The 18th century in Britain was a period of profound social, intellectual, and artistic transformation. Amidst the burgeoning Enlightenment and the rise of the Royal Academy of Arts, figures emerged who navigated complex identities, bridging seemingly disparate worlds. One such compelling individual was the Reverend Matthew William Peters, an artist whose canvases often explored sensual and provocative themes, yet who also dedicated a significant portion of his life to the service of the Church of England. His journey from a promising painter of alluring portraits and genre scenes to a respected clergyman, even serving as a chaplain to royalty, offers a fascinating glimpse into the cultural dynamics and artistic currents of his time. Peters's legacy is marked by this intriguing duality, his artistic output celebrated for its charm and technical skill, while simultaneously inviting discussion about its relationship with his later ecclesiastical calling.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Matthew William Peters was born on the Isle of Wight, England, around 1742, though some accounts suggest an Irish birth. His early life, like that of many artists of the period, involved a foundational apprenticeship. He moved to London and became a pupil of Thomas Hudson, a prominent portrait painter who also famously taught Sir Joshua Reynolds. This early training under Hudson would have provided Peters with a solid grounding in the conventions of portraiture, a genre highly in demand among the British aristocracy and burgeoning middle class.

His talent was recognized early. In 1759, he received a premium from the Society of Arts, an institution established to encourage arts, manufactures, and commerce. This award was a significant early endorsement of his abilities. Seeking to further hone his skills and immerse himself in the classical tradition, Peters, like many aspiring British artists, embarked on a journey to Italy. The Grand Tour was considered an essential part of a gentleman's education and, for an artist, an indispensable pilgrimage to the heartlands of Renaissance and Classical art.

The Italian Influence and Academic Recognition

Peters's time in Italy, beginning around 1762, was formative. He spent time in Rome and Florence, diligently studying the Old Masters. In Florence, his talents gained him membership in the prestigious Accademia del Disegno, a clear indication of his growing reputation. The exposure to the works of Italian masters such as Titian, Correggio, and Veronese profoundly influenced his palette, his handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and his approach to the human form. He absorbed the rich colours and sensual textures that characterized much of Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, elements that would later become hallmarks of his own distinctive style.

Upon his return to England, Peters began to establish himself within the London art scene. He exhibited with the Society of Artists and later with the newly founded Royal Academy of Arts. The Royal Academy, established in 1768 with Sir Joshua Reynolds as its first president, quickly became the epicentre of artistic life in Britain. Peters's association with the Academy culminated in his election as an Associate (ARA) in 1771 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1777. This was a significant achievement, placing him among the leading artists of his day, alongside figures like Thomas Gainsborough, Benjamin West, and Angelica Kauffman.

A Distinctive Style: Sensuality and "Fancy Pictures"

While Peters undertook traditional portrait commissions, he became particularly known for his "fancy pictures" – genre scenes often imbued with a sentimental or, more notably, a subtly erotic charge. His depictions of women, in particular, were characterized by a soft, alluring quality. He often painted them in mythological or allegorical guises, allowing for a degree of nudity or déshabillé that might have been less acceptable in straightforward portraiture. His palette was warm, his brushwork fluid, and he excelled at rendering the soft textures of flesh and fabric.

Works such as A Lady in a Bacchante (or Portrait of a Lady as a Bacchante) and Miss Mortimer as Hebe exemplify this aspect of his oeuvre. These paintings, while drawing on classical iconography, possess a distinctly contemporary sensibility. The figures are often portrayed with a playful, sometimes provocative, gaze, engaging the viewer directly. Peters was adept at capturing a sense of intimacy and charm, but also a frisson of the risqué that appealed to the tastes of certain patrons.

His engagement with more overtly sensual themes is evident in works like The Fortune Teller and paintings depicting scenes from literature or history that allowed for dramatic and emotive compositions. Some of his works, particularly those featuring partially clad female figures, bordered on the titillating, leading to him being dubbed by some as the "English Titian" for his rich colouring and sensual forms, though perhaps without the profound depth of the Venetian master. He was certainly aware of the market for such pictures, and his patrons included influential figures like Lord Grosvenor, whose tastes may have encouraged Peters in this direction.

