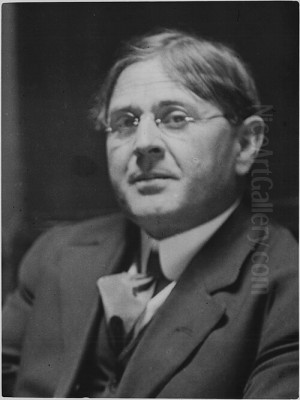

John William Beatty stands as a significant figure in the annals of Canadian art history. Born in Toronto, Ontario, on May 30, 1869, and passing away in the same city on October 4, 1941, Beatty dedicated his life to capturing the essence of the Canadian landscape and nurturing the talents of future generations. Primarily active within Canada, he was both a prolific painter and an influential art educator, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's cultural identity through his evocative depictions of its natural beauty, particularly the rugged wilderness of Northern Ontario.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Beatty's journey into the world of art began in his hometown of Toronto. He initially pursued practical training, working various jobs, including a stint as a firefighter. However, the call of art proved strong. He sought formal instruction, initially studying under local artists before enrolling at the Ontario School of Art and Design (now OCAD University). This foundational period provided him with the essential skills and discipline required for a career in painting. His early instructors likely included figures associated with the Toronto art scene of the late 19th century, a period marked by traditional approaches but also burgeoning interest in landscape.

Seeking to broaden his horizons and refine his technique, Beatty, like many aspiring North American artists of his time, looked towards Europe. Around the turn of the century, he traveled to Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world. There, he enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school known for attracting international students and offering a more liberal alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts. At Julian's, he studied under noted academic painters such as Jean-Paul Laurens and Benjamin Constant, absorbing the rigorous drawing and compositional principles emphasized in French academic training.

The Influence of Barbizon and Impressionism

While academic training provided a solid foundation, Beatty's artistic sensibilities were profoundly shaped by the prevailing movements outside the official Salon system. He was particularly drawn to the Barbizon School, a group of French painters active mid-century near the Forest of Fontainebleau. Artists like Jean-François Millet, Camille Corot, and Théodore Rousseau championed direct observation of nature, realistic depictions of rural life, and a focus on capturing atmospheric effects and the nuances of light. Beatty absorbed their tonal approach and their reverence for the landscape, qualities that would become hallmarks of his early Canadian work.

His time in Europe also exposed him to the revolutionary ideas of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, emphasized capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and colour through broken brushwork, and painting en plein air (outdoors). While Beatty never fully adopted a purely Impressionistic style, its influence is evident in the brightening of his palette and his increasing attention to the transient qualities of light and atmosphere in his later works. He skillfully blended the tonal subtlety of Barbizon with the chromatic vibrancy emerging from Impressionism.

Return to Canada: Forging a National Vision

Upon returning to Canada in the early 1900s, Beatty brought with him a wealth of European experience and a refined artistic vision. He settled back in Toronto but felt a strong pull towards depicting the unique character of his homeland. Around 1909, he made a conscious decision to focus on Canadian subjects, particularly the vast, untamed landscapes of Northern Ontario. This shift was more than just a change in subject matter; it was perceived by many as a patriotic act, an effort to define a distinctly Canadian art independent of European traditions.

His explorations took him deep into the wilderness, particularly to the region that would become Algonquin Provincial Park. He sought to capture the raw beauty, the dramatic skies, and the rugged spirit of the Canadian Shield. His paintings from this period often feature expansive views, dramatic cloud formations, and a powerful sense of solitude and grandeur. He employed the techniques learned abroad but adapted them to the specific light and character of the Canadian North.

The Evening Cloud of the Northland

One work, in particular, cemented Beatty's reputation and came to symbolize this new direction in Canadian art: The Evening Cloud of the Northland. Painted around 1910, this seminal piece depicts a vast, dramatic sky filled with towering cumulus clouds illuminated by the setting sun, reflected in the calm waters of a northern lake fringed by dark pines. The painting masterfully combines the tonal depth reminiscent of the Barbizon school with a heightened sensitivity to colour and light, capturing both the majesty and the subtle mood of the northern wilderness.

