was a central figure in this regional school, alongside contemporaries such as Hermann Pleuer, known for his depictions of railway stations and industrial scenes, and Christian Landenberger, who also explored light effects on water and in landscapes.

Reiniger's paintings are characterized by their sensitive rendering of light and atmosphere, often depicting the gentle hills, river valleys, and forests of Swabia. His brushwork, typical of Impressionist technique, would have been visible and dynamic, aiming to convey the immediacy of sensory experience rather than a meticulously detailed representation. While specific titles of his most famous paintings are not always widely circulated in general art historical surveys focused on broader movements, his oeuvre contributed significantly to the regional identity of Swabian art. His works are held in various German museums and private collections, attesting to his importance within this specific context. He was a student at the Stuttgart Academy, likely studying under or alongside figures influential in the region, such as Albert Kappis, whose own students included Erwin Starker, Hermann Drück, and Felix Hollenberg, further embedding Reiniger within this Swabian artistic network. His association with Carlos Grethe, another Stuttgart Impressionist, also highlights his active participation in this local art scene.

The Broader Artistic Milieu: Expressionism and Beyond

While Otto Reiniger was firmly rooted in Impressionism, his later years overlapped with the emergence of German Expressionism, a movement that would radically reshape the artistic landscape. Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde, founders of Die Brücke (The Bridge) group, as well as figures like Egon Schiele and Otto Dix (though Dix's most impactful work came slightly later), were pushing art in new directions, emphasizing intense emotion, subjective vision, and often distorted forms and bold, non-naturalistic colors.

Although Reiniger's style did not align with Expressionism, the burgeoning of such movements created a dynamic and often contentious artistic environment. The cultural scene was rich and varied, encompassing not only painting but also innovations in other fields. For instance, stage designers like Carl August Reinhardt and Louis Reinhardt were contributing to the theatrical arts, reflecting a period of widespread creative ferment. The historical painter Christian Speyer (1855–1929) also represents another facet of the artistic production of that era, often looking to historical themes, which stood in contrast to the Impressionists' focus on contemporary life and landscape.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Otto Reiniger's work was recognized during his lifetime and posthumously through various exhibitions. Notably, a significant collection of his paintings, numbering around fifty-five, was exhibited at Villa Berg in Stuttgart, a testament to his standing in the region. His works also found their way into Stuttgart's burgeoning gallery scene, which laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the Stuttgart State Gallery (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart), one of Germany's prominent art museums. The inclusion of his name and works in art reference libraries and historical surveys of Swabian art further solidifies his place in German art history.

A Different Reiniger: The Magic of Silhouette Animation

It is impossible to discuss the name "Reiniger" in the context of early 20th-century German art without acknowledging the groundbreaking work of Lotte Reiniger (1899–1981). Though a different individual from a later generation, and working in a distinct medium, her innovations in silhouette animation represent a monumental achievement in the history of film and animation. It is important to clarify that Otto Reiniger the painter and Lotte Reiniger the animator are distinct individuals, but the shared surname sometimes leads to conflation of their artistic domains.

Lotte Reiniger was a true pioneer, best known for creating The Adventures of Prince Achmed (Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed), released in 1926. This is widely considered the oldest surviving feature-length animated film, predating Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs by over a decade. Her technique involved meticulously cutting out articulated paper silhouettes and animating them frame by frame against illuminated backgrounds. This method, inspired by traditional Chinese shadow puppetry and European paper-cutting traditions (Scherenschnitte), resulted in films of exquisite beauty and intricate detail.

Lotte Reiniger's artistic style in her animations drew from various influences. The visual language of German Expressionism, with its dramatic use of light and shadow, is evident, as are elements that could be seen as aligning with the decorative qualities of Art Nouveau or Jugendstil. Her narratives often drew from fairy tales, myths, and classic literature, such as Cinderella (Aschenputtel, 1922), Sleeping Beauty (Dornröschen, 1922/1954), The Rose and the Ring (based on Thackeray's story), and adaptations for works like Dr. Dolittle. Her collection Musik & Zaubereien (Music & Magic) further showcases her mastery.

She was an innovator not only in artistry but also in technology, developing an early version of the multiplane camera, which she called the "trick table." This device allowed for the creation of a sense of depth by layering different silhouette elements and backgrounds, which could be moved independently. This invention was a significant precursor to the more complex multiplane cameras later famously used by Disney.

Lotte Reiniger was part of a vibrant avant-garde circle in Berlin. She collaborated with notable figures of the Weimar era, including the playwright Bertolt Brecht, for whom she created animated sequences. She also worked with experimental filmmakers like Walter Ruttmann and was associated with the broader intellectual and artistic climate that included figures like director Fritz Lang (director of Metropolis and M) and G.W. Pabst. Her work, while unique, can be seen in dialogue with other experimental animation and film practices of the time, and even with movements like Dada, through artists such as Hannah Höch, who also utilized collage and cut-paper techniques, albeit for different artistic ends, often with a socio-political critique. The ethos of the Bauhaus movement, with its emphasis on the synthesis of art, craft, and technology, also resonates with Lotte Reiniger's meticulous and innovative approach to her craft, even if she was not formally part of the school.

Otto Reiniger's Enduring Legacy in Painting

Returning to Otto Reiniger the painter, his legacy lies primarily in his contribution to Swabian Impressionism. He successfully translated the principles of French Impressionism into a regional German context, capturing the unique character of his homeland with sensitivity and skill. His work, alongside that of his contemporaries like Pleuer and Landenberger, helped to establish a distinct school of landscape painting that celebrated the local environment.

While perhaps not as internationally renowned as the leading figures of French Impressionism or the German Expressionists who followed, Otto Reiniger's role within his specific artistic milieu was significant. He represents an important chapter in the story of German Impressionism, demonstrating how this revolutionary approach to painting was adapted and reinterpreted across different regions and by individual artistic temperaments. His dedication to capturing the nuances of light and landscape in Swabia ensured his place as a respected artist of his time and a key figure in the art history of southwestern Germany.

The period in which Otto Reiniger worked was one of immense artistic dynamism. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a rapid succession of styles and movements, from the lingering influence of academic art to the revolutionary breakthroughs of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism. Reiniger's commitment to Impressionism, even as newer, more radical styles emerged, speaks to the enduring appeal of its aesthetic principles and its capacity to convey the beauty and transience of the natural world. His art provides a valuable window into a specific regional manifestation of a global art movement, enriching our understanding of the diverse tapestry of European art at the turn of the century.

In conclusion, Otto Reiniger (1863-1909) was a dedicated and skilled German painter who made a lasting contribution to Swabian Impressionism. His work reflects a deep engagement with the landscapes of his native region and a mastery of Impressionist techniques for capturing light and atmosphere. While the name Reiniger also shines brightly in the history of animation through the pioneering efforts of Lotte Reiniger, Otto Reiniger the painter holds his own distinct and important place in the annals of German art, remembered for his evocative depictions of Swabia and his role in a significant regional art movement. His contemporaries, from fellow Impressionists like Max Liebermann and Hermann Pleuer to the emerging Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde, and even figures from other artistic disciplines, all contributed to the rich cultural fabric of Germany during this transformative era.