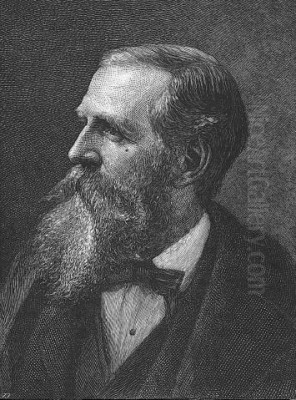

Robert Swain Gifford (1840-1905) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. A painter and etcher of considerable renown, Gifford captured the nuanced beauty of the American East Coast, particularly New England, as well as the exotic allure of distant lands. His career spanned a period of dynamic change in American art, and he navigated these shifts with a distinctive vision, blending meticulous observation with a poetic sensibility. Influenced by prevailing artistic currents yet forging his own path, Gifford left behind a body of work that continues to resonate with its quiet power and atmospheric depth.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on Nonamesset Island, Massachusetts, in 1840, Robert Swain Gifford's early life was steeped in the maritime environment of New England. This coastal upbringing would profoundly inform his artistic vision, instilling in him a deep appreciation for the subtle interplay of light, water, and land. His artistic talents emerged early, and a pivotal moment came around the age of seventeen when he encountered Albert Van Beest, a Dutch marine painter who had settled in New Bedford. Van Beest recognized Gifford's nascent abilities and took him under his wing, providing foundational training.

Though Gifford was largely self-taught, this early mentorship with Van Beest was crucial. He honed his skills in drawing and painting, initially focusing on marine subjects, a natural extension of his environment and Van Beest's influence. He later studied in Newburyport before moving to Boston, a burgeoning artistic center. By 1864, Gifford had established his own studio in New York City, placing himself at the heart of the American art world. This move marked his commitment to a professional artistic career and provided him access to a vibrant community of artists and patrons.

The Hudson River School's Enduring Legacy

Upon establishing himself in New York, Gifford's work naturally engaged with the dominant artistic movement of the time: the Hudson River School. This group of painters, including seminal figures like Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, and Frederic Edwin Church, sought to capture the grandeur and spiritual essence of the American wilderness. They celebrated the unique character of the American landscape, from the Catskill Mountains to the White Mountains of New Hampshire, often imbuing their scenes with a sense of awe and divine presence.

Gifford absorbed the Hudson River School's emphasis on detailed realism and a deep reverence for nature. His early landscapes, while perhaps not as overtly dramatic as some of Church's panoramic vistas or Albert Bierstadt's depictions of the American West, shared a commitment to faithful representation. He was a contemporary of the second generation of Hudson River School painters, such as Sanford Robinson Gifford (no relation), John Frederick Kensett, and Jasper Francis Cropsey, who often explored more intimate and atmospheric aspects of the landscape.

The Rise of Luminism and Atmospheric Concerns

Closely related to the Hudson River School, and a significant influence on Gifford, was the style known as Luminism. Luminist painters, including Fitz Henry Lane, Martin Johnson Heade, and the aforementioned Kensett and Sanford Robinson Gifford, were particularly concerned with the effects of light and atmosphere. Their works often feature calm, reflective waters, hazy skies, and a palpable sense of stillness, rendered with smooth, almost invisible brushwork. The emphasis was on capturing a specific moment, a particular quality of light, often at dawn or dusk.

Robert Swain Gifford's paintings, especially those of the New England coast, demonstrate a strong affinity with Luminist principles. He masterfully depicted the soft, diffused light of coastal regions, the subtle gradations of color in the sky and water, and the quiet solitude of marshes and shorelines. His palette, often characterized by low-toned ochres and greens, contributed to this atmospheric quality, creating scenes that were both realistic and deeply evocative.

The Barbizon Influence and the Shift Towards Tonalism

As the nineteenth century progressed, American artists increasingly looked to Europe for inspiration, and the French Barbizon School became particularly influential. Painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, and Théodore Rousseau rejected the highly finished, academic style in favor of more intimate, subjective, and often moody depictions of rural landscapes and peasant life. They emphasized tonal harmony, subtle color palettes, and a sense of atmosphere over precise detail.

This Barbizon sensibility resonated with many American painters, leading to the development of Tonalism in the latter part of the century. Tonalist artists, such as George Inness, Dwight William Tryon, and Alexander Helwig Wyant, favored evocative, atmospheric scenes rendered in a limited range of muted colors. Robert Swain Gifford's work shows a clear engagement with these ideas. While maintaining a degree of realism, his later landscapes increasingly emphasized mood, atmosphere, and the poetic qualities of nature, aligning him with the broader Tonalist movement. His focus on subdued color harmonies and the emotional impact of a scene reflects this shift.

Travels Abroad: Expanding Artistic Horizons

Like many American artists of his generation, Gifford sought to broaden his artistic education and find new subject matter through travel. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, he journeyed to the American West, an experience that exposed him to vastly different landscapes than those of his native New England. These travels were followed by extensive trips to Europe, Egypt, and North Africa.

These journeys had a profound impact on his art. His experiences in Egypt and North Africa, in particular, introduced him to the "Orientalist" themes popular in European art, championed by artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme and Eugène Delacroix. Gifford produced numerous paintings and sketches depicting the landscapes, architecture, and daily life of these regions. Works such as "Ruins of the Parthenon" (1869) and scenes from Egypt showcase his ability to capture the unique light and character of these foreign lands, adding a new dimension to his oeuvre. These Orientalist works were well-received and contributed to his growing reputation.

