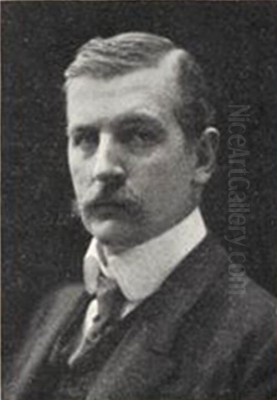

Otto Vautier (1863-1919) stands as an intriguing figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. Born in Düsseldorf, Germany, a vibrant center of artistic activity, he later established himself in Geneva, Switzerland, becoming a Swiss artist whose work reflects both his German academic roots and the evolving artistic currents of his time. While perhaps not achieving the widespread international fame of some of his contemporaries, Vautier carved out a significant career, producing a diverse body of work that spanned oil painting, watercolor, drawing, and printmaking, often focusing on genre scenes, portraiture, and the human condition.

Early Life and Artistic Milieu: The Düsseldorf Legacy

Otto Vautier was born into an artistic family. His father, Benjamin Vautier (the Elder, 1829-1898), was a highly respected Swiss genre painter associated with the Düsseldorf School of painting. This school, centered around the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, was one of the most influential art academies in Europe during the 19th century, renowned for its detailed, narrative-driven genre scenes and landscapes. Artists like Andreas Achenbach and Oswald Achenbach were famed for their dramatic landscapes, while figures such as Ludwig Knaus (a contemporary and sometimes compared with Benjamin Vautier) and Franz von Defregger excelled in depicting peasant life and historical genre scenes with meticulous realism and often a touch of sentimentality.

Growing up in this environment, Otto Vautier would have been immersed in the principles of academic realism from a young age. The Düsseldorf School emphasized strong draftsmanship, careful observation, and a narrative approach to subject matter. While specific details of Otto Vautier's formal art education are not extensively documented in readily available sources, it is highly probable that he received initial training from his father and was deeply influenced by the prevailing artistic ethos of Düsseldorf. This grounding in realistic depiction and storytelling would remain a characteristic feature of much of his work, even as he explored other stylistic avenues.

The artistic climate of Düsseldorf in the latter half of the 19th century was rich and varied. Beyond the core figures of the academy, the city attracted artists from across Europe. The emphasis on genre painting, particularly scenes of rural and peasant life, was a dominant trend, reflecting a broader European interest in documenting the lives of ordinary people, a theme also explored by French artists like Jean-François Millet and Gustave Courbet, albeit often with different social or political undertones.

Artistic Development and Thematic Concerns

Otto Vautier's artistic output demonstrates a versatility in both subject matter and medium. He is known for his depictions of rural life, echoing the traditions of the Düsseldorf School. These works often portray peasants, particularly from regions like the Black Forest, capturing their daily activities, traditional attire, and the landscapes they inhabited. His painting Old Woman and Boy Resting, now in the collection of the Walters Art Museum, is a fine example of this aspect of his work. Acquired by William T. Walters and later bequeathed to the museum, its presence in an American collection speaks to the international appeal of such genre scenes during that period.

Beyond rural themes, Vautier also showed a keen interest in portraiture and the depiction of the female figure. Works like Femme au miroir (Woman at the Mirror) and Nu feminin à pied (Female Nude Standing) highlight his skill in rendering human anatomy and exploring more intimate or allegorical subjects. The use of pastels, as seen in Les Bas bleus (The Blue Stockings), held in the Musée Jenisch Vevey, allowed for a softer, more atmospheric quality, suggesting an engagement with the nuanced textures and light effects popular at the turn of the century.

His drawing Die Freuden der Zukunft (The Joys of the Future), created in 1909 using charcoal and colored pencil, indicates an engagement with Symbolist or allegorical themes. The title itself suggests a departure from straightforward realism towards a more conceptual or imaginative realm. This period saw the rise of Symbolism across Europe, with artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and the Swiss-German Arnold Böcklin exploring themes of dreams, mythology, and the inner world. While Vautier may not be primarily categorized as a Symbolist, works like this suggest his awareness of and participation in these broader artistic currents.

