The early to mid-17th century in Antwerp marked a vibrant period in the history of Flemish art, a time when the city, despite political and economic shifts, remained a powerhouse of artistic production. Following the religious upheavals of the 16th century and the subsequent Spanish rule, Antwerp fostered a unique artistic climate. The Counter-Reformation fueled a demand for religious art, while a prosperous merchant class and nobility sought works for their private collections, leading to a remarkable specialization among painters. Within this dynamic environment, artists like Pieter Neefs the Elder, a master of architectural interiors, and Frans Francken the Younger, a versatile painter of diverse genres, carved out distinct yet interconnected careers. Their work not only reflects the artistic preoccupations of their time but also illustrates the collaborative nature of art production in 17th-century Antwerp.

Pieter Neefs the Elder: Illuminating Sacred Architecture

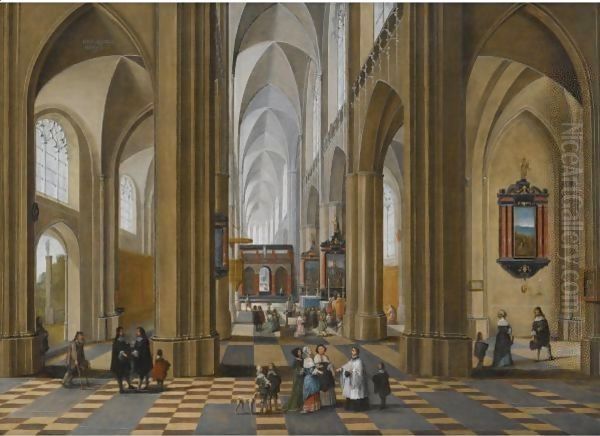

Pieter Neefs the Elder, born around 1578, emerged as one of the foremost painters specializing in church interiors, a genre that gained considerable popularity in the Low Countries. His life spanned a significant portion of the Flemish Golden Age, and he passed away sometime between 1656 and 1661, the exact date remaining a point of scholarly discussion. Antwerp, with its magnificent Gothic cathedrals and churches, provided the primary inspiration and subject matter for Neefs. He dedicated his artistic endeavors to capturing the solemn grandeur and intricate beauty of these sacred spaces, particularly the interiors of Antwerp Cathedral and St. Paul's Church.

Neefs's approach was characterized by an exceptional command of perspective, allowing him to render the deep, receding naves and complex vaulting of Gothic structures with convincing accuracy. His paintings are not mere architectural records; they are imbued with a palpable atmosphere, often achieved through his sophisticated handling of light and shadow. He masterfully depicted the subtle gradations of light filtering through towering stained-glass windows, illuminating specific areas while leaving others in evocative dimness, creating a sense of warmth, serenity, and divine presence. This careful modulation of light contributed significantly to the realistic and immersive quality of his works.

Early Influences and Artistic Development

The artistic formation of Pieter Neefs the Elder is thought to have been significantly shaped by Hendrick van Steenwijck the Elder (c.1550–1603), a pioneering figure in the genre of architectural painting. Van Steenwijck, who himself may have studied under Hans Vredeman de Vries, was renowned for his innovative depictions of imaginary and existing church interiors, characterized by their bright illumination and meticulous detail. It is highly probable that Neefs was a pupil or close associate of Steenwijck, absorbing his techniques in perspective and his approach to rendering architectural forms.

While Neefs's style bears resemblance to that of his presumed mentor, he developed his own distinct artistic voice. His works often exhibit a warmer palette and a more nuanced play of light, particularly in his nocturnal scenes or those illuminated by artificial light sources like torches or candles. These "night pieces" showcase his particular skill in capturing the dramatic effects of flickering light on the intricate surfaces of Gothic architecture, creating a sense of mystery and spiritual contemplation. His brothers, also painters, worked in a similar vein, but Pieter the Elder's output is generally considered superior in its refinement of detail and the subtlety of its atmospheric effects.

The Staffage: A Collaborative Endeavor

A common practice in 17th-century Flemish painting, particularly among specialists, was collaboration. Artists renowned for a specific skill, such as landscape, still life, or architecture, would often enlist other painters to add figures (staffage) to their compositions. Pieter Neefs the Elder frequently followed this practice. While he was the undisputed master of the architectural settings, the human figures that populate his church interiors were often painted by other artists.

Among his notable collaborators for staffage were members of the prolific Francken family, particularly Frans Francken the Younger, and also David Teniers the Elder (1582–1649). These figures, though small in scale relative to the imposing architecture, were crucial in animating the scenes, providing a sense of scale, and often introducing narrative elements, such as depictions of Mass, processions, or casual gatherings of worshippers and visitors. This division of labor allowed each artist to focus on their area of expertise, resulting in works of high overall quality. The seamless integration of figures by artists like Francken into Neefs's meticulously rendered spaces speaks to the close working relationships prevalent in Antwerp's artistic community.

