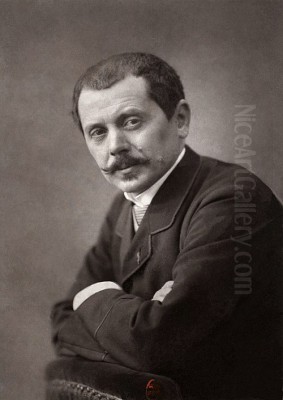

Pierre Georges Jeanniot (1848-1934) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born in Geneva, Switzerland, he possessed dual Swiss-French nationality but spent the vast majority of his prolific career in France, becoming a keen observer and skilled depictor of its multifaceted life. An accomplished painter, watercolorist, etcher, and illustrator, Jeanniot navigated the dynamic Parisian art world, leaving behind a body of work that captures both the fleeting elegance of the Belle Époque and the stark realities of military conflict. His art provides a valuable window into a transformative period in French history and culture.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born on July 2, 1848, in Geneva, Pierre Georges Jeanniot was immersed in an artistic environment from his earliest years. His father, Pierre-Alexandre Jeanniot, was an artist himself and served as the director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Dijon. This paternal influence undoubtedly shaped young Pierre Georges's path, providing him with foundational training and fostering an early appreciation for the visual arts. Under his father's tutelage, he began to develop his skills in drawing and painting, laying the groundwork for his future career.

Despite this artistic upbringing, Jeanniot initially pursued a military path, a decision that would profoundly impact his thematic concerns as an artist. This dual trajectory—military man and artist—would define much of his early professional life and provide a unique perspective that enriched his later artistic output. The discipline and observational skills honed in the military would serve him well in his meticulous depictions of both martial and civilian scenes.

A Soldier's Eye: Military Career and its Artistic Echoes

In 1866, Jeanniot made a formal commitment to a military career by entering the prestigious École Militaire de Saint-Cyr. This institution was renowned for training France's officer corps, and Jeanniot's time there would have instilled in him a deep understanding of military life, strategy, and the camaraderie of soldiers. His choice of a military career was not a brief interlude; he dedicated a significant portion of his early adulthood to service.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 proved to be a crucible for Jeanniot. Serving as an infantry officer in the 23rd Division, he experienced the brutal realities of combat firsthand. He fought bravely, was wounded in action, and his valor was recognized with the esteemed Légion d'Honneur. This direct involvement in one of the 19th century's pivotal conflicts provided him with a wealth of experiences and imagery that would later translate into powerful artistic statements. He continued his military service after the war, serving in the 94th and later the 79th divisions until 1878.

Even while serving, his artistic inclinations persisted. The experiences of war, the discipline of military routine, and the diverse characters he encountered undoubtedly fueled his desire to capture these scenes. His military background gave him an insider's perspective, allowing him to depict soldiers and battle scenes with an authenticity that artists without such experience might lack. This period was crucial in shaping his ability to convey human drama and the intensity of critical moments.

Transition to a Full-Time Artist

By 1878, health reasons prompted Jeanniot to retire from his active military career. This marked a definitive shift, allowing him to dedicate himself entirely to his passion for art. He had already begun to test the waters of the Parisian art world. In 1872, while still an officer, he made his debut at the highly influential Paris Salon, exhibiting a watercolor titled "Intérieur de forêt" (Forest Interior). The Salon was the premier venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage, and his acceptance was a significant early validation of his talent.

Upon becoming a full-time artist, Jeanniot immersed himself in the vibrant artistic milieu of Paris. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Salon, gradually building his reputation. His early works often drew upon his military experiences, but he soon broadened his thematic range, turning his keen observational skills to the bustling life of the French capital. He became a member of the Société des Artistes Français, a key institution in the French art world.

His transition was not just a change in profession but an embrace of a different way of seeing and interpreting the world. While his military life provided him with subjects of heroism and conflict, his life as a civilian artist in Paris opened up new vistas: the elegance of society, the everyday moments in cafes and streets, and the changing social landscape of the Belle Époque.

Artistic Style: Realism, Impression, and the Belle Époque

Pierre Georges Jeanniot's artistic style is characterized by a blend of academic realism, learned through his early training, and a more modern, Impressionist-influenced approach to capturing contemporary life. He was not strictly an Impressionist in the mold of Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, who focused on the optical effects of light and color, but he shared their interest in depicting modern subjects and capturing fleeting moments.

His paintings of Parisian life are particularly noteworthy. He excelled at portraying the social rituals of the Belle Époque – the fashionable gatherings in elegant salons, the promenades in the Bois de Boulogne, the lively atmosphere of theaters and cafes. In this, his work can be compared to contemporaries like Jean Béraud and James Tissot, who also specialized in chronicling the sophisticated urban society of the era. Jeanniot's figures are often rendered with a lively sense of movement and character, conveying the dynamism of the city. He had a particular talent for capturing the nuances of social interaction and the subtle details of fashion and decor that defined the period.

His military paintings, informed by his own experiences, possess a striking authenticity. Works like "La ligne de feu, retraite de la bataille de Vionville" (The Firing Line, Retreat from the Battle of Vionville, 1883) demonstrate his ability to convey the drama and chaos of battle without resorting to overly romanticized heroics. His approach was often more grounded, focusing on the human element within the larger spectacle of war. In this, he followed a tradition of French military painting established by artists like Ernest Meissonier, Édouard Detaille, and Alphonse de Neuville, but often with a more personal and less aggrandizing touch.

Jeanniot was also a skilled watercolorist, a medium that allowed for spontaneity and a fresh, luminous quality, well-suited to capturing the ephemeral aspects of modern life. His draftsmanship was strong, underpinning all his work, whether in oil, watercolor, or print.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Throughout his long career, Jeanniot produced a diverse array of works. His Salon debut piece, "Intérieur de forêt" (1872), showcased his early skill in landscape and watercolor. "Le Vernan à Nassau-Sainte-Anne" (1873) and "Fluxus" (1883) further demonstrated his developing talents.

One of his most significant military paintings is "La ligne de feu, retraite de la bataille de Vionville" (1883). This work likely drew directly from his Franco-Prussian War experiences, depicting the intensity and human cost of conflict with a realism born of observation. Such paintings contributed to his reputation as an artist capable of tackling serious historical and contemporary themes.

In his depictions of Parisian society, "Elegante au Salon" stands out. The provided information suggests two works of this or a similar title: a charcoal portrait created for Edgar Degas in 1890, and an oil painting from 1905. Both would have captured the fashionable women of the era, showcasing Jeanniot's eye for elegance and social nuance. These works place him firmly within the tradition of artists documenting the Belle Époque, a period of optimism, artistic innovation, and societal change in Paris.

Later in his career, Jeanniot also responded to contemporary events through his art. His series of etchings, "The Horrors of War," depicted atrocities committed in Belgium during the early stages of World War I. These powerful images demonstrate his continued engagement with military themes and his capacity for profound social commentary, using the stark medium of etching to convey the grim realities of modern warfare.

Master of the Line: Printmaking and Illustration

Beyond his paintings and watercolors, Pierre Georges Jeanniot was a highly accomplished printmaker, particularly skilled in etching and drypoint. His mastery of line and tone allowed him to create prints of great subtlety and expressive power. Printmaking was undergoing a revival in the late 19th century, with artists like Félix Bracquemond and Félicien Rops (though Rops's themes were often darker and more symbolist) championing it as a significant artistic medium. Jeanniot contributed to this resurgence, exploring the unique possibilities of the etched line.

His friendship with Edgar Degas, himself a master printmaker, was undoubtedly influential. They shared an interest in capturing modern life, and Degas's experimental approach to printmaking may have encouraged Jeanniot. It is known that Degas valued Jeanniot's opinion and company. Jeanniot's printmaking often mirrored the themes of his paintings: scenes of Parisian life, military subjects, and portraits.

Jeanniot was also a prolific illustrator, lending his talents to more than thirty books. He created illustrations for prominent authors of his time, including Émile Zola. Illustrating Zola's works, known for their gritty realism and social commentary, would have been a fitting task for an artist with Jeanniot's observational skills and understanding of human drama. He also reportedly illustrated works for other literary figures such as Alphonse Daudet and Guy de Maupassant, whose stories often captured the nuances of French society. His illustrations were not mere decorations but insightful visual interpretations of the texts, adding another dimension to the reader's experience.

A Network of Artists: Friendships and Influences

Pierre Georges Jeanniot was well-connected within the Parisian art world, maintaining friendships and professional relationships with some of the most influential artists of his time. His closest and perhaps most significant artistic relationship was with Edgar Degas. The two artists shared a deep mutual respect and friendship. Degas, known for his sharp wit and demanding standards, evidently valued Jeanniot's artistic judgment. An anecdote recounts Degas showing Jeanniot his sketches and, on one occasion, making a characteristically blunt remark about ballet dancers, calling them "little monkeys," which reportedly shocked Jeanniot despite the prevalent societal attitudes of the time. This interaction highlights their familiarity and Degas's often acerbic personality. Their shared interest in depicting modern life, particularly scenes of Parisian leisure and entertainment, formed a strong bond.

Jeanniot was also acquainted with Édouard Manet, another pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism. Manet's revolutionary depictions of contemporary Paris and his bold painting technique were highly influential, and Jeanniot would have been part of the circle of artists who admired and learned from his innovations.

The provided information mentions that Claude Monet, a leading figure of Impressionism, sought painting advice from Jeanniot. While Monet was a towering figure in his own right, this suggests Jeanniot was held in high esteem by his peers for his technical skill and artistic understanding.

His circle likely included other artists who depicted Parisian life, such as Jean-Louis Forain, who, like Degas, was known for his sharp observations and skills as a printmaker, and perhaps Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose depictions of Montmartre's nightlife, while stylistically different, shared a focus on contemporary urban experience. Jeanniot was also a founding member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1890, an organization established by artists like Ernest Meissonier, Auguste Rodin, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes as an alternative to the traditional Salon, indicating his standing among prominent figures. His interactions with these and other artists created a rich tapestry of mutual influence and exchange that characterized the dynamic art scene of late 19th-century Paris.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Career

Throughout his career, Pierre Georges Jeanniot actively participated in the art world through regular exhibitions. He was a consistent presence at the Paris Salon and later at the exhibitions of the Société des Artistes Français and the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. His work was not confined to Paris; he also exhibited in other French cities like Nantes and internationally, with several showings in Munich, Germany. This international exposure helped to broaden his reputation beyond France.

His participation in the 1939 New York World's Fair, even if posthumous or representing his earlier work, indicates a lasting recognition of his contribution to French art on an international stage. (It's important to note he died in 1934, so his inclusion in the 1939 fair would have been a retrospective acknowledgment).

His military service had earned him the Légion d'Honneur early in his life, a prestigious recognition of his bravery. As an artist, he continued to garner respect for his skill, his versatility, and his insightful portrayals of his era. While he may not have achieved the revolutionary fame of some of his Impressionist contemporaries, he carved out a distinguished career as a respected painter, printmaker, and illustrator.

In his later years, Jeanniot continued to work, his artistic vision shaped by decades of observation and practice. He remained a chronicler of his times, adapting his focus as the world around him changed, as evidenced by his poignant etchings of World War I.

Legacy and Conclusion

Pierre Georges Jeanniot passed away in Paris in 1934, leaving behind a substantial and varied body of work. After his death, a significant portion of his studio's contents, his "fonds d'atelier," was reportedly donated to the Georges Chaperoury Gallery, ensuring that his artistic legacy would be preserved and accessible.

Jeanniot's art offers a rich visual record of French society during a period of significant transformation. From the battlefields of the Franco-Prussian War to the elegant salons of the Belle Époque, and through the grim realities of World War I, his work reflects a keen eye for detail, a deep understanding of human nature, and a versatile command of various artistic media. He was a bridge between the academic traditions of the 19th century and the modern artistic currents that reshaped European art.

While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his avant-garde contemporaries, Pierre Georges Jeanniot remains an important figure for his authentic depictions of military life, his charming and insightful portrayals of Parisian society, and his accomplished work as a printmaker and illustrator. His art provides invaluable insights into the visual culture and social history of his time, securing his place as a dedicated and perceptive chronicler of an era. His ability to move between the grand themes of war and the intimate moments of daily life demonstrates a remarkable artistic range and a profound engagement with the world around him.