Paolo Veneziano stands as a monumental figure in the annals of art history, widely recognized as the most significant Venetian painter of the 14th century and a foundational force in the development of the Venetian School. Active during a transformative period, his work masterfully bridged the waning Byzantine artistic traditions with the burgeoning Gothic sensibilities arriving from the West. His extensive workshop, often including his talented sons, produced a remarkable body of work that adorned churches and private chapels, shaping the visual and spiritual landscape of Venice and its territories. This article delves into the life, style, major works, and enduring legacy of this pivotal artist, often hailed as the first truly individual painter to emerge in Venice.

The Mists of Origin: Unraveling Paolo's Early Life

The precise details of Paolo Veneziano's early life, particularly his birth year, remain shrouded in the mists of time, a common challenge for art historians studying figures from the Trecento. Scholarly consensus and documentary evidence suggest he was active as a painter from at least 1333 until shortly before his death, which is more confidently placed around 1362. One of the earliest mentions of Paolo comes from a document dated 1339, which refers to him as the son of a painter named Martino da Venezia. This familial connection to the craft suggests an upbringing immersed in an artistic environment, likely apprenticing in his father's workshop from a young age.

Several theories exist regarding his birth year. Some scholars propose a date around 1295, which would align with a mature artist producing significant works by the 1330s. Others suggest a birth closer to 1300. A later date, around 1333, has also been posited by some, though this would imply an extraordinarily precocious talent given the date of his first signed works. The most widely accepted timeframe places his birth in the final years of the 13th century or the very beginning of the 14th century. This would allow for a substantial period of training and development before his documented activity.

His first signed and dated work, the "Dormition of the Virgin" polyptych (now in Vicenza), is inscribed with the year 1333. This piece already showcases a distinct artistic personality, one that, while rooted in Byzantine conventions, demonstrates a nascent understanding of Gothic expressiveness. The existence of such a sophisticated work implies that by this date, Paolo was already an established master with his own workshop. The very name "Veneziano" (meaning "the Venetian") indicates his strong identification with the city that would become the epicenter of his artistic endeavors.

Venice in the Trecento: A Crucible of Cultures

To understand Paolo Veneziano's art, one must first appreciate the unique cultural and artistic milieu of 14th-century Venice. La Serenissima, as the Venetian Republic was known, was a thalassocracy, a maritime empire whose wealth and influence were built on trade. Its strategic location at the crossroads of East and West made it a vibrant hub where Byzantine, Islamic, and Western European cultures intermingled. This constant influx of diverse influences profoundly shaped Venetian art.

For centuries, Venetian art had been heavily indebted to Byzantine models. The city's historical ties to Constantinople, particularly after the Fourth Crusade in 1204 which brought a wealth of Byzantine treasures (including the famed horses of St. Mark's) to Venice, reinforced this artistic orientation. Mosaics, icons, and illuminated manuscripts in the Byzantine style were prevalent. Artists like Cimabue in Florence and Duccio di Buoninsegna in Siena were also working within an Italo-Byzantine tradition, but Venice's connection was perhaps the most direct and prolonged.

However, by the 14th century, new artistic currents were flowing into Italy. The revolutionary naturalism of Giotto di Bondone in Florence and Padua was beginning to challenge the stylized conventions of Byzantine art. Simultaneously, the elegant and expressive forms of Gothic art, particularly from France and Northern Europe, were gaining traction across the Italian peninsula, influencing artists like Simone Martini of Siena. Venice, while somewhat insulated by its unique cultural position, was not immune to these changes. Paolo Veneziano emerged at this critical juncture, uniquely positioned to synthesize these diverse strands.

Patronage in Venice was robust, driven by the state, the powerful Scuole (confraternities), wealthy merchant families, and numerous religious orders. The Doge, the elected head of state, was a significant patron, as evidenced by commissions for the Doge's Palace. Churches and monasteries required altarpieces, devotional panels, and narrative cycles, providing ample opportunities for artists like Paolo.

