Robert Herdman (1829-1888) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century Scottish art. A painter of considerable talent and intellectual depth, he navigated the artistic currents of his time, producing a body of work celebrated for its sensitivity, historical engagement, and technical skill. Born in Rattray, Perthshire, Herdman's life and career were deeply intertwined with Scotland's cultural and academic institutions, yet his reputation extended beyond its borders, with his art gracing the walls of prestigious exhibitions in London and elsewhere. This exploration delves into the life, work, and artistic milieu of a man who was not only a gifted painter but also a respected scholar and antiquarian.

Early Life and Formative Education

Robert Herdman was born on September 17, 1829, in the small village of Rattray, Perthshire. His father, the Reverend William Herdman, was the minister of the local parish church, suggesting an upbringing within a household that valued learning and piety. The early death of his father in 1838 prompted the family's relocation to the historic town of St Andrews. This move proved pivotal for young Robert's intellectual development.

In St Andrews, Herdman enrolled at the Madras College, a well-regarded institution, where he studied for five years. His academic promise was evident early on, as he secured a scholarship that facilitated his further education. Following his time at Madras College, Herdman matriculated at the University of St Andrews. There, he pursued a full curriculum in the liberal arts, distinguishing himself in several classes and laying a broad intellectual foundation that would later inform his artistic practice. This classical education instilled in him a lifelong appreciation for literature, history, and ancient cultures, themes that would recur throughout his artistic career. Unlike many artists who focused solely on technical training from a young age, Herdman's university education provided him with a scholarly framework that enriched his choice of subjects and his interpretation of them.

Artistic Training and Influences

After completing his university studies, Herdman's inclination towards art led him to Edinburgh, the heart of Scotland's artistic establishment. He enrolled at the Trustees' Academy, the premier art school in Scotland, which had nurtured many of the nation's finest talents, including earlier luminaries like Sir David Wilkie and Alexander Nasmyth. At the Academy, Herdman came under the tutelage of Robert Scott Lauder, a charismatic and influential teacher who played a crucial role in shaping a generation of Scottish painters.

Lauder's teaching emphasized strong draughtsmanship, rich colour, and expressive composition. He encouraged his students to engage with literary and historical subjects, fostering an environment where narrative painting flourished. Herdman thrived under Lauder's guidance, and his fellow students included a remarkable cohort who would go on to achieve significant recognition, such as William Quiller Orchardson, John Pettie, William McTaggart, Peter Graham, Tom Graham, and George Paul Chalmers. This group, often referred to as "The Scott Lauder School," became a dominant force in Scottish art, and Herdman was a key member of this talented circle.

Beyond the immediate influence of Lauder, Herdman's art also shows an engagement with the broader currents of Victorian art, particularly the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. While not a formal member, his meticulous attention to detail, his preference for subjects with strong emotional or moral content, and his rich, luminous colour palette share affinities with the work of artists like John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Herdman, however, adapted these influences to his own temperament and Scottish context, creating a style that was distinctly his own, often imbued with a romantic sensibility and a touch of melancholy.

Themes and Subjects in Herdman's Art

Robert Herdman's oeuvre is characterized by its diversity, though certain themes and subjects recur, reflecting his personal interests and the tastes of his era. He was adept in various genres, including portraiture, historical scenes, literary illustrations, and, to a lesser extent, landscape.

Portraiture: Capturing Character and Grace

Herdman was highly regarded as a portrait painter, particularly renowned for his depictions of women and children. His female portraits are often characterized by their sensitivity, elegance, and psychological insight. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture not only a sitter's likeness but also their inner character, often imbuing his subjects with an air of gentle refinement or quiet contemplation. Works such as Sibylla (1872) exemplify this aspect of his art, presenting a figure that is both classically inspired and deeply human. His portraits were sought after, and he painted many prominent figures of Scottish society, contributing significantly to the visual record of his time. The delicate rendering of fabrics, the subtle play of light on skin, and the expressive gazes of his sitters are hallmarks of his portraiture.

Historical and Literary Narratives

Herdman's scholarly background and his passion for history and literature found vibrant expression in his narrative paintings. He was particularly drawn to subjects from Scottish history, classical antiquity, and romantic literature. One of his most significant commissions in this vein came in 1867-68 when the Art Union of Glasgow requested a series of four paintings illustrating episodes from the life of Mary, Queen of Scots. These works, which were later reproduced as an album accompanied by a poem, showcased his ability to handle complex historical narratives with dramatic flair and historical accuracy, resonating deeply with the Victorian era's fascination with Scotland's romantic past.