The significance of The Evening Cloud of the Northland was quickly recognized. In 1910 (though sometimes cited as 1911, the year it was likely formally accessioned or first prominently displayed there), it was purchased by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. This acquisition was a major milestone for Beatty and signaled growing institutional support for art that focused on Canadian themes rendered in a modern, yet accessible, style. The painting became an icon, celebrated for its powerful evocation of the northern landscape and considered by many to be Beatty's masterpiece. It represented a successful fusion of European technique and authentic Canadian feeling.

Algonquin Park and the Genesis of a Movement

Beatty's fascination with Northern Ontario, especially Algonquin Park, placed him at the heart of a burgeoning movement in Canadian landscape painting. He was one of the first artists to recognize the artistic potential of this rugged region, making numerous sketching trips there, often in challenging conditions. His early depictions of the park's lakes, forests, and dramatic weather paved the way for other artists who would soon follow.

He wasn't alone in these explorations for long. Beatty became a key figure among a group of like-minded Toronto artists who shared his passion for the Canadian wilderness. He undertook sketching expeditions to Algonquin Park with artists who would later form the core of the Group of Seven, including J.E.H. MacDonald and A.Y. Jackson. These trips were crucial for fostering camaraderie and exchanging ideas about how best to capture the unique spirit of the Canadian landscape. Beatty's experience and slightly more established position often made him a natural leader or mentor figure on these early excursions.

Friendship with Tom Thomson

Among Beatty's closest associates during this formative period was Tom Thomson. Thomson, a brilliant and innovative painter whose life was tragically cut short, shared Beatty's deep love for Algonquin Park. Beatty recognized Thomson's immense talent and played a supportive role in his development. A tangible example of their connection occurred in 1915 when Beatty, along with Dr. James MacCallum, a patron of the arts, helped finance and build a small studio or shack for Thomson on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. This provided Thomson with a dedicated space to work during his extended stays in the wilderness.

Their friendship extended beyond practical support. They shared sketching trips and undoubtedly discussed their artistic approaches to the northern landscape. When Thomson drowned mysteriously in Canoe Lake in the summer of 1917, Beatty was deeply affected. Along with J.E.H. MacDonald and Dr. MacCallum, Beatty was instrumental in erecting a memorial cairn to Thomson at Canoe Lake the following year, a lasting tribute to his friend and fellow artist who had become synonymous with the spirit of Algonquin Park.

Connection to the Group of Seven

While John William Beatty shared artistic goals and close personal ties with the artists who would officially form the Group of Seven in 1920, his exact relationship with the group is nuanced. He was older than most members and had established his reputation slightly earlier. His style, while progressive for its time and influential, remained perhaps more rooted in Barbizon and Impressionist traditions compared to the bolder colours and more stylized forms adopted by some Group members like Lawren Harris or Franklin Carmichael later on.

Beatty is best understood as a crucial precursor and influential mentor figure to the Group of Seven, rather than a formal member. He participated in early sketching trips, shared their enthusiasm for the North, and exhibited alongside them in various society shows. His painting The Evening Cloud of the Northland is often cited as a pivotal work that inspired the younger artists. He traveled extensively, not just in Ontario but also further afield. In 1914, for instance, he journeyed to the Canadian Rockies with A.Y. Jackson, exploring new landscapes that would also become important subjects for the Group. His pioneering efforts helped create the artistic climate in which the Group of Seven could flourish. Other members of the Group he associated with included Arthur Lismer and F.H. Varley.

War Artist: Documenting Conflict

The outbreak of the First World War brought a new, somber dimension to Beatty's career. In 1917, he was commissioned as an official war artist for the Canadian Expeditionary Force, under the auspices of the Canadian War Memorials Fund initiated by Lord Beaverbrook. This program aimed to create a comprehensive artistic record of Canada's involvement in the conflict.

From March to October 1918, Beatty served overseas in England and France. He witnessed firsthand the landscapes scarred by war and the realities faced by soldiers. His task was to translate these experiences into art. He produced numerous sketches and paintings depicting scenes behind the lines, training camps, and the devastated battlefields of the Western Front. Works from this period, such as Flanders Landscape or depictions of artillery positions, often carry a somber tone, reflecting the grim reality of modern warfare while still showcasing his skill in landscape composition and atmospheric rendering. This experience undoubtedly impacted him personally and artistically, adding another layer to his extensive body of work.