Relocation to Geneva and Swiss Artistic Identity

A significant chapter in Otto Vautier's life and career began with his move to Geneva, Switzerland. He became active in the Genevan art scene from around 1906 and was reportedly considered a "father" figure within certain art groups, indicating a respected position and perhaps a role in mentoring or organizing artistic activities. Geneva, at the turn of the century, was a cosmopolitan city with its own burgeoning art scene. Swiss art was undergoing a period of transformation, with artists seeking to define a modern national identity while engaging with international trends.

Ferdinand Hodler, arguably Switzerland's most famous artist of the era, was a dominant force, developing his distinctive style known as Parallelism, which blended Symbolism with a monumental and rhythmic approach to composition. Other notable Swiss artists of the period included Félix Vallotton, who, though largely active in Paris and associated with the Nabis, maintained his Swiss roots, and Cuno Amiet and Giovanni Giacometti (father of Alberto Giacometti), who were pioneers of modern Swiss painting, experimenting with Post-Impressionism and Fauvism.

Within this Swiss context, Vautier continued to produce and exhibit his work. His German training provided a solid foundation, but his life in Geneva would have exposed him to new influences and artistic dialogues. His diverse output, ranging from oil paintings to works on paper, found an audience, and his pieces were included in exhibitions. The fact that he is often referred to as a Swiss artist underscores the importance of his Genevan period in shaping his artistic identity and legacy.

Representative Works and Stylistic Range

Several works stand out in Otto Vautier's oeuvre, showcasing his stylistic range and thematic interests:

Old Woman and Boy Resting: This oil painting exemplifies his connection to the Düsseldorf genre tradition. It likely features a scene observed from rural life, rendered with attention to character, costume, and setting. The emotional tone, often a hallmark of genre painting, would focus on the dignity or quiet endurance of its subjects.

Die Freuden der Zukunft (1909): This charcoal and colored pencil drawing, held in a private Swiss collection, is notable for its allegorical title. It suggests a departure from pure realism towards a more symbolic or imaginative mode of expression, perhaps reflecting anxieties or hopes about the future, a common theme in art at the cusp of the modern era. The choice of drawing media also highlights his skill as a draftsman.

Les Bas bleus: A pastel work, this piece likely focuses on a female figure, possibly in an interior setting. The title, "The Blue Stockings," historically referred to educated, intellectual women, often with a slightly pejorative connotation of being overly serious or unfeminine. Vautier's interpretation could range from a straightforward portrait to a more nuanced commentary on contemporary womanhood. Its presence in the Musée Jenisch Vevey indicates its recognition within Swiss public collections.

Femme au miroir: While details of this specific work are tied to auction records, the theme of a woman at her mirror is a classic one in art history, explored by artists from Titian to Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot. It allows for explorations of vanity, introspection, beauty, and the passage of time. Vautier's treatment would likely combine his skilled figural representation with a particular mood or narrative.

Nu feminin à pied: An oil painting depicting a standing female nude, this work places Vautier within the academic tradition of life drawing and the artistic exploration of the human form. The nude was a central subject in Western art, allowing artists to demonstrate their mastery of anatomy and to explore ideals of beauty or more expressive interpretations of the body.

His works were disseminated not only as original paintings and drawings but also through prints and photographs, which helped to popularize his images, particularly those depicting peasant life, a genre that had wide appeal.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

To fully appreciate Otto Vautier's position, it's essential to consider him within the broader context of his contemporaries. In Germany, the Düsseldorf School remained influential, but new movements were emerging. Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt were key figures in German Impressionism and later, early Expressionism. The Berlin Secession, founded in 1898, provided a platform for artists breaking away from academic conservatism.

