Robert Hope (1869-1936) was a distinguished Scottish painter whose career spanned the late Victorian era, the Edwardian period, and into the interwar years. He carved a niche for himself primarily as a portraitist, particularly celebrated for his refined and sensitive depictions of women, though his oeuvre also included landscapes and genre scenes. His work is characterized by a subtle palette, an appreciation for texture and fabric, and an ability to capture the personality of his sitters, all hallmarks of the academic tradition blended with a gentle, observational modernism.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Edinburgh in 1869, Robert Hope emerged during a vibrant period in Scottish art. While specific details of his early training are not always exhaustively documented in readily accessible summaries, artists of his generation in Scotland typically sought instruction at one of the prestigious institutions like the Edinburgh College of Art (or its precursors) or the Glasgow School of Art. They would also often supplement their studies with travel to continental Europe, particularly Paris, to absorb the latest artistic developments, from the lingering influence of Impressionism to the nascent stirrings of Post-Impressionism and Art Nouveau.

Hope's development as an artist would have been shaped by the rich artistic environment of Scotland. The legacy of earlier Scottish portraitists like Sir Henry Raeburn (1756-1823) provided a strong foundation in characterful depiction. Contemporaneously, the "Glasgow Boys," including figures such as Sir James Guthrie (1859-1930) and Sir John Lavery (1856-1941), were revolutionizing Scottish painting with their embrace of realism and plein-air techniques, often influenced by French painters like Jules Bastien-Lepage. While Hope's style retained a more traditional elegance, the emphasis on capturing light and atmosphere prevalent in the work of his contemporaries likely informed his approach.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

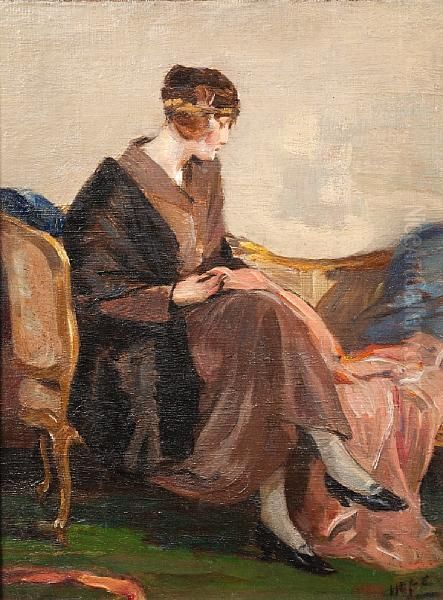

Robert Hope's artistic signature lies in his delicate and elegant approach, particularly evident in his portraiture. He possessed a keen eye for the nuances of human expression and the subtleties of personality, which he translated onto canvas with a refined technique. His portraits, especially those of women, often convey a sense of quiet introspection and grace. He was adept at rendering the textures of fabrics, as seen in works like "The Silken Gown," where the play of light on material becomes an integral part of the composition and the sitter's presentation.

His color palette was typically soft and harmonious, avoiding jarring contrasts in favor of a more unified and often gentle tonal range. This contributes to the overall sense of serenity and charm that pervades much of his work. While he was praised for his profound understanding of portraiture and his ability to capture a likeness that was both accurate and aesthetically pleasing, some critical assessments, perhaps viewing his work through the lens of more avant-garde movements, occasionally suggested that his draughtsmanship or expressive force might have been less overtly vigorous than that of some of his more radical contemporaries. However, the enduring appeal of his paintings underscores his skill in creating works of considerable artistic merit and sensitivity.

Beyond portraiture, Hope also engaged with landscape painting. Works such as "Ceres Mill, Fife" demonstrate his ability to capture the essence of the Scottish countryside. In these pieces, one can often see a similar attention to atmosphere and a carefully considered composition, though perhaps with a broader handling of paint compared to the meticulous detail of his formal portraits.

Key Works and Recognition

One of Robert Hope's most recognized works is "The Silken Gown." This painting exemplifies his skill in portraying feminine elegance and his mastery in depicting luxurious textiles. Its sale at Sotheby's in 2006 for £28,838 attests to the continued appreciation for his work in the art market. Such a price indicates a solid standing for a painter of his school and period, reflecting both the intrinsic quality of the piece and its representative nature within his oeuvre.

Another documented work, the oil painting "Ceres Mill, Fife," measuring 10" x 13" and noted with a sale price of £1,200, showcases his engagement with landscape. The choice of subject, a mill in the Fife region, connects him to a long tradition of artists depicting scenes of Scottish rural life and industry. The more modest price compared to "The Silken Gown" is typical for smaller-scale landscapes versus significant figural compositions by artists known primarily for portraiture.

Hope's achievements were recognized through his regular exhibitions, most notably at the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh. The RSA was, and remains, a cornerstone of the Scottish art establishment. To exhibit there consistently was a mark of professional standing and peer recognition. Artists like William McTaggart (1835-1910), known for his expressive seascapes and landscapes, and later the Scottish Colourists such as S.J. Peploe (1871-1935) and F.C.B. Cadell (1883-1937), also had strong associations with the RSA, highlighting its importance across different stylistic tendencies within Scottish art.

