Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Born in Leiden on October 20, 1640, and dying in the same city on November 7, 1691, Van Slingelandt dedicated his artistic life to the pursuit of meticulous detail and refined execution. He was a quintessential member of the Leiden "fijnschilders," or "fine painters," a group renowned for their highly polished surfaces, intricate rendering of textures, and intimate genre scenes or portraits. His legacy, though perhaps not as widely known as that of his direct master, is one of unwavering dedication to craft and an almost microscopic attention to the visual world.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Leiden

Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt was born into a craftsman's family in Leiden, a bustling center of textile production, academia, and, significantly, art during the 17th century. His father, Cornelis Pietersz van Slingelandt, was a stonemason, and his mother, Trijntje Jeroensdr, was the daughter of a shoemaker. This background, while not directly artistic, placed him within a milieu where skilled craftsmanship was highly valued. Leiden, home to a prestigious university and a thriving art market, provided fertile ground for aspiring painters.

The most crucial step in Van Slingelandt's artistic development was his apprenticeship under Gerard Dou (also known as Gerrit Dou). Dou, himself a former pupil of the great Rembrandt van Rijn, was the founding father and leading light of the Leiden fijnschilder school. Dou's studio was a hub of artistic activity, attracting numerous talented young men eager to learn his painstaking techniques. It was here that Van Slingelandt would have absorbed the core principles of the fijnschilder aesthetic: an emphasis on smooth, enamel-like surfaces, the precise depiction of fabrics, metals, and other materials, and the creation of small-scale, jewel-like paintings that invited close inspection.

The training under Dou was famously rigorous. Students were taught to grind their own pigments, prepare their panels (often copper or oak for their smooth surfaces), and apply paint in thin, almost invisible layers. Dou was known for his extreme patience and meticulousness, qualities that Van Slingelandt clearly inherited and perhaps even amplified. The studio environment would have been one of intense focus, with artists striving for perfection in every brushstroke.

The Leiden Fijnschilder Tradition

To understand Van Slingelandt, one must understand the Leiden fijnschilder movement. This school of painting, largely initiated by Gerard Dou after Rembrandt's departure for Amsterdam, distinguished itself from the broader, more painterly styles seen in other Dutch cities. The fijnschilders specialized in small-format genre scenes, portraits, and tronies (character studies of heads or figures). Their work was characterized by an astonishing level of detail, a smooth, polished finish that concealed brushwork, and often complex, subtly lit interior settings.

Key figures in this tradition, alongside Dou and Van Slingelandt, included Frans van Mieris the Elder, who was arguably Dou's most gifted pupil and a close contemporary of Van Slingelandt. Van Mieris achieved international fame for his elegant and exquisitely detailed depictions of affluent Dutch life. Other notable Leiden fijnschilders included Gabriël Metsu (though his style evolved to incorporate broader influences), Godfried Schalcken (known for his captivating candlelight scenes), Quirijn van Brekelenkam, Dominicus van Tol (Dou's nephew), and Ary de Vois. These artists, while each possessing individual nuances, shared a common commitment to refined technique and detailed realism.

The patrons of the fijnschilders were often wealthy burghers, merchants, and collectors who appreciated the skill, labor, and precious quality of these paintings. The works were not meant for grand public display but for intimate contemplation in private homes, often kept in special cabinets or behind curtains to protect their delicate surfaces. The high prices these paintings commanded reflected the immense time and effort invested in their creation.

Van Slingelandt's Artistic Style and Technique

Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt became one of the most dedicated exponents of the fijnschilder style. His technique was, by all accounts, exceptionally laborious. He worked slowly and methodically, building up his compositions with minute brushstrokes, often using fine brushes made from marten hair. This painstaking approach resulted in surfaces that were incredibly smooth, with an almost photographic clarity in the rendering of details. He excelled in depicting textures: the sheen of satin, the softness of velvet, the transparency of glass, the intricate patterns of lace, and the gleam of polished metal.

His subject matter primarily consisted of genre scenes and portraits. The genre scenes often depicted quiet domestic interiors, featuring figures engaged in everyday activities such as reading, sewing, music-making, or tending to children. These scenes, while seemingly straightforward, often carried subtle moralizing undertones or symbolic meanings, a common feature in Dutch Golden Age art. His portraits, though fewer in number, were equally characterized by their precision and careful attention to the sitter's likeness and attire.