Signature Works and Lasting Reputation

Pieter Neefs the Elder's oeuvre includes numerous depictions of church interiors, many of which are variations on favored views within Antwerp's principal churches. Among his most celebrated works is the Interior of a Gothic Church, dated 1605 and now housed in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden. This relatively early work already demonstrates his command of perspective and his ability to create a luminous, airy interior. Another significant piece is the Interior of St. Paul's Church, Antwerp, located in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, which showcases his mature style, with its rich detail and atmospheric depth.

His paintings were highly sought after during his lifetime and continued to be prized by collectors. They not only served as devotional aids or reminders of the beauty of sacred spaces but also as testaments to the civic pride associated with these magnificent structures. The enduring appeal of Neefs's work lies in his ability to combine technical precision with a profound sensitivity to the spiritual ambiance of his subjects. His dedication to this specific genre made him a leading figure within it, influencing subsequent painters of architectural scenes.

The Neefs Artistic Dynasty

The artistic tradition established by Pieter Neefs the Elder was continued by his sons, most notably Pieter Neefs the Younger (1620–after 1675) and Lodewijk Neefs (1617–c.1649). Pieter Neefs the Younger worked in a style very similar to his father's, often making it challenging for art historians to definitively attribute unsigned works to one or the other. He frequently collaborated with the same artists his father had, including Frans Francken III and David Teniers the Younger, for the staffage in his paintings.

Lodewijk Neefs also painted church interiors, though his output was smaller, and he seems to have been less prolific or perhaps his career was cut short. The continuation of the family workshop and specialization underscores a common pattern in early modern European art, where skills and artistic identities were often passed down through generations. The Neefs family, through the efforts of both the elder and younger Pieter, left an indelible mark on the genre of architectural painting, their works serving as quintessential examples of this Flemish specialty.

Frans Francken the Younger: A Prolific and Versatile Master

Frans Francken the Younger, born in Antwerp in 1581 and dying there in 1642, stands as one of the most significant and versatile painters of the Flemish Baroque. He hailed from an extensive and highly influential dynasty of artists, the Francken family, whose members were active as painters in Antwerp for over a century. His father, Frans Francken the Elder (1542–1616), was a respected painter of religious and historical subjects, and his uncles, Hieronymus Francken I (c.1540–1610) and Ambrosius Francken I (1544–1618), were also accomplished artists. This rich artistic heritage provided a fertile ground for Frans the Younger's development.

His early training was naturally undertaken within the family workshop, primarily under his father. It is also suggested that he may have spent time in Paris, possibly working in the studio of his uncle Hieronymus Francken I, who was active at the French court. This exposure to different artistic currents could have contributed to the breadth of his later output. By 1605, Frans Francken the Younger was registered as a master in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke, the city's venerable institution for artists and craftsmen. He quickly established a successful career, becoming dean of the guild in 1615, a testament to his standing within the artistic community.

A Wide-Ranging Repertoire

Unlike specialists such as Pieter Neefs the Elder, Frans Francken the Younger was remarkably versatile, excelling in a wide array of subjects and formats. He produced large-scale altarpieces for churches, depicting scenes from the Bible and the lives of saints, often characterized by dynamic compositions and a rich, vibrant palette. These works catered to the renewed demand for religious art during the Counter-Reformation. His historical and mythological paintings showcased his erudition and his ability to render complex narratives with clarity and dramatic flair.

However, Francken is perhaps best known today for his smaller, meticulously detailed cabinet paintings. These works, intended for the private collections of connoisseurs, covered an astonishing range of themes. He painted allegorical scenes, often imbued with complex symbolism and moralizing messages. His depictions of elegant companies, biblical parables, and scenes from everyday life (though often with an allegorical undertone) were highly popular. He was a key figure in the development and popularization of new genres that catered to the tastes of the burgeoning art market.

Innovations: Kunstkammer Paintings and Singeries

Frans Francken the Younger was an innovator, credited with popularizing, if not inventing, two distinctive genres: the Kunstkammer (or "art room") painting and the singerie (or "monkey scene"). Kunstkammer paintings depicted the lavish interiors of collectors' cabinets, showcasing an array of artworks, scientific instruments, natural curiosities, and other precious objects. These paintings were not only celebrations of wealth and learning but also complex allegories of art, science, and connoisseurship. Works like his Art and Curio Cabinet (various versions exist) are fascinating documents of contemporary collecting practices and intellectual interests. They often feature prominent figures of the day, including patrons and fellow artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625) and Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640).

