Paul Mathey (1844-1929) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant Parisian art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A French national, Mathey distinguished himself as a painter, a highly skilled printmaker, particularly in etching, and even a sculptor. His career spanned a period of immense artistic change, from the dominance of the Salon and academic traditions to the rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Mathey, while rooted in a realist tradition, navigated this evolving landscape with a distinct personal style, particularly evident in his insightful portraits and atmospheric landscapes.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Born in Paris in 1844, Paul Mathey was immersed in the artistic capital of the world from his earliest years. The city itself was a crucible of creative energy, and it was here that Mathey would receive his formal artistic training. He sought instruction from several notable masters of the time, each contributing to the development of his technical skills and artistic vision.

His tutelage under Léon Cogniet (1794-1880) was particularly formative. Cogniet was a highly respected painter of historical and portrait subjects, himself a product of the Neoclassical school of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, but also known for his more Romantic sensibilities in some works. Cogniet's studio was a prominent training ground, and his emphasis on strong draughtsmanship and compositional structure would have provided Mathey with a solid academic foundation. Cogniet's own career saw him adapt to changing tastes, moving from historical scenes to more intimate portraits, a versatility that Mathey might have observed.

Mathey also studied with Isidore Pils (1813-1875), another significant academic painter. Pils was renowned for his military scenes and religious paintings, often characterized by their dramatic flair and meticulous detail. His work, like Rouget de Lisle Singing La Marseillaise, demonstrated a capacity for capturing patriotic fervor and historical moments, skills that required keen observation and narrative ability. From Pils, Mathey likely honed his ability to depict figures with accuracy and to manage complex compositions.

Further instruction came from Alexis-Joseph Mazerolle (1826-1889), a decorative painter known for his large-scale allegorical and mythological works, often designed for public buildings and private residences. Mazerolle was a master of decorative effect and figural grace, working in a style that blended academic precision with a lighter, more sensuous touch, akin to the Rococo revival. His influence might have encouraged Mathey to consider the aesthetic harmony and elegance in his compositions.

The artist Oury, though less universally documented than Cogniet or Pils, also contributed to Mathey's education. The collective impact of these teachers, each with their distinct specializations within the academic tradition, equipped Mathey with a comprehensive skill set, encompassing strong drawing, compositional understanding, and a sensitivity to both historical subjects and contemporary portraiture. This traditional grounding was crucial for any artist aspiring to succeed in the competitive Parisian art scene of the mid-19th century.

Debut at the Salon and Early Career

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish their careers. Paul Mathey made his debut at the Salon in 1868. This was a significant milestone, marking his entry into the professional art world. To be accepted into the Salon was an achievement in itself, indicating a level of technical proficiency and artistic merit deemed acceptable by the discerning jury.

His early submissions likely included portraits and genre scenes, areas in which he would continue to excel. The Salon of this era was a bustling, crowded affair, with thousands of works vying for attention. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and Alexandre Cabanel were among the reigning stars, championing a polished, academic style. Mathey's work, while rooted in this tradition, would develop its own nuanced character.

The trajectory of Mathey's early career was briefly interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and the subsequent Siege of Paris. Like many of his compatriots, Mathey served in the National Guard during this tumultuous period. This direct experience of conflict and civic duty undoubtedly left an impression, perhaps deepening his understanding of human character and resilience, qualities that could subtly inform his later portraiture. Artists like Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas also served during the war, and the shared experience fostered a sense of camaraderie and patriotism among the artistic community.

Following the war, Mathey resumed his artistic endeavors with renewed focus. He continued to exhibit at the Salon, gradually building his reputation. He became known for his skill in portraiture, capturing not just a likeness but also the personality of his sitters. His landscapes also garnered appreciation, showcasing his ability to render atmosphere and light.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Paul Mathey's artistic style can be characterized as a form of elegant realism, marked by strong draughtsmanship, a refined sense of color, and a keen psychological insight, especially in his portraits. While he operated outside the revolutionary fervor of Impressionism, his work was not static; it demonstrated a sensitivity to contemporary life and an ability to imbue traditional genres with a fresh perspective.

