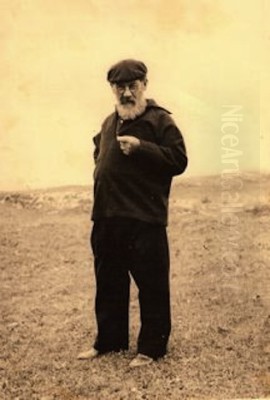

Pierre Gaston Rigaud, a name perhaps less universally recognized than some of his contemporaries, nonetheless carved a distinct and significant niche for himself within the vibrant tapestry of French art at the turn of the 20th century. Born in the historic city of Bordeaux in 1874 and passing away in 1939, Rigaud's life and career spanned a period of immense artistic ferment and innovation. He is primarily celebrated for his evocative depictions of cathedral interiors and his sensitive renderings of landscapes, works that reveal a profound engagement with the principles of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. His ability to capture the ethereal play of light within grand architectural spaces earned him the informal title of "painter of cathedrals," a testament to his dedication to this challenging and inspiring subject matter.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Bordeaux and Paris

Pierre Gaston Rigaud's artistic journey began in Bordeaux, a city with a rich cultural heritage and a burgeoning arts scene. It was here that he received his foundational artistic education, immersing himself in the techniques and traditions that would underpin his later explorations. The specific details of his early tutors or the precise curriculum he followed are not extensively documented, but it is clear that this initial training provided him with the technical proficiency necessary to pursue a career as a painter. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Rigaud recognized that Paris was the undeniable epicenter of the art world, a crucible where new ideas were forged and reputations were made.

Drawn by the allure of the capital, Rigaud made the pivotal move to Paris to further his studies and immerse himself in its dynamic artistic environment. The Paris he encountered was a city alive with debate and experimentation. The Impressionist revolution, though its first major exhibition was decades past, continued to cast a long shadow, its principles having irrevocably altered the course of Western art. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley had championed painting en plein air, capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere with broken brushwork and a vibrant palette. Their legacy was being built upon and challenged by a new wave of artists, the Post-Impressionists, who, while indebted to Impressionism, sought new avenues for personal expression and formal structure.

The Embrace of Light: Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Currents

Pierre Gaston Rigaud's artistic development was profoundly shaped by these prevailing currents. He absorbed the Impressionists' fascination with light and its transient effects, a concern that would become central to his oeuvre, particularly in his celebrated cathedral interiors. The way light filtered through stained glass, illuminated ancient stonework, and created shifting patterns of color and shadow became a recurring motif in his work. He understood that light was not merely an illuminator but an active agent, capable of transforming a space and evoking a powerful emotional response.

However, Rigaud's work also suggests an engagement with Post-Impressionist sensibilities. While Impressionism often prioritized the optical sensation, Post-Impressionism encompassed a broader range of approaches, from the structural concerns of Paul Cézanne to the expressive color of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, and the scientific pointillism of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Rigaud’s paintings, particularly his cathedral scenes, often exhibit a strong sense of structure and composition that goes beyond the purely ephemeral. There is a solidity to his architectural forms, even as they are bathed in atmospheric light, suggesting a desire to balance observed reality with a more considered, almost timeless, depiction of these sacred spaces. His landscapes, too, while capturing the immediacy of a moment, often possess a thoughtful arrangement of forms and a nuanced understanding of color harmonies.

Masterpieces of Light and Stone: Key Works

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be elusive, several key works by Pierre Gaston Rigaud stand out, illustrating his distinct artistic vision and technical skill. Among these, Cathédrale Saint-André, painted in 1912, is particularly noteworthy. Likely depicting the grand Gothic cathedral of his native Bordeaux, this work would have offered Rigaud a familiar yet endlessly fascinating subject. One can imagine him exploring the vast nave, the soaring vaults, and the intricate details of the choir, all animated by the interplay of light streaming through its historic windows. His focus would have been on capturing not just the architectural facts, but the spiritual ambiance and the almost palpable sense of history contained within its walls.

Another significant piece, Vue du bassin d'Arcachon from 1913, demonstrates his capabilities as a landscape painter. The Arcachon Bay, a vast inlet on the Atlantic coast near Bordeaux, is renowned for its unique light and picturesque scenery, from oyster beds to pine forests and elegant villas. Rigaud's painting likely captured the shimmering quality of the water, the distinctive silhouettes of the local fishing boats (pinasses), and the expansive sky, all rendered with an Impressionistic sensitivity to atmospheric conditions. This work would have allowed him to explore the effects of natural light in an open-air setting, a contrast to the more contained, filtered light of his cathedral interiors.