Singeries were satirical scenes in which monkeys, dressed in human attire, mimicked human activities and follies. These whimsical and often humorous paintings provided social commentary, gently mocking human vanities and behaviors. Francken's singeries were highly imaginative and executed with a delicate touch, contributing to the popularity of this genre, which was later taken up by artists like David Teniers the Younger. These innovative themes demonstrate Francken's creative spirit and his responsiveness to the evolving tastes of his clientele.

Notable Compositions and Artistic Style

Frans Francken the Younger's style is characterized by its refined elegance, meticulous detail, and often a jewel-like quality in his smaller panels. His figures are typically slender and graceful, with expressive gestures and carefully rendered costumes. He employed a rich and varied color palette, often favoring luminous blues, reds, and yellows.

Among his many significant works, The Penitent Mary Magdalene visited by the Seven Deadly Sins (circa 1607-10) exemplifies his skill in combining religious narrative with allegorical content, rendered with exquisite detail. His Adoration of the Magi (various versions) showcases his ability to handle complex, multi-figure compositions with clarity and devotional feeling. Smaller cabinet pieces like The Triumph of Amphitrite (often depicting Neptune and Amphitrite) or The Resurrection of Lazarus highlight his narrative skill and his capacity for intricate detail on a small scale. His works often feature a smooth, enameled surface, a hallmark of Flemish cabinet painting.

The Francken Workshop and International Reach

Like many successful artists of his time, Frans Francken the Younger maintained a large and productive workshop. This workshop not only helped him meet the considerable demand for his paintings but also served as a training ground for other artists, including his own sons, Frans Francken III (1607–1667) and Hieronymus Francken III (1611–1671), who continued the family's artistic tradition. The workshop produced numerous versions and variations of his most popular compositions, a common practice that sometimes complicates attributions.

Francken's reputation extended beyond the Southern Netherlands. His works were actively collected throughout Europe, partly thanks to art dealers and merchants like Christian van Immerseel, who facilitated the export of Flemish paintings. This international demand underscores the widespread appeal of his art, which combined technical virtuosity with engaging subject matter. His influence was considerable, not only through his own prolific output but also through the dissemination of his stylistic innovations and thematic choices by his pupils and followers. He collaborated with numerous contemporaries, including still-life specialists like Frans Snyders (1579-1657) and landscape painters such as Abraham Govaerts (1589-1626) and Joos de Momper (1564-1635), further embedding his work within the collaborative fabric of Antwerp's art scene.

Converging Paths: Collaboration and Artistic Exchange in Antwerp

The art world of 17th-century Antwerp was characterized by a high degree of specialization and, consequently, frequent collaboration between artists. This practice was not seen as diminishing an artist's individual talent but rather as a pragmatic way to produce high-quality works efficiently, leveraging the specific skills of different masters. The relationship between architectural painters like Pieter Neefs the Elder and figure painters like Frans Francken the Younger is a prime example of this synergy.

The Nature of Artistic Partnerships

Painters specializing in architectural views, landscapes, or still lifes often lacked the inclination or the specific training to render human figures with the same proficiency as those who specialized in historical or genre scenes. Conversely, figure painters might not possess the meticulous skills required for complex perspective or the detailed rendering of inanimate objects. Thus, partnerships were mutually beneficial. The architectural painter provided the setting, and the figure painter, or "staffagist," populated it with lively human (or sometimes animal) figures that added narrative interest, scale, and often allegorical meaning.

These collaborations were facilitated by the close-knit nature of Antwerp's artistic community, centered around the Guild of Saint Luke. Artists often lived and worked in close proximity, fostering personal and professional relationships. The guild itself regulated artistic practices and standards, but it also provided a framework within which such collaborations could flourish. Artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder famously collaborated with Peter Paul Rubens, with Brueghel painting exquisite floral garlands around Madonnas or allegorical figures painted by Rubens. Similarly, landscape specialists like Jan Wildens (1586-1653) or Lucas van Uden (1595-c.1672) often had figures added to their scenes by artists such as Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678) or David Teniers the Younger.

Neefs and Francken: A Productive Alliance

The collaboration between Pieter Neefs the Elder and Frans Francken the Younger (and other members of the Francken family, including Frans Francken III) was particularly fruitful. Neefs's meticulously rendered church interiors provided ideal stages for Francken's elegant and expressive figures. Whether depicting a solemn Mass, a fashionable gathering, or biblical scenes set within contemporary ecclesiastical architecture, Francken's staffage animated Neefs's spaces, enhancing their narrative and visual appeal.