The Influence of Contemporaries and Masters

Peters did not operate in an artistic vacuum. He was, of course, influenced by his teacher Thomas Hudson, but the dominant artistic forces of his time were Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Reynolds, with his Grand Manner and intellectual approach to art, set a high bar for history painting and idealized portraiture. Gainsborough, on the other hand, was celebrated for his fluid brushwork, his sensitive portrayals, and his landscape painting. Peters, while carving his own niche, would have been acutely aware of their work and the broader European traditions.

His admiration for the Old Masters, particularly those of the Venetian school like Titian and Veronese, and Flemish masters like Peter Paul Rubens, is evident in his rich colourism and dynamic compositions. The influence of French Rococo painters like François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, with their playful eroticism and decorative charm, can also be discerned in some of Peters's more light-hearted and sensual works, though filtered through a distinctly British sensibility. He also engaged with literary themes, contributing works to John Boydell's famous Shakespeare Gallery, a major artistic project that involved many leading painters of the day, including Henry Fuseli, George Romney, and James Northcote.

The Transition to a Clerical Career

Perhaps one of the most intriguing aspects of Peters's life is his decision to take holy orders. Around 1781, he was ordained as a deacon and subsequently as a priest in the Church of England. This transition from a painter of sometimes risqué subjects to a clergyman was unusual, though not entirely unprecedented. It has been suggested that this career change might have been motivated by a desire for greater financial security or social standing, as ecclesiastical preferment could offer a stable income.

Despite his new vocation, Peters did not entirely abandon painting, at least not immediately. He continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy for some years after his ordination. However, the nature of his subjects began to shift. He increasingly turned to religious themes, producing altarpieces and other devotional works. Notable examples from this period include The Annunciation and The Spirit of a Child Arrived in the Presence of the Almighty. These works, while competent, perhaps lacked the vivacity and distinctive charm of his earlier secular paintings.

He held several ecclesiastical positions, including rectories at Litchborough in Northamptonshire, Scaldwell, and later at Knighton in Leicestershire and Woolsthorpe in Lincolnshire. He also served as a chaplain to the Prince Regent (later King George IV), a position that would have brought him into contact with the highest echelons of society. This royal appointment speaks to his respectability and connections, despite the sometimes-controversial nature of his earlier artistic output.

Notable Works and Artistic Themes

Rev. Matthew William Peters's oeuvre, though not as extensive as some of his contemporaries, contains several noteworthy pieces that highlight his artistic strengths and thematic preoccupations.

His portraits, such as those of Sir John and Lady Hopkins or the Children of Sir John and Lady Hopkins, demonstrate his skill in capturing a likeness and conveying a sense of character, albeit within the somewhat formal conventions of 18th-century portraiture. These works often display a warmth and an attention to the textures of fabrics and the play of light that elevate them beyond mere records of appearance.

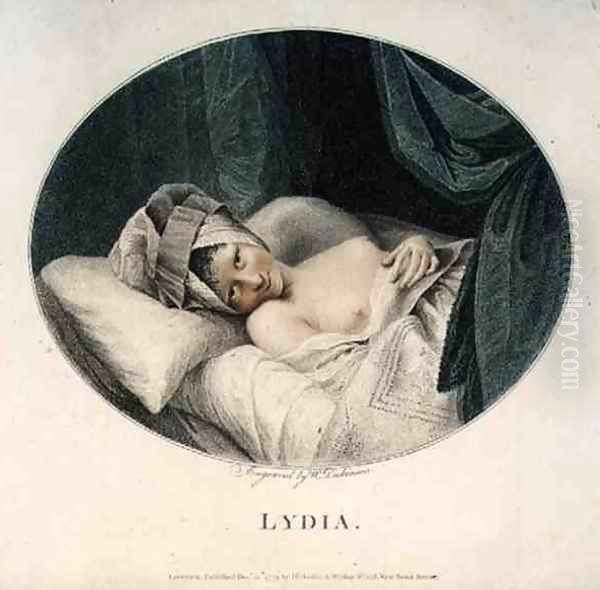

However, it is his "fancy pictures" and subject paintings that are often considered his most distinctive contributions. A Woman in Bed (sometimes titled Lydia or Venus in the Bed), is one of his most famous and, at the time, controversial works. Depicting a partially nude woman reclining seductively in bed, the painting is a clear essay in the sensual, drawing on a long tradition of reclining Venus figures but imbued with a contemporary directness. The soft modelling of the flesh, the rich draperies, and the intimate atmosphere are characteristic of Peters at his most alluring.