His engagement with classical themes is evident in paintings like Penelope (1876), depicting the faithful wife of Odysseus, and Antigone (1882), portraying the tragic Greek heroine. These works demonstrate his familiarity with classical literature and his skill in conveying the pathos and drama of ancient myths. Another notable early work, Excelsior (1850), was inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's popular poem, reflecting the period's taste for uplifting and allegorical subjects. These narrative paintings often featured meticulously researched costumes and settings, underscoring Herdman's commitment to historical verisimilitude.

Genre and Landscape

While portraiture and historical scenes formed the core of his output, Herdman also produced genre paintings and landscapes. His genre scenes often depicted moments of everyday life or poignant human interactions, treated with the same sensitivity and attention to detail as his more formal compositions. His landscapes, often executed in watercolour, captured the beauty of the Scottish countryside, particularly the autumnal scenery of regions like Lorne and Arran. These works are noted for their directness, their pure and harmonious colour, and their ability to evoke the specific atmosphere of the Scottish Highlands and islands. Though perhaps less central to his reputation than his figurative work, his landscapes demonstrate his versatility and his keen observation of the natural world.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of Herdman's paintings have achieved lasting recognition and are held in public collections, offering insight into his artistic achievements.

After the Battle: A Scene in Covenanting Times (1870, Scottish National Gallery): This is arguably one of Herdman's most famous works. It depicts a poignant scene in the aftermath of a conflict during the Covenanting period of Scottish history. A Covenanter, wounded and perhaps dying, is tended by his wife in a humble cottage, while another figure keeps watch. The painting is a masterful blend of historical narrative and human emotion, rendered with a subdued palette that enhances its sombre mood. The attention to historical detail in the costumes and setting, combined with the tender portrayal of the figures, made it a highly popular and affecting image. It resonated with Scottish national sentiment and the Victorian appreciation for scenes of heroism and domestic piety.

La Culla (The Cradle) (Scottish National Gallery): This work showcases Herdman's skill in depicting tender, intimate scenes. Likely a portrayal of maternal affection, it would have appealed to Victorian sensibilities regarding family and domesticity. The title itself, Italian for "the cradle," suggests a universal theme of new life and nurturing care, rendered with Herdman's characteristic sensitivity and refined technique.

Sibylla (1872): This painting of a classical prophetess is a fine example of Herdman's engagement with ancient themes and his skill in female portraiture. The Sibyl is depicted as a thoughtful, perhaps melancholic figure, her gaze distant as if contemplating a divine revelation. The rich drapery and the careful modelling of the features are typical of Herdman's style, blending classical idealism with a sense of individual character.

Penelope (1876): Inspired by Homer's Odyssey, this work portrays Odysseus's loyal wife, who famously awaited his return from the Trojan War. Herdman captures Penelope's steadfastness and perhaps her underlying sorrow, weaving a narrative of fidelity and endurance. Such classical subjects allowed artists like Herdman to explore universal human emotions within a framework of established literary tradition.

Tympanistria (1885): The title refers to a female player of the tympanon, an ancient frame drum or tambourine. This painting likely depicts a figure from antiquity, perhaps a participant in a religious procession or festival. It reflects Herdman's interest in classical culture and his ability to create evocative images of historical or mythological women, often with a focus on their grace and poise.

By the Woodside (1885): This title suggests a landscape or a genre scene set in a natural environment. Given Herdman's known skill in watercolour and his fondness for autumnal scenes, this work likely captured the beauty of the Scottish woodlands, perhaps with figures integrated into the setting, reflecting a quiet moment of rural life or contemplation in nature.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Professional Life

Robert Herdman was an active participant in the artistic life of his time. He regularly exhibited his works at the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh, a prestigious institution of which he became an Associate (ARSA) in 1858 and a full Academician (RSA) in 1863. His contributions to the RSA's annual exhibitions were numerous and well-received, solidifying his reputation within Scotland.

