Marius Borgeaud (1861-1924) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in Swiss Post-Impressionist painting. His oeuvre, characterized by a profound sensitivity to the nuances of interior spaces and the quiet rhythms of daily life, offers a unique window into the artistic currents of the early 20th century. Though he came to painting relatively late in life, his dedication and distinctive vision carved out a niche for him, particularly through his evocative depictions of Breton interiors and village scenes.

Early Life and an Unforeseen Detour

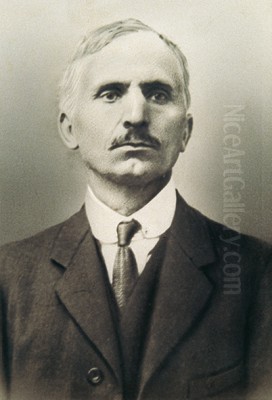

Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, on September 21, 1861, Marius Wilhelm Borgeaud hailed from a comfortable bourgeois family. His early education at the Industrial School in Lausanne did not initially point towards an artistic career. Instead, he embarked on a path in the financial sector, working for a bank in Marseille. This conventional start, however, was not to define his life's trajectory.

The inheritance of a substantial fortune following his father's death in 1888 enabled Borgeaud to lead a rather extravagant and pleasure-seeking lifestyle in Paris for nearly a decade. This period of indulgence, common among young men of means at the time, eventually took a toll on his health. By the turn of the century, around 1900, the consequences of this "vie de bohème" necessitated a period of recuperation. He underwent what was described as a "cure de désintoxication" (a detoxification cure) near Lake Constance, a pivotal moment that seems to have prompted a profound re-evaluation of his life's direction.

The Call of Art: Formal Training and New Beginnings

It was in the aftermath of this personal crisis, around the age of 40, that Borgeaud made the decisive shift towards art. He settled in Paris in 1901, a city then pulsating as the undisputed capital of the art world, teeming with revolutionary ideas and movements that were challenging academic traditions. Between 1901 and 1903, Borgeaud sought formal artistic training, enrolling in the ateliers of two prominent academic painters: Fernand Cormon and Ferdinand Humbert.

Fernand Cormon (1845-1924) was a highly respected historical painter whose studio was a veritable crucible for emerging talent. Cormon's atelier attracted a diverse array of students who would go on to make significant marks on art history, including such luminaries as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Vincent van Gogh, Émile Bernard, Louis Anquetin, and even, for a time, a young Henri Matisse. While Cormon himself adhered to a more traditional, academic style, his studio was known for fostering a degree of independent exploration among his pupils.

Ferdinand Humbert (1842-1934), another established academic artist known for his portraits and historical scenes, also ran a popular academy. Studying under these masters provided Borgeaud with a solid grounding in drawing, composition, and the traditional techniques of oil painting. This formal education, though rooted in academicism, would serve as a foundation upon which he would build his more personal, Post-Impressionist style.

Parisian Life and Artistic Development

Living in Paris, Borgeaud was inevitably exposed to the vibrant artistic milieu of the era. Impressionism, with pioneers like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas, had already revolutionized the art world with its emphasis on capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light. By the early 1900s, Post-Impressionist currents were in full swing, with artists like Paul Cézanne exploring structure and form, Paul Gauguin seeking spiritual and primitive expression, and Georges Seurat developing Pointillism. The Fauvist explosion, led by Matisse and André Derain, was just around the corner, challenging all conventions of color.

Borgeaud began to forge connections within this dynamic environment. He befriended several artists, including Henri Martin (1860-1943), a painter known for his idyllic, light-filled canvases often associated with Neo-Impressionism or a decorative Symbolism. It's documented that Borgeaud traveled through Italy with Martin for three years, an experience that would have further broadened his artistic horizons. He also formed a close friendship with Georges Picot, who would later play a role in the art market aspect of his career, and Thiébault-Sisson, a critic who wrote about his work.

