Introduction: A Flemish Talent in a Golden Age

The seventeenth century witnessed a remarkable flourishing of the arts across Europe, and the Southern Netherlands, particularly Antwerp, stood as a vibrant hub of creativity. Within this dynamic environment, Simon de Vos (1603-1676) emerged as a highly skilled and notably versatile painter. Active throughout the high Baroque period, De Vos navigated the rich artistic currents of his time, contributing significantly to history painting, portraiture, and the burgeoning field of genre scenes. Though often working in the immense shadow cast by his contemporary, Peter Paul Rubens, De Vos carved out a distinct and successful career, marked by technical proficiency, adaptability, and a keen understanding of the art market. His oeuvre reflects the energy, drama, and intellectual depth characteristic of Flemish Baroque art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Simon de Vos was born in Antwerp in October 1603. His father, Herman de Vos, was a dice maker, suggesting a background connected to skilled craftsmanship, a common thread in the families of many Antwerp artists. The city itself was a crucible of artistic innovation and commerce, still benefiting from the legacy established by earlier masters and energized by the towering presence of Rubens. It was within this stimulating milieu that the young Simon embarked on his artistic journey.

From approximately 1615 until 1620, De Vos served as an apprentice under the respected painter Cornelis de Vos. Interestingly, despite sharing the same surname, Simon and Cornelis were not related. Cornelis de Vos was himself a prominent figure, particularly renowned for his sensitive and insightful portraits, especially of children, as well as his historical paintings. This apprenticeship provided Simon with a solid foundation in the techniques and conventions of Antwerp painting, likely including drawing from life, paint preparation, and compositional principles. The influence of Cornelis's clear, descriptive style can sometimes be discerned in Simon's handling of figures and textures.

In 1620, having completed his training, Simon de Vos achieved a crucial milestone: he was registered as a master in the prestigious Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke. Membership in the Guild was essential for any artist wishing to practice independently, take on pupils, or sell their work within the city. This recognition marked the official beginning of his professional career, allowing him to establish his own workshop and begin building his reputation.

Early Stylistic Development: Mannerist Echoes and Cabinet Paintings

In the initial phase of his independent career, roughly spanning the 1620s, Simon de Vos primarily focused on small-scale paintings, often executed on panel or copper. These works, frequently referred to as cabinet paintings due to their intimate size suitable for private collectors' cabinets, often displayed characteristics inherited from late Mannerism, a style that lingered in Antwerp even as the Baroque gained ascendancy.

His early compositions could feature somewhat elongated figures, intricate arrangements, and a bright, sometimes jewel-like palette. The attention to detail in fabrics, objects, and settings was already evident. Art historians have noted stylistic affinities in these early works with painters like Frans Francken the Younger, another Antwerp master known for his detailed small-scale historical and allegorical scenes, often packed with figures and narrative incident. Some scholars also suggest parallels with the German-born painter Johann Liss, who worked in Italy and whose style blended Northern detail with Venetian colour and light, though Liss's direct influence on De Vos is less certain than that of local figures like Francken. These early works often tackled religious or mythological subjects, executed with a meticulous finish.

The Influence of Rubens and the High Baroque

No painter working in Antwerp during the first half of the seventeenth century could escape the pervasive influence of Peter Paul Rubens. While historical records don't definitively confirm a formal apprenticeship in Rubens's bustling workshop, the impact of the older master's style on Simon de Vos is undeniable and profound. It's highly likely De Vos had access to Rubens's work, perhaps even collaborating on minor aspects of larger commissions or simply absorbing the dynamic energy emanating from the city's dominant artistic force.

De Vos assimilated key elements of Rubens's High Baroque manner. This included a move towards more dynamic and dramatic compositions, a richer and more resonant colour palette, and a more vigorous, albeit often more controlled, brushwork. The use of expensive pigments, such as lapis lazuli for brilliant blues, seen in the works of both artists, points to shared workshop practices or aspirations towards a similar level of luxurious finish. De Vos particularly embraced the expressive potential of the Baroque, infusing his figures with greater movement and emotional intensity, especially in his history paintings.

This stylistic proximity, however, led to a recurring issue throughout De Vos's career and beyond: the misattribution of his works. Numerous paintings by De Vos have historically been credited to Rubens or his immediate circle. While this speaks volumes about De Vos's technical skill and his successful absorption of the Rubenesque idiom, it also perhaps hindered the full recognition of his individual artistic identity during his lifetime and afterwards. Disentangling his hand from that of Rubens remains a challenge for connoisseurship.

Genre Scenes: Merry Companies and Everyday Life

Alongside his religious and historical works, Simon de Vos became particularly adept at producing genre scenes during the 1620s and 1630s. These paintings depicted scenes of everyday life, often featuring elegantly dressed figures engaged in leisure activities. "Merry companies," showing groups enjoying music, card games, or conversation in domestic interiors or garden settings, were a popular theme.

