Pierre-Alexandre Wille, a notable figure in the Parisian art scene of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, carved a niche for himself as a painter and engraver. Born into an artistic family, his career navigated the shifting tides of artistic taste, from the lingering influence of Rococo sentimentality to the burgeoning ideals of Neoclassicism and the dramatic societal upheavals of the French Revolution. While perhaps not as globally renowned today as some of his contemporaries, Wille's contributions to genre painting, his meticulous technique, and his engagement with the artistic life of his time warrant closer examination.

Early Life and Artistic Lineage

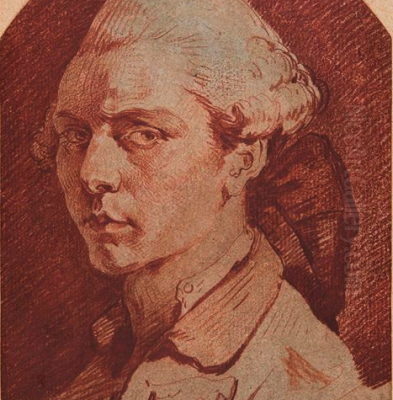

Pierre-Alexandre Wille was born in Paris on July 19, 1748. His artistic path was, in many ways, predestined. He was the son of Johann Georg Wille (also known as Jean-Georges Wille), a highly respected German engraver who had established a prominent and influential studio in Paris. The elder Wille was celebrated for his technical brilliance and his reproductive engravings after Old Masters and contemporary painters, making his workshop a hub for artists and connoisseurs. This environment undoubtedly provided Pierre-Alexandre with his earliest exposure to art, immersing him in discussions of technique, composition, and the works of diverse European schools.

His father's guidance was foundational, providing him with the rudiments of drawing and an appreciation for precision, a quality that would later manifest in his own detailed paintings. The elder Wille's connections within the Parisian art world also meant that young Pierre-Alexandre had access to a network of established artists and potential mentors from a very early age.

Formal Training and Key Influences

To further his formal artistic education, Pierre-Alexandre was placed under the tutelage of some of the most significant painters of the era. From 1761 to 1763, he studied with Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Greuze was immensely popular for his sentimental and moralizing genre scenes, which resonated deeply with the Enlightenment-era public's appreciation for virtue, domesticity, and emotional expression. Works like Greuze's The Village Bride (1761) or The Father's Curse (1777) captivated audiences with their dramatic narratives and focus on familial relationships. Wille absorbed much from Greuze, particularly the interest in everyday subjects, the emphasis on legible storytelling, and a certain tender, sometimes sentimental, approach to his figures.

Following his time with Greuze, Wille sought further instruction from Joseph-Marie Vien. Vien was a pivotal figure in the transition towards Neoclassicism in France, advocating for a return to the clarity, simplicity, and moral seriousness of classical art. He was also the teacher of Jacques-Louis David, who would become the leading exponent of the Neoclassical style. Wille's period with Vien, though reportedly brief (around 1767), exposed him to this emerging aesthetic. While Wille's primary artistic allegiance would remain closer to Greuze's genre style, the contact with Vien's Neoclassical principles likely broadened his artistic vocabulary and understanding of contemporary trends. Ultimately, however, he found himself drawn back to the stylistic orbit of Greuze, becoming one of his more notable followers.

Other prominent artists of the period whose work would have formed the backdrop to Wille's development include the Rococo master Jean-Honoré Fragonard, known for his exuberant and sensuous paintings like The Swing; the still-life and genre painter Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, whose quiet domestic scenes were admired for their sincerity and masterful technique; and portraitists like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who captured the elegance of the Ancien Régime's elite. The artistic landscape was rich and varied, offering a multitude of influences.

