Philippe Mercier stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 18th-century British art. A painter and etcher of considerable talent and adaptability, Mercier played a crucial role in introducing and popularising the lighthearted elegance of the French Rococo style to a British audience. Born in Berlin to French Huguenot parents, his career unfolded primarily in England, where he navigated the worlds of royal patronage, provincial gentry, and the burgeoning London art market. His work, particularly in the genres of the conversation piece and the 'fancy picture', left a distinct mark on the artistic tastes of the era and influenced a generation of native-born artists. Understanding Mercier requires exploring his unique background, his stylistic innovations, his connections to contemporaries, and the fluctuating fortunes of his professional life.

Origins and Artistic Formation

Philippe Mercier entered the world in Berlin, the capital of Brandenburg-Prussia, likely in 1689, though some sources suggest 1691. His family background was pivotal; they were Huguenots, French Protestants who had fled persecution in their homeland following Louis XIV's revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Berlin, under the welcoming policy of Frederick William, the Great Elector, became a major refuge for these skilled artisans and professionals. Mercier's father was reportedly a tapestry weaver, embedding the young Philippe in a milieu where craftsmanship and design were valued.

This Huguenot network often facilitated education and professional opportunities. Mercier received his formal artistic training at the Berlin Academy of Arts (Akademie der Künste). His principal teacher was Antoine Pesne (1683-1757), a highly regarded French painter who had himself settled in Berlin and become court painter to the Prussian kings. Pesne, a master of the late Baroque and emerging Rococo styles, would have imparted a sophisticated, Continental approach to portraiture and decorative painting. It is likely that Pesne's own success at court provided a model for Mercier's later ambitions.

Following his studies in Berlin, Mercier is believed to have travelled, possibly spending time in France and Italy to further hone his skills and absorb different artistic currents, although details of these journeys remain somewhat obscure. Exposure to the latest Parisian fashions, particularly the work of artists like Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), whose influence would become profoundly important for Mercier, was almost certain. This period of travel and study equipped him with a versatile technique and an understanding of the prevailing European tastes.

Arrival and Ascent in England

Around 1716, Mercier made the decisive move to London. This was a period of significant cultural exchange, following the Hanoverian succession in 1714 which brought George I to the British throne. London was a magnet for talent from across Europe, and Mercier, with his Continental training and fashionable style, was well-positioned to make his mark. The exact circumstances of his arrival are unclear, but he likely leveraged connections within the Huguenot community or sought opportunities linked to the new Hanoverian court.

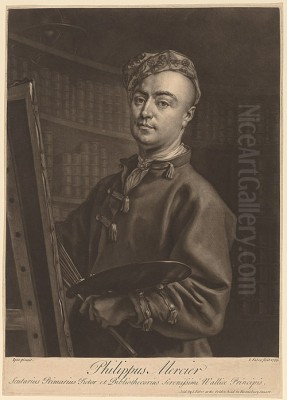

His talent did not go unnoticed for long. A pivotal moment came with his introduction to the household of Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707-1751), the son of King George II and Queen Caroline. Frederick, known for his interest in the arts and his often strained relationship with his parents, established his own court and became a significant patron. Mercier found favour with the Prince and, by the late 1720s (around 1729), was appointed as his Principal Painter and Librarian. This prestigious position provided not only a regular income but also invaluable access to aristocratic circles.

During this period, Mercier was commissioned to paint numerous portraits of Prince Frederick, his wife Princess Augusta, and their sisters. These works often displayed a charm and relative informality that aligned with the developing Rococo aesthetic, moving away from the stiffer, more imposing Baroque portraiture associated with artists like Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723), who had dominated the previous generation. Mercier's royal connection cemented his reputation as a fashionable artist in London.

Master of the Conversation Piece

One of Mercier's most significant contributions to British art was his mastery of the "conversation piece." This genre, which gained enormous popularity in 18th-century Britain, depicted small, informal groups, typically families or friends, engaged in genteel activities within a domestic or garden setting. It represented a shift towards a more intimate and naturalistic portrayal of social life, reflecting the values of the landed gentry and prosperous middle classes.

Mercier was among the earliest and most adept practitioners of this genre in England. His conversation pieces combined the elegance learned from French models, particularly Watteau, with a sensitivity to character and setting that appealed to British tastes. He skillfully arranged figures in relaxed, interactive poses, suggesting narratives or capturing specific moments in time. The settings were often detailed, showcasing the patrons' homes, gardens, and possessions, adding an element of social documentation.