Compared to his master Gerard Dou, Van Slingelandt's work can sometimes appear even more intensely focused on detail, occasionally at the expense of broader compositional dynamism or emotional depth. However, his sheer technical virtuosity is undeniable. He was a master of illusionism, creating a tangible sense of reality on a small scale. His palette was typically rich and harmonious, with a keen understanding of light and shadow to model forms and create a sense of space.

Key Works and Their Characteristics

While Van Slingelandt's oeuvre is not extensive due to his slow working method, several key works exemplify his style and skill.

One of his most celebrated paintings is "The Lacemaker" (circa 1670s), now housed in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden. This exquisite panel depicts a young woman diligently working at her lace pillow, a common subject for fijnschilders highlighting domestic virtue and industry. The painting is a tour-de-force of detailed rendering, from the individual threads of the lace and the texture of the woman's clothing to the various objects in the meticulously arranged interior, such as a discarded shoe, a basket, and a small dog. The play of light through the window illuminates the scene with a soft, diffused glow, typical of the Leiden school.

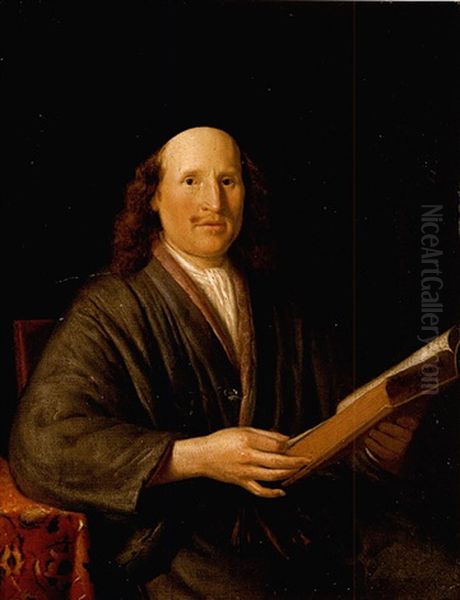

Another important work is his "Portrait of a Man Reading" (1668). This painting showcases Van Slingelandt's ability to capture a likeness with precision while also lavishing attention on the textures of the sitter's clothing and the surrounding objects, such as the book and the table covering. The introspective mood of the sitter is conveyed subtly, in line with the refined and understated nature of fijnschilder portraiture.

He also painted group portraits and family scenes, such as the portraits for the Van Musschenbroek family and those for Johan Hulshout and Anna Splinter. These works would have required immense patience from both the artist and the sitters, given Van Slingelandt's meticulous approach.

The portrait of "Francois Meerman" is particularly notable, not just for its artistic qualities but also for the legal dispute it engendered. This incident highlights the challenges faced by an artist whose working methods were so time-consuming.

His genre scenes often include charming details. For instance, "Young Woman Feeding a Parrot" demonstrates his skill in portraying not only human figures and their rich attire but also animals and still-life elements with equal precision. The parrot, a symbol of exoticism and wealth, is rendered with vibrant plumage, while the cage and other accessories are depicted with meticulous care. Such paintings appealed to the Dutch love for domesticity, order, and the subtle display of prosperity.

Patronage, Professional Life, and Anecdotes

Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt became a member of the Leiden Guild of St. Luke in 1661, a necessary step for any artist wishing to practice independently and take on pupils (though no pupils of Van Slingelandt are definitively known). He served as a "hoofdman" or dean of the guild in various years during the 1660s and 1670s, indicating his respected standing among his peers.

Despite his skill, Van Slingelandt's slow working pace meant that his output was limited, which in turn affected his income. Arnold Houbraken, an early biographer of Dutch painters, famously recounted anecdotes illustrating Van Slingelandt's extreme meticulousness. One story tells of him spending three years on a single portrait of the Meerman family. Another claims he dedicated an entire month to perfecting the lace on a ruff in a portrait of Johannes van Crombrugge. While possibly exaggerated, these stories underscore his reputation for painstaking labor.

The most well-documented anecdote concerns the portrait of Francois Meerman. Van Slingelandt reportedly took so long to complete the painting that the Meerman family grew impatient and eventually sued him. The court ultimately ruled in Van Slingelandt's favor, or at least a settlement was reached where the family had to pay a significant sum (reportedly 1200 guilders, though other sources mention 300 guilders for the painting itself, which was still a very high price). This incident reveals the tension between artistic perfectionism and the practical demands of patronage. Similar disputes arose over delays in delivering the portraits for Johan Hulshout and Anna Splinter.

