Andrea Bonaiuti, also known as Andrea di Bonaiuto or Andrea da Firenze, stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 14th-century Italian art. Active primarily in Florence and Pisa, he was a painter whose work, particularly in the medium of fresco, captured the religious fervor and intellectual currents of his time. His legacy is most prominently cemented by the extensive and complex decorative program of the Spanish Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his near-contemporaries or immediate successors, Bonaiuti's contributions were vital to the artistic developments of the Trecento, bridging the monumental impact of Giotto with the evolving styles that would eventually blossom into the Early Renaissance.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Andrea Bonaiuti is believed to have been born in Florence around 1325. This places his formative years in a city still reeling from, yet artistically invigorated by, the revolutionary achievements of Giotto di Bondone, who had died in 1337. The artistic scene was rich, with Giotto's followers like Taddeo Gaddi and Maso di Banco continuing to explore naturalism and narrative depth. Bonaiuti's exact training remains undocumented, a common reality for many artists of this period. However, his style suggests an absorption of these Giottesque principles, alongside influences from the more decorative and elegant Sienese school, particularly the work of artists like Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti brothers, Ambrogio and Pietro.

A pivotal event in Bonaiuti's early life, and indeed for all of Europe, was the Black Death. He is recorded as having survived the devastating plague that swept through Florence in 1348, an event that decimated the population and profoundly impacted the city's social, economic, and religious fabric. This experience undoubtedly shaped the worldview of those who lived through it, often leading to an intensified religious piety, which in turn fueled artistic commissions for churches and private devotion.

By 1346, Andrea Bonaiuti had achieved a level of professional standing, as evidenced by his enrollment in the Florentine Arte dei Medici e Speziali (Guild of Doctors and Apothecaries). This was the guild to which painters typically belonged in Florence, a testament to their status as skilled craftsmen. From 1351, records indicate he was residing in the Santa Maria Novella quarter of Florence, an area dominated by the great Dominican basilica that would later house his most famous work.

The Pisan Interlude

Before undertaking his magnum opus in Florence, Bonaiuti spent a significant period working in the nearby maritime republic of Pisa. Documents suggest he was active there from approximately 1355 for about a decade, returning to Florence around 1365. Pisa, with its own rich artistic traditions and monumental sites like the Camposanto Monumentale (Monumental Cemetery), offered ample opportunities for artists.

During his time in Pisa, Bonaiuti is credited with frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Saint Rainerius (San Ranieri), the patron saint of Pisa. These were likely executed in the Camposanto or a church dedicated to the saint, such as San Ranierino. This Pisan period would have exposed him to different artistic currents and allowed him to hone his skills in large-scale narrative fresco painting, a crucial experience that would inform his later work in Florence. The Camposanto itself was a major center for fresco decoration, featuring works by artists like Taddeo Gaddi and, later, the enigmatic Buffalmacco (Buonamico di Martino), whose dramatic "Triumph of Death" frescoes would have been a powerful presence.

The Florentine Context: Art, Faith, and Patronage in the Trecento

Upon his return to Florence around 1365, Bonaiuti found a city that continued to be a vibrant center for the arts, despite the recurring waves of plague and political instabilities. The Dominican and Franciscan orders were powerful patrons, commissioning extensive fresco cycles to instruct the laity and glorify their respective orders. Artists like Andrea Orcagna (Andrea di Cione) and his brothers, Nardo di Cione and Jacopo di Cione, were dominant figures, known for their solemn and hieratic style, which some scholars see as a reaction to the trauma of the Black Death, a move towards a more iconic and less naturalistic representation. Giovanni da Milano, another contemporary, brought a Lombard tenderness and richness of color to the Florentine scene. Agnolo Gaddi, son of Taddeo Gaddi, was also emerging as a prolific painter, carrying on the Giottesque narrative tradition.

It was within this environment that Andrea Bonaiuti received the commission for the Spanish Chapel. The patronage system was crucial; wealthy families, confraternities, and religious orders fueled artistic production. The Dominicans, in particular, were known for their intellectualism and their role as defenders of orthodoxy, themes that would be central to Bonaiuti's work for them.

