Samu Bortsok stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of early 20th-century Hungarian art. A dedicated member of the influential Nagybánya artists' colony, Bortsok's work is characterized by its lyrical engagement with landscape, its sensitive rendering of light and atmosphere, and its adherence to the principles of plein air painting. While his contemporaries across Europe were exploring radical new forms of expression, Bortsok and his Nagybánya colleagues forged a distinctly Hungarian path, deeply rooted in the observation of nature yet infused with modern sensibilities.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Tárcsó, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Tarcău, Romania), in 1891, Samu Bortsok's early life unfolded during a period of intense cultural and nationalistic fervor in Hungary. This era saw a burgeoning desire among artists and intellectuals to define and celebrate a unique Hungarian cultural identity, distinct from the dominant Viennese influence. It was in this environment that Bortsok's artistic inclinations began to take shape, leading him towards the Nagybánya colony, a crucible of modern Hungarian art.

The precise details of his earliest artistic training are somewhat sparse in widely available records, a common challenge with artists who were not at the absolute epicenter of Parisian or Viennese art circles. However, his eventual association with Nagybánya indicates a foundational education that would have equipped him with the necessary skills in drawing and painting, likely through private tutors or regional art schools before he gravitated towards the colony's more progressive and nature-focused ethos.

The Nagybánya Artists' Colony: A Crucible of Hungarian Modernism

The Nagybánya artists' colony, founded in 1896 by Simon Hollósy, Károly Ferenczy, István Réti, János Thorma, and Béla Iványi-Grünwald, was a pivotal institution in the development of modern Hungarian art. Located in what is now Baia Mare, Romania, it became a haven for artists seeking to escape the rigid academicism of established art institutions. The colony championed plein air (outdoor) painting, direct observation of nature, and a focus on capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere. It was here that Bortsok found his artistic home and developed his signature style.

Bortsok's involvement with Nagybánya placed him in direct contact with its leading figures and their philosophies. Károly Ferenczy, often considered the most significant painter of the colony, was particularly influential with his synthesis of naturalism and decorative stylization, often imbued with a gentle, melancholic mood. Simon Hollósy, the initial leader, emphasized rigorous study from nature. These influences, combined with the communal spirit of the colony, profoundly shaped Bortsok's artistic trajectory. He absorbed the colony's commitment to depicting the Hungarian landscape with honesty and sensitivity.