Academic Recognition and Artistic Style

Pierre-Alexandre Wille's talent gained official recognition when, in 1774, he was "agréé" (approved) by the prestigious Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris. He was admitted as a "peintre de sujets familiers," a painter of familiar or genre subjects. This designation acknowledged his specialization in scenes of everyday life, a field in which his master Greuze had excelled. While becoming "agréé" was a significant step, allowing him to exhibit at the official Salons, he apparently never achieved the status of a full Academician.

Wille's artistic style is characterized by its realism, particularly in the depiction of domestic interiors and family life. He inherited Greuze's penchant for narrative and sentiment, often portraying tender moments, acts of charity, or scenes imbued with a gentle moral lesson. A distinctive feature of his work, and one that garnered considerable public appreciation, was his meticulous rendering of textiles. The sheen of silk, the texture of wool, or the crispness of linen were depicted with a loving attention to detail that perhaps reflected the engraver's precision inherited from his father. This skill in capturing surfaces set his work apart and appealed to a public that valued technical finesse.

His palette was generally harmonious, and his compositions, while often drawing on established genre conventions, were carefully constructed. He was less overtly dramatic or moralizing than Greuze, often favoring a quieter, more intimate mood. His figures, while expressive, tended towards a softer, less theatrical sentimentality.

Representative Works

Among Pierre-Alexandre Wille's known works, a few stand out as representative of his skills and thematic concerns. An early engraving, Apollo Drawing his Bow (1763), demonstrates his proficiency in this medium, likely honed under his father's direct supervision. This work, with its classical subject, might also reflect an early engagement with academic themes or perhaps the influence of Vien's Neoclassical leanings.

More typical of his mature output as a painter is Alms Giving (or Charity), an oil painting from 1777. This work exemplifies his focus on "sujets familiers" and themes of virtue. Such paintings depicted acts of kindness and compassion, resonating with the Enlightenment's emphasis on sensibility and social responsibility. These scenes allowed Wille to showcase his skill in portraying human emotion and, importantly, his mastery in rendering varied textures of clothing and domestic settings.

His oeuvre largely consisted of these genre scenes, often featuring mothers and children, domestic tasks, or moments of quiet reflection. While specific titles of numerous works may not be widely circulated today, the general character of his production is consistent with his academic designation and the prevailing tastes for sentimental genre painting. He also produced portraits, though he is less known for these compared to specialists like François Gérard or Adélaïde Labille-Guiard.

The Artist as Collector and Diarist

Beyond his activities as a painter and engraver, Pierre-Alexandre Wille was also an avid art collector and a dedicated diarist. His collection was notably diverse, encompassing works by French, Dutch, and German artists. This interest in collecting demonstrates a broad appreciation for art history and different national schools. The Dutch Golden Age painters, such as Gerard ter Borch or Gabriel Metsu, with their refined interior scenes and exquisite rendering of fabrics, likely held a particular appeal for an artist like Wille, whose own work shared some of these preoccupations. He is also known to have made engravings after some of the works in his collection, a practice common among artist-collectors of the time, serving both to disseminate images of these works and to provide an additional source of income. In 1784, a significant portion of his collection, numbering around 400 pieces, was sold, an event that, while financially successful, reportedly caused him some emotional distress due to his attachment to the artworks.

Wille's diaries offer invaluable insights into his life, his thoughts on art, his travels, and the daily goings-on of the Parisian art world. These personal writings, now dispersed and preserved in institutions such as the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, provide a first-hand account of an artist's life during a transformative period in French history. Such documents are precious for art historians, offering details and perspectives often absent from official records. They reveal his interactions with other artists, his opinions on exhibitions, and the personal and professional challenges he faced.

Navigating the French Revolution

The French Revolution, beginning in 1789, profoundly impacted all aspects of French society, including the lives of artists. Pierre-Alexandre Wille, like many of his contemporaries, was caught up in these tumultuous events. He is recorded as having joined the National Guard, a citizen's militia formed during the Revolution. His service, however, was reportedly curtailed due to financial difficulties, a common plight as traditional systems of patronage and the art market were disrupted by the political and social upheaval.