His portraiture was a cornerstone of his oeuvre. Mathey possessed a remarkable ability to capture the subtle expressions and individual character of his subjects. He moved beyond mere academic likeness to explore the sitter's personality, often conveying a sense of introspection or quiet dignity. His brushwork, while controlled, could be expressive, and his handling of light and shadow was adept at modeling form and creating mood. He painted notable figures from various echelons of society, including fellow artists, musicians, and members of the aristocracy.

In addition to portraits, Mathey was a capable landscape painter. His landscape works often depicted scenes with a quiet, contemplative atmosphere. He was skilled at capturing the nuances of natural light and the textures of the environment. These works, while perhaps less central to his reputation than his portraits, demonstrate his versatility and his observational skills.

Mathey was also a highly accomplished printmaker, with a particular mastery of etching. The 19th century witnessed a significant revival of etching as an original art form, championed by artists like Charles Meryon, Félix Bracquemond, and later, James McNeill Whistler. Mathey was part of this resurgence. His etchings are characterized by their fine lines, rich tonal variations, and intricate detail. He often used printmaking to create portraits and to reproduce his own paintings or those of others, but also as a medium for original artistic expression. His technical proficiency in etching allowed him to achieve a wide range of effects, from delicate, atmospheric passages to strong, incisive lines.

His overall approach was one of thoughtful observation and meticulous execution. He did not embrace the broken brushwork or vibrant, unmixed colors of the Impressionists, nor the subjective distortions of later movements. Instead, he sought a refined naturalism, aiming for a balance between objective representation and artistic interpretation. This placed him in a category of artists who, while respecting academic tradition, were not rigidly bound by it, and who found ways to express a modern sensibility within established forms.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Paul Mathey's oeuvre, showcasing his skill in different genres and his ability to capture the essence of his subjects or scenes.

_Portrait of Edgar Degas_ (1882)

This pencil sketch, now housed in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., is a particularly insightful and intimate depiction of the renowned Impressionist master. Created when Degas was in his late forties, Mathey captures a sense of Degas's keen intellect and perhaps his famously sharp, observant personality. The drawing is rendered with a sensitivity that suggests a personal connection between the two artists. It’s a relatively informal portrayal, focusing on Degas's face and expression, highlighting Mathey's skill in draughtsmanship and his ability to convey character with economical means. The existence of such a portrait underscores Mathey's place within the Parisian art community, interacting with some of its most progressive figures.

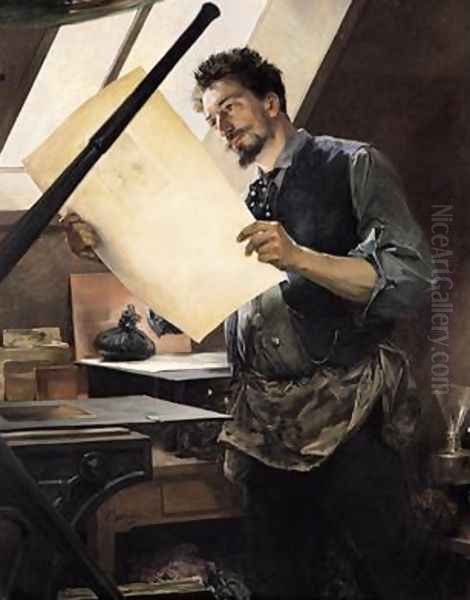

_Félicien Rops in His Studio_ (c. 1875-1900)

This painting depicts the Belgian Symbolist artist Félicien Rops (1833-1898) in his Parisian studio. Rops was known for his often provocative and macabre imagery, and Mathey’s portrayal offers a glimpse into the working environment of this distinctive artist. The composition likely includes details of Rops's studio, perhaps some of his works or tools, providing context to his artistic practice. Such a work serves not only as a portrait but also as a document of artistic life in Paris, reflecting the camaraderie and mutual interest among artists of different stylistic inclinations.

_Portrait of Loys-Henri Delteil_ (early 1890s)

Loys Delteil (1869-1927) was an important figure in the art world, known as a print collector, art historian, and the compiler of influential catalogues raisonnés of printmakers like Honoré Daumier, Jean-François Millet, and Camille Corot. Mathey's portrait of Delteil, likely an etching or a painting, would have captured a key figure in the appreciation and scholarship of graphic arts. Given Mathey's own prowess as an etcher, his connection with Delteil signifies his deep involvement in the world of printmaking, both as a creator and as part of a network of connoisseurs and scholars.

_L'élégante au miroir_ (The Elegant Woman at the Mirror, c. 1880)

This oil painting, which found its way into the collections of the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris, exemplifies Mathey's skill in genre painting and female portraiture. The theme of a woman at her toilette or before a mirror was popular in 19th-century art, explored by artists ranging from academic painters to Impressionists like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Mathey's interpretation would likely emphasize elegance, refinement, and perhaps a moment of quiet introspection. The inclusion of this work in a prestigious state collection like the Luxembourg (which focused on contemporary art) indicates the official recognition Mathey received during his lifetime.

These works, among others, highlight Mathey's versatility. He was adept at capturing the psychological depth of his sitters, documenting the artistic milieu of his time, and creating images of elegance and charm. His technical skill was consistently high across painting and printmaking, allowing him to realize his artistic intentions with clarity and precision.

Relationships with Contemporaries and the Parisian Art Scene

Paul Mathey was an active participant in the Parisian art world, and his career was interwoven with those of many prominent contemporaries. His training under established academicians placed him within a traditional lineage, yet his personal connections and artistic interests extended to more progressive circles.

His relationship with Edgar Degas (1834-1917) is particularly noteworthy. As evidenced by Mathey's portrait of Degas, and the fact that Degas himself dedicated one of his own works to Mathey, there was clearly a mutual respect and friendship. Degas, though a core figure of Impressionism, maintained a unique position, emphasizing drawing and composition, and often working from memory or sketches rather than strictly en plein air. This shared emphasis on draughtsmanship might have been a point of connection between him and Mathey.

Mathey also portrayed Georges Clairin (1843-1919), a contemporary known for his Orientalist scenes, decorative paintings, and portraits, most famously of the actress Sarah Bernhardt. Clairin, like Mathey, operated within a more academic or Salon-oriented framework, but with a flair for the dramatic and exotic. Their interaction points to the interconnectedness of artists within the mainstream Salon system.

The portrait of Félicien Rops further illustrates Mathey's engagement with artists of varied styles. Rops's Symbolist and often decadent art was quite different from Mathey's more realist approach, yet they clearly moved in overlapping circles. This suggests an openness on Mathey's part to different artistic expressions.

Mathey's social and professional life was embedded in the artistic fabric of Paris. It's noted that he lived in the same apartment building as the Taskins family, who may have been connected to the arts or music. Such proximity fostered informal networks and exchanges of ideas. He was also friends with the artist Félix Unger (1830-1912), an Austrian painter and etcher who also spent time in Paris, indicating Mathey's connections extended to international artists working in the city.

The subjects of his portraits also reveal his connections. He painted members of the French nobility, such as Philippe d'Orléans, Duke of Orléans, and prominent musicians like Camille Saint-Saëns, Gabriel Fauré, and Maurice Ravel. These commissions indicate his standing as a sought-after portraitist capable of satisfying discerning and influential clients. His ability to capture the likeness and character of such figures placed him in high regard.

While Mathey was not an Impressionist, he worked during their ascendancy. Artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley were revolutionizing landscape painting, while Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt brought Impressionist techniques to intimate domestic scenes and portraits. Mathey's adherence to a more realist style set him apart from this group, yet his friendship with Degas shows that the lines between different artistic camps were not always rigidly drawn. He would have been well aware of their innovations, even if he chose a different path.

Master Printmaker and Collector

Beyond his achievements as a painter, Paul Mathey was a distinguished printmaker, particularly excelling in the art of etching. The 19th century saw a significant revival of etching as an original art form, moving away from its primary use as a reproductive medium. Artists like Charles Meryon, with his haunting views of Paris, Félix Bracquemond, who was instrumental in popularizing Japanese influences (Japonisme) among artists, and James McNeill Whistler, whose atmospheric etchings of London and Venice were highly influential, all contributed to this "Etching Revival."

Mathey was an active participant in this movement. His etchings were praised for their technical finesse, delicate lines, and ability to capture subtle tonal gradations. He used etching for various purposes: to create original compositions, to produce portraits, and sometimes to interpret his own paintings or those of other artists in a graphic medium. His skill allowed him to convey texture, light, and psychological depth with the incisive lines of the etching needle.

His interest in printmaking was not limited to creation; Paul Mathey was also an avid collector of prints. This passion for collecting suggests a deep appreciation for the history and artistry of the medium. By exchanging works with other artists, he amassed an important collection. This practice of artists exchanging works was common and fostered a sense of community, while also allowing artists to study and be inspired by the work of their peers. His collection would have included works by contemporaries and perhaps Old Masters, reflecting his connoisseurship.

His connection with Loys-Henri Delteil, the renowned print historian and cataloguer, further underscores Mathey's immersion in the world of graphic arts. Delteil's scholarly work was crucial for the study and appreciation of printmaking, and his association with Mathey points to the artist's respected position within this specialized field.

Mathey's dedication to printmaking, both as a practitioner and a collector, highlights an important facet of his artistic identity. It demonstrates his commitment to craftsmanship and his engagement with a medium that allowed for both intimate expression and wider dissemination of images.

Later Career, Recognition, and Legacy

Paul Mathey continued to be a productive artist throughout his later career. His dedication to his craft and his consistent quality earned him significant recognition. In 1898, he was awarded the Legion of Honour (Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur), one of France's highest civilian decorations. This award signified official acknowledgment of his contributions to French art and culture, cementing his status as a respected figure in the art establishment.

His works continued to be exhibited, and he maintained a practice as a portraitist and painter. The acquisition of his painting L'élégante au miroir by the Musée du Luxembourg was a mark of distinction, as this museum was dedicated to showcasing the work of living artists deemed to be of national importance. Such acquisitions ensured that his work would be preserved for future generations and seen by a wider public.

While the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, such as Fauvism led by Henri Matisse and André Derain, and Cubism pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, began to capture public and critical attention, Mathey remained committed to his established style of elegant realism. This does not diminish his importance; rather, it highlights the diversity of artistic practice during this period. Not all artists felt compelled to join the most radical movements, and figures like Mathey continued to uphold traditions of skilled representation and psychological portraiture that retained value and appeal.

Paul Mathey passed away in 1929. His legacy lies in his body of work, which includes sensitive portraits, evocative landscapes, and masterfully executed prints. He contributed to the rich tapestry of Parisian art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period of extraordinary artistic ferment. His portraits serve as valuable documents of the personalities of his time, from celebrated artists and musicians to influential public figures.

His expertise was not solely confined to painting and printmaking. Some sources also note his interest and knowledge in architecture, particularly Roman architecture. While this aspect of his career is less documented in the context of his visual art, it suggests a broad intellectual curiosity and a Renaissance-like versatility.

Today, his works can be found in various public and private collections, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. and museums in France. While perhaps not as widely known as some of his Impressionist contemporaries, Paul Mathey remains an important artist for understanding the breadth of French art during his lifetime. He represents a strand of artistic practice that valued technical skill, refined aesthetics, and insightful observation, creating a body of work that continues to resonate with quiet power and enduring elegance. His dedication to both painting and the art of etching ensures his place among the notable French artists of his generation.