A later work, Chartres Cathedral at Three O’Clock, dated 1922, further underscores his dedication to ecclesiastical subjects and his meticulous observation of light. The specificity of the time in the title suggests a deliberate study of how the light at that particular hour interacted with the magnificent Gothic architecture of Chartres, famed for its unparalleled 12th and 13th-century stained glass. Rigaud would have been captivated by the deep blues, rich reds, and jewel-like tones cast by the windows, transforming the stone interior into a kaleidoscope of color. His challenge would have been to translate this complex visual experience onto canvas, conveying both the grandeur of the space and the ephemeral beauty of the light.

These works, and others like them, reveal Rigaud's consistent preoccupation with light as a primary subject. He was less concerned with narrative or overt symbolism than with the visual poetry created by light interacting with form, whether the man-made splendor of a cathedral or the natural beauty of a coastal landscape.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and the Parisian Art Scene

Pierre Gaston Rigaud was an active participant in the Parisian art world, exhibiting his work in prominent venues that showcased both established and emerging talent. His participation in the Salon des Indépendants is particularly significant. Founded in 1884 by artists such as Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Albert Dubois-Pillet, the Salon des Indépendants operated under the motto "sans jury ni récompense" (without jury nor reward), providing an open platform for artists to exhibit works that might be rejected by the more conservative official Salon. Exhibiting here placed Rigaud among the avant-garde and demonstrated his alignment with more progressive artistic tendencies.

His works were also shown at the prestigious Galerie Georges Petit. This gallery, established in the 1880s, became a major competitor to the Durand-Ruel gallery, which had championed the Impressionists. Galerie Georges Petit hosted significant exhibitions, including international expositions and solo shows for prominent artists. To have his work displayed here indicates a considerable level of recognition and success within the competitive Parisian art market. The fact that his paintings found their way into important public collections, such as the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the Musée de Tessé in Le Mans, further attests to the esteem in which his work was held. The Louvre, the national museum of France, acquiring his work would have been a significant honor, while regional museums like the Musée de Tessé played a crucial role in disseminating art and recognizing talent beyond the capital.

Contemporaries, Influences, and Artistic Dialogue

Pierre Gaston Rigaud operated within a rich ecosystem of artistic talent. His work inevitably entered into a dialogue with that of his contemporaries and predecessors. The towering figures of Impressionism—Claude Monet, with his series paintings of Rouen Cathedral or haystacks exploring light at different times of day; Camille Pissarro, with his vibrant cityscapes and rural scenes; and Alfred Sisley, with his delicate and atmospheric landscapes—undoubtedly provided a foundational influence regarding the treatment of light and color.

Among Post-Impressionists, while Rigaud may not have adopted the radical stylistic departures of a Van Gogh or a Gauguin, he would have been aware of their explorations into the expressive potential of color and form. The structural concerns of Paul Cézanne, who sought to "make of Impressionism something solid and durable, like the art of the museums," might also have resonated with Rigaud's own efforts to imbue his architectural scenes with a sense of permanence and gravitas.

Other artists of his era were also exploring similar themes or environments. Maurice Utrillo, for instance, though often associated with a more melancholic and linear style, frequently depicted Parisian street scenes and churches, capturing a unique sense of place. The Nabis, such as Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, were masters of intimate interiors and subtle light effects, though their focus was generally more domestic than Rigaud's grand ecclesiastical spaces. Even the Fauvist explosion of color led by Henri Matisse and André Derain in the early 20th century, while stylistically divergent, was part of the same artistic milieu in which Rigaud was working, a period characterized by bold experimentation and a redefinition of painting's expressive possibilities.

One might also consider earlier traditions. The architectural paintings of artists like Canaletto or Francesco Guardi, though from a different era and stylistic tradition (Venetian Vedutisti), set a precedent for the detailed and atmospheric depiction of significant buildings. Closer to his own time, the Romantic sensibility towards historic architecture, and the Gothic Revival, had fostered a renewed appreciation for medieval cathedrals, which artists like Rigaud then interpreted through a modern, light-focused lens. The Barbizon school painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, had also paved the way for a more naturalistic and light-sensitive approach to landscape painting, which informed the Impressionists and, by extension, artists like Rigaud.