His contributions to Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery, such as scenes from Much Ado About Nothing or Henry VIII, allowed him to explore narrative and dramatic composition. While these works were part of a larger collective effort, they demonstrate his ability to engage with literary subjects and contribute to the burgeoning interest in history painting in Britain, a genre championed by Reynolds and Benjamin West.

Other significant works include Andromeda and Cleopatra and The Three Graces Decorating a Terminal of Hymen. These mythological and allegorical subjects provided ample opportunity for Peters to display his skill in depicting the female form and to create compositions rich in symbolism and decorative appeal. His handling of colour in these pieces is often vibrant, reflecting his study of Venetian masters.

Even after taking holy orders, his religious paintings, such as The Resurrection of a Pious Family and Cherubs, show a continuation of his soft style and warm palette, adapted to sacred themes. While perhaps not as groundbreaking as his secular works, they represent an important facet of his later career and his commitment to his religious calling.

The Art Scene of Peters's Era: A Wider Context

To fully appreciate Peters's position, it's essential to consider the vibrant and competitive art world in which he operated. The Royal Academy, under Sir Joshua Reynolds, was a dominant force, promoting academic principles and history painting. Reynolds himself was a master portraitist and a highly influential theorist. Thomas Gainsborough, Reynolds's great rival, offered a more poetic and less formal approach to portraiture and was a pioneer in British landscape painting.

Other notable figures included George Romney, whose elegant portraits rivaled those of Reynolds and Gainsborough in popularity. Joseph Wright of Derby became famous for his dramatic scenes illuminated by artificial light, often depicting scientific experiments or industrial subjects, as well as sensitive portraits. Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser were two female founding members of the Royal Academy, with Kauffman achieving international fame for her neoclassical history paintings and decorative schemes.

The Swiss-born Henry Fuseli brought a unique, often unsettling, vision to historical and literary subjects, particularly scenes from Shakespeare and Milton, characterized by dramatic intensity and elongated figures. Benjamin West, an American-born painter who succeeded Reynolds as President of the Royal Academy, was a leading exponent of neoclassical history painting, famous for works like The Death of General Wolfe. Johan Zoffany excelled in conversation pieces and theatrical scenes, capturing the social life of the era with wit and precision. These artists, and many others, contributed to a rich and diverse artistic landscape, providing both competition and inspiration for Peters.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Rev. Matthew William Peters occupies a curious and somewhat unique place in the annals of British art. His early success as a painter of charming and often sensual subjects, coupled with his later career as a clergyman, creates a narrative of intriguing contrasts. Historically, his work has sometimes been overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries like Reynolds and Gainsborough. However, there has been a renewed appreciation for his distinctive style and his contribution to the genre of the "fancy picture."

His willingness to engage with themes of sensuality and eroticism, particularly in works like A Woman in Bed, set him apart from many of his British contemporaries. While such themes were more common in French Rococo art, Peters adapted them to a British context, creating images that were both alluring and, for some, mildly scandalous. This aspect of his work has drawn attention from art historians interested in the representation of gender, sexuality, and the private lives of the 18th century.

The very fact that an artist known for such subjects could successfully transition into a career in the Church of England speaks volumes about the complexities and perhaps the hypocrisies of the era. It suggests that societal boundaries were, in some respects, more fluid than might be imagined, or that a certain degree of artistic license was tolerated, particularly if the artist later embraced a more conventional path.

His religious paintings, while perhaps less artistically innovative, are nonetheless an important part of his story. They reflect a sincere engagement with sacred themes and demonstrate his versatility as an artist. His service as a chaplain to George IV further underscores his acceptance within the establishment, despite the more provocative nature of his earlier artistic output.

In conclusion, the Reverend Matthew William Peters was more than just a minor painter of his time. He was an artist who skillfully navigated the demands of the art market, the expectations of patrons, and the evolving cultural landscape of 18th-century Britain. His ability to create images of enduring charm and sensual appeal, combined with his later commitment to a religious life, makes him a figure of considerable interest. His paintings, particularly his intimate and alluring depictions of women, continue to engage and sometimes provoke, securing his place as a distinctive voice in the rich chorus of 18th-century British art. His life and work remind us that artists often embody the contradictions and complexities of their age, leaving behind a legacy that invites ongoing interpretation and appreciation.