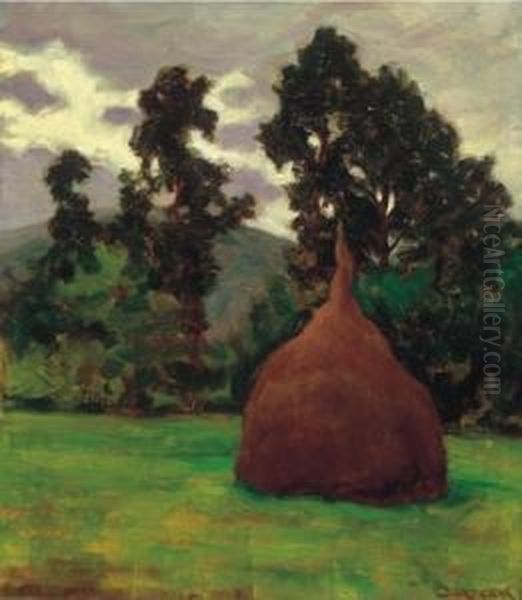

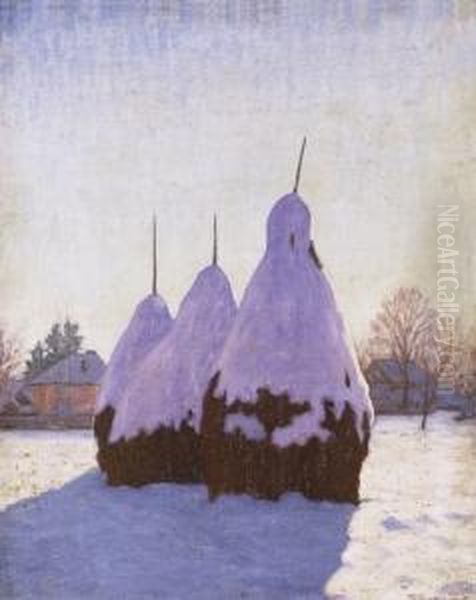

His works from this period, such as "Nagybánya Landscape" or "Winter in Nagybánya" (representative titles, as specific famous works can be hard to pinpoint without museum access), exemplify the Nagybánya style. They often feature broad, confident brushstrokes, a keen attention to the play of light across surfaces, and a harmonious color palette that captures the specific character of the region's landscapes through different seasons. Bortsok was particularly adept at conveying the mood of a scene, whether the crisp clarity of a winter day or the lush vibrancy of summer.

Artistic Style: Light, Color, and Atmosphere

Samu Bortsok's artistic style is firmly rooted in Post-Impressionism, with a particular emphasis on the principles learned and practiced at Nagybánya. He was not an artist of radical experimentation in form in the way some of his European contemporaries were, but rather one who sought to refine and personalize the depiction of observed reality. His primary concern was the landscape, and his paintings are testaments to his deep connection with the natural world.

Light was a central element in Bortsok's work. He meticulously studied how light interacted with the environment, how it defined forms, created shadows, and infused scenes with particular emotional qualities. His canvases often glow with an inner luminosity, achieved through careful color choices and an understanding of tonal values. Unlike the Impressionists who sought to capture a fleeting moment, Bortsok and his Nagybánya peers often aimed for a more structured and enduring representation, though still imbued with freshness and spontaneity.

His color palette was typically rich and nuanced, reflecting the natural hues of the Hungarian countryside. He avoided overly strident or artificial colors, preferring a harmony that was true to life yet artistically expressive. Brushwork in Bortsok's paintings is often visible and energetic, contributing to the vitality of his scenes without dissolving form entirely. There is a sense of solidity and structure in his compositions, even as he masterfully renders the ephemeral qualities of weather and light.

Navigating a World of Artistic Revolutions

While Samu Bortsok was diligently painting the landscapes around Nagybánya, the broader European art world was in a state of dynamic upheaval. In Paris, artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were spearheading the Cubist revolution. Picasso's "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon," painted in 1907, had shattered traditional notions of perspective and representation, breaking down objects into geometric forms and depicting them from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. This analytical approach, with its emphasis on the two-dimensionality of the canvas and the deconstruction of form, was a world away from Bortsok's commitment to plein air observation and atmospheric naturalism.

The early 20th century also witnessed the rise of Fauvism, with artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain using bold, non-naturalistic colors for expressive effect. German Expressionism, with groups like Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, explored intense emotional states and subjective realities, often through distorted forms and vibrant hues. Figures like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Wassily Kandinsky were pushing art in directions that prioritized inner vision over outward appearance. Even later, the seeds of Dadaism, a reaction to the perceived irrationality of World War I, were being sown, challenging the very definition of art.

Bortsok's art, therefore, existed in a context of immense artistic diversity. His choice to remain focused on landscape and the principles of Nagybánya was not a sign of ignorance of these developments, but rather a conscious decision to pursue a path that resonated with his own artistic temperament and the cultural aspirations of his immediate artistic community. The Nagybánya school itself was a modern movement, a Hungarian response to international trends like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, adapted to local conditions and sensibilities.

Themes and Subjects: The Hungarian Landscape Personified

The predominant theme in Samu Bortsok's oeuvre is the landscape of the Nagybánya region and other parts of Hungary he may have visited. He painted rolling hills, tranquil rivers, dense forests, and quiet village scenes. His works often capture the changing seasons, from the snow-covered landscapes of winter, with their subtle plays of light and shadow on white, to the vibrant greens and blues of spring and summer, and the rich, earthy tones of autumn.