In Switzerland, alongside Hodler, Vallotton, Amiet, and Giacometti, artists like Albert Anker were beloved for their idyllic depictions of Swiss rural life, somewhat akin to the genre scenes Vautier also produced, though Anker's style was perhaps more rooted in an earlier, Biedermeier-influenced realism. The artistic climate was one of transition, with artists grappling with the legacy of 19th-century realism and the rise of modernism.

Internationally, the period Vautier worked in was incredibly dynamic. Post-Impressionism had paved the way for Fauvism (Henri Matisse, André Derain) and Cubism (Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque) in France. Symbolism had a widespread impact, and Art Nouveau influenced decorative arts and painting. While Vautier's work seems more closely aligned with established traditions, particularly genre painting and a form of tempered realism, the existence of works like Die Freuden der Zukunft suggests he was not immune to the symbolic and expressive tendencies of his time.

His relationship with artists like Ludwig Knaus and Franz von Defregger is one of shared thematic interest in peasant genre scenes, stemming from the Düsseldorf tradition. Knaus, like Vautier's father, was a master of this genre, known for his lively and often humorous depictions. Defregger, an Austrian, also specialized in scenes from Tyrolean peasant life and historical events, rendered with a robust realism.

Art Historical Reception and Legacy

Otto Vautier's reception in art history appears to be somewhat mixed, or at least, he is not consistently placed among the foremost innovators of his era. Some contemporary or later critiques have described his style as "mediocre" or "dogmatic," perhaps pointing to a perceived adherence to academic conventions that were being challenged by more avant-garde movements. However, these same critiques often acknowledge a "human sympathy" in his work, recognizing his ability to connect with his subjects and convey a sense of shared humanity. This quality made him a competent "type painter," an artist specializing in characteristic scenes of everyday life.

His works have appeared in auctions, with pieces like Femme au miroir commanding respectable estimates, indicating a continued market interest. The presence of his art in museum collections, such as the Walters Art Museum and the Musée Jenisch Vevey, affirms his status as a recognized artist of his period.

It is perhaps most accurate to see Otto Vautier as a skilled and dedicated artist who navigated the artistic currents of his time with integrity. He built upon the strong academic foundation of his Düsseldorf upbringing, particularly in his genre scenes, while also showing a willingness to explore more personal or symbolic themes, especially after his move to Geneva. His contribution lies in his consistent production of well-crafted works that captured aspects of contemporary life, portraiture, and the enduring human figure.

While he may not have been a radical innovator on the scale of a Picasso or a Matisse, or achieved the national icon status of a Hodler, Otto Vautier represents an important strand of European art at the turn of the 20th century – an artist who valued craftsmanship, narrative, and human connection, adapting traditional skills to a changing world. His dual German-Swiss identity further enriches his story, placing him at a crossroads of cultural influences.

Conclusion

Otto Vautier's life (1863-1919) spanned a period of profound artistic change. Born into the heart of the Düsseldorf School's academic tradition through his father, Benjamin Vautier, he absorbed its lessons of meticulous realism and narrative genre painting. His subsequent career, particularly his active years in Geneva, saw him develop a diverse body of work that included evocative depictions of rural life, sensitive portraits, and explorations of the female form, alongside forays into more symbolic imagery.

Works such as Old Woman and Boy Resting, Die Freuden der Zukunft, and Les Bas bleus showcase his technical skill across various media and his engagement with different thematic concerns. He operated within a rich artistic ecosystem, contemporary to figures ranging from the established genre painters of Germany like Ludwig Knaus and Franz von Defregger, to the transformative Swiss artists like Ferdinand Hodler and Félix Vallotton, and the broader European movements of Symbolism and early Modernism.

While critical reception has varied, Vautier remains a noteworthy artist whose work reflects both the enduring appeal of traditional genre painting and an individual artist's response to the evolving cultural landscape of his time. His legacy is that of a dedicated craftsman and a keen observer of humanity, contributing to the rich tapestry of Swiss and German art at a pivotal moment in history.