Educator and Mentor: Shaping Future Generations

Beyond his own painting, J.W. Beatty made a lasting contribution to Canadian art through his dedication to education. He joined the faculty of the Ontario College of Art (as it was then known) in 1912 and remained an influential instructor there until his death in 1941. He taught alongside other prominent Canadian artists like George Agnew Reid and C.M. Manly. His long tenure meant he guided several generations of art students.

His commitment to education extended beyond the regular academic year. In 1913, Beatty founded and became the director of the OCA's Summer School, initially located at Port Hope on Lake Ontario, and later moving to various locations including Algonquin Park. He ran this summer program until 1935. The summer school provided intensive outdoor sketching and painting opportunities, directly reflecting Beatty's own belief in the importance of working from nature. Many aspiring artists and art teachers from across Ontario attended these sessions, absorbing Beatty's methods and passion for the Canadian landscape. Through the summer school, his influence on art education in the province became particularly widespread and profound.

Evolving Artistic Style

Throughout his long career, Beatty's artistic style evolved, though it always retained a strong connection to landscape and a sensitivity to light and atmosphere. His early works clearly show the impact of the Barbizon school, characterized by muted palettes, tonal harmony, and an emphasis on mood, often depicting pastoral scenes or the quiet grandeur of the forest interior. His European training ensured a solid technical foundation in drawing and composition.

Following his time in Paris and his increasing focus on the Canadian North, his palette generally brightened, influenced by Impressionism. While he rarely adopted the fully broken brushwork of the French Impressionists, his application of paint became looser, and his interest in capturing the specific effects of Canadian light – the crisp clarity of northern air, the dramatic colours of sunrise and sunset – became more pronounced. Works like Morning, Algonquin Park exemplify this phase, balancing realistic depiction with expressive colour and light.

In his later years, some critics observed a shift towards a more decorative quality in his work. His compositions sometimes became more simplified, and his colours could be even brighter and more stylized. However, he remained committed to landscape as his primary subject matter. He continued to travel and sketch, exploring different regions of Canada, including trips to the West Coast, always seeking new motifs to interpret through his experienced eye and skilled hand. His style remained distinct from the more radical stylizations of some later Group of Seven work but consistently conveyed a deep and abiding connection to the Canadian land.

Wider Artistic Circle and Context

J.W. Beatty operated within a vibrant and evolving Canadian art scene. In Toronto, he was an active member of the arts community. He belonged to organizations like the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA) and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA), exhibiting regularly in their annual shows. He was also a member of the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto, a gathering place for artists, writers, musicians, and architects, where lively discussions about aesthetics, nationalism, and the future of Canadian culture took place.

His contemporaries included not only the members of the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson but also other significant Canadian painters. Figures like Maurice Cullen and Clarence Gagnon were also exploring Canadian landscapes, often influenced by Impressionism, particularly in Quebec. Earlier landscape traditions were represented by artists like Homer Watson, whose work Beatty would have known. Horatio Walker depicted rural Quebec life with a style also indebted to Barbizon principles. Beatty's work should be seen within this broader context of Canadian artists striving to define a national identity through the depiction of their own environment, moving away from European subjects and, gradually, from purely European styles.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Legacy

John William Beatty achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. The purchase of The Evening Cloud of the Northland by the National Gallery of Canada in 1910 was a significant early endorsement. His work was included in major national exhibitions, such as those organized by the OSA and RCA, and also represented Canada internationally. He exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon and his work was featured in the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, England, in 1924, which showcased art from across the Commonwealth.

His legacy rests on several pillars. Firstly, his powerful and evocative paintings of the Canadian landscape, particularly Northern Ontario, helped shape the way Canadians saw their own country. Works like The Evening Cloud remain iconic images in Canadian art. Secondly, his role as a pioneer and mentor, particularly his influence on Tom Thomson and the artists who formed the Group of Seven, marks him as a key figure in the development of a distinctly Canadian school of landscape painting. Thirdly, his long and dedicated career as an educator at the Ontario College of Art and through its summer school had a profound impact on generations of artists and art teachers across the province.

J.W. Beatty died in Toronto in 1941 at the age of 72. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be admired for its technical skill, its sensitivity to atmosphere and light, and its heartfelt portrayal of the Canadian wilderness. His paintings are held in major public collections across Canada, including the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and numerous regional museums, ensuring his contribution to Canadian art history is remembered and appreciated. He remains a respected figure, a bridge between 19th-century traditions and the bold new visions of 20th-century Canadian art.