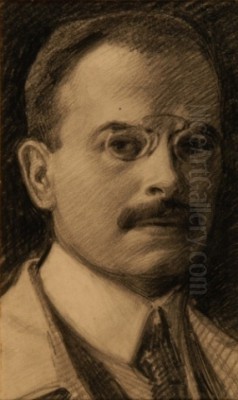

Richard Geiger (1870-1945) stands as a figure of considerable interest within the annals of art history, though the records surrounding his life and work present a multifaceted and sometimes perplexing picture. Identified primarily as a German artist, his career spanned a period of significant artistic transformation in Europe and beyond. His documented output includes at least 39 distinct works, showcasing a range of interests from figurative painting to more abstract explorations. His name resonates not only through his own creations but also through mentions by figures like Joan Carandell, who noted Geiger's skill in depicting interior scenes with notable finesse. The narrative pieced together from available sources suggests a life marked by diverse experiences and a broad spectrum of creative and intellectual engagement.

Understanding Geiger requires navigating accounts that sometimes offer contrasting details, painting a portrait of an individual whose path may have crossed geographical and disciplinary boundaries. From fine art to applied design, and potentially even into academic and professional realms outside of traditional art, the story of Richard Geiger unfolds as a compelling, if complex, tapestry woven from the threads of early 20th-century cultural and historical shifts. His legacy invites exploration into the various facets attributed to his name and work.

Origins and Formative Environment

The biographical details surrounding Richard Geiger's early life present an intriguing starting point, particularly regarding his origins. While often associated with the German art scene, specific records place his birth in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, in the United States. This account suggests roots in the American landscape, diverging from a purely European narrative. His heritage, according to these sources, traces back to Old Dutch lineage through his father, a man described as having spent his entire life in Pennsylvania.

This paternal figure is portrayed as settling on and improving a farm within the state, establishing a grounded presence. The family's background is further characterized by strong affiliations: they were devout Lutherans in their religious practice and staunch Republicans in their political leanings. This upbringing within a specific American cultural, religious, and political milieu would undoubtedly have shaped Geiger's early worldview and potentially influenced his later perspectives, even as his artistic identity became associated with German art circles. This duality between a documented American birth and a professional association with Germany adds a layer of complexity to his biographical narrative.

The environment described is one of stability and deeply held convictions. Growing up in a family rooted in Pennsylvania Dutch traditions, Lutheran faith, and Republican politics suggests an upbringing steeped in particular cultural values and community ties. These formative influences—the rural setting, the specific religious doctrines, the political climate of the time—would have formed the backdrop against which Geiger's own identity and aspirations began to take shape. How these early American roots intertwined with his later artistic path, particularly his association with German art, remains a fascinating aspect of his story.

Educational Pathways and Diverse Pursuits

The educational and professional trajectory attributed to the name Richard Geiger in various records further contributes to the complexity of his profile. One detailed account outlines the path of a Richard Allen Geiger, born much later, in 1939 in Alexandria, Louisiana. This individual received education in Roman Catholic schools, graduating high school in 1955. This narrative diverges significantly in time and place from the 1870-1945 artist, yet the information appears linked in the source material.

Following this educational line, the individual pursued higher education at Louisiana State University (LSU), initially earning a Bachelor of Science degree in Chemistry in June 1961. A significant shift occurred subsequently, as he undertook graduate studies in German and Linguistics within LSU's Department of Foreign Languages and Linguistics. This academic journey included a period abroad, studying German and Linguistics at the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg im Breisgau in Germany during 1963-1964.

Upon returning to LSU in 1965, this Richard Geiger continued his studies, eventually earning a Master of Arts degree in Linguistics and passing his doctoral qualifying examinations in 1966. His career path then led him into academia, starting as an instructor in Linguistics and Slavic Languages at the University of Missouri in 1966. He reportedly rose through the ranks to become an associate professor in 1969 and eventually a full professor. Records also mention a teaching position in German at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Adding another layer, separate mentions describe a Richard Geiger as a seasoned sales and customer service professional, holding a senior vice president role at Data Axle Nonprofit. This role involved providing strategic, analytical, and technical support to non-profit organizations. Furthermore, the academic Richard Geiger is noted as a co-author of a book titled "Philosophy and Language," published in 1993, and credited with numerous publications in academic journals and presentations at international conferences. Integrating these diverse educational and professional strands—artist, chemist, linguist, academic, sales executive—under the single name Richard Geiger (1870-1945) presents a significant challenge, suggesting either a remarkably varied life or a conflation of different individuals in the historical record.

