Henry Percy Gray stands as a significant figure in American art history, particularly renowned for his evocative depictions of the Northern California landscape. Active during the late 19th and first half of the 20th century (1869-1952), Gray became synonymous with atmospheric watercolor paintings that captured the unique beauty and mood of his native state. His work, deeply rooted in the Tonalist aesthetic, offers a romantic, poetic vision of California's rolling hills, majestic oaks, eucalyptus groves, and coastal vistas, securing his place as a beloved interpreter of the region's natural splendor.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in San Francisco in 1869, Percy Gray hailed from a family with considerable literary and artistic inclinations. This nurturing environment likely fostered his early interest in art. His childhood was marked by illness, which, while a personal challenge, may have encouraged introspective pursuits and sharpened his observational skills, drawing him towards artistic expression from a young age. His innate talent was evident early on.

Gray received his formal art training locally, enrolling at the San Francisco School of Design (now the San Francisco Art Institute) between 1886 and 1888. During this formative period, he studied under influential figures like Arthur Frank Mathews, a dominant force in the California Decorative Style and a proponent of Tonalism. Mathews' emphasis on harmonious color, refined composition, and atmospheric effects undoubtedly left an impression on the young artist. Gray may also have encountered other notable instructors or visiting artists associated with the school during that era, such as Emil Carlsen.

Following his studies, Gray initially pursued a career as a newspaper illustrator, a common path for artists seeking steady income at the time. He worked for the San Francisco Call, honing his skills in draftsmanship and narrative composition under the pressure of deadlines. This practical experience would serve him well, even as his aspirations shifted towards fine art painting.

New York Interlude and the Embrace of Tonalism

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Percy Gray moved to New York City around 1895. He continued his work as an illustrator, notably for the New York Journal, but more importantly, he furthered his art education. Gray enrolled at the prestigious Art Students League, a hub for aspiring artists seeking instruction from leading figures.

A pivotal influence during his New York years was William Merritt Chase. Chase, a celebrated painter and charismatic teacher, had recently returned from Europe, bringing back insights from various movements, including Impressionism and the Barbizon School. However, it was Chase's affinity for Tonalism, a style characterized by muted palettes, soft edges, and an emphasis on mood and atmosphere over precise detail, that resonated deeply with Gray. Chase, himself influenced by figures like James McNeill Whistler and the French Barbizon painters such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, imparted a sensitivity to light and shadow that Gray would adapt to his own vision.

The Tonalist movement, flourishing in America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, included prominent artists like George Inness, Dwight Tryon, and Thomas Wilmer Dewing. It offered an alternative to the brighter palette and broken brushwork of Impressionism, focusing instead on spiritual and poetic interpretations of the landscape, often depicted at twilight or in hazy conditions. Gray absorbed these principles, finding them well-suited to capturing the ethereal quality of the Northern California light and fog he remembered.

Return to California and the Shift to Watercolor

A dramatic event precipitated Gray's permanent return to his home state. In 1906, the devastating San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire ravaged the city. Gray was dispatched by the New York Journal to cover the catastrophe as an illustrator. Witnessing the destruction and the resilience of the city firsthand profoundly affected him. He decided to remain in California, leaving behind his East Coast career to dedicate himself fully to painting the landscapes he loved.

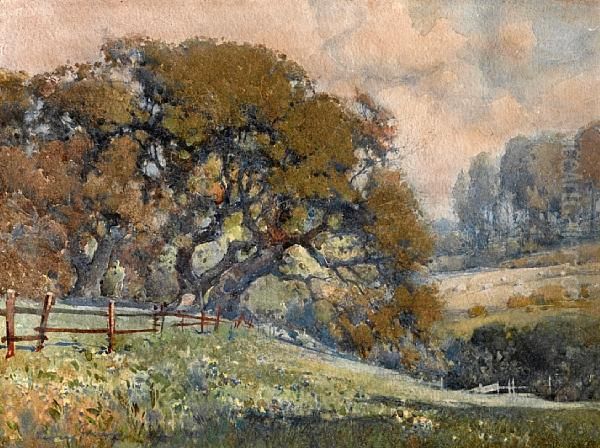

This period also marked a significant technical shift in his work. Gray developed a severe allergy to oil paints, likely due to the pigments, linseed oil, or turpentine fumes. This forced him to abandon oils and fully embrace watercolor as his primary medium. While initially a constraint, this transition proved fortuitous. Gray developed an exceptional mastery of watercolor, exploiting its transparency and fluidity to achieve the subtle atmospheric effects central to his Tonalist style. He became known for his meticulous technique within the medium, often applying washes with great control to build depth and luminosity.

His post-1906 work increasingly focused on characteristic California subjects: the rolling hills dotted with native oaks, the introduced eucalyptus groves becoming ubiquitous across the landscape, and vibrant fields of wildflowers, particularly the iconic California poppies and lupines. The 1906 earthquake experience seemed to solidify his connection to the land and its specific flora.

The Development of a Signature Style

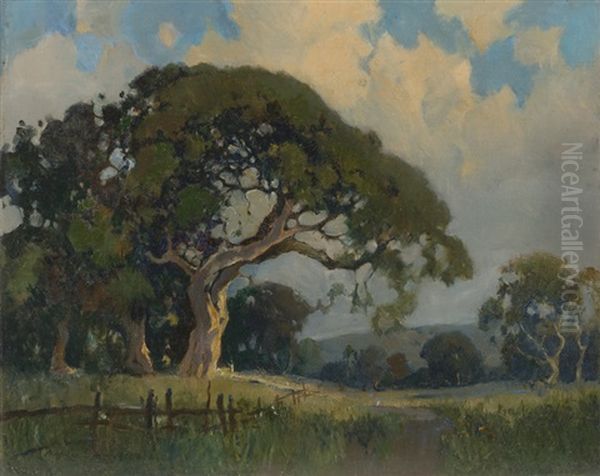

Percy Gray's mature style is a distinctive blend of Tonalist sensibility and careful observation of nature. While aware of Impressionism, and sometimes incorporating its brighter notes, particularly in his wildflower scenes, his core approach remained Tonalist. He prioritized mood, harmony, and a sense of quiet contemplation. His palette often favored soft greens, ochres, mauves, and grays, capturing the gentle, diffused light characteristic of coastal Northern California or the hazy atmosphere of its inland valleys.

Unlike the Impressionists who sought to capture a fleeting moment of light, Gray aimed for a more enduring, poetic essence. His landscapes often feel timeless and imbued with a quiet mystique. He masterfully rendered the textures of bark, the delicacy of petals, and the vastness of skies, but always subordinated detail to the overall atmospheric effect. His work invites viewers to feel the landscape as much as to see it.

Key figures of American Tonalism like Whistler and Inness provided foundational inspiration, but Gray forged his own path, applying Tonalist principles specifically to the California environment. He shared this interest with other California-based Tonalists, such as Xavier Martinez and Gottardo Piazzoni, though each developed a unique interpretation. Gray's particular focus on detailed yet atmospheric watercolors set him apart.

Subject Matter: Capturing Northern California

Percy Gray's oeuvre is a visual love letter to Northern California. He repeatedly returned to specific motifs, exploring them in varying light and weather conditions. Among his most celebrated subjects are the eucalyptus groves. Introduced from Australia, these trees had rapidly naturalized, and Gray was fascinated by their tall, slender forms, peeling bark, and the way light filtered through their leaves. Paintings titled Eucalyptus Grove or similar variations are numerous and highly sought after.

The rolling hills of Marin County, Alameda County, and the San Francisco Peninsula were another favorite theme. He captured the characteristic golden-brown of the dry season grasses and the dark, sculptural forms of Coast Live Oaks against the soft contours of the land. Mount Tamalpais, the iconic peak overlooking the San Francisco Bay, appears frequently in his work, often shrouded in mist or bathed in the warm glow of dawn or dusk. Ascending Road with Mt. Tamalpais (1910) is one example capturing this subject.

Springtime transformed these hills, and Gray excelled at depicting the explosion of wildflowers. His paintings of California poppies, lupines, and other native blooms are among his most vibrant works, showcasing his ability to handle brighter colors while retaining an overall harmony. Fields of Poppies or Lupine and Poppies represent this popular aspect of his work.

Later, especially after moving to the Monterey Peninsula, coastal scenes became more prominent. He painted the rugged coastline around Point Lobos and Carmel, capturing the dramatic interplay of Waves and Rocks (c. 1900), the distinctive forms of the Monterey Cypress trees clinging to the cliffs, and the pervasive coastal fog. Works like Point Lobos, California, 1930 exemplify this period. He also ventured into depicting the stark beauty of California's desert landscapes, capturing the unique light and flora, such as in scenes featuring Desert Verbena.

The Burlingame Years

From approximately 1912 to 1923, Percy Gray lived and maintained a studio in Burlingame, a town south of San Francisco on the Peninsula. This was a period of significant productivity and growing recognition. His proximity to the landscapes he loved allowed for frequent sketching trips and sustained focus on his painting. The eucalyptus groves and rolling hills of the Peninsula featured prominently in his work from this time.

During these years, he solidified his reputation as a leading California watercolorist. He exhibited regularly in San Francisco galleries and at venues like the Bohemian Club, an influential private club known for its artistic membership and exhibitions. His distinctive style, combining technical skill with poetic feeling, found favor with collectors and critics. Works like Country Road (c. 1915) and Cloudy Day (c. 1915) likely date from this productive era.

Recognition and Exhibitions

Percy Gray's talent did not go unnoticed in the wider art world. A significant milestone was his participation in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) held in San Francisco in 1915. This grand event, celebrating the opening of the Panama Canal and the city's recovery from the 1906 earthquake, featured a major international art exhibition. Gray's work was included, and he was awarded a Bronze Medal, a mark of distinction that significantly boosted his professional standing.

Throughout his career, Gray exhibited widely. Besides the Bohemian Club and the PPIE, his work was shown at the Del Monte Art Gallery in Monterey, an important venue for the growing Carmel and Monterey art colonies. He was also associated with the California Society of Etchers, indicating an interest in printmaking, although he is primarily known for his watercolors. His paintings were handled by prominent galleries in San Francisco and Los Angeles, ensuring his visibility within the state's burgeoning art market.

His consistent output and recognizable style made him one of the most respected landscape painters of his generation in California, alongside contemporaries working in various styles, from the Impressionism of Guy Rose and Granville Redmond to the more decorative approaches of Arthur Mathews or the robust seascapes of Armin Hansen.

Monterey and Later Life

In 1923, at the age of 54, Percy Gray married Leone Plumley. This relatively late and perhaps unexpected marriage marked a new chapter in his life. The couple subsequently moved to the Monterey Peninsula in 1924, settling into the historic Casa Bonifacio, often referred to as the "Bonito Adobe," in Monterey. This area was already a well-established art colony, attracting artists drawn to its scenic beauty and bohemian atmosphere.

Living in Monterey placed Gray in the heart of one of his favorite painting locales. His later work often focused intensely on the dramatic coastline, the ancient Monterey Cypress trees, and the atmospheric conditions of the peninsula. He became associated with the Carmel/Monterey art scene, which included artists like Armin Hansen, known for his vigorous depictions of fishermen, and Charles Rollo Peters, famed for his Tonalist nocturnes of adobe buildings. While Gray maintained his unique style, he was part of this vibrant artistic community.

He continued to paint prolifically throughout his later years, primarily focusing on watercolor landscapes. His subjects remained rooted in the California environment, from the coastal scenes near his home to occasional depictions of desert landscapes. He remained active as an artist until shortly before his death. Percy Gray passed away in San Anselmo, Marin County, in 1952, leaving behind a rich legacy of work celebrating the landscapes of his beloved state.

Watercolor Technique

Percy Gray's mastery of watercolor was central to his artistic identity. Forced into the medium by allergies, he developed a technique characterized by both precision and atmospheric subtlety. He typically worked on paper, often applying layers of transparent washes to build up color and depth, allowing the white of the paper to contribute to the luminosity of the scene.

His control was remarkable; while embracing the fluidity of watercolor, his work often displays meticulous detail, particularly in the rendering of trees, foliage, and foreground elements. This careful draftsmanship, likely honed during his years as an illustrator, provided a solid structure beneath the atmospheric washes. Some critics occasionally found his technique perhaps too controlled or "tight" for watercolor, preferring a looser handling, but for Gray, this precision was integral to capturing the specific character of the California landscape.

He was adept at suggesting fog and mist through subtle gradations of tone and soft edges. In his wildflower scenes, he demonstrated an ability to use brighter, more saturated colors effectively without sacrificing the overall harmony of the composition. He might also employ dry brush techniques to create texture, particularly for elements like tree bark or dry grasses. His technical proficiency allowed him to fully realize his Tonalist vision in a challenging medium.

Contemporaries and Context

Percy Gray's career spanned a dynamic period in California art. He emerged when the influence of the French Barbizon School and Tonalism was strong, represented locally by artists like William Keith, an earlier generation landscape painter whose work Gray would have known. Gray's training with Arthur Mathews placed him within the California Decorative Style movement, though his own work evolved more purely towards landscape Tonalism.

His time in New York exposed him to William Merritt Chase and the broader currents of American Tonalism and Impressionism. Upon returning to California, he worked alongside artists exploring various styles. While Gray remained committed to Tonalism, California Impressionism was flourishing, led by figures like Guy Rose, Granville Redmond (famous for his poppy fields, a subject Gray also favored), and E. Charlton Fortune.

In the watercolor medium, he was a contemporary of Francis McComas, another highly regarded watercolorist known for his depictions of the Monterey Peninsula and the Southwest, sometimes considered a friendly rival. Later, the Monterey Peninsula art colony thrived with artists like Armin Hansen and Charles Rollo Peters, each contributing to the region's artistic identity. Educators like Eugen Neuhaus at the University of California, Berkeley, also shaped the artistic environment. Gray navigated this diverse scene, maintaining his distinct Tonalist approach while contributing significantly to the overall tradition of California landscape painting. Sydney Yard was another notable watercolorist of the era working with similar landscape themes.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Throughout his career and posthumously, Percy Gray has generally received positive critical appraisal. He was praised for his technical skill in watercolor, his sensitive rendering of atmosphere, and his ability to capture the poetic essence of the Northern California landscape. Critics often noted the romantic charm and tranquility of his work, highlighting his role as a visual poet of the region. His paintings resonated with a public appreciative of California's natural beauty.

While highly regarded, some commentary occasionally noted a tendency towards idealization or romanticism, suggesting his landscapes sometimes presented a perfected, almost dreamlike version of reality. The meticulousness of his technique, while admired for its skill, was sometimes contrasted with the looser, more spontaneous handling favored by other watercolorists. His personal life, particularly his later marriage, might have drawn some comment in its time but has little bearing on the assessment of his artistic achievement.

Percy Gray's legacy rests on his position as one of California's foremost Tonalist painters and arguably its most accomplished watercolorist in that style during the early 20th century. He created an enduring and iconic vision of Northern California, particularly its hills, oaks, eucalyptus, and wildflowers. His work influenced subsequent generations of landscape painters in the state and continues to be highly valued for its aesthetic appeal and historical significance. He successfully translated the principles of Tonalism, often associated with East Coast landscapes, to the unique light and topography of the West.

Collections and Market

Percy Gray's paintings are held in numerous important public and private collections, attesting to his enduring significance. Major institutions with his works include the Oakland Museum of California, the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (de Young), the Laguna Art Museum, and The Irvine Museum Collection at the University of California, Irvine, among others.

Significant private holdings, such as those donated by the Cleland and Katherine Whitton family (including works like Waves and Rocks, Point Lobos, California, 1930, and portraits like Artist's Niece, Katherine Merceron Whitton) and the Dr. George Lyman and Dorothy van Sicklen family (including the commissioned Lyman Garden, 1921), highlight the personal connection many patrons felt to his work.

His paintings remain highly sought after in the art market. Auction records demonstrate consistent demand and strong prices for his watercolors. For example, Ascending Road with Mt. Tamalpais (1910) sold for $14,000 in 1995. More recently, Lyman Garden (1921) carried an estimate of $10,000-$15,000 in a 2023 auction, and Along the Edge of the Ranch (1930) was estimated at $6,000-$8,000 in 2022. These figures reflect his established reputation and the continued appreciation for his quintessential California landscapes.

Conclusion

Percy Gray dedicated his artistic life to capturing the soul of the Northern California landscape. Through his masterful command of watercolor and his deeply felt Tonalist sensibility, he created works that are both specific in their observation and universal in their appeal. From the misty heights of Mount Tamalpais to the sun-drenched fields of poppies and the wind-swept shores of Monterey, Gray's paintings offer a timeless vision of California's natural beauty. He remains a pivotal figure in American landscape painting, a technical virtuoso whose art continues to evoke the quiet majesty and poetic spirit of the West.