Works like The Schutz Family (c. 1725) or depictions of musical parties exemplify his approach. Figures are rendered with a delicate touch, their clothing and features carefully observed, yet integrated into a harmonious composition. These paintings offered patrons a more personal and engaging form of portraiture than the grand, formal styles. Mercier's success in this area helped establish the conversation piece as a major genre, paving the way for later artists like Arthur Devis (1712-1787) and, to some extent, the early work of Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788).

Fancy Pictures and Genre Scenes

Alongside portraiture and conversation pieces, Mercier excelled in creating "fancy pictures." These were idealized genre scenes, often featuring children, rustic figures, or allegorical themes, rendered with a charming, sometimes sentimental, touch. Unlike conversation pieces, which depicted specific individuals, fancy pictures focused on more generic types and situations, allowing for greater artistic invention and emotional expression.

His most famous works in this vein form a series depicting The Five Senses (c. 1744-1747). Each painting typically features one or two figures demonstrating sight, hearing, smell, taste, or touch through specific actions and objects. For example, Taste might show a figure savouring fruit, while Hearing could depict someone listening intently to music. These works combined Rococo grace with influences from 17th-century Dutch genre painters, showcasing Mercier's ability to synthesize different traditions. The series proved highly popular and exists in several versions, now housed in major collections like the Yale Center for British Art and Tate Britain.

Mercier also engaged with literary subjects. He produced a series of twelve etchings illustrating Samuel Richardson's immensely popular novel Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded. These prints, while perhaps less artistically refined than his paintings, demonstrate his versatility and engagement with contemporary culture. His fancy pictures and genre scenes catered to a growing market for decorative and emotionally appealing art, distinct from formal portraiture or grand history painting. They often carried subtle moral or sentimental messages, resonating with the sensibilities of the time.

Portraiture: Elegance and Naturalism

While renowned for his group portraits and genre scenes, Mercier remained an accomplished painter of single portraits throughout his career. His approach here also reflected the Rococo preference for elegance, charm, and a degree of psychological insight. He moved beyond the often formulaic conventions of earlier British portraiture, seeking a more relaxed and natural presentation of his sitters.

His royal portraits, such as those of Prince Frederick and his family, showcase this style. Even within the constraints of official commissions, Mercier often managed to inject a sense of personality and approachability. His handling of fabrics – silks, satins, lace – was typically adept, capturing the textures and sheen favoured in Rococo fashion, yet without overwhelming the sitter's likeness.

Beyond the court, Mercier painted members of the aristocracy and gentry. These portraits often adopted slightly more informal poses and settings compared to state portraiture. He was skilled at capturing a pleasing likeness, flattering his subjects while retaining a sense of individuality. His palette tended towards lighter, brighter colours than the preceding Baroque era, contributing to the overall sense of grace and refinement. His style offered an appealing alternative to the more robust, sometimes satirical, realism of a contemporary like William Hogarth (1697-1764) or the straightforward competence of rivals like Thomas Hudson (1701-1779).

The Influence of Watteau

The art of Antoine Watteau cast a long shadow over the early 18th century, and Mercier was one of the primary channels through which Watteau's influence reached Britain. Mercier deeply admired the French master's fêtes galantes – idyllic scenes of aristocratic figures enjoying leisure and courtship in parkland settings – as well as his drawings and studies of character types.

Mercier absorbed Watteau's lightness of touch, his delicate colour harmonies, and his interest in depicting nuanced social interactions and fleeting emotional states. This is evident not only in Mercier's conversation pieces, which echo the group dynamics of the fêtes galantes, but also in some of his fancy pictures. He adopted themes of music, masquerade, and quiet contemplation that were hallmarks of Watteau's oeuvre.

Furthermore, Mercier played a crucial role in disseminating Watteau's designs through printmaking. He produced numerous etchings based on Watteau's paintings and drawings, making these fashionable French images accessible to a wider British audience of collectors and artists. While some critics then and now have found Mercier's handling occasionally coarser or less ethereal than Watteau's, his role in popularizing the 'Watteauesque' style in Britain is undeniable. He adapted French Rococo elegance for a British market that was receptive but also developing its own distinct artistic identity. This connection places him alongside other Rococo masters like François Boucher (1703-1770) and Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806) in the broader European movement, though his career path was unique.

Patronage, Scandal, and Provincial Life

Mercier's period as Principal Painter to the Prince of Wales marked the apex of his courtly success. However, his relationship with Prince Frederick proved volatile. Around 1736 or 1737, Mercier lost his position and fell out of favour. The precise reasons remain murky, often vaguely described as involvement in a "scandal." This could have related to court politics, financial dealings, or personal conduct – the Prince's household was known for its intrigues and factions. Whatever the cause, the loss of royal patronage was a significant blow, depriving him of a key source of income and prestige.