Unlike some landscape traditions that might use nature as a backdrop for historical or mythological narratives, Bortsok's landscapes are typically devoid of overt storytelling. The subject is the land itself, its character, its atmosphere, and the way light transforms it. There is a sense of intimacy and quiet contemplation in his work, inviting the viewer to share in his appreciation for the beauty of the natural world. If figures appear, they are often small and integrated into the landscape, part of the natural rhythm of rural life rather than the central focus.

This dedication to the local landscape was a hallmark of the Nagybánya artists. It was a way of asserting a Hungarian artistic voice, grounding their modernism in the specific soil and light of their homeland. Bortsok's contribution to this collective endeavor was significant, adding his personal vision to the broader tapestry of Nagybánya art.

Comparisons with Other Artistic Approaches

To further understand Bortsok's place, it's useful to consider his work in relation to other artists and movements, even those quite different in style or era. For instance, the intense, often tormented, figurative work of a later artist like Francis Bacon, with its raw emotional power and exploration of the human condition, stands in stark contrast to Bortsok's serene and observational landscapes. Bacon's art, emerging in the post-World War II era, grappled with anxieties and existential themes far removed from the pre-war optimism and nature focus of Nagybánya.

The visionary and mystical art of William Blake, an English Romantic poet and painter from an earlier century, also offers a point of contrast. Blake's work was deeply symbolic, drawing on biblical and mythological sources, and characterized by a highly personal and imaginative iconography. While both Blake and Bortsok might be said to have a profound connection to their environment (Blake to England, Bortsok to Hungary), their modes of expression and artistic aims were vastly different. Blake sought to reveal inner spiritual truths, while Bortsok sought to capture the visual poetry of the external world.

The Realism of Gustave Courbet in 19th-century France provides another interesting comparison. Courbet famously declared he would only paint what he could see, rejecting academic idealism and Romantic melodrama. His commitment to depicting ordinary people and everyday scenes, as in "The Stone Breakers" or "A Burial at Ornans," was revolutionary in its time. Bortsok shared this commitment to direct observation, but his focus was less on social commentary and more on the aesthetic and atmospheric qualities of the landscape. The Nagybánya artists, in a sense, continued the Realist impulse but filtered it through the lens of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist concerns with light and color.

Even within the broader Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements, there were diverse approaches. Edgar Degas, for example, though a key participant in the Impressionist exhibitions, maintained a strong emphasis on drawing and composition, and his subjects often involved urban life, dancers, and racecourses. While Degas captured movement and modern life, Bortsok focused on the timeless qualities of the rural landscape. Both artists, however, were keen observers of their respective worlds, translating their observations into compelling visual forms. Degas's innovative compositions and use of unconventional viewpoints also set him apart, whereas Bortsok's compositions tended to be more traditional, though always effective in conveying the chosen scene.

The Dynamics of the Art World: Cooperation and Competition

The art world, throughout history, has been characterized by complex relationships between artists, involving both cooperation and competition. While detailed accounts of Samu Bortsok's personal interactions and rivalries are not widely documented, the very nature of an artists' colony like Nagybánya implies a degree of shared purpose and mutual influence. Artists living and working in close proximity would inevitably learn from one another, share techniques, and engage in critical discussions about their work. This collaborative environment was crucial to the development of the Nagybánya school's distinct identity.

However, even in collaborative settings, a spirit of friendly competition can exist, pushing artists to refine their skills and develop unique voices. The history of art is replete with examples of more intense rivalries, such as the famed competition between Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo in Renaissance Florence, particularly their aborted commissions for frescoes in the Palazzo Vecchio. The intense, sometimes acrimonious, relationship between Caravaggio and some of his contemporaries, like Giovanni Baglione, even led to legal battles. These historical examples illustrate that artistic ambition and the pursuit of patronage and recognition can often lead to friction.