Specific examples of their joint efforts include numerous versions of Interior of a Gothic Church or Church Interior during a Service. In these works, Neefs would lay out the architectural framework with his characteristic precision, capturing the play of light on columns, vaults, and altarpieces. Francken would then populate the scene with groups of figures – priests officiating at the altar, elegantly dressed burghers in conversation, beggars seeking alms, or dogs wandering through the aisles. These figures are not mere accessories; they often contribute to the overall theme, perhaps contrasting worldly activities with the sanctity of the space, or illustrating different aspects of religious life.

The collaboration extended to Pieter Neefs the Younger, who, working in his father's style, also frequently relied on the Francken workshop, particularly Frans Francken III, for the figures in his paintings. This ongoing relationship between the two artistic families highlights the continuity of workshop practices and collaborative networks across generations.

Attribution Challenges and Artistic Dialogue

While collaboration was a hallmark of efficiency and quality, it can present challenges for modern art historians regarding attribution. In many cases, contracts or contemporary accounts might specify the roles of different artists. However, when such documentation is lacking, distinguishing the precise contribution of each hand, especially when styles were closely aligned or when workshop assistants were involved, can be difficult. The stylistic similarities between Pieter Neefs the Elder and his son, Pieter Neefs the Younger, further complicate matters, as do the various hands within the extensive Francken workshop.

Despite these challenges, the collaborative works of Neefs and Francken are a testament to a vibrant artistic dialogue. They represent a fusion of specialized talents, resulting in paintings that are richer and more complex than either artist might have produced alone. These works offer a window into the sophisticated tastes of 17th-century art collectors, who appreciated both technical mastery and engaging subject matter. The demand for such collaborative pieces underscores the value placed on this mode of production.

The Wider Artistic Context: Antwerp's Golden Age of Painting

The careers of Pieter Neefs the Elder and Frans Francken the Younger unfolded during a period of extraordinary artistic vitality in Antwerp. Despite the economic decline following the Dutch Revolt and the Scheldt blockade, the city remained a major cultural center, often referred to as the "Athens of the North." The Guild of Saint Luke was a powerful institution, and the city boasted an unparalleled concentration of artistic talent.

The Guild of Saint Luke and Artistic Specialization

The Guild of Saint Luke played a crucial role in regulating the art trade, training apprentices, and maintaining quality standards. Membership was essential for any artist wishing to practice independently or run a workshop. The guild's records provide invaluable information about the careers of artists like Neefs and Francken. The era saw a pronounced trend towards specialization. Artists focused on particular genres, such as history painting (the most prestigious), portraiture, landscape, seascape, still life (including flower pieces, banquet scenes, and market scenes), genre painting (scenes of everyday life), and architectural painting.

This specialization fostered a high level of technical skill within each genre. Besides Neefs, other notable architectural painters included Hendrick van Steenwijck the Younger (c.1580–1649), son of Neefs's presumed teacher, and later figures like Wilhelm Schubert van Ehrenberg (1630-c.1676). The Francken family itself represented a dynasty of versatile painters, but even within their broad output, individual members might lean towards certain themes.

Contemporary Masters and Their Influence

Antwerp in the first half of the 17th century was dominated by the towering figure of Peter Paul Rubens, whose dynamic Baroque style had a profound impact on Flemish art. His workshop was a major production center, and his influence was pervasive. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), Rubens's most gifted pupil, achieved international fame as a portraitist. Jacob Jordaens was another leading figure, known for his robust and lively history paintings and genre scenes.

While Neefs and Francken operated in different spheres than these giants of history painting, they were part of the same artistic ecosystem. The demand for diverse types of art meant there was room for many talents. Still-life painters like Frans Snyders, Jan Fyt (1611-1661), and Osias Beert (c.1580-1624) produced sumptuous depictions of game, fruit, and flowers. Adriaen Brouwer (1605/6-1638) and David Teniers the Younger excelled in peasant genre scenes. This rich tapestry of artistic production created a stimulating environment for all artists.

The Art Market and Patronage

The market for art in Antwerp was diverse. The Church remained a major patron, commissioning altarpieces and other religious works. The nobility and wealthy bourgeoisie were avid collectors, seeking paintings to decorate their homes and display their status and erudition. There was also a significant export market, with Antwerp paintings being shipped to Spain, France, England, and other parts of Europe. This robust demand supported the large number of artists active in the city and encouraged the production of a wide variety of artworks, from monumental canvases to small, precious cabinet pieces. The development of genres like the Kunstkammer painting by Francken directly reflects the interests and pride of these collectors.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Historical Nuances

The historical record for artists of this period is often incomplete, pieced together from guild records, inventories, and occasional contemporary mentions. While grand narratives of artistic genius are common, the day-to-day realities, workshop practices, and minor disputes often remain elusive or are colored by later interpretations.