Following this setback, Mercier left London around 1739 and settled in York, a major social and cultural centre for the North of England. This move proved astute. He found a new and appreciative clientele among the wealthy gentry and merchants of Yorkshire and surrounding counties. For over a decade, he maintained a successful practice in the North, painting portraits, conversation pieces, and fancy pictures for families like the Ingilbys of Ripley Castle. This period demonstrates his resilience and ability to adapt to changing circumstances, finding success outside the competitive hothouse of the London art world.

His time in York allowed him to continue developing his style, perhaps with slightly more freedom than under direct court scrutiny. The portraits from this era often maintain his characteristic elegance but can sometimes exhibit a straightforwardness suited to his provincial patrons. He remained a significant artistic presence in the North until his eventual return to London.

The London Art Scene: Contemporaries and Competition

Throughout his career, Mercier operated within a dynamic and increasingly competitive art market. In London, he rubbed shoulders with, and competed against, a diverse range of artists. William Hogarth was a towering figure, though his focus on satirical narrative series and robust realism differed greatly from Mercier's Rococo charm. Thomas Hudson emerged as a leading portrait painter, known for his solid, reliable likenesses, becoming a direct competitor for commissions, particularly after Mercier's departure from court favour.

Other notable contemporaries included Joseph Highmore (1692-1780), who also painted conversation pieces and, like Mercier, illustrated Richardson's Pamela. Arthur Devis specialized almost exclusively in conversation pieces, though often with a stiffer, more doll-like quality than Mercier's work. The Scottish painter Allan Ramsay (1713-1784) was another rising star in portraiture, eventually gaining royal favour himself, known for his sensitive and refined depictions.

Mercier's Continental background and style set him apart, offering patrons a distinctly French flavour. However, he also had to contend with the growing confidence and ambition of native British artists. His career reflects the complex interplay of imported styles and local tastes that characterized the Georgian art world. He also worked during a time when artists from other parts of Europe found success in London, such as the Venetian pastel portraitist Rosalba Carriera (1675-1757), whose visits influenced taste, or fellow Frenchmen working in decorative arts or specialized genres like Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755), known for animal painting.

Later Years and Legacy

Mercier returned to London around 1751, spending the last decade of his life there. While he continued to paint, he perhaps never fully regained the prominence he had enjoyed during his association with the Prince of Wales. The artistic landscape was also changing, with the generation of Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) beginning to emerge, heralding a shift towards new styles and the eventual establishment of the Royal Academy of Arts (founded in 1768, after Mercier's death).

He died in London on July 18, 1760. His daughter, Charlotte Mercier (c. 1738-1762), followed him into the arts, known primarily for her portraits and miniatures, though contemporary accounts sometimes described her lifestyle as unconventional or 'dissolute'. Philippe Mercier's own reputation fluctuated after his death. While recognized for his skill and charm, he was sometimes overshadowed by Watteau, on the one hand, and the major figures of the later British school, on the other.

However, art historical assessment increasingly recognizes Mercier's crucial role. He was instrumental in transplanting the Rococo aesthetic to Britain, adapting its elegance and intimacy for a new audience. His popularization of the conversation piece had a lasting impact on British portraiture. His fancy pictures contributed to the development of genre painting. He stands as a key transitional figure, bridging Continental styles and the burgeoning British school, enriching the nation's artistic culture through his unique Huguenot heritage and versatile talents. His work continues to be appreciated for its charm, technical skill, and its window onto the social life of Georgian England.

Conclusion

Philippe Mercier's career is a fascinating study in artistic adaptation and cultural exchange. From his Huguenot roots in Berlin and training under Antoine Pesne, he brought a sophisticated Continental style to Hanoverian London. Finding favour, and then disfavour, at the court of Frederick, Prince of Wales, he demonstrated resilience by building a successful practice in York before returning to the capital. As a pioneer of the Rococo in Britain, a master of the conversation piece, and a creator of appealing fancy pictures like The Five Senses, he significantly shaped the tastes of his time. Though perhaps not as revolutionary as Hogarth or as foundational to the later British school as Reynolds or Gainsborough, Mercier's influence was pervasive. He skillfully blended French elegance with British sensibilities, leaving behind a body of work that remains engaging and historically important, reflecting the complex and vibrant art world of the 18th century.