De Vos excelled in capturing the textures of rich fabrics, the glint of metal objects, and the convivial atmosphere of these gatherings. His figures, while sometimes retaining a slightly mannered elegance, interact within well-defined spaces, showcasing his skill in perspective and spatial composition. Works depicting fortune tellers, such as the painting known as Reading the Palm or The Fortune Teller (Leitura da Sina), were also part of this repertoire, blending genre elements with a hint of the exotic or mysterious.

In developing these themes, De Vos participated in a broader trend popular across the Low Countries. Artists like Willem Buytewech in the Northern Netherlands, and closer to home in Antwerp, Adriaen Brouwer (known for his more rustic peasant scenes) and David Teniers the Younger (who depicted both peasant life and more elegant companies), were exploring similar subject matter. De Vos's contribution lay in his typically refined execution and elegant portrayal of the figures.

Allegory and Intellectual Depth: The Five Senses

The Baroque era delighted in allegory, using symbolic figures and objects to convey complex ideas or moral messages. Simon de Vos demonstrated his engagement with this intellectual aspect of art through works like his Allegory of the Five Senses. Several versions or related compositions exploring this theme are known, attesting to its popularity with his clientele.

In these paintings, De Vos typically personified the senses – Sight, Hearing, Smell, Taste, and Touch – through figures engaged in activities associated with each sense, surrounded by a wealth of symbolic objects. For instance, Sight might be represented by a figure looking in a mirror or at a painting, Hearing by musicians or listeners, Smell by flowers, Taste by food and drink, and Touch by stroking fabric or an animal. These works are often characterized by their intricate detail, rich colours, and sophisticated composition, inviting viewers to decode the layers of meaning embedded within the scene. They showcase De Vos's ability to combine meticulous observation with intellectual conceit, creating visually appealing and thought-provoking images.

The Stylistic Shift: Embracing History Painting Anew

Around the mid-1640s, a noticeable shift occurred in Simon de Vos's artistic production. While he did not entirely abandon other genres, his focus increasingly turned towards historical and religious subjects, often executed with a different stylistic emphasis. This later phase shows the discernible influence of another Antwerp giant, Anthony van Dyck, particularly Van Dyck's elegant portraiture and his more emotionally refined religious paintings.

De Vos's brushwork in this period could become smoother, his figures imbued with a greater sense of grace and psychological nuance, echoing Van Dyck's aristocratic sensibility. He continued to produce cabinet-sized pictures, but the compositions often gained in dramatic intensity and emotional weight. A key work representing this later style is The Beheading of St Paul. This painting exemplifies his mature approach to history painting, combining clear narrative, dramatic lighting, and figures expressing profound emotion, all rendered with considerable technical finesse.

Other significant works from this period include religious scenes like Christ on the Sea of Galilee (dated 1641, placing it near the beginning of this shift) and The Lamentation (1644). These paintings demonstrate his continued engagement with powerful biblical narratives, interpreted through the lens of the mature Flemish Baroque, balancing drama with a certain classical restraint likely absorbed from Van Dyck and the broader artistic currents of the time. Why he moved away from the popular genre scenes that had brought him success earlier remains a point of discussion among art historians, possibly reflecting changing market demands or a personal artistic evolution towards more 'elevated' subject matter.

A Master of Collaboration: Working with Specialists

The Antwerp art world fostered a remarkable culture of collaboration, where artists specializing in different areas would combine their talents on a single canvas. Simon de Vos actively participated in this practice, particularly in the creation of "garland paintings." This distinctive Flemish genre typically featured a central religious or mythological scene, often painted by a figure specialist like De Vos, surrounded by an elaborate wreath of flowers, fruit, or other objects painted by a still-life specialist.

De Vos is known to have collaborated frequently with Daniel Seghers, a Jesuit painter renowned for his exquisite flower garlands. Seghers would paint the intricate floral borders, while De Vos would execute the central devotional image, perhaps a Virgin and Child or a saint. These combined efforts resulted in works that were both pious and decorative, highly prized by collectors.

He also collaborated with Frans Snyders, the preeminent master of animal and market scenes, as well as opulent still lifes. While Snyders is more famous for his collaborations with Rubens, his partnership with De Vos likely involved similar divisions of labour, perhaps with De Vos painting figures within scenes dominated by Snyders's depictions of game, fruit, or animals. De Vos is also recorded as having worked with the landscape painter Alexander Keirincx, who would provide the landscape settings for De Vos's figures. These collaborations highlight De Vos's integration into the fabric of the Antwerp art community and the efficiency of its workshop system.

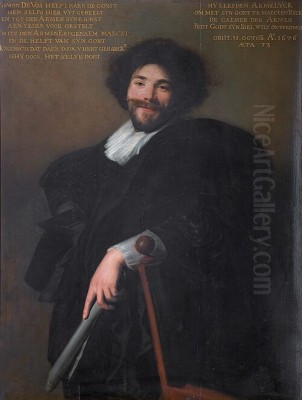

Portraiture: Capturing Likeness

While Simon de Vos is perhaps less celebrated for his portraiture than his teacher Cornelis de Vos or his contemporary Anthony van Dyck, he did engage with this genre. His portraits likely reflected the prevailing styles, influenced by the directness and psychological insight of Cornelis, the dynamism of Rubens, and the refined elegance of Van Dyck.