The Spanish Chapel (Cappellone degli Spagnoli): A Monumental Achievement

Andrea Bonaiuti's most celebrated and enduring work is the complete fresco decoration of the Chapter House of Santa Maria Novella, later known as the Cappellone degli Spagnoli (Spanish Chapel). This vast undertaking, executed between 1365 and 1368, was commissioned by Mico (Buonamico) Guidalotti as his funerary chapel and as a chapter house for the Dominican friars. The chapel is a veritable summa of Dominican theology and a powerful piece of visual propaganda for the Order. Bonaiuti's frescoes cover all the walls and the vault, creating an immersive and didactic environment.

The Vault:

The vault frescoes depict scenes related to Christ's Passion and Resurrection: the Resurrection of Christ, the Ascension, Pentecost, and, notably, Christ Navicella (Christ saving Peter from the sinking boat, a symbol of the Church). These scenes establish the overarching redemptive narrative of the Christian faith.

The Altar Wall (East Wall):

Dominating the altar wall are scenes of Christ's Passion: Christ Carrying the Cross, the Crucifixion, and the Descent into Limbo. These are rendered with a narrative clarity and emotional gravity characteristic of the Giottesque tradition, though Bonaiuti's figures tend to be stockier and his compositions denser than Giotto's. The Crucifixion is particularly grand, a panoramic scene filled with numerous figures expressing a range of emotions.

The Right Wall (South Wall): The Church Militant and Triumphant (Via Veritatis)

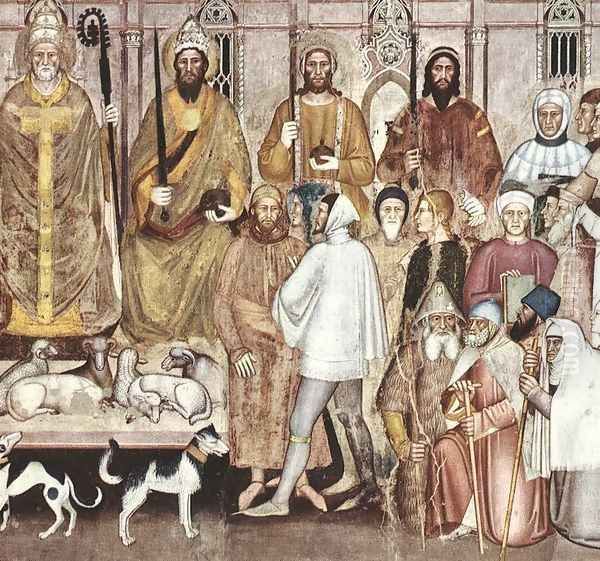

This is perhaps the most famous and iconographically complex wall in the chapel. It is often interpreted as an allegory of the Dominican Order's role in guiding humanity towards salvation – the Via Veritatis or Way of Truth. The composition is divided into earthly and heavenly realms.

Below, the earthly Church is represented by a depiction of what is believed to be Florence Cathedral (though an idealized version), with figures of religious and secular authority, including the Pope (possibly Urban V), the Holy Roman Emperor (possibly Charles IV), and other dignitaries. Dominican friars, recognizable by their black and white habits, are shown preaching, converting heretics (represented by figures turning away or cowering), and guiding the faithful. Black and white dogs (a pun on Domini canes, "hounds of the Lord") are depicted attacking wolves (heretics), symbolizing the Dominicans' role as defenders of the faith.

Above this earthly scene, the Church Triumphant shows Christ in Glory, surrounded by angels and saints, with the saved souls ascending to Paradise. The entire wall is a powerful assertion of the Church's, and specifically the Dominican Order's, indispensable role in the world.