His works, when completed, commanded high prices due to their exquisite quality and the labor involved. The French traveler Balthasar de Monconys, who visited Leiden in 1663, praised Van Slingelandt's work, noting its fine detail and comparing it favorably to that of Gerard Dou, though he also remarked on the high prices. This contemporary appreciation from a discerning foreign visitor attests to Van Slingelandt's growing reputation.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Van Slingelandt operated within a vibrant artistic community in Leiden. His primary influence was undoubtedly Gerard Dou. He would have also been keenly aware of the work of Frans van Mieris the Elder, whose elegant compositions and refined technique set a high standard for other fijnschilders. While not direct competitors in a hostile sense, these artists, along with others like Godfried Schalcken and Ary de Vois, formed a distinct school that shared common artistic goals.

Beyond Leiden, the broader Dutch art scene was flourishing. In Amsterdam, artists like Rembrandt (Dou's former master) continued to explore more expressive and dramatic styles. In Delft, Johannes Vermeer was creating his serene and light-filled interior scenes, which, while different in mood, shared a certain meticulousness and focus on domesticity with the Leiden school. Genre painters like Jan Steen (also active in Leiden for a period, though with a much more boisterous and satirical style), Adriaen van Ostade in Haarlem (known for his peasant scenes), and Gerard ter Borch in Deventer (famed for his elegant high-life genre scenes) were all contributing to the diverse landscape of Dutch Golden Age art.

While Van Slingelandt remained firmly rooted in the Leiden fijnschilder tradition, he would have been aware of these broader artistic currents through exhibitions, print reproductions, and the movement of artists and artworks between cities. His dedication to the "fine" manner of painting, however, remained unwavering throughout his career.

Personal Life and Later Years

Relatively little is known about Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt's personal life beyond his artistic endeavors. Unlike some of his contemporaries who achieved considerable wealth and social status, Van Slingelandt's income appears to have been more modest, likely a consequence of his slow production rate. He reportedly never married.

He continued to live and work in Leiden until his death on November 7, 1691. He was buried in the Hooglandse Kerk, a prominent church in Leiden, a resting place fitting for a respected citizen and artist. His dedication to his craft seems to have been the defining feature of his life.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt's legacy is that of a master of meticulous detail, a painter who pushed the boundaries of refined execution within the Leiden fijnschilder tradition. While his fame may have been somewhat eclipsed by that of Gerard Dou or Frans van Mieris the Elder, his works remain highly prized by connoisseurs and museums for their technical brilliance and exquisite beauty.

His limited oeuvre, a direct result of his painstaking methods, means that his paintings are relatively rare. Each surviving work, however, stands as a testament to his incredible patience and skill. In an era that valued craftsmanship and verisimilitude, Van Slingelandt delivered on both fronts, creating miniature worlds that continue to fascinate viewers with their intricate detail and jewel-like quality.

The appreciation for fijnschilder painting has fluctuated over the centuries. While immensely popular in their own time and throughout the 18th century, their highly detailed style fell somewhat out of favor during the 19th century with the rise of Romanticism and Impressionism, which valued broader brushwork and subjective expression. However, in more recent times, there has been a renewed appreciation for the technical mastery and unique aesthetic of the Leiden fijnschilders, including Van Slingelandt. His works offer a window into the domestic life, values, and artistic tastes of the Dutch Golden Age, rendered with a precision that still has the power to astonish.

Conclusion

Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt was an artist wholly dedicated to the ideals of the Leiden fijnschilder school. As a faithful pupil of Gerard Dou, he absorbed the techniques of meticulous detail, smooth finish, and intimate subject matter, and developed them with an almost obsessive precision. His paintings, though few in number due to his incredibly slow and laborious working process, are masterpieces of miniature realism. They capture the textures of fabrics, the play of light on surfaces, and the quiet moments of 17th-century Dutch life with unparalleled fidelity. While his career was marked by a painstaking approach that sometimes led to disputes with patrons, his commitment to artistic perfection resulted in works that continue to be admired for their exquisite craftsmanship and enduring charm, securing his place as a significant master of the Dutch Golden Age.