The "Painter of Cathedrals": A Devotion to Sacred Luminosity

The moniker "painter of cathedrals" aptly captures the essence of a significant portion of Pierre Gaston Rigaud's artistic identity. His fascination with these monumental structures was not merely architectural; it was deeply connected to the way their interiors were transformed by light. Cathedrals, with their soaring vaults, vast spaces, and, most importantly, their stained-glass windows, offered a unique environment for the study of light's behavior – its diffusion, reflection, and refraction.

Rigaud's approach differed from, for example, Monet's famous series of Rouen Cathedral's facade, where Monet focused on the changing effects of light on the exterior stone at different times of day and under various weather conditions, often dissolving the solidity of the structure into a shimmering veil of color. Rigaud, by contrast, frequently ventured inside, exploring the interplay between the intricate architecture and the colored light that filled the space. His paintings often convey a sense of quiet contemplation, inviting the viewer to experience the serene and spiritual atmosphere of these sacred interiors. He was adept at rendering the textures of aged stone, the richness of wooden carvings, and the ethereal glow of light passing through glass, creating a harmonious synthesis of form and atmosphere.

This focus on cathedral interiors also allowed Rigaud to explore complex perspectives and compositions. The receding lines of columns, the arching of vaults, and the patterns created by aisles and transepts provided a rich framework for his studies of light and space. He managed to convey the immense scale of these buildings without sacrificing a sense of intimacy or human connection, often by subtly suggesting a human presence or by focusing on a particular chapel or detail that drew the viewer in. His work in this genre stands as a testament to his technical skill and his profound appreciation for the spiritual and aesthetic power of these enduring monuments.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Pierre Gaston Rigaud's contribution to French art lies in his sensitive and skilled interpretation of light and atmosphere, particularly within the unique context of cathedral interiors and in his evocative landscapes. While he may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of Picasso or Matisse, he was a master of his chosen domain, creating works that are both visually captivating and emotionally resonant. His paintings serve as a valuable record of French architectural heritage, viewed through the lens of late 19th and early 20th-century artistic sensibilities.

His ability to synthesize Impressionist concerns with light and Post-Impressionist attention to structure allowed him to create a body of work that is both immediate and enduring. The presence of his paintings in major collections like the Louvre ensures that his art continues to be accessible to the public and appreciated by scholars and art lovers alike. He successfully navigated the dynamic art world of his time, finding his own voice amidst a chorus of innovation, and leaving behind a legacy of luminous and contemplative art.

The enduring appeal of Rigaud's work stems from its quiet beauty and its profound respect for its subjects. In an era that often prized novelty and shock, Rigaud pursued a more introspective path, finding endless inspiration in the timeless interplay of light, stone, and nature. His paintings invite us to pause and observe, to appreciate the subtle nuances of color and atmosphere, and to connect with the enduring spirit of the places he depicted.

Conclusion: An Artist of Light and Place

Pierre Gaston Rigaud (1874-1939) remains a significant figure for his dedicated exploration of light, particularly within the hallowed spaces of French cathedrals and the diverse landscapes of his homeland. Emerging from an education in Bordeaux and maturing as an artist in the vibrant crucible of Paris, he skillfully navigated the currents of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, forging a personal style characterized by sensitivity, technical proficiency, and a profound appreciation for atmosphere.

His works, such as Cathédrale Saint-André, Vue du bassin d'Arcachon, and Chartres Cathedral at Three O’Clock, exemplify his mastery in capturing the ephemeral qualities of light while respecting the inherent structure and character of his subjects. Exhibiting at venues like the Salon des Indépendants and the Galerie Georges Petit, and with his art acquired by institutions including the Louvre, Rigaud achieved notable recognition in his lifetime. He contributed to a rich artistic dialogue with contemporaries ranging from the Impressionist masters like Monet and Pissarro to Post-Impressionist innovators and other painters of his generation who explored similar themes of light, architecture, and landscape.

As the "painter of cathedrals," Pierre Gaston Rigaud left an indelible mark, offering viewers a luminous window into the spiritual and aesthetic heart of these magnificent structures. His legacy is one of quiet dedication to his craft, resulting in a body of work that continues to resonate with its beauty, tranquility, and masterful depiction of light's transformative power.