For Bortsok and his Nagybánya colleagues, the primary "competition" might have been with the established academic art institutions and the challenge of gaining acceptance for their more modern approach. Within the colony, while individual artists developed their own styles, the overarching goal was a collective one: to create a vibrant, modern Hungarian art.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and the Artist's Life

Specific colorful anecdotes or major public controversies directly involving Samu Bortsok are not prominent in general art historical accounts. This is often the case for artists who are deeply committed to their craft but do not actively seek the limelight or become embroiled in highly public disputes. His "story" is primarily told through his paintings and his association with Nagybánya.

The art world, however, is no stranger to controversy, which can arise from artistic innovation, personal behavior, or even misinterpretations. The "A1" controversies mentioned in the provided context, such as a public figure's slip of the tongue regarding "AI," disputes in motorsport classifications, debates about A1 versus A2 milk, or issues with animation studios and 3D printer models, are modern examples from diverse fields, far removed from Bortsok's historical and artistic milieu. They serve to illustrate that public discourse and disagreement are common across many areas of human endeavor.

For an artist like Bortsok, any "controversy" would likely have been artistic in nature – perhaps debates within Nagybánya about the direction of their art, or the initial resistance their modern style faced from more conservative elements of the Hungarian art establishment. The very act of breaking from academic tradition, as the Nagybánya artists did, was in itself a challenge to the status quo and could be seen as a form of "artistic controversy" in its time.

Social Engagement and Historical Context

Every artist operates within a specific historical and social context, and their work, consciously or unconsciously, reflects that environment. Samu Bortsok lived and painted during a tumultuous period in Hungarian and European history. His formative years and early career coincided with the final decades of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918), and the subsequent redrawing of European borders, which had a profound impact on Hungary, including the ceding of Transylvania (where Nagybánya was located) to Romania.

While Bortsok's landscapes do not typically depict overt political events or social commentary in the manner of, say, Käthe Kollwitz's powerful anti-war prints or George Grosz's satirical critiques of Weimar society, his dedication to the Hungarian landscape can be interpreted as a form of cultural affirmation. In a period of national uncertainty and transformation, the act of painting one's homeland, of celebrating its beauty and character, can take on deeper significance. The Nagybánya artists' focus on local scenery contributed to the construction of a modern Hungarian cultural identity.

The early 20th century was also a time of significant social change and the rise of various social movements across Europe. While Bortsok's direct involvement in specific social or political activism is not highlighted, the ethos of the Nagybánya colony itself – its break from academic norms, its communal structure, and its focus on a national artistic expression – can be seen as a form of cultural movement. Artists like the Chinese contemporary artist Dai Guangyu, mentioned in the provided context, engage much more directly with social and environmental issues through performance and installation art, reflecting a different era and a different mode of artistic engagement. Dai Guangyu's "Water's Keepers" projects, for example, are overtly activist, a contrast to Bortsok's more contemplative landscape art.

Later Years and Legacy

Samu Bortsok's career continued into the 1920s, but his life was tragically cut short. He passed away in 1931 at the relatively young age of 40. Despite his premature death, he left behind a body of work that remains a testament to his talent and his dedication to the ideals of the Nagybánya school.

His legacy is intertwined with that of Nagybánya itself. The colony played a crucial role in modernizing Hungarian art, and Bortsok was a committed participant in this endeavor. His paintings are preserved in Hungarian museums, including the Hungarian National Gallery, and appear in private collections. They are valued for their lyrical beauty, their skillful rendering of light and atmosphere, and their contribution to the rich tradition of Hungarian landscape painting.

While perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his contemporaries who gravitated to Paris or Berlin, Samu Bortsok holds an important place within Hungarian art history. He represents a generation of artists who sought to create a modern art that was both internationally aware and deeply rooted in their national identity. His sensitive and evocative landscapes continue to resonate with viewers, offering a window into the natural beauty of a specific region as seen through the eyes of a gifted and dedicated artist. His work reminds us that significant artistic contributions often occur beyond the major art capitals, in communities where artists gather to explore shared visions and create art that speaks to their own time and place.