Edouard Jeanmaire (1847-1916) stands as a significant figure in Swiss art history, particularly celebrated for his intimate and realistic portrayals of the Jura region, its landscapes, people, and way of life. Active during a transformative period in European art, Jeanmaire carved a distinct niche for himself, earning the affectionate title "peintre du Jura" (Painter of the Jura). His work provides a valuable window into the cultural identity and natural beauty of this unique Swiss canton during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, balancing traditional realism with subtle nods towards emerging modern sensibilities.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in 1847 in La Chaux-de-Fonds, a heartland city of the Neuchâtel Jura known for its watchmaking industry and distinct landscape, Edouard Jeanmaire grew up immersed in the environment that would become the central focus of his artistic career. While detailed records of his earliest training are not extensively documented, it is typical for artists of his time and region to have sought initial instruction locally, perhaps in Neuchâtel or Geneva, before potentially venturing to larger art centers like Paris or Munich for further studies. Regardless of his formal path, his deep connection to the Jura's rolling hills, dense forests, and pastoral life was established early on.

His formative years coincided with the dominance of Realism across Europe, a movement championed by artists like Gustave Courbet in France. This emphasis on depicting the world truthfully, without idealization, clearly resonated with Jeanmaire. He developed a keen eye for observation and a technical skill dedicated to capturing the textures, light, and atmosphere of his surroundings. His chosen subjects – the rugged terrain, the hardy flora, the working people, and the essential farm animals – reflect a commitment to representing the authentic character of his homeland.

Thematic Focus: Capturing the Soul of the Jura

Jeanmaire's oeuvre is intrinsically linked to the Swiss Jura. He dedicated his career to exploring its multifaceted identity through his canvases. His landscapes are more than mere topographical records; they convey a sense of place, capturing the specific quality of light filtering through pine forests, the vastness of snow-covered plateaus, or the gentle undulations of pastureland under changing skies. He possessed a remarkable ability to render the atmospheric conditions specific to the region, from crisp winter mornings to hazy summer afternoons.

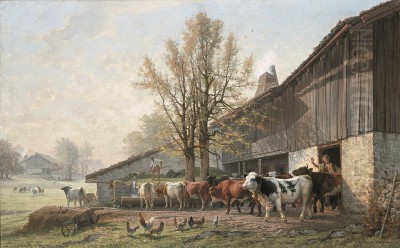

Beyond landscapes, Jeanmaire was a sensitive chronicler of rural life. His paintings often feature the inhabitants of the Jura – farmers, herders, and women engaged in daily tasks. These figures are depicted with dignity and realism, integrated naturally into their environment. He avoided romanticizing rural poverty, instead focusing on the quiet resilience and connection to the land that characterized the region's traditional lifestyle. His interest extended to the animals that were integral to the Jura's agricultural economy and cultural identity.

Goats and, notably, cows feature prominently in his work. The Swiss cow, often depicted with its characteristic horns and bell, was becoming a national symbol during this period, representing pastoral ideals, prosperity, and the country's alpine heritage. Jeanmaire's portrayals of these animals are far from generic; they are individualized studies, showcasing his understanding of their anatomy and behaviour. Some accounts mention detailed depictions, even placing cows in unexpected settings like deep water, highlighting his observational skills and perhaps a touch of narrative interest. These depictions resonated deeply within Switzerland, contributing to the visual culture surrounding national identity.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Edouard Jeanmaire's primary artistic language was Realism. He adhered to careful observation and accurate representation, focusing on details of form, texture, and light. His brushwork, particularly in his earlier works, is often precise, aiming to convey the material reality of his subjects – the rough bark of a pine tree, the coarse wool of a sheep, the solidity of a stone farmhouse. His palette was generally naturalistic, reflecting the earthy tones and verdant greens of the Jura landscape, punctuated by the whites of snow or the colours of changing seasons.

