Robert Delaunay stands as a pivotal figure in the development of modern art in the early 20th century. Born in Paris on April 12, 1885, and passing away in Montpellier on October 25, 1941, Delaunay was a French artist who, alongside his wife Sonia Delaunay, co-founded the Orphism art movement. This movement, an offshoot of Cubism, prioritized pure abstraction and bright, harmonious colors, seeking to create paintings that resonated with the dynamism and rhythm of modern life. His exploration of color theory and geometric forms positioned him as a key innovator, bridging the gap between Cubism and fully abstract art, and leaving an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Robert Delaunay's entry into the world was into a milieu of Parisian upper-class comfort, yet his childhood was marked by familial disruption. His parents, George Delaunay and Countess Berthe Félicie de Rose, divorced when he was young. This led to him being primarily raised by his maternal aunt, Marie, and her husband, Charles Damour, at their estate, La Ronchère, near Bourges. This upbringing, while privileged, was perhaps less conventional than that of his peers.

Academically, Delaunay did not excel. His interests lay elsewhere, particularly in the visual arts. Recognizing his passion, he chose not to pursue traditional higher education. Instead, at the age of seventeen, he embarked on a practical path, apprenticing in 1902 at the Ronsin studio in Belleville, which specialized in painting theatrical scenery and stage sets. This early experience, working on a large scale and dealing with the immediate visual impact required for the stage, likely influenced his later bold use of color and form. He began painting seriously around 1903, signaling the start of a dedicated artistic journey.

Influences and Early Artistic Development

Delaunay's formative years as a painter were shaped by the vibrant artistic currents swirling through Paris at the turn of the century. He was particularly drawn to the scientific approach to color found in Neo-Impressionism, pioneered by artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Their technique of Pointillism, using small dots of distinct color to create a blended image in the viewer's eye, fascinated Delaunay. He absorbed their emphasis on optical mixing and the inherent luminosity of color.

Simultaneously, he studied the influential color theories of the 19th-century chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, particularly his principles of simultaneous contrast – the idea that colors appear different depending on the colors adjacent to them. This theoretical underpinning would become crucial to Delaunay's later work. He was also impacted by the bold, expressive colors of the Fauvist movement, led by Henri Matisse, and the structural investigations of Paul Cézanne, whose work laid foundations for Cubism. Delaunay began exhibiting his work early on, participating in the Salon d'Automne from 1904, a venue known for showcasing avant-garde art.

Engagement with Cubism

Around 1909, Delaunay began to engage deeply with Cubism, the revolutionary movement spearheaded by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Cubism challenged traditional perspective, breaking down objects into geometric facets and depicting them from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. Delaunay, however, approached Cubism with his own distinct sensibility, focusing less on the monochromatic palette and rigorous deconstruction of form favored by Picasso and Braque, and more on the dynamic interplay of color and light within a fragmented structure.

He associated with other artists exploring Cubism, including Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, who were part of the Puteaux Group (or Section d'Or). His works from this period, such as the Saint-Séverin series (1909-1910), depict the Gothic church interior through fractured planes, but infused with a vibrant, almost prismatic light and color that distinguishes them from mainstream Cubism. He sought to capture not just the structure, but the sensation and energy of the space through color contrasts.

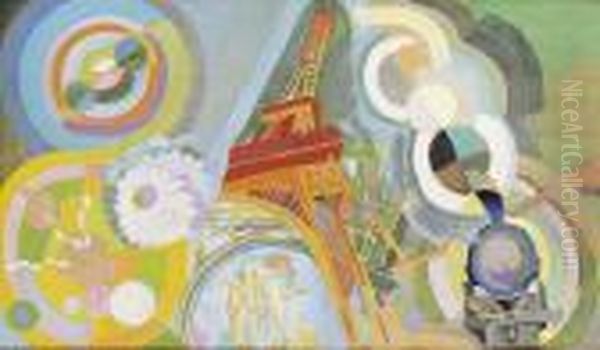

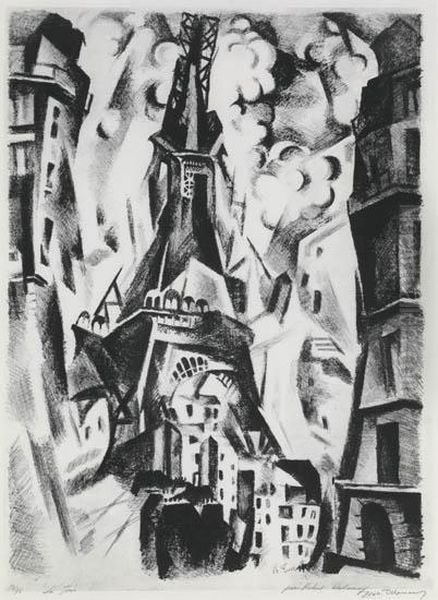

The Eiffel Tower: A Modernist Icon

Between 1909 and the late 1920s, the Eiffel Tower became a recurring and central motif in Delaunay's work. For him, this iconic structure was more than just an architectural landmark; it was a potent symbol of modernity, technology, and the dynamism of Paris. He painted it repeatedly, viewing it from different angles, under varying light conditions, and through the lens of his evolving style. He famously declared, "The Eiffel Tower is my barometer."