The Scottish Art Scene and Contemporaries

Robert Hope practiced his art during a period of significant artistic activity in Scotland. In Edinburgh, alongside the academic traditions upheld by the RSA, there was a distinct artistic identity. He would have been aware of, and likely interacted with, many leading figures. Besides those already mentioned, artists such as E. A. Walton (1860-1922), another of the Glasgow Boys known for his landscapes and portraits, or Robert Gemmell Hutchison (1855-1936), a contemporary known for his charming genre scenes of coastal life and children, were part of this vibrant milieu.

While the Glasgow School often garnered more international attention for its innovative spirit, Edinburgh maintained a strong tradition of portraiture and refined painting. Hope's work can be seen as part of this Edinburgh tradition, which valued skilled execution and psychological insight. His contemporaries in British portraiture more broadly included luminaries like John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), whose dazzling brushwork set a high bar, and Philip de László (1869-1937), his exact contemporary, who was renowned for his sophisticated portraits of European aristocracy and high society. While Hope's style might have been more restrained than Sargent's or de László's, he shared their commitment to capturing the essence of the sitter. Other notable British portraitists of the era included Sir William Orpen (1878-1931) and Solomon J. Solomon (1860-1927), whose works also reflected the diverse approaches to portraiture at the time.

Exhibitions and Institutional Presence

The primary venue for Robert Hope's exhibitions, as indicated by available information, was the Royal Scottish Academy. This institution played a crucial role in the careers of Scottish artists, providing a platform for them to showcase their work to the public, critics, and potential patrons. Regular inclusion in the RSA's annual exhibitions would have been vital for Hope's visibility and reputation. These exhibitions were major events in Scotland's cultural calendar, attracting widespread attention.

The information provided also mentions a connection to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City, suggesting he "curated Fritz's exhibition." This is an intriguing point. MoMA was founded in 1929, relatively late in Hope's career (he died in 1936). For a traditional Scottish painter to be curating an exhibition there, especially for an artist named "Fritz" (which is quite general), would be unusual without further specific context. It's possible this refers to a different Robert Hope, or perhaps a less formal advisory role, or that the details have become obscured over time. Typically, MoMA's early curatorial focus was on modern European and American art, often leaning towards the avant-garde. If Hope did have such a role, it would add a fascinating and somewhat unexpected dimension to his career, suggesting connections to the international modern art scene that are not immediately apparent from his primary artistic output. However, without more specific corroborating details for this Robert Hope, his strong and documented ties to the Royal Scottish Academy remain the most clearly defined aspect of his public and institutional presence.

Legacy and Later Assessment

Robert Hope's legacy is that of a skilled and sensitive painter, particularly in the realm of portraiture. He contributed to the rich tapestry of Scottish art at the turn of the 20th century, offering a vision of elegance and refined observation. His works, like "The Silken Gown," continue to be appreciated for their aesthetic qualities and their ability to evoke the spirit of their time.

While perhaps not an innovator in the mould of the more radical modernists, Hope excelled within his chosen idiom. His dedication to capturing the character and grace of his subjects, combined with his technical proficiency, ensured his place as a respected artist. The critique regarding a perceived lack of "expressiveness" or "sketching skills" in some quarters should be contextualized; artistic taste is fluid, and what might have seemed conventional to proponents of burgeoning modernist styles still represented a high degree of accomplishment within the traditions of representational painting and portraiture. His work provides a valuable window into the aesthetic sensibilities and societal values of Edwardian and early 20th-century Britain, particularly within the Scottish context.

Artists like Hope played an important role in maintaining and evolving the traditions of figurative art even as modernism began to take hold. His contemporaries included not only the aforementioned portraitists but also figures like George Henry (1858-1943) and E.A. Hornel (1864-1933) from the Glasgow School, who explored decorative and symbolic themes, often with rich color and texture, which Hope would have been aware of. The broader British art scene also included artists like Walter Sickert (1860-1942), whose gritty urban realism offered a stark contrast to Hope's more polished style, and Augustus John (1878-1961), known for his bohemian flair and expressive portraits.

Conclusion

Robert Hope stands as a notable figure in Scottish art history, a painter who navigated the transition from the 19th to the 20th century with a consistent commitment to elegance, craftsmanship, and insightful portraiture. His ability to capture the subtle nuances of personality and the allure of his subjects, often female, rendered in a soft, harmonious palette, defines his contribution. While his name may not be as widely recognized internationally as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, his work holds its own as a fine example of the enduring appeal of skilled representational art. His association with the Royal Scottish Academy and the continued presence of his works in collections and at auction affirm his status as a respected artist of his generation, a quiet master whose paintings continue to charm and engage viewers with their understated beauty and perceptive characterization. His art offers a refined counterpoint to the more turbulent artistic currents of his time, embodying a dedication to beauty and a deep appreciation for the human subject.