Artistic Evolution: From Representation to Abstraction

Richard Geiger's artistic journey, as pieced together from available descriptions, appears to have encompassed a significant evolution in style and focus. Early references point towards a grounding in representational art. His skill in figure painting is noted, suggesting a command of traditional techniques and an interest in the human form. The mention by Joan Carandell specifically highlighting his nuanced portrayal of interior scenes further reinforces this aspect of his work, indicating an ability to capture atmosphere and detail within defined spaces.

However, Geiger's artistic path did not remain solely within the bounds of representation. Sources indicate a decisive move towards abstraction, aligning him with prominent currents in 20th-century art, particularly within the German context. This shift involved a deep engagement with the fundamental elements of visual art, most notably color and form. His exploration of color went beyond mere depiction, delving into its intrinsic qualities and visual effects.

This abstract phase saw Geiger experimenting with geometric shapes – rectangles, ovals, and circles became key components of his visual language. He utilized these forms not just as compositional elements but as vehicles to explore the expressive potential of color itself. This focus connects him to the broader movement of abstract art in Germany, where artists sought new ways to convey emotion and ideas, moving away from direct representation of the external world towards an exploration of inner realities and formal principles.

The Primacy of Color and Technical Innovation

Central to Geiger's abstract work was an intensive investigation into color. He is described as emphasizing color itself, exploring its inherent properties and psychological impact. This focus suggests an alignment with artists who saw color not merely as a tool for description but as the primary subject and expressive force within a painting. His approach involved studying how colors interact, their visual weight, temperature, and emotional resonance.

A particular affinity for the color red is noted in descriptions often associated with the Geiger name in abstract art contexts (though frequently linked specifically to Rupprecht Geiger). Red, in these interpretations, symbolized core aspects of existence: life, energy, power, love, warmth, and heat. Whether this specific focus applies directly to Richard Geiger (1870-1945) or is part of the conflation in records, the emphasis on color's symbolic and emotive power is a recurring theme.

Geiger's exploration was not limited to theoretical studies; it extended to technical innovation. He reportedly employed techniques like the "shaped canvas" (shaped canvas), where the physical shape of the canvas itself was altered to conform to or enhance the painted image. This method breaks from the traditional rectangle, allowing the color and form to dominate without the conventional constraints of the frame, pushing the boundaries between painting and object.

Further technical experimentation included the use of spray guns, allowing for smooth gradients and fields of color that differed from traditional brushwork. The incorporation of fluorescent pigments, specifically Daylight colors, is also mentioned. These pigments offered a luminosity and intensity beyond conventional paints, enabling the creation of works that seemed to emanate light, aiming for an almost non-material presence of color, detached from its physical carrier. These technical approaches underscore a commitment to pushing the expressive possibilities of his medium.

War, Surrealism, and Gothic Undertones

Geiger's artistic output is also described as being profoundly shaped by historical events, particularly the experience of war. Accounts place him as a "war painter" during World War II, creating works in Russia and Greece. This role suggests a direct confrontation with the realities of conflict, an experience that reportedly infused his art with a sense of immediacy and emotional weight. His depictions are said to convey the cruelty and intensity of war, often utilizing strong color contrasts to heighten the emotional impact.

Beyond the influence of war, Geiger's style is characterized in some sources by a unique blend of Surrealism and Gothic elements. This suggests an interest in the subconscious, dreamlike imagery, and perhaps a darker, more unsettling aesthetic. Descriptions mention themes of distorted landscapes and weaponry, elements often associated with Surrealist explorations of anxiety and the uncanny, as well as with Gothic traditions interested in the macabre and the sublime. This stylistic vein points towards an artist grappling with complex psychological and existential themes.

This fusion of styles reportedly extended beyond painting into other creative domains. Geiger is credited with work in sculpture, furniture design, and even interior design. This breadth suggests a holistic artistic vision, where the aesthetic principles explored in his paintings found expression in three-dimensional forms and spatial environments. The integration of Surrealist and Gothic sensibilities into applied arts would have resulted in highly distinctive and potentially provocative objects and spaces, blurring the lines between fine art and design. This aspect of his attributed work aligns him with artists like H.R. Giger, known for similar thematic concerns and cross-disciplinary practice, further adding to the complex web of attributions surrounding the Geiger name.