During these formative years in Paris, Borgeaud began to develop his characteristic thematic interests. He was drawn not to grand historical narratives or overtly dramatic subjects, but to the intimate and the everyday. His focus sharpened on interior scenes, still lifes, and the quiet corners of domestic life, themes that would become hallmarks of his mature style. He produced over three hundred paintings in his lifetime, a testament to his dedicated, if later-starting, career.

The Brittany Years: A Defining Period

A significant chapter in Borgeaud's artistic development unfolded in Brittany. This region in northwestern France, with its distinct culture, rugged landscapes, and unique quality of light, had been attracting artists since the mid-19th century. The Pont-Aven School, famously associated with Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard, had already established Brittany as a place of artistic pilgrimage for those seeking authenticity and a departure from Parisian urban life.

Borgeaud made several extended stays in Brittany, particularly between 1908 and the early 1920s. He worked in various locations, including Rochefort-en-Terre in Morbihan, Le Faouët, and Audierne. It was in Rochefort-en-Terre, around 1908-1909, that he created two series of paintings that brought him considerable recognition and helped establish his reputation: one centered on the local town hall and the other on the village pharmacy. These works, often titled variations of "Le bureau de poste et la mairie de Rochefort-en-Terre" (The Post Office and Town Hall of Rochefort-en-Terre) and "La Pharmacie de Rochefort-en-Terre" (The Pharmacy of Rochefort-en-Terre), were exhibited at the prestigious Salon des Indépendants in Paris.

The Salon des Indépendants, founded in 1884 by artists like Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Odilon Redon, was a crucial alternative to the official, academically juried Salon. It operated under the motto "Sans jury ni récompense" (Without jury nor reward), allowing artists to exhibit freely and providing a platform for avant-garde movements. Borgeaud's success at the Indépendants with his Rochefort-en-Terre paintings marked a significant breakthrough, signaling his arrival as a painter of note.

His Breton interiors are particularly celebrated. He often depicted simple rooms, sparsely furnished, with figures engaged in quiet, everyday activities or simply existing within the space. There's a sense of stillness and contemplation in these works, a focus on the interplay of light and shadow, and a subtle psychological depth. He was less interested in the picturesque or folkloric aspects of Brittany that attracted some of his contemporaries, and more focused on the universal human experience within these specific, humble settings.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Marius Borgeaud is best categorized as a Post-Impressionist, though his style bears his distinct personal stamp. His work is characterized by a rich, yet often subtly modulated, color palette. He did not employ the broken brushwork of the Impressionists, nor the vibrant, non-naturalistic colors of the Fauves. Instead, his application of paint was generally smooth and deliberate, building up forms with a sense of solidity and structure that perhaps owes something to Cézanne's influence, albeit indirectly.

His compositions are often deceptively simple, yet carefully constructed. He had a keen eye for the geometry of interiors – the angles of walls, the placement of furniture, the fall of light through a window. Figures within these spaces are typically rendered with a certain directness and lack of idealization, contributing to the overall sense of authenticity. There's a quiet dignity to his subjects, whether they are peasants, local officials, or simply individuals caught in a moment of repose.

A recurring motif in Borgeaud's work is the interplay between interior and exterior, often suggested by a window or an open door that allows a glimpse of the world outside, or lets light flood into the room. This device not only adds visual interest but also creates a sense of connection between the intimate, private space and the larger environment. His paintings often evoke a feeling of tranquility, sometimes tinged with a gentle melancholy or a sense of timelessness.

While he is best known for his interiors, Borgeaud also painted landscapes and village scenes. His approach to these subjects shared the same qualities of careful observation, strong composition, and a focus on capturing the essential character of a place. His work can be seen in dialogue with other artists who explored intimate interior scenes, such as Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard of the Nabis group, though Borgeaud's style is generally more restrained and less overtly decorative than theirs. He shares with them, however, an interest in the poetics of domestic space.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Beyond the celebrated Rochefort-en-Terre series, several other works exemplify Borgeaud's artistic vision.