His early Eiffel Tower paintings (c. 1910-1911) show the influence of Cubism, depicting the tower as a fragmented, soaring structure, broken into geometric planes. However, unlike the often subdued palette of Picasso and Braque, Delaunay used increasingly vibrant colors, suggesting the energy and light surrounding the tower. These works capture a sense of upward movement and structural tension, reflecting an affinity with the dynamism celebrated by the Italian Futurists, such as Umberto Boccioni, although Delaunay developed his ideas independently. The series marks a crucial step in his move away from representational Cubism towards abstraction.

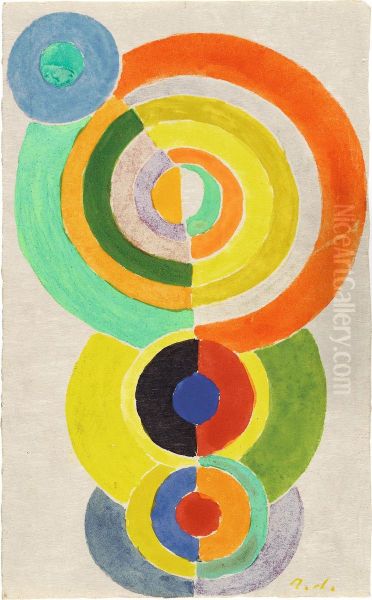

Orphism: The Art of Simultaneous Contrast

By 1912, Delaunay's experiments with color and form coalesced into a new artistic direction, which the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire termed "Orphism" or "Simultaneism." Apollinaire chose the name "Orphism," referencing the mythical Greek poet Orpheus, to emphasize the lyrical, musical, and purely abstract qualities of Delaunay's art. The movement, developed in close collaboration with Sonia Delaunay, aimed to achieve pure painting by abandoning recognizable subject matter entirely, relying solely on the interplay of colored geometric shapes – primarily circles and arcs – to create rhythm and depth.

Orphism was built upon Chevreul's theories of simultaneous contrast. The Delaunays believed that juxtaposing complementary colors (like red and green, or blue and orange) would create vibrant visual sensations, a sense of movement, and emotional resonance without resorting to narrative or representation. Key works from this period include Robert's Simultaneous Windows series (1912) and Circular Forms (begun 1912-1913), which feature interlocking discs and arcs of pure, radiant color. These paintings sought to capture the very essence of light and rhythm, creating an art form analogous to music.

Sonia and Robert: A Symbiotic Partnership

The artistic and personal relationship between Robert and Sonia Delaunay (née Terk) was exceptionally close and mutually influential. They met in 1909 and married in 1910, embarking on a lifelong collaboration that shaped the course of Orphism and extended its principles beyond painting. Their partnership was one of shared discovery and complementary talents. While Robert focused primarily on painting and theoretical explorations, Sonia applied their shared aesthetic to a wider range of media.

Together, they explored the concept of "simultaneity" not just in painting but in daily life. Sonia created "simultaneous dresses," patchwork clothing designs using geometric blocks of contrasting colors. She designed book bindings, textiles, costumes for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, and later, interiors and fashion boutiques. Robert, too, engaged in decorative projects and stage design. Their joint efforts blurred the lines between fine art and applied arts, demonstrating how abstract principles could permeate modern life. They exhibited together frequently, presenting a unified artistic front.

Wartime Exile and Continued Exploration

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 found the Delaunays vacationing in Spain. As Robert was declared unfit for military service, they remained in Spain and Portugal for the duration of the war, until 1920. This period of exile was challenging, particularly financially after the Russian Revolution cut off Sonia's family income. However, it was also artistically productive. The intense light and vibrant folk culture of the Iberian Peninsula influenced their palettes.

During this time, they continued to develop their theories of simultaneity. Sonia, in particular, flourished in applied arts, opening a boutique in Madrid, Casa Sonia, which featured her modern designs for fashion and interiors. Robert continued painting, exploring circular forms and rhythmic compositions, though perhaps with less intensity than in the pre-war years. They maintained contact with other artists and intellectuals who had also sought refuge from the war, fostering a small avant-garde community abroad.

Return to Paris and Later Career

Upon returning to Paris in 1920, the Delaunays found the art scene transformed by Dada and the nascent Surrealist movement. While they maintained connections with artists like Tristan Tzara and André Breton, their own work remained largely focused on the principles of Orphism and abstraction. Robert Delaunay entered a new phase, revisiting earlier themes but also exploring purely abstract compositions with renewed vigor.