The Left Wall (North Wall): The Triumph of Saint Thomas Aquinas

This wall celebrates the intellectual and theological contributions of the Dominican Order, personified by its most illustrious theologian, Saint Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas is enthroned, holding an open book displaying wisdom, flanked by prophets, evangelists, and allegorical figures of the Virtues and the Liberal Arts. Below him are seated figures representing various branches of knowledge and, significantly, defeated heretics or philosophers whose ideas were considered erroneous, such as Arius, Sabellius, and Averroes, trampled underfoot. This fresco underscores the Dominican emphasis on learning and scholasticism as tools for understanding and defending Christian doctrine. The composition is hierarchical and didactic, clearly laying out the structure of divinely inspired knowledge.

The Entrance Wall (West Wall): Scenes from the Life of Saint Peter Martyr

This wall is dedicated to scenes from the life of Saint Peter Martyr, a 13th-century Dominican friar and inquisitor who was assassinated by heretics. The frescoes depict his preaching, miracles, and martyrdom. His story served as an exemplar of Dominican zeal and sacrifice. These narrative scenes are more straightforwardly biographical than the allegorical compositions on the other walls.

The overall effect of the Spanish Chapel is overwhelming. Bonaiuti skillfully managed the vast surfaces, creating compositions that are both grand in scale and rich in detail. His color palette is vibrant, with strong reds, blues, and greens. While his figures may lack the profound psychological depth of Giotto or the elegant grace of Sienese masters like Simone Martini, they possess a sturdy presence and effectively convey the narrative and allegorical messages. The Spanish Chapel stands as one of the most complete and complex iconographic programs of the 14th century, a testament to Bonaiuti's organizational skills and his ability to translate complex theological concepts into visual form.

Other Attributed Works and Artistic Style

Beyond the Spanish Chapel and the Pisan frescoes, relatively few works are securely attributed to Andrea Bonaiuti. Many works from this period are unsigned, leading to scholarly debate about attributions. Some panel paintings, including smaller triptychs or polyptychs depicting the Madonna and Child with saints, have been associated with his name or his workshop, but often with less certainty than his fresco cycles. The "Small triptych of Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels" mentioned in some sources, possibly influenced by a "Marco dan Poci" (a name not readily identifiable among prominent artists, perhaps a corruption or a very minor local master), would fit into the common devotional imagery of the time.

Bonaiuti's artistic style is characterized by:

Narrative Clarity: He excelled at organizing complex scenes with many figures, ensuring the story or allegorical message was legible.

Didactic Purpose: Much of his work, especially in the Spanish Chapel, was intended to instruct and edify the viewer, reflecting the priorities of his Dominican patrons.

Solid Figural Types: His figures are generally robust and grounded, rather than ethereal or overly elongated. They are expressive in gesture, though perhaps not deeply individualized in facial features.

Rich Coloration: He employed a vibrant palette, which contributes to the visual impact of his frescoes.

Compositional Skill: He managed large wall surfaces effectively, balancing crowded scenes with areas of relative calm, and using architectural elements within the paintings to structure the compositions.

Influence of Giotto and Siena: His work shows a grounding in the Giottesque tradition of weighty figures and narrative focus, but also incorporates a certain decorative quality and attention to detail that may reflect Sienese influences or the broader International Gothic tendencies that were beginning to emerge. Compared to the more austere and sometimes stark monumentality of artists like Andrea Orcagna, Bonaiuti's style can appear more animated and detailed.

He was a master of the fresco technique, which required swift and confident execution on wet plaster. His emphasis on clear outlines and relatively flat application of color is typical of Trecento fresco painting, which prioritized legibility and decorative effect over the illusionistic depth that would become a hallmark of the Renaissance.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Andrea Bonaiuti worked within a dynamic artistic environment. The legacy of Giotto (d. 1337) was still potent, carried on by artists like Taddeo Gaddi (d. c. 1366), who completed the Baroncelli Chapel frescoes in Santa Croce, and Bernardo Daddi (d. 1348), known for his lyrical panel paintings.

The Sienese school, with masters like Simone Martini (d. 1344) and the brothers Pietro Lorenzetti (d. c. 1348) and Ambrogio Lorenzetti (d. c. 1348), offered a contrasting style characterized by elegant lines, refined color harmonies, and a more courtly sensibility. Sienese influence was certainly felt in Florence.