Materials and Methods

The materials and methods attributed to Richard Geiger reflect the diverse stylistic explorations mentioned in records. His connection to German abstract art is reinforced by references to his use of wood as a creative material. Working with wood, either as a support for painting or as a medium for sculptural forms, suggests an interest in tactile qualities and perhaps a connection to craft traditions, even within an abstract framework. This choice of material adds another dimension to his practice beyond conventional canvas painting.

The innovative technique of the "shaped canvas" stands out as a significant aspect of his methodology. By tailoring the canvas shape to the internal logic of the artwork, Geiger sought to enhance the impact of color and form. This approach challenges the traditional notion of the painting as a window onto another reality, instead emphasizing the artwork as a self-contained object with its own physical presence. It allowed color to assert itself more forcefully, unbounded by conventional rectangular limits.

The use of spray guns and fluorescent pigments represents another key technical aspect of his attributed work, particularly linked to the pursuit of pure color experiences. The spray gun facilitated the creation of uniform color fields and subtle gradations, achieving effects distinct from brushwork and contributing to a sense of dematerialized color. Fluorescent pigments, with their inherent luminosity, pushed this effect further, creating works that seemed to glow with an internal light, embodying the idea of color as an almost spiritual or energetic force independent of its material substrate. These techniques, often associated with post-war abstraction, highlight a forward-looking and experimental approach to art-making.

Documented Works and Exhibition Presence

While records mention a total of 39 works attributed to Richard Geiger (1870-1945), specific examples cited in the source material often correspond to pieces strongly associated with the later abstract artist, Rupprecht Geiger (1908-2009). Navigating this requires acknowledging the information as presented. Among the key works mentioned is 382/63, an oil painting from 1963. This piece, measuring 146 x 131 cm, achieved a significant auction result, selling for €174,000 against an estimate of €50,000, reportedly setting a record for a work of its size by the artist it is usually attributed to (Rupprecht Geiger).

Another cited work is G. 22/82. The information surrounding this piece is particularly contradictory. While mentioned alongside the high-value 382/63, suggesting significance, a separate description identifies G. 22/82 as a 1925 watercolor depicting street scenes in Rouen (Cuisiniers, Saint-Martin, Ste Catherine, Rue de l’Épicerie, Malpalec, Caen old houses). This watercolor is described as unsigned, measuring 30 x 40 cm, with a modest estimate of €100/200. This description starkly contrasts with the abstract, color-focused work typically associated with the Geiger name in post-war German art and seems chronologically and stylistically incongruous. Sources state no specific controversies are attached to this work's auction history.

Other representative titles linked to the Geiger name in abstract contexts include Ohne Titel (Untitled) from 1958, Superposition d'une répartition aléatoire de 20 carrés (Superposition of a random distribution of 20 squares) from 1971, and Rot (Red) from 2008. The dates of these works (especially 1958, 1971, 2008) fall well after the stated death date of Richard Geiger (1945), highlighting the persistent conflation in the source material.

Regarding exhibition history, the Geiger name (again, typically Rupprecht) is associated with significant platforms for modern and contemporary art. Participation in the prestigious Kassel Documenta exhibitions (specifically mentioned for 1964 and 1976 in some contexts related to Rupprecht) signifies recognition at the highest levels of the international art world. Exhibitions at venues like Galerie Waßermann in Munich and involvement with publications like Edition e, which produced portfolios of graphic works, further point to an active engagement with the gallery system and art market, primarily within the German post-war abstract scene.

Artistic Circles, Collaborations, and Influence

Richard Geiger's career, as depicted through the lens of German abstraction often associated with the name, placed him within significant artistic circles. He is linked to the founding of the influential post-war art group "ZEN 49." This group, reportedly co-founded with prominent artists like the ZERO group member Günther Uecker and the abstract painter Fritz Winter, played a crucial role in revitalizing abstract art in Germany after the cultural suppression of the Nazi era. ZEN 49 consciously sought to connect with the pre-war avant-garde, particularly the legacy of "Der Blaue Reiter" (The Blue Rider), the seminal group founded by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, which also included artists like August Macke and Paul Klee.