His work in the 1920s and 1930s often featured large, rhythmic compositions of colored discs and arcs, sometimes re-engaging with the Eiffel Tower motif but in a more purely abstract manner. He became increasingly interested in large-scale public art. His most significant commission came in 1937 for the Paris International Exposition of Arts and Technology in Modern Life. He was tasked with creating vast murals for the Palais des Chemins de Fer (Pavilion of Railroads) and the Palais de l'Air (Pavilion of Air). These monumental works, such as Air, Fer et Eau (Air, Iron, and Water), were ambitious syntheses of abstract form, color, and modern themes, celebrating technology and progress. They brought his work significant public and international attention.

Interactions with Contemporaries

Throughout his career, Delaunay was deeply embedded in the Parisian avant-garde, interacting with many leading artists and intellectuals. His relationship with Cubism brought him into contact with Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, and Gleizes. While influenced by them, he maintained a distinct path focused on color. His exploration of color ran parallel to that of Henri Matisse, though their approaches and theoretical underpinnings differed.

His participation in the Blue Rider group's exhibitions in Munich (1911-1912) connected him with Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, key figures in German Expressionism and pioneers of abstraction. Kandinsky, in particular, shared Delaunay's interest in the spiritual and musical potential of abstract color. Guillaume Apollinaire was a crucial supporter, championing his work and providing the theoretical label "Orphism." Delaunay also knew Fernand Léger, who shared an interest in depicting modern, mechanical subjects. An early, perhaps formative, contact was with the naive painter Henri Rousseau, whose work Delaunay admired and whose painting The Snake Charmer (1907) was commissioned by Robert's mother. Later in life, he maintained connections with artists associated with Surrealism and abstraction, including Michel Larionov and Natalia Goncharova.

Controversies and Challenges

Delaunay's life was not without its difficulties and controversies. His decision not to return to France during World War I, although based on being declared unfit for service, led some to label him a deserter ("embusqué"), a stigma that lingered in some circles. Artistically, while respected, his work was sometimes overshadowed by the towering figures of Picasso and Matisse.

A notable anecdote highlights the sometimes-volatile nature of the Parisian art world. In the 1920s, Delaunay reportedly got into a physical altercation with the painter Georges Rouault over an artwork. Accounts suggest Rouault struck Delaunay, who retaliated, earning Delaunay the somewhat mocking nickname "Mr. Punch." This incident was interpreted by some as a clash between traditionalist (Rouault) and modernist (Delaunay) sensibilities, though personal animosity likely played a role. Financial struggles, particularly after the loss of Sonia's Russian income, were also a recurring challenge.

Final Years and Death

The late 1930s brought renewed recognition with the Paris Exposition murals, but also the looming threat of another war. Delaunay's health began to decline. Diagnosed with cancer, he and Sonia moved south to the Auvergne region as World War II began and German forces occupied Paris. He continued to work when his health permitted, focusing on abstract compositions. Robert Delaunay died of cancer in Montpellier on October 25, 1941, at the age of 56. Sonia worked tirelessly after his death to promote his legacy alongside her own continuing artistic career.

Family Background Revisited

Robert Delaunay hailed from an affluent background, with his father, George Delaunay, and mother, Countess Berthe Félicie de Rose, belonging to the Parisian elite. The early divorce of his parents, however, meant his upbringing was largely overseen by his maternal aunt and uncle, Marie and Charles Damour, in the Loire Valley. While details about his extended family are part of his biography, available historical records and biographical accounts do not mention Robert Delaunay having any children with Sonia or from any other relationship. His legacy is primarily artistic, carried forward through his work and Sonia's efforts.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Robert Delaunay's contribution to modern art is significant and multifaceted. As a pioneer of Orphism, he pushed the boundaries of Cubism towards pure abstraction, emphasizing the autonomous power of color and form to convey emotion and dynamism. His concept of "simultaneity," developed with Sonia, explored how contrasting colors could create visual rhythm and vibration, anticipating later developments in optical art.

His influence extended to numerous artists. Members of the Blue Rider group, like Kandinsky, Marc, and August Macke, were receptive to his color theories. Artists such as Paul Klee and Marc Chagall also showed affinities with his lyrical use of color. Later abstract movements, including Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, owe a debt to his early explorations of non-representational color composition. His work demonstrated that abstract art could be vibrant, optimistic, and deeply connected to the energy of modern life.

Today, Robert Delaunay's paintings are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Musée National d'Art Moderne (Centre Pompidou) and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. His Eiffel Tower series remains iconic, while his purely abstract Orphist works are celebrated as landmarks in the history of abstraction. He is remembered as a key innovator who fundamentally changed the way artists thought about color, light, and form.