There is also a mention of him serving as a commander of the Cordeliers brotherhood. The Cordeliers Club was one of the more radical political groups during the Revolution, with prominent members like Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins. If Wille held a position of command within a group associated with the Cordeliers, it would suggest a degree of active political engagement, though the precise nature and extent of this role remain somewhat obscure in the available information. The Revolution saw artists like Jacques-Louis David rise to prominence through their political activism and art that served the new republic, while others struggled to adapt or found their careers irrevocably altered.

Later Years, Declining Fame, and Legacy

The artistic landscape continued to shift in the post-Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras. The sentimental genre scenes that had been popular in the mid-to-late 18th century gradually fell out of favor, supplanted by the heroic Neoclassicism of David and his school, and later by the emerging Romantic movement with artists like Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze himself had stopped exhibiting at the Salon after a dispute with the Academy in 1769, and his influence, though still felt, began to wane over time. As a follower of Greuze, Pierre-Alexandre Wille's reputation also experienced a gradual decline. While his works likely continued to find a market among certain collectors, he did not achieve the lasting fame of some of his more innovative or politically aligned contemporaries.

He exhibited at the Salon for the last time in 1819, after which he seems to have faded from public view. His final years were reportedly marked by health problems. Pierre-Alexandre Wille passed away in 1837, at the age of 69, according to the information provided, though some art historical sources cite an earlier death date of 1821. Such discrepancies are not uncommon for artists of this period where record-keeping could be inconsistent.

His personal life included his marriage to Claude-Paule Allais (or Abaou) between 1775 and 1782. They had a son who reportedly also pursued an artistic career, continuing the family's engagement with the arts into another generation.

Wille in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Pierre-Alexandre Wille's position, it is useful to consider him alongside other artists active during his lifetime. His father, Johann Georg Wille, was a contemporary of engravers like Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger, who was also an influential writer and administrator in the arts. Wille's teacher, Greuze, stood somewhat apart from the dominant Rococo frivolity of artists like François Boucher (who died in 1770, but whose influence lingered) and Fragonard, offering a more moralizing and sentimental vision.

Wille's other teacher, Vien, paved the way for the Neoclassical revolution led by his student David. David's powerful, politically charged works like The Oath of the Horatii (1784) or The Death of Marat (1793) came to define the art of the Revolutionary period. Other artists navigating this era included Hubert Robert, known for his picturesque paintings of ruins, and Claude-Joseph Vernet, celebrated for his seascapes and landscapes.

In the realm of sculpture, contemporaries included Jean-Baptiste Pigalle and Étienne Maurice Falconet, whose styles evolved from Rococo grace to a more Neoclassical sensibility. Wille's focus on genre painting placed him in a different sphere, one that valued intimate observation and relatable human experience over grand historical or mythological narratives. He shared this focus with other, perhaps lesser-known, "petits maîtres" who catered to a bourgeois clientele.

Conclusion

Pierre-Alexandre Wille represents an interesting facet of 18th and early 19th-century French art. Born into an artistic dynasty and trained by prominent masters, he successfully navigated the Parisian art world for several decades. His specialization in genre scenes, characterized by meticulous detail, particularly in the rendering of textiles, and a gentle sentimentality, found favor with the public of his time. While his fame may have been eclipsed by artists who more dramatically shaped the major stylistic shifts of the era, his work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of everyday subjects and skilled craftsmanship.

His activities as a collector and diarist further enrich our understanding of him as an individual deeply immersed in the artistic culture of his period. The challenges he faced during the French Revolution reflect the broader societal disruptions that impacted countless lives. Though his star faded in his later years, Pierre-Alexandre Wille's paintings and engravings offer a valuable window into the tastes, values, and artistic practices of a vibrant and transformative period in French art history. His legacy lies in his contribution to the tradition of genre painting and in the personal records that help illuminate the world in which he lived and worked.