"L'Arrivée" (The Arrival), painted in 1920, is a fine example of his interest in everyday scenes, possibly depicting a moment at a rural train station or inn, a common theme reflecting the comings and goings of village life. Such scenes allowed him to explore human interaction and the atmosphere of semi-public spaces.

"Intérieur au chat" (Interior with Cat), from 1918, showcases his mastery of the interior genre. The presence of a cat, a common domestic animal, adds a touch of warmth and familiarity to the scene. Borgeaud was adept at capturing the textures of fabrics, the play of light on wooden furniture, and the overall ambiance of a lived-in space.

The series "La consultation" (The Consultation) and "Le mal de dents 1911" (The Toothache, 1911) further demonstrate his focus on human situations within specific settings. These works, likely also stemming from his Breton period, capture moments of vulnerability or everyday drama with a characteristic blend of empathy and detached observation. The titles themselves – "bistrot," "table," "salon," "accordéon" – often simply named the subject, underscoring his direct, unpretentious approach to his art.

His paintings are not narrative in an overt sense; they do not tell complex stories. Instead, they offer glimpses into moments, inviting the viewer to contemplate the scene and imbue it with their own interpretations. The power of his work lies in its ability to elevate the ordinary, to find beauty and significance in the unadorned realities of life.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Years

Borgeaud's work gained recognition through regular exhibitions, primarily in Paris. His participation in the Salon des Indépendants was crucial, but he also exhibited at the Salon d'Automne, another important venue for progressive art, founded by artists like Georges Rouault, André Derain, Henri Matisse, and Albert Marquet. He was also involved with Swiss artistic circles, exhibiting with organizations such as La Société des peintres, sculpteurs et architectes suisses (Society of Swiss Painters, Sculptors, and Architects).

Despite achieving a degree of success and critical acclaim during his lifetime, Borgeaud remained a somewhat reserved figure, dedicated to his craft. He continued to divide his time between Paris and Brittany, finding ongoing inspiration in the landscapes and interiors of the latter. His commitment to his chosen themes and his consistent stylistic development mark him as an artist of integrity and singular vision.

Marius Borgeaud passed away in Paris on May 16, 1924, at the age of 62. He left behind a body of work that, while perhaps not as widely known internationally as some of his more famous contemporaries, holds an important place in the history of Swiss art and Post-Impressionism.

Legacy and Art Historical Evaluation

In the decades following his death, Marius Borgeaud's reputation has steadily grown. His paintings are now held in numerous public and private collections, including significant holdings in Swiss museums such as the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne (Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts, Lausanne) and the Musée d'art de Pully. Retrospectives and scholarly publications have further illuminated his contribution to early 20th-century art.

Borgeaud's art offers a counterpoint to some of the more radical avant-garde movements of his time. While he was aware of Cubism, Fauvism, and emerging abstraction, his own path remained rooted in a figurative tradition, albeit one infused with modern sensibilities regarding color, composition, and emotional expression. His work can be seen as part of a broader Post-Impressionist tendency that sought to move beyond the purely optical concerns of Impressionism towards more subjective and structured forms of representation.

He shares with fellow Swiss Post-Impressionists like Félix Vallotton (though Vallotton's style is often harder-edged and more psychologically charged) and Cuno Amiet a commitment to exploring modern artistic language while retaining a connection to observable reality. Borgeaud's particular strength lay in his ability to convey a profound sense of place and atmosphere, particularly in his beloved Breton interiors. These works resonate with a quiet intensity, capturing the dignity of simple lives and the subtle beauty of everyday environments.

His influence, while perhaps not as direct or widespread as that of major innovators, can be seen in the continuing tradition of intimate interior painting and the appreciation for art that finds its subject matter in the unassuming aspects of life. Marius Borgeaud's legacy is that of an artist who, after a late start, pursued his vision with unwavering dedication, creating a body of work that is both deeply personal and universally appealing in its quiet humanity and refined aesthetic. He remains a testament to the enduring power of observational painting infused with genuine feeling.