A Synthesis of Styles: Byzantine Grandeur and Gothic Grace

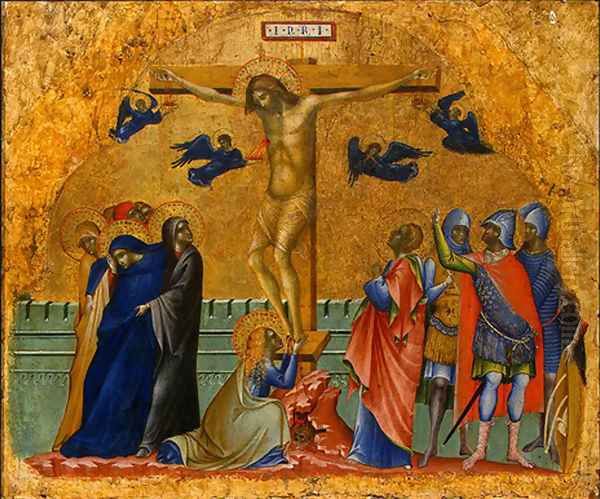

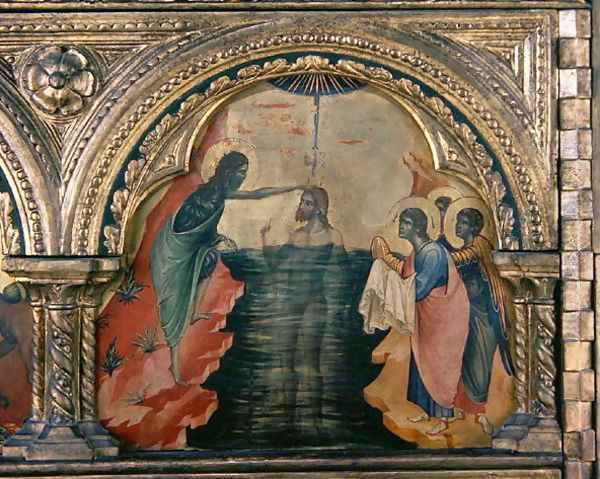

Paolo Veneziano's artistic genius lies in his ability to forge a distinctive personal style from the prevailing artistic currents. He did not simply replicate Byzantine forms, nor did he fully embrace the nascent naturalism of Giotto or the courtly elegance of the International Gothic. Instead, he created a harmonious blend, retaining the solemn grandeur and rich decorative qualities of Byzantine art while infusing it with a new sense of narrative dynamism, emotional resonance, and a more refined observation of the natural world characteristic of Gothic art.

Key Byzantine elements in Paolo's work include the extensive use of gold leaf backgrounds, which create a sense of divine, timeless space. Figures often possess an iconic frontality and a hierarchical scale, where more important figures are depicted larger. His color palette is rich and luminous, reminiscent of Byzantine enamels and mosaics, with deep blues, vibrant reds, and shimmering golds. The linearity of his figures, with their carefully delineated drapery folds, also harks back to Byzantine traditions. He often employed established iconographic types for subjects like the Madonna and Child or scenes from the life of Christ.

However, Paolo tempered this Byzantine austerity with Gothic sensibilities. His figures, while still stylized, exhibit a greater degree of human emotion and interaction. Faces are more individualized, and gestures convey a wider range of feelings, from tender maternal love to profound grief. Draperies, though often elaborate, begin to suggest the form of the body beneath and fall in more naturalistic, albeit still elegant, cascades. There is an increased interest in narrative clarity and storytelling, with scenes populated by more figures and incorporating greater detail in settings and accessories. This narrative impulse is a hallmark of Gothic art, which sought to make religious stories more accessible and relatable to the faithful. Artists like Pietro Lorenzetti and Ambrogio Lorenzetti in Siena were also exploring this narrative potential within a broadly similar stylistic framework.

The Workshop of Paolo Veneziano: A Family Enterprise

Like most successful artists of his time, Paolo Veneziano headed a thriving workshop. This was not merely a place of production but also a center of training. The workshop system allowed masters to undertake large-scale commissions by employing assistants and apprentices who would learn the craft by participating in various stages of the creative process, from preparing panels and grinding pigments to painting less critical areas of a composition.

Paolo's workshop appears to have been a significant family affair. His sons, Luca Veneziano and Giovanni Veneziano, were both painters who collaborated extensively with their father. Their names often appear alongside Paolo's in signed works, particularly in his later period. For instance, the magnificent "Coronation of the Virgin" (1358, Frick Collection, New York) is signed by Paolo and his son Giovanni. The "Pala Feriale" (weekday altarpiece) for St. Mark's Basilica, commissioned in 1345 by Doge Andrea Dandolo to cover the precious Pala d'Oro on non-festive days, was a collaborative effort involving Paolo and his sons Luca and Giovanni. This monumental work, depicting scenes from the life of St. Mark and other saints, showcased the workshop's capacity to handle large and prestigious commissions.

The involvement of his sons ensured the continuity of his style and workshop practices. While Luca and Giovanni developed their own artistic personalities, their work remained deeply indebted to their father's teachings. Other assistants, whose names are not always recorded, would have also contributed to the workshop's output. This collaborative approach was standard practice and allowed for a prolific production of altarpieces, polyptychs, and devotional panels that were in high demand. The consistency of quality and style across works attributed to Paolo and his workshop attests to his strong guiding hand and the effective training provided.