Distinguishing Hands: The Neefs Conundrum

One of the persistent "controversies," or rather scholarly challenges, surrounding Pieter Neefs the Elder is the difficulty in distinguishing his work from that of his son, Pieter Neefs the Younger. Both specialized in the same subject matter, employed similar techniques, and often collaborated with the same staffage painters. Unsigned works, or those with ambiguous signatures (as both often signed "Pieter Neefs"), can be particularly problematic. While subtle differences in handling, palette, or atmospheric quality are sometimes proposed by experts, definitive attributions can remain elusive. This is less a "controversy" in the sense of a dispute and more a testament to the successful transmission of workshop style from father to son.

The provided information also notes that Pieter Neefs the Elder was not registered as an independent artist in the Guild of Saint Luke, which is an interesting point. This could imply several things: perhaps he worked for a period under another master (like Steenwijck) for longer than usual, or his primary income came through a workshop that was officially registered under another's name, or there's a gap in the surviving records. It doesn't necessarily diminish his skill or reputation, as his numerous surviving and often signed works attest to a successful career.

Francken's Innovations and Workshop Realities

Frans Francken the Younger's introduction and popularization of Kunstkammer paintings and singeries were significant contributions. These genres reflected a sophisticated, sometimes satirical, engagement with contemporary culture and collecting habits. The anecdote about a student mistaking a spider painting for Francken's own work (though the source text is slightly ambiguous if this refers to Francken the Elder or Younger) highlights the high degree of realism achieved by Flemish painters and the nature of workshop production, where students would copy masterworks. Such copies could be of high quality, leading to potential confusion.

The sheer volume of work produced by the Francken workshop, with its many family members and assistants, inevitably led to variations in quality and, occasionally, attribution issues. However, it also ensured the widespread dissemination of the Francken style and themes, solidifying the family's prominent place in Antwerp's artistic landscape.

The Business of Art and Collaboration

The collaborative nature of art production, as seen in the Neefs-Francken partnership, was a business reality. It allowed for efficient production and catered to market demands. While modern sensibilities often prioritize the singular genius, 17th-century patrons frequently valued the combined expertise of specialists. The "controversy" mentioned regarding competition between Neefs and Francken is more likely a reflection of the natural competitiveness within any thriving artistic market rather than specific documented disputes. Both artists, and their respective families, carved out successful niches. Their collaboration on specific pieces, such as the Interior of a Gothic Church or other church scenes, was a mark of this professional interaction, where Neefs provided the architectural shell and Francken (or his workshop) supplied the figures, a common and respected practice.

Conclusion: Enduring Legacies in Flemish Art

Pieter Neefs the Elder and Frans Francken the Younger represent two distinct but complementary facets of the rich artistic production of 17th-century Antwerp. Neefs, with his profound understanding of perspective and light, immortalized the solemn beauty of Gothic church interiors, creating spaces that were both architecturally precise and spiritually resonant. His dedication to this genre made him its preeminent Flemish master, his influence extending through his sons and shaping the way sacred architecture was depicted.

Frans Francken the Younger, on the other hand, was a protean talent, a master of multiple genres whose creativity and innovation left an indelible mark on Flemish painting. From grand altarpieces to intricate cabinet paintings, his work was characterized by elegance, narrative skill, and a keen observation of the world around him. His introduction of Kunstkammer paintings and singeries broadened the thematic repertoire of Flemish art, reflecting the intellectual and social currents of his time.

Their collaborations, and those with other contemporaries like David Teniers the Elder, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Hendrick van Steenwijck the Elder and Younger, and Tobias Verhaecht, highlight the interconnectedness of Antwerp's artistic community. In an era that valued both specialized skill and diverse subject matter, artists like Neefs and Francken thrived, their works sought after by a discerning clientele. They operated within a vibrant ecosystem that included giants like Rubens and Van Dyck, as well as a host of other talented painters such as Frans Snyders, Jan Fyt, Adriaen Brouwer, and Joos de Momper, each contributing to the city's artistic renown.

The legacies of Pieter Neefs the Elder and Frans Francken the Younger endure not only in the individual brilliance of their works but also in their exemplification of the collaborative spirit and specialized excellence that defined Flemish art in its Golden Age. Their paintings continue to captivate viewers with their technical mastery, atmospheric depth, and engaging narratives, offering a rich window into the artistic and cultural world of 17th-century Antwerp.