However, Jeanmaire was not merely a passive recorder of reality. His compositions are thoughtfully constructed, often emphasizing harmony and balance. There's a quietude and contemplative quality to many of his scenes. Sources also suggest an innovative approach to materials and techniques. He reportedly experimented with combinations like minerals, pencil, and coloured pigments on paper, suggesting an interest in achieving specific textural and chromatic effects beyond traditional oil painting.

Furthermore, an interesting aspect noted is his consideration of the picture frame as an integral part of the artwork itself. This idea, aligning with the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) explored by Symbolist and Art Nouveau artists, was quite forward-thinking for the early 20th century. It suggests Jeanmaire was aware of broader artistic currents and sought a unified aesthetic experience, moving beyond the purely representational function of painting. This attention to presentation hints at a decorative sensibility coexisting with his realism.

Travels and Evolving Perspectives

While deeply rooted in the Jura, Jeanmaire did not remain entirely confined to his native region. A significant journey undertaken later in his career, around 1912, took him to Norway and the remote Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic. This expedition exposed him to dramatically different landscapes – stark, icy terrains, dramatic fjords, and unique light conditions. Such experiences often profoundly impact artists, challenging their established ways of seeing and working.

Sources indicate that these travels prompted Jeanmaire to incorporate more "stylized" elements into his landscape painting. This suggests a potential shift or evolution in his style during his later years. Perhaps influenced by the raw, elemental nature of the Arctic or by contemporary art movements like Symbolism or Post-Impressionism, which were gaining traction, he may have moved towards simplification of forms, heightened colour, or a more expressive rendering of nature's moods. This evolution reflects a common trajectory for artists of his generation, navigating the transition from 19th-century realism towards the diverse experiments of modern art.

Jeanmaire in the Context of Swiss Art

To fully appreciate Edouard Jeanmaire's contribution, it's essential to place him within the vibrant context of Swiss art at the turn of the 20th century. This was a period of significant artistic activity and debate in Switzerland, marked by a desire to define a distinct national artistic identity while engaging with international trends.

The towering figure in Swiss art during Jeanmaire's active years was undoubtedly Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918). Hodler's powerful style, evolving from Realism through Symbolism to his unique "Parallelism," set a high benchmark. While perhaps not reaching Hodler's level of international fame or radical innovation, Jeanmaire shared Hodler's deep connection to the Swiss landscape and its people. Both artists contributed, in their distinct ways, to the visual construction of Swiss identity.

Jeanmaire's focus on rural life and genre scenes connects him to Albert Anker (1831-1910), arguably Switzerland's most beloved painter of everyday life. Anker's detailed and empathetic portrayals of village communities set a precedent for genre painting that Jeanmaire continued, albeit with a specific focus on the Jura.

Other important contemporaries whose work provides context include Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933), father of Alberto, who embraced Post-Impressionist colour and light; his cousin Augusto Giacometti (1877-1947), a pioneer of abstract art through colour; and Cuno Amiet (1868-1961), another key figure associated with vibrant colour and Post-Impressionist influences, often linked to the Pont-Aven school.

The sharp, sometimes unsettling realism and graphic sensibility of Félix Vallotton (1865-1925), associated with the Nabis group in Paris but Swiss by birth, offers a contrasting modern approach. Meanwhile, artists like Ernest Biéler (1863-1948), associated with the Savièse school, explored decorative styles and themes rooted in Valais traditions, showing another facet of regional artistic identity. Earlier landscape realists like Robert Zünd (1827-1909) and painters of Lake Geneva like François Bocion (1828-1890) represent the tradition Jeanmaire built upon. Even the influence of Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899), though primarily active in the Italian and Austrian Alps, was felt in Switzerland for his monumental depictions of alpine life using Divisionist techniques. Figures like Gustave Castan (1823-1892) and Charles Giron (1850-1914) were also prominent landscape and portrait painters of the era.