His ambitions, however, were not confined to his native land. Herdman also sought recognition in London, the dominant art centre of the British Empire. He exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA), with works such as a piece shown in the 1864 exhibition. While he did not achieve the same level of fame in London as some of his contemporaries, such as Orchardson or Pettie, his participation in RA exhibitions indicates his desire to engage with a wider audience and to measure his work against the leading artists of the day. He also exhibited at other venues, including the Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts.

Beyond his painting, Herdman was a respected figure in Edinburgh's intellectual circles. He was a member of the Edinburgh Hellenic Society, reflecting his enduring interest in Greek culture and literature. Furthermore, he served as Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, a role that underscored his scholarly engagement with history and archaeology. These intellectual pursuits undoubtedly enriched his art, providing him with a deep well of knowledge from which to draw his subjects and themes. His studio was not merely a place of artistic production but also a hub of scholarly inquiry.

Contemporaries and the Scottish Art Scene

Robert Herdman worked within a vibrant and evolving Scottish art scene. His primary mentor, Robert Scott Lauder, was a pivotal figure, and Herdman's career developed alongside those of his fellow students at the Trustees' Academy. This group, including William Quiller Orchardson, John Pettie, William McTaggart, Peter Graham, and George Paul Chalmers, collectively raised the profile of Scottish art. While their styles diverged over time – McTaggart, for instance, became a leading Scottish Impressionist, while Orchardson and Pettie achieved great success in London with their historical genre scenes – they shared a common foundation in Lauder's teaching.

Other notable Scottish contemporaries included Sir Noel Paton, known for his intricate historical, allegorical, and fairy paintings, who also served as Queen Victoria's Limner for Scotland. Sir George Harvey, a predecessor as President of the Royal Scottish Academy, was renowned for his scenes of Scottish life and history, particularly those related to the Covenanters, a theme Herdman also explored. Landscape painting flourished with artists like Horatio McCulloch, celebrated for his grand depictions of the Scottish Highlands, and Sam Bough, known for his vigorous and atmospheric watercolours and oils. Erskine Nicol, though often associated with Irish subjects, was also a prominent figure in the Scottish art world, known for his humorous and anecdotal genre scenes.

The influence of the English Pre-Raphaelites, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, was felt in Scotland, and Herdman's work, with its emphasis on detail, literary themes, and rich colour, shows an awareness of their ideals, even if he was not a direct follower. He navigated a path that respected academic tradition while being open to contemporary trends, contributing to a distinctly Scottish school of painting that was both national in its focus and international in its aspirations.

Later Life, Legacy, and Unfinished Work

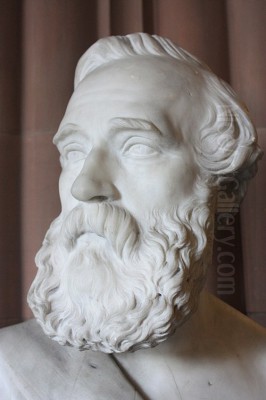

Robert Herdman remained a productive and respected artist throughout his life. His dedication to his craft was unwavering, and he continued to paint and engage with scholarly pursuits until his final days. His son, Duddingston Herdman, also became an artist, following in his father's footsteps. Portraits of Robert Herdman were created by contemporaries, including a sculpture by W. Brodie, R.S.A., indicating the esteem in which he was held.

Tragically, Robert Herdman's life was cut short. He died suddenly from heart disease in his studio in Edinburgh on January 10, 1888, at the age of 58. At the time of his death, he was reportedly preparing a manuscript for an "Address to the Students of the Board of Manufacturers' School of Art" (the formal name for the Trustees' Academy). This address, left unfinished, was published posthumously as a pamphlet in Edinburgh later that year, a testament to his commitment to art education and the guidance of young artists.

Robert Herdman's legacy is that of a quintessential Victorian Scottish artist: learned, skilled, and deeply engaged with the cultural and historical narratives of his nation. His works are preserved in major Scottish collections, including the National Galleries of Scotland, and continue to be appreciated for their technical accomplishment, their narrative power, and their sensitive portrayal of human emotion. He successfully bridged the worlds of academic art and popular appeal, creating images that resonated with his contemporaries and still offer valuable insights into the artistic and intellectual climate of nineteenth-century Scotland. His contribution to portraiture, historical painting, and the broader Scottish school ensures his place as a significant figure in British art history. His dedication to both his artistic practice and his scholarly interests marks him as a man of considerable depth and enduring influence.