Beyond ZEN 49, Geiger is associated with the vibrant artistic environment of the Düsseldorf Art Academy, a major center for German art in the post-war period. While direct professorship is usually attributed to Rupprecht Geiger, the source material connects the Geiger name to this institution and mentions collaborations or collegial relationships with influential figures teaching there, such as Karl Haas and the highly influential performance artist and sculptor Joseph Beuys. This places Geiger within a dynamic network of artists shaping the future of German art.

His technical innovations, particularly the use of spray guns and fluorescent pigments, are noted as having influenced other artists. Figures like Thomas Lenk and Günter Fruhtrunk, known for their own explorations in geometric abstraction and color, are mentioned as having adopted similar techniques. This suggests Geiger was not only a creator but also a technical pioneer whose methods were disseminated within his artistic community. His connections extended internationally through participation in exhibitions like Documenta, fostering dialogue with artists globally. Furthermore, the initial mention by Joan Carandell suggests his earlier, perhaps more representational work, also garnered attention among contemporaries. The stylistic links to Surrealism might also imply an awareness of or dialogue with key figures of that movement, such as Salvador Dalí or Max Ernst, while the abstract elements resonate with broader movements like Abstract Expressionism, championed by artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

Expanding Creative Horizons: Design and Theory

The creative endeavors attributed to Richard Geiger were not confined solely to painting and sculpture. Sources indicate a significant engagement with applied arts and design. His involvement in furniture design and interior design suggests an ambition to extend his aesthetic principles into the lived environment. This aligns with a tradition of artists seeking to break down the barriers between fine art and everyday life, aiming for a unified aesthetic experience. Designing furniture and interiors allowed for the application of his ideas about form, color, and potentially the Surrealist or Gothic elements mentioned, into functional objects and spaces.

His work is also linked to architectural projects. A notable example, though typically credited to Rupprecht Geiger, involves design contributions to the Munich main train station (Hauptbahnhof). Such projects demonstrate a capacity to work on a large scale and integrate artistic concepts within public spaces. The use of color combinations and contrasts in architectural settings would serve as a public manifestation of the abstract principles explored in his studio work, transforming the urban environment.

Beyond visual creation, the Geiger profile incorporates intellectual and theoretical dimensions. The mention of Moritz Geiger, a scholar known for his work on music aesthetics and the philosophy of art (specifically his writings "The Aesthetic Enjoyment" and "The Meaning of Art"), hints at a possible intellectual environment or awareness of contemporary aesthetic debates. While Moritz is a distinct individual, his inclusion suggests the broader context of German philosophical and aesthetic thought during the period. Furthermore, the attribution of the book "Philosophy and Language" (1993) to the academic Richard Allen Geiger, mistakenly woven into the artist's narrative, adds another, albeit likely erroneous, layer of theoretical engagement to the composite profile.

Legacy and Enduring Impact

The legacy of Richard Geiger, as constructed from the available, often contradictory, sources, is multifaceted. On one hand, he is presented as a German artist (despite potential American origins) rooted in early 20th-century traditions, skilled in figure painting and interiors. On the other, he emerges as a key figure in post-war German abstraction, a pioneer of color theory, technical innovation (shaped canvas, spray gun, fluorescent paint), and a founding member of the influential ZEN 49 group. This abstract dimension connects him firmly to the lineage of German modernism, extending the legacy of groups like Der Blaue Reiter.

His influence is described as extending to contemporaries and subsequent generations of artists, particularly through his technical innovations adopted by figures like Thomas Lenk and Günter Fruhtrunk. His association with the Düsseldorf Art Academy, whether as professor (as often cited for Rupprecht) or collaborator with figures like Joseph Beuys, places him within a crucial pedagogical context, shaping future artists. The breadth of his attributed practice—spanning painting, sculpture, design, and architecture—suggests an artist who sought to integrate his vision across multiple domains.

Intriguingly, the source material also points to an unexpected legacy in popular culture. The mention of his style influencing tattoo art and motorcycle painting likely stems from the conflation with the Surrealist/Gothic elements, perhaps echoing the biomechanical aesthetic famously associated with H.R. Giger. While potentially a misattribution within the provided text, it highlights how artistic styles can permeate wider visual culture. The overall picture is one of complexity: an artist whose identity seems to bridge different eras, styles, geographical locations, and even disciplines, leaving behind a body of work and a narrative that invites further clarification while reflecting the rich, sometimes tangled, history of 20th-century art. His contributions, particularly in the realm of abstract art and color exploration, remain significant points of reference.