Jeanmaire navigated this complex landscape. He remained largely committed to realism but was not immune to the changes around him, as evidenced by his later stylistic explorations and interest in presentation (the frame). He represents a strand of Swiss art that valued regional identity, careful observation, and traditional craftsmanship, while subtly acknowledging the shifting artistic climate.

Notable Works and Legacy

Pinpointing specific "masterpieces" by Jeanmaire can be challenging, as his reputation rests more on the consistent quality and thematic focus of his overall output rather than a few iconic, widely reproduced works. However, titles mentioned in relation to his work, such as Matin de Printemps (Spring Morning) and Matin d'Hiver (Winter Morning), clearly point to his dedication to capturing the Jura landscape across different seasons and times of day. These titles evoke the atmospheric sensitivity central to his art. It is crucial to note, however, that these generic titles have also been used by other, sometimes more famous, artists for entirely different works (e.g., compositions by Lili Boulanger, paintings by Édouard Manet or Camille Pissarro). Care must be taken not to confuse Jeanmaire's potential works bearing these names with others. His paintings are best understood as variations on his core themes: Jura forests, pastures, farmsteads, and the animals and people inhabiting them.

His contribution extended beyond easel painting. His work as an illustrator, notably for a Geneva educational guide (potentially the Geneva Guide or Geneva Educational Centre publication mentioned in sources), demonstrates his engagement with the broader cultural life of the region and his recognized skill. Such commissions often helped artists disseminate their style and gain wider recognition within their communities.

Jeanmaire's legacy lies primarily in his role as the quintessential "Painter of the Jura." He captured the spirit of a region at a specific moment in time, preserving its landscapes and traditions through his art. His works are held in Swiss collections, with the Château de Valangin near Neuchâtel noted as holding a significant number of his paintings, ensuring his contribution is preserved and accessible. While he may not have achieved the international renown of Hodler or the avant-garde status of others, his dedication to his chosen subject matter and his skillful realism earned him a lasting place within Swiss art history.

Recognition and Historical Evaluation

During his lifetime, Edouard Jeanmaire achieved considerable recognition within Switzerland. His designation as the "Painter of the Jura" was not merely descriptive but a title of respect, acknowledging his authentic connection to and representation of the region. His participation in significant exhibitions, including the prestigious Paris Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) of 1900, indicates that his work was deemed worthy of representing Swiss art on an international stage, even if it didn't spark widespread foreign acclaim.

His art resonated with a public that valued depictions of national landscapes and traditional life, themes that were particularly important during a period of national consolidation and identity formation in Switzerland. His realistic style was accessible and appreciated for its perceived honesty and connection to the tangible world. The fact that his subjects, like the Swiss cow, were intertwined with the country's economic success and cultural symbolism further cemented his relevance.

Historically, Jeanmaire is evaluated as a skilled and dedicated regionalist painter. He represents an important aspect of Swiss art that focused on documenting and celebrating the specific character of the nation's diverse cantons. While art history often prioritizes radical innovators, figures like Jeanmaire are crucial for understanding the broader artistic landscape and the cultural values of their time. His work offers a counterpoint to the more dramatic styles of Symbolism or early Modernism, showcasing the enduring appeal of realism and the deep connection between art and place.

Conclusion

Edouard Jeanmaire remains a respected figure in Swiss art, celebrated for his lifelong dedication to portraying the Jura region. As the "peintre du Jura," he created a body of work characterized by sensitive realism, careful observation, and a deep affection for his homeland's landscapes, people, and traditions. Active during a period of artistic transition, he largely remained true to his realist roots while showing awareness of contemporary ideas through subtle stylistic evolutions and an innovative approach to presentation. His paintings, particularly those featuring the iconic Swiss cow and the distinctive Jura terrain, contributed to the visual culture of Switzerland and continue to offer valuable insights into the region's identity at the turn of the 20th century. Though perhaps overshadowed internationally by contemporaries like Hodler, Jeanmaire's consistent output and regional focus secure his legacy as a significant chronicler of the Swiss spirit.