Mastery in Etching: The American Etching Revival

Beyond his accomplishments in oil painting and watercolor, Robert Swain Gifford was a highly skilled and influential etcher. He played a significant role in the American Etching Revival, a movement that sought to elevate etching as a fine art form in its own right, rather than merely a reproductive medium. This revival was inspired by the work of European masters like Rembrandt and contemporary figures such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Sir Francis Seymour Haden in Britain.

Gifford was a founding member of the New York Etching Club in 1877, an organization dedicated to promoting the art of etching. His own etchings were praised for their technical skill, atmospheric qualities, and sensitive rendering of landscape. His work "Blakemoor" is often cited as one of the most influential American etchings of the nineteenth century, demonstrating his command of line, tone, and composition in this demanding medium. His involvement in the Etching Revival underscores his versatility and his commitment to exploring different avenues of artistic expression.

The Tile Club: Camaraderie and Creative Exploration

Gifford was also a founding member of the "Tile Club," an informal association of artists, writers, and architects active in New York from 1877 to 1887. This eclectic group, which included prominent figures such as Winslow Homer, William Merritt Chase, J. Alden Weir, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens (though primarily a sculptor), met regularly to socialize, discuss art, and decorate ceramic tiles – hence the club's name.

The Tile Club organized several sketching expeditions, often to picturesque locations along the East Coast, which provided opportunities for camaraderie and artistic cross-pollination. These excursions were lighthearted and convivial, but also productive, allowing members to explore new subjects and techniques in a supportive environment. Gifford's participation in the Tile Club highlights his engagement with the broader artistic community of his time and his willingness to experiment with different media and collaborative activities.

An Educator's Influence: The Cooper Union

Robert Swain Gifford's contributions to American art extended beyond his own creative output. He was also a dedicated and respected educator. From 1877 to 1896, he taught painting at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York City. The Cooper Union, founded by Peter Cooper, was a pioneering institution offering free education to working-class students, and its art school was highly regarded.

As an instructor, Gifford would have influenced a generation of aspiring artists, sharing his knowledge of technique, composition, and the principles of landscape painting. His long tenure at Cooper Union speaks to his commitment to art education and his desire to nurture new talent. This role as an educator further solidified his position as a significant figure in the New York art world.

Notable Works and Artistic Characteristics

Throughout his career, Robert Swain Gifford produced a substantial body of work, with several paintings achieving particular recognition. His early success was marked by "Pines of New England" (1876), which won a first prize medal at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. This award brought him national attention and helped to establish his reputation as a leading landscape painter.

Another of his most celebrated works is "A Gorge in the Mountains," now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This painting exemplifies his mature style, showcasing his ability to render dramatic natural scenery with both accuracy and a sense of poetic grandeur. The Metropolitan Museum of Art also holds other significant works by Gifford, including "Tivoli" and "Isola Bella in Lago Maggiore," reflecting his European travels. His "New England Coast" (1880) is a quintessential example of his mastery in capturing the specific atmosphere of his native region. His sketchbooks, such as the one held by the Harvard Art Museums, provide invaluable insights into his working methods and his travels.

Gifford's style is characterized by its subtle tonal harmonies, often employing a palette of muted greens, browns, and grays, accented by soft blues and ochres. He had a remarkable ability to capture the effects of light and atmosphere, whether the hazy sunlight of a coastal morning or the dramatic shadows of a mountain pass. His brushwork, while capable of conveying detail, often aimed for a more unified and evocative effect, particularly in his later, Tonalist-influenced works.

The Harriman Alaska Expedition

Towards the end of his career, in 1899, Gifford participated in the famous Harriman Alaska Expedition. Organized by railroad magnate Edward H. Harriman, this ambitious scientific and artistic voyage brought together leading scientists, naturalists, writers, and artists to explore and document the Alaskan coast. Gifford, along with fellow artist Frederick S. Dellenbaugh, was tasked with creating visual records of the landscapes encountered.

This expedition provided Gifford with new and dramatic subject matter. He produced numerous sketches and paintings of Alaska's glaciers, mountains, and coastal scenery, capturing the raw, untamed beauty of this remote region. These works represent an important late phase in his career, demonstrating his continued adventurous spirit and his ability to adapt his style to new and challenging environments. His contributions were published in the multi-volume report of the expedition, further disseminating his work.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Robert Swain Gifford was a consistent exhibitor throughout his career, ensuring his work was regularly seen by the public and his peers. He first exhibited at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York in 1864 and became an Associate Member in 1867, and a full Academician in 1878. He continued to exhibit there almost annually until near the end of his life.

Beyond the National Academy, he was a founding member of the Society of American Artists, an organization formed in 1877 by younger artists who felt the Academy was too conservative. He was also a member of the American Watercolor Society, the National Arts Club, and an honorary member of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers in London. His works were shown in major exhibitions across the United States and internationally, and they found their way into important public and private collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Robert Swain Gifford remained an active artist into his later years, continuing to paint and explore new subjects. He passed away in New York City in 1905, leaving behind a rich legacy as one of America's foremost landscape painters and etchers of the nineteenth century.

His art reflects the major artistic currents of his time, from the detailed naturalism of the Hudson River School and the atmospheric concerns of Luminism to the subjective poetry of the Barbizon School and Tonalism. He adeptly synthesized these influences into a personal style characterized by its sensitivity to light, mood, and the subtle beauties of the natural world. His depictions of the New England coast remain iconic, while his Orientalist scenes and Alaskan landscapes demonstrate his versatility and adventurous spirit. As an artist, etcher, and educator, Robert Swain Gifford made a lasting contribution to the fabric of American art, and his works continue to be admired for their quiet elegance and profound connection to place.