Bonaiuti's direct Florentine contemporaries included the highly influential Cione brothers: Andrea di Cione, known as Orcagna (active c. 1343-1368), who was a painter, sculptor, and architect, and his brothers Nardo di Cione (active c. 1343-1366) and Jacopo di Cione (active c. 1365-1398). Orcagna's Strozzi Altarpiece in Santa Maria Novella is a key work of the period, displaying a more formal and hieratic style. Nardo di Cione's frescoes in the Strozzi Chapel of Santa Maria Novella, depicting the Last Judgment, Paradise, and Hell, are powerful and somewhat severe. Some scholars suggest Bonaiuti may have been influenced by, or even collaborated with, Nardo di Cione, though the exact nature of their relationship is debated.

Other notable Florentine painters of the era include Giottino (active c. 1324-1369), whose Pietà (now in the Uffizi) shows a profound emotional intensity, and Giovanni da Milano (active in Florence c. 1346-1369), who brought a Northern Italian richness and tenderness to his work, notably in the Rinuccini Chapel in Santa Croce. Agnolo Gaddi (active c. 1369-1396), son of Taddeo, became one of the most prolific fresco painters in Florence towards the end of the century, known for his extensive narrative cycles, such as the Legend of the True Cross in the choir of Santa Croce. These artists, along with Bonaiuti, shaped the visual culture of mid-to-late Trecento Florence.

Unresolved Questions and Scholarly Debates

Despite his significant contributions, aspects of Andrea Bonaiuti's life and work remain subjects of scholarly discussion. The precise chronology of some of his works, particularly those outside the well-documented Spanish Chapel, can be uncertain. The attribution of unsigned panel paintings to his hand or workshop is often debated, as stylistic analysis can be subjective.

One intriguing aspect mentioned in some accounts is his financial situation. Despite the prestige of commissions like the Spanish Chapel, it is said that he died in 1379 leaving a relatively modest estate to his wife and children. This could reflect the economic realities for artists of the time, where even major commissions did not always translate into substantial personal wealth, or perhaps it points to personal circumstances or spending habits about which we know little.

The extent of his direct influence on subsequent generations of painters is also a matter for consideration. While the Spanish Chapel remained a prominent monument, the artistic tide in Florence would soon turn with the emergence of the International Gothic style, followed by the groundbreaking innovations of Early Renaissance masters like Masaccio, Filippo Brunelleschi, and Donatello in the early 15th century. These artists, born after Bonaiuti's death or in his final years, would set painting on a new course. However, Bonaiuti's work remains a crucial example of the artistic and intellectual concerns of the late Trecento.

The interpretation of the complex iconography in the Spanish Chapel continues to fascinate art historians. While the general themes are clear, the specific identification of all figures and the nuanced meanings embedded in the allegories can still spark debate. The chapel's frescoes are a rich field for understanding Dominican theology, 14th-century Florentine society, and the role of art as a vehicle for religious instruction and institutional promotion.

Legacy and Conclusion

Andrea Bonaiuti da Firenze died in 1379. He left behind a body of work that, while perhaps not as extensive as some of his contemporaries, is marked by a monumental achievement in the Spanish Chapel. These frescoes are invaluable for understanding the religious life, theological preoccupations, and artistic capabilities of 14th-century Florence. They represent a high point of didactic, narrative fresco painting in the service of a powerful religious order.

Bonaiuti was an artist of his time, skillfully synthesizing the artistic currents he inherited, particularly the Giottesque tradition, with the specific demands of his patrons. He navigated the challenges of large-scale composition with considerable ability, creating works that were both visually engaging and intellectually rich. While the artistic innovations of the Quattrocento would soon transform Florentine art, Andrea Bonaiuti's contribution remains a significant chapter in the story of Italian painting, a testament to the enduring power of art to convey complex ideas and shape a city's spiritual landscape. His work in the Spanish Chapel, in particular, ensures his place as a key master of the Florentine Trecento.