Robert William Vonnoh stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the narrative of American art. A pivotal painter and an influential educator, Vonnoh was instrumental in introducing and popularizing Impressionist aesthetics in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His canvases, celebrated for their vibrant depiction of light, color, and atmosphere, particularly in landscapes and portraits, reflect a deep engagement with European artistic currents, which he skillfully adapted to an American context. Furthermore, his long tenure as an instructor at prestigious institutions like the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) allowed him to shape a generation of artists, many of whom would go on to define American art in the new century.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on September 17, 1858, in Hartford, Connecticut, Robert William Vonnoh's early life set the stage for a career dedicated to the arts. His family later relocated to Boston, a burgeoning cultural hub, where young Vonnoh's artistic inclinations found fertile ground. He embarked on his formal artistic training at the Massachusetts Normal Art School (now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design). This institution, founded to provide drawing teachers for public schools and to train professional artists, designers, and architects, offered Vonnoh a solid foundation in academic principles.

During his time at the Massachusetts Normal Art School, Vonnoh would have been exposed to traditional methods of drawing and painting, emphasizing draftsmanship and a faithful representation of subject matter. This early training, though conventional, was crucial in honing the technical skills that would later allow him to explore more avant-garde styles with confidence. Even at this stage, his talent was evident, and he soon transitioned from student to instructor at the same institution, teaching from 1879 to 1881. This early foray into teaching foreshadowed the significant role he would later play as an arts educator.

Parisian Sojourn and Impressionist Immersion

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Vonnoh recognized the necessity of further study in Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. In 1880, he made his first trip to France, enrolling at the prestigious Académie Julian. This private art school was a popular choice for international students, including many Americans, as it offered a more liberal alternative to the rigid École des Beaux-Arts and notably accepted female students. At the Académie Julian, Vonnoh studied under renowned academic painters Gustave Boulanger and Jules Joseph Lefebvre.

While Boulanger and Lefebvre were masters of the academic tradition, emphasizing historical subjects, meticulous finish, and idealized forms, Paris was simultaneously a hotbed of revolutionary artistic ideas. The Impressionist movement, which had held its first controversial exhibition in 1874, was challenging the very foundations of academic art. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas were championing painting en plein air (outdoors), capturing fleeting moments, and using broken brushwork with pure, unmixed colors to convey the transient effects of light and atmosphere.

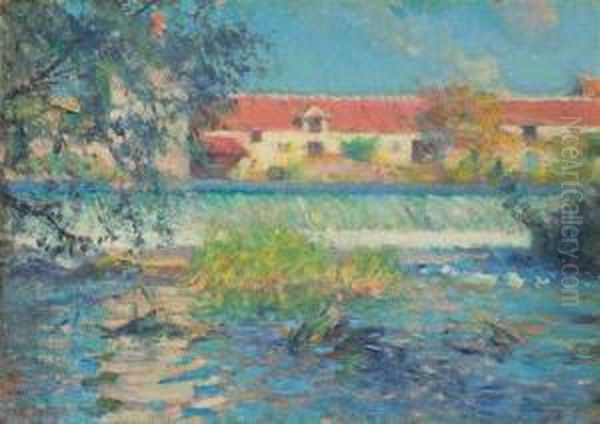

Vonnoh was profoundly influenced by these developments. He spent considerable time in the French countryside, particularly in Grez-sur-Loing, an artists' colony frequented by international painters, including Irish artist Roderick O'Conor and American artists such as Theodore Robinson, who was also deeply engaged with Monet's work. It was in these rural settings, immersed in the direct observation of nature, that Vonnoh began to experiment earnestly with Impressionist techniques. He embraced a brighter palette, looser brushwork, and a focus on capturing the sensory experience of a scene rather than a mere topographical record. His encounters with the work of Monet, in particular, left an indelible mark on his evolving style.

Return to America: A New Vision

Upon his return to the United States in 1883, Vonnoh brought with him the fresh perspectives and techniques he had absorbed in France. He resumed his teaching career, initially at the Cowles Art School in Boston in 1883, and then at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, starting in 1884. In these roles, he began to disseminate the principles of Impressionism to his American students, encouraging them to experiment with color, light, and direct painting from nature.

This period was crucial for the development of American Impressionism. While artists like Mary Cassatt and John Singer Sargent had already been working in an Impressionistic vein abroad, Vonnoh was among the first to actively teach and practice this style on American soil. He faced a public and critical establishment that was often conservative and slow to accept European modernism. However, his conviction in the expressive power of Impressionism, coupled with his skill as a painter, gradually began to win adherents.

His own work from this period demonstrates a growing mastery of the Impressionist idiom. He painted landscapes, garden scenes, and portraits that shimmered with light and color. He was particularly adept at capturing the nuances of atmospheric conditions and the play of sunlight on various surfaces. His approach was not a slavish imitation of French models but rather an adaptation of Impressionist principles to American subjects and sensibilities.

The Educator: Shaping a Generation at PAFA

Vonnoh's most significant impact as an educator arguably came during his tenure at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, where he began teaching in 1891. PAFA was, and remains, one of the most important art institutions in the United States, with a rich history of training influential artists. Vonnoh was appointed to teach portrait and figure painting, and his classes quickly became a magnet for progressive young students eager to break free from staid academic conventions.

At PAFA, Vonnoh's teaching emphasized direct observation, the importance of light and color in constructing form, and the expressive potential of brushwork. He encouraged his students to paint outdoors and to develop their individual artistic voices. His influence was profound, and he nurