Benjamin Chambers Brown stands as a pivotal figure in the development of American Impressionism, particularly its vibrant expression under the unique light and landscape of California. Active during a transformative period in American art, Brown (1865-1942) dedicated his mature career to capturing the distinctive scenery of his adopted state, earning him accolades and a lasting reputation as one of the preeminent painters of the California Plein-Air movement. His canvases, often depicting the sun-drenched poppy fields and majestic mountains of Southern California, remain celebrated for their evocative beauty and technical skill.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in Marion, Arkansas, in 1865, Benjamin Brown's artistic journey began not on the West Coast but in the American South and Midwest. His initial training took place closer to home, first attending the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. He further honed his skills at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts in Missouri. During this formative period, he studied under notable instructors including Paul Harney and John Fry, who provided him with a solid grounding in academic drawing and painting techniques prevalent in the late 19th century.

Brown initially focused on portraiture and still life, traditional genres that offered potential commissions and demonstrated technical proficiency. His early work reflected the academic training he received, emphasizing careful draftsmanship and a more controlled palette. However, even in these early stages, his inherent talent was evident. His experiences in St. Louis exposed him to a growing regional art scene, but like many ambitious American artists of his generation, the lure of European art centers, particularly Paris, proved irresistible.

Parisian Studies and Impressionist Awakening

In 1890, seeking advanced training and exposure to the latest artistic currents, Brown traveled to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world at the time. He enrolled in the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school famous for attracting international students, including many Americans. There, he studied under respected academic painters such as Jean-Paul Laurens and Benjamin Constant, further refining his technical abilities within a traditional framework. The Académie Julian provided rigorous instruction, focusing on drawing from the live model and mastering composition.

While immersed in the academic environment, Brown could not escape the influence of Impressionism, which had revolutionized French painting decades earlier and whose impact was still strongly felt. The works of artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, with their emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and visible brushwork, offered a compelling alternative to staid academic conventions. His time in Paris, likely including visits to galleries and salons showcasing Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art, profoundly shaped his developing aesthetic sensibilities. He also interacted with fellow artists, including compatriot William Griffith, sharing experiences and absorbing the dynamic artistic atmosphere of the city.

Return to America and the Call of California

Brown returned to the United States after his studies in Paris, initially settling back in St. Louis and later Little Rock. He continued to work, likely still focusing on portraits and still lifes. However, the market for these genres may not have been as robust as he hoped, or perhaps a growing desire to explore landscape painting began to take hold. A significant turning point came in 1896 when he made the decisive move to Pasadena, California.

Southern California at the turn of the century was experiencing a period of growth and transformation. Its Mediterranean climate, dramatic landscapes ranging from coastal areas to mountains and deserts, and, crucially, its unique quality of light, were beginning to attract artists from across the country. Pasadena, nestled near the San Gabriel Mountains, offered picturesque scenery and a burgeoning cultural community. Brown arrived just as this regional art scene was starting to coalesce, positioning him perfectly to become one of its leading figures.

Embracing the California Landscape

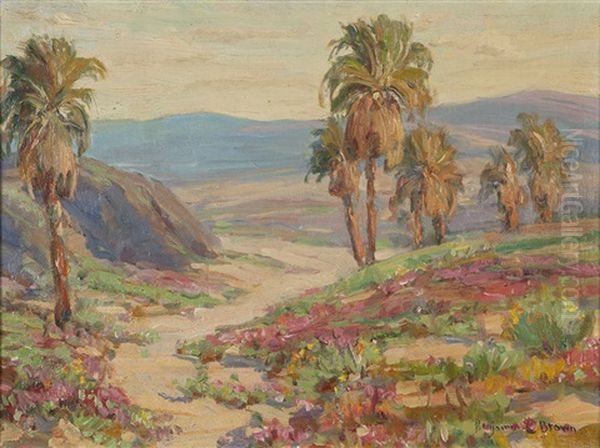

Upon settling in Pasadena, Brown's artistic focus underwent a definitive shift. Inspired by the stunning natural beauty surrounding him, he increasingly turned his attention to landscape painting. The vibrant colors, intense sunlight, and diverse terrain of Southern California provided endless subject matter. He embraced the practice of plein air painting – working outdoors directly from nature – which was central to the Impressionist ethos and particularly suited to capturing the ephemeral effects of California's light.

His dedication to outdoor work was well-known among his peers. He utilized a portable easel and paint box, often referred to as a "French kit," which allowed him the flexibility to hike into the hills or set up his easel amidst fields of wildflowers. This direct engagement with the landscape enabled him to translate the immediacy of his sensory experience onto the canvas, resulting in works characterized by freshness, spontaneity, and a palpable sense of place. This commitment earned him great respect within the growing community of Southern California artists.

California Impressionism and Brown's Style

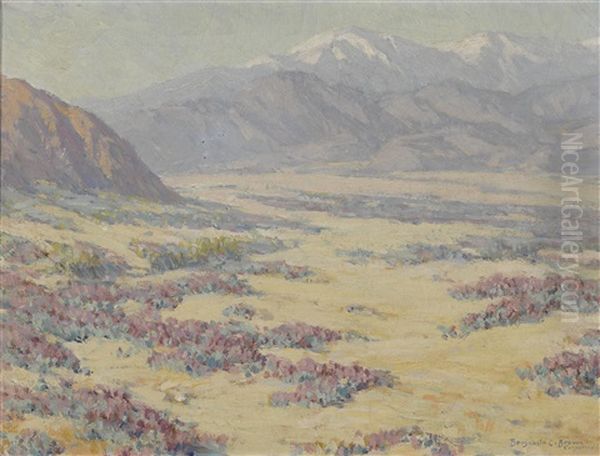

Benjamin Brown became a key proponent of what is now known as California Impressionism. While indebted to its French precursor, California Impressionism developed its own distinct characteristics, largely shaped by the region's unique environment. Artists working in this style typically employed a brighter, more vibrant color palette than their French counterparts, reflecting the intense California sunlight. Brushwork was often bold and energetic, capturing the texture and form of the landscape while emphasizing light and shadow.

Brown's style exemplifies these traits. His paintings often feature high-keyed colors, capturing the brilliance of golden poppies under a clear blue sky or the warm glow of sunlight on distant mountains. He masterfully handled the interplay of light and shadow, defining form and creating depth. While his brushwork could be loose and expressive, reflecting Impressionist technique, he often retained a strong sense of underlying structure and drawing, likely a legacy of his academic training. His compositions are typically well-balanced, conveying both the grandeur and the intimacy of the California scene. He sought to capture not just the visual appearance of the landscape, but also its mood and atmosphere.

Dean of the Pasadena Painters

Brown quickly established himself as a central figure in the Pasadena art community. His talent, dedication, and leadership qualities led to him being affectionately known as the "Dean of Pasadena Painters" and sometimes even the "Father of Pasadena Painters." He was instrumental in fostering a supportive environment for artists in the region, encouraging the development of a distinctively Californian school of landscape painting.

His contemporaries included a remarkable group of artists who collectively defined California Impressionism. Among them were figures like Guy Rose, who also studied in France and brought a refined Impressionist technique back to California; William Wendt, known for his powerful, structured landscapes; Granville Redmond, celebrated for his depictions of poppy and lupine fields, often working despite being deaf; Edgar Payne, famous for his dramatic paintings of the Sierra Nevada mountains and coastal scenes; and Franz Bischoff, renowned initially for porcelain painting but later for his bold, colorful landscapes. Other notable artists of the era included Alson S. Clark, Maurice Braun, Hanson Puthuff, and the husband-and-wife team of Elmer Wachtel and Marion Kavanagh Wachtel. Brown's work stood alongside theirs, contributing significantly to the movement's identity and success.

Signature Subjects: Poppies, Sierras, and Beyond

While Brown painted a variety of California landscapes, he became particularly renowned for two signature subjects: the rolling hills covered in California poppies and the majestic peaks of the Sierra Nevada mountains. His poppy paintings are perhaps his most iconic works. He captured the dazzling spectacle of entire hillsides ablaze with the vibrant orange state flower, often contrasting the warm hues of the poppies with the cool blues and purples of distant mountains or the bright cerulean sky. These works became emblematic of the beauty and promise of California.

His depictions of the Sierra Nevada reveal a different aspect of his artistry. These paintings often convey a sense of grandeur, solitude, and the sublime power of nature. He skillfully rendered the rugged mountain forms, the play of light on snow-capped peaks, and the deep shadows of canyons. His Sierra paintings, alongside those of artists like Edgar Payne, helped to popularize the mountain range as a subject for California artists and cemented its image in the American consciousness. Brown also traveled and painted other locations, including picturesque scenes in the San Gabriel Valley and views of the Grand Canyon in Arizona, always bringing his keen eye for light and color to the subject.

Master Etcher and Printmaker

Beyond his significant achievements in oil painting, Benjamin Brown was also a highly accomplished etcher and printmaker. He explored the expressive possibilities of line and tone offered by etching, often translating his beloved landscape subjects into the print medium. His etchings possess a similar sensitivity to light and atmosphere found in his paintings, rendered through intricate linework and careful tonal gradations.

Recognizing the importance of printmaking as an art form, Brown, along with his brother Howell C. Brown, took a leading role in establishing a formal organization for printmakers in the region. In 1914, they co-founded the Print Makers Society of Los Angeles. This organization, later renamed the California Society of Printmakers, played a crucial role in promoting printmaking on the West Coast, organizing exhibitions, and supporting artists working in various print media. Their efforts helped elevate the status of printmaking and provided a vital platform for artists exploring etching, lithography, and woodblock printing. Brown's involvement underscores his commitment to the broader artistic community and his versatility across different mediums.

Recognition and Exhibitions

Brown's talent did not go unrecognized during his lifetime. He began successfully marketing his landscape paintings in the early 20th century, finding an eager audience among collectors and tourists captivated by his depictions of the California dream. He exhibited widely, both regionally and nationally, contributing to the growing reputation of California art.

His work was featured in major expositions, which were significant platforms for artists to gain visibility. He showed work at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle in 1909 and, notably, at the prestigious Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) held in San Francisco in 1915. The PPIE was a landmark event for California artists, showcasing their work to an international audience. Brown also received several prestigious awards for his art. He won a bronze medal at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon, in 1905. At the Panama-California Exposition held in San Diego in 1915, he achieved even greater success, winning both a silver and a gold medal, solidifying his standing as one of the state's leading painters.

Representative Works and Legacy

While many specific titles exist, Brown's oeuvre is often characterized by recurring themes. Works titled California Poppies, The Poppy Field, Sierra Peaks, Sunlit Hills, or Eucalyptus Grove are typical of his output. One specifically mentioned work, The Joyous Garden, Pasadena (circa 1910), likely encapsulates his mature style: a vibrant depiction of a cultivated or semi-wild landscape near his home, rendered with bright colors, attention to sunlight effects, and expressive brushwork, celebrating the beauty of the local environment. His paintings consistently convey a deep appreciation for the natural world, rendered with both technical skill and emotional resonance.

Benjamin Chambers Brown's health began to decline in the 1920s, but he continued to work as much as his condition allowed. He passed away in Pasadena on January 19, 1942, leaving behind a significant body of work and an enduring legacy. He was a foundational figure in the California Impressionist movement, helping to define its aesthetic and contributing to its national recognition. His paintings captured the unique essence of the California landscape at a time when the state was forging its identity, and his work continues to resonate with viewers today.

His influence extended beyond his own canvases; through his leadership, his co-founding of the Print Makers Society, and his role as a respected elder statesman in the Pasadena art community, he helped shape the course of art in Southern California. His works are held in numerous important collections, including the Pasadena Museum of History, the Irvine Museum Collection at the University of California, Irvine, the Laguna Art Museum, the Oakland Museum of California, and many private collections, ensuring that his vision of California's golden landscapes continues to be appreciated. Benjamin Chambers Brown remains a celebrated master of American Impressionism, forever associated with the light, color, and beauty of his adopted state.