He would have aimed to capture not only a physical likeness but also the status and character of his sitters, employing the rich textures and sophisticated compositions characteristic of Flemish Baroque portraiture. Although fewer portraits are securely attributed to him compared to his history or genre paintings, they form part of his versatile output, demonstrating his ability to adapt his skills to different artistic demands. A potential self-portrait exists, offering a glimpse of the artist himself.

The Successful Professional: Art Dealer and Collector

Simon de Vos was not only a prolific painter but also a savvy professional who navigated the art market successfully. His marriage in 1628 to Catharina van Utrecht further cemented his ties within the artistic community; she was the sister of Adriaen van Utrecht, a prominent still-life painter known for his lavish banquet scenes and market stalls. This connection likely facilitated professional opportunities and collaborations.

Evidence suggests that De Vos achieved considerable financial success. He was a member of the Sodality of Bachelors (Sodaliteit van de Bejaerde Jongmans), a fraternity for unmarried men established by the Jesuit order in Antwerp, indicating a certain social standing. Furthermore, records indicate that he was not just a creator but also a collector and dealer of art. His own collection reportedly included works by other masters, reflecting his connoisseurship and engagement with the broader art world. His paintings found buyers not only locally but also internationally, with documented sales reaching markets as far away as Spain, attesting to his reputation beyond Antwerp.

Curiosities and Unanswered Questions

Like many artists from centuries past, Simon de Vos's life and work contain elements of intrigue and ambiguity. The precise reasons behind his stylistic shift in the 1640s remain open to interpretation – was it purely artistic evolution, a response to Van Dyck's immense popularity, or changing patronage demands?

The persistent confusion between his work and that of Rubens highlights the complexities of attribution and the subtle distinctions that define an individual hand within a dominant school. Furthermore, some scholars have pointed to intriguing, potentially symbolic details in his paintings that resist easy explanation. For example, discussions sometimes arise regarding specific iconographic elements, like the alleged hidden symbols on the garments of figures in certain religious scenes (such as the Pharisees in depictions of the Raising of Lazarus), although the precise meaning and intent often remain speculative.

Even the exact date of his death is subject to minor uncertainty. While generally accepted as occurring in Antwerp in 1676, with his burial recorded on October 15th of that year, some minor discrepancies in historical records have occasionally led to questions about the precise timeline of his final days. These small mysteries add layers to our understanding of the artist, reminding us of the gaps in the historical record and the ongoing process of art historical investigation.

Legacy and Influence: A Respected Antwerp Master

Simon de Vos occupies a significant position within the rich tapestry of seventeenth-century Flemish painting. While perhaps not reaching the towering international fame of Rubens or Van Dyck, he was a highly respected, technically accomplished, and remarkably versatile master who contributed substantially to the artistic life of Antwerp for over five decades.

His legacy is evident in several areas. Firstly, through his own extensive body of work, he demonstrated a mastery of multiple genres, from intimate cabinet paintings and lively genre scenes to dramatic historical narratives and sophisticated allegories. His ability to adapt his style, absorbing influences from Cornelis de Vos, Rubens, Frans Francken, and Van Dyck, while retaining his own careful execution, is notable.

Secondly, he played a role in artistic education, transmitting skills and styles to the next generation. Among his pupils was Jan van Kessel the Elder, who became known for his highly detailed studies of insects, flowers, and shells, often arranged in allegorical or scientific compositions. Van Kessel's meticulous technique may well owe something to the detailed finish often found in De Vos's own work.

His collaborations with specialists like Daniel Seghers, Frans Snyders, and Alexander Keirincx exemplify the cooperative spirit of the Antwerp school and resulted in unique hybrid works. His success as an artist and dealer also underscores the commercial vitality of the Antwerp art market. Ultimately, Simon de Vos stands as a testament to the depth of talent present in Antwerp during its Golden Age, a skilled painter whose works continue to be appreciated for their craftsmanship, narrative interest, and reflection of the Baroque era's aesthetic and intellectual concerns. He remains an important figure alongside his contemporaries, contributing to the enduring legacy of Flemish art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution to Flemish Baroque

Simon de Vos navigated the demanding and competitive art world of seventeenth-century Antwerp with skill and adaptability. From his early Mannerist-influenced cabinet pieces to his lively genre scenes and later, more dramatic historical and religious paintings, he demonstrated a consistent technical proficiency and a keen eye for detail. Influenced by, yet distinct from, masters like Cornelis de Vos and Peter Paul Rubens, and responsive to the elegance of Anthony van Dyck, he forged a successful career. His collaborations with leading specialists, his activities as a dealer, and his role as a teacher further underscore his significance within the Antwerp school. Though sometimes overshadowed by the era's giants, Simon de Vos left behind a rich and varied body of work that continues to engage viewers, offering valuable insights into the artistic dynamism and cultural life of the Flemish Baroque.