Masterpieces of Luminous Devotion

Paolo Veneziano's oeuvre is characterized by its devotional intensity and exquisite craftsmanship. His works, typically executed in egg tempera on wooden panels, radiate with vibrant colors and the gleam of gold.

One of his most celebrated works is the "Coronation of the Virgin" (1358), now in the Frick Collection, New York. Co-signed with his son Giovanni, this panel is a symphony of color and pattern. Christ, seated on an elaborate throne, places a crown on the head of the Virgin Mary, surrounded by a celestial choir of angels playing musical instruments. The figures are elongated and elegant, their robes rendered with intricate gold brocade patterns (damascening) that catch the light. The expressions are serene and dignified, conveying the solemnity and joy of the heavenly event. The work exemplifies Paolo's late style, where Byzantine opulence is seamlessly blended with Gothic grace.

The "Pala Feriale" (1345), though now dispersed and partially lost, was a landmark commission. The surviving panels, such as those in the St. Mark's Museum, demonstrate Paolo's narrative skill and his ability to organize complex compositions. These scenes, intended for daily viewing, were crucial in disseminating his style and reinforcing the religious narratives central to Venetian civic and spiritual life.

Numerous polyptychs (multi-paneled altarpieces) are attributed to Paolo and his workshop. The Vicenza Polyptych (1333), depicting the Dormition of the Virgin flanked by saints, is his earliest signed and dated work. It already shows his characteristic blend of Byzantine iconographic formulas with a more animated and expressive treatment of figures. Another significant example is the polyptych in the Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, often referred to as the "Santa Chiara Polyptych," which features a central Madonna and Child with saints in flanking panels and scenes from the life of Christ in the predella. These complex altarpieces were designed to provide multiple focal points for devotion and instruction.

Individual panels of the "Madonna and Child" were also a staple of his production. Examples can be found in major museums worldwide, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. and the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. These panels, often intended for private devotion, showcase Paolo's ability to convey the tender relationship between mother and child within a framework of divine majesty. The Virgin is typically depicted as a regal Queen of Heaven, yet her interaction with the Christ Child is imbued with human warmth.

Other notable works include panels depicting individual saints, such as "Michael the Archangel," where the warrior archangel is presented with a combination of divine authority and dynamic energy. His ability to render intricate details, from the feathers of angels' wings to the patterns on textiles, was remarkable.

The Artisan's Craft: Technique and Materials

Paolo Veneziano worked primarily in egg tempera on wooden panels, the dominant painting technique in Italy before the widespread adoption of oil painting in the later 15th century. Egg tempera involves mixing pigments with egg yolk (and sometimes a little water or vinegar) to create a fast-drying, durable paint. This medium allows for precise detail and luminous color but requires meticulous application, often in thin layers or with fine brushstrokes (hatching and cross-hatching) to achieve modeling and tonal variation.

The preparation of the wooden panels was a crucial first step. Poplar wood was commonly used. The panel would be smoothed and then covered with multiple layers of gesso (a mixture of animal glue and gypsum or chalk), creating a smooth, white, absorbent ground ideal for tempera painting and gilding.

Gilding was an integral part of Paolo's art, reflecting the Byzantine love for celestial radiance. Gold leaf would be applied to areas designated for backgrounds, halos, or decorative patterns on garments. This was a skilled process involving the application of an adhesive layer (bole, a reddish clay mixture, was often used for burnished gold) onto which the thin sheets of gold leaf were carefully laid. The gold could then be burnished to a high sheen or tooled with punches and incised lines to create intricate patterns (as seen in the damascening on robes or the elaborate designs in halos).

Paolo's mastery of these traditional techniques, combined with his innovative stylistic synthesis, resulted in works of enduring beauty and spiritual power. The brilliance of his colors, the richness of his gold, and the precision of his draftsmanship are testaments to his exceptional skill as a craftsman.

Paolo and His Peers: The Artistic Landscape of the Trecento

While Paolo Veneziano was the pre-eminent painter in Venice during his lifetime, he operated within a broader Italian artistic context. His sons, Luca and Giovanni Veneziano, were his closest collaborators and stylistic heirs. His father, Martino da Venezia, represents the preceding generation of Venetian painters, likely working in a more purely Byzantine mode.

The most significant Venetian painter to follow directly in Paolo's footsteps was Lorenzo Veneziano. Active from the 1350s to the 1370s, Lorenzo likely trained in Paolo's workshop or was profoundly influenced by his style. Lorenzo further developed the Gothic elements in Venetian painting, imbuing his figures with even greater elegance and expressiveness, moving towards the International Gothic style.

Other Venetian painters active during or shortly after Paolo's time include Nicoletto Semitecolo, known for his narrative panels, and Guariento di Arpo, a Paduan artist who was also active in Venice and worked on major commissions in the Doge's Palace, notably the large "Coronation of the Virgin" fresco (later replaced by Tintoretto's "Paradise" after a fire). Guariento's style, while also blending Byzantine and Gothic elements, had a distinct character, perhaps more influenced by mainland Italian developments.

Beyond Venice, the towering figure of Giotto di Bondone (d. 1337) had revolutionized Italian painting earlier in the century. While Giotto's direct influence on Paolo is debated, his emphasis on human emotion and three-dimensional form had a ripple effect throughout Italy. In Siena, artists like Duccio di Buoninsegna (d. c. 1319), Simone Martini (d. 1344), and the brothers Pietro Lorenzetti (d. c. 1348) and Ambrogio Lorenzetti (d. c. 1348) were creating their own sophisticated syntheses of Byzantine tradition and Gothic innovation. Their work, particularly Simone Martini's, with its courtly elegance and refined linearity, shared some affinities with the Gothic aspects of Paolo's style, though developing along distinct regional lines. The earlier master Cimabue (d. c. 1302) also represents the rich Italo-Byzantine heritage from which these Trecento masters emerged. Paolo's art, therefore, can be seen as Venice's unique response to the artistic transformations sweeping across the Italian peninsula.

Enduring Legacy: Shaping the Venetian School

Paolo Veneziano's impact on the course of Venetian art was profound and lasting. He is rightly considered the "founder" of the Venetian School, not in the sense of a formal academy, but as the first major artistic personality to establish a distinctly Venetian style that moved beyond strict adherence to Byzantine models. His workshop became a dominant force, disseminating his style through numerous commissions and training the next generation of painters.

His synthesis of Byzantine opulence with Gothic expressiveness provided a foundation upon which later Venetian artists would build. While the International Gothic style, exemplified by artists like Gentile da Fabriano and Pisanello (who both worked in Venice in the early 15th century), would subsequently flourish, Paolo's legacy of rich color, decorative splendor, and a certain lyrical quality remained embedded in the Venetian artistic DNA.

The emphasis on color and light, already evident in Paolo's gilded backgrounds and vibrant pigments, would become a defining characteristic of Venetian painting throughout the Renaissance. Later masters of the Venetian School, such as the Bellini family (Jacopo, Gentile, and Giovanni Bellini), Vittore Carpaccio, and culminating in the High Renaissance giants Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, all inherited, in a sense, this foundational Venetian sensibility that Paolo helped to forge. Though their styles evolved dramatically with the advent of Renaissance humanism, perspective, and oil painting techniques, the Venetian preoccupation with color, atmosphere, and a certain sensuous beauty can be traced back to these early masters.

Paolo's influence also extended beyond Venice itself, to other centers along the Adriatic coast and into regions like Bologna, where his altarpieces were sometimes exported or his style emulated by local artists.

Reappraising Paolo Veneziano: A Modern Perspective

In modern art historical scholarship, Paolo Veneziano is recognized as a pivotal figure in the transition from medieval to early Renaissance art in Venice. His ability to innovate while respecting tradition marks him as a key artist of the Trecento. While his fame might be less widespread internationally compared to Florentine contemporaries like Giotto, his importance within the Venetian context is undeniable.

Challenges remain for scholars, particularly in definitively attributing works to Paolo himself versus his workshop or followers, and in precisely dating certain pieces. However, ongoing research and technical analysis continue to shed light on his methods and collaborations.

His works continue to captivate viewers with their spiritual intensity, their dazzling color and gold, and their unique blend of solemnity and tenderness. They offer a precious window into the vibrant artistic and religious life of 14th-century Venice, a city on the cusp of becoming one of the great artistic centers of the Renaissance.

Conclusion: The First Light of Venetian Painting

Paolo Veneziano was more than just a skilled painter; he was an innovator who laid the critical groundwork for the Venetian School of painting. Operating at a cultural crossroads, he skillfully navigated the rich heritage of Byzantine art and the emerging dynamism of the Gothic style, forging a new artistic language that was uniquely Venetian. His workshop, a hub of creativity and training often involving his own sons, produced an impressive array of altarpieces and devotional images that adorned the churches and homes of La Serenissima. Through his luminous colors, expressive figures, and masterful command of technique, Paolo Veneziano not only dominated the art scene of 14th-century Venice but also cast a long shadow, influencing generations of artists and helping to define the enduring characteristics of Venetian art for centuries to come. He remains a testament to the transformative power of an individual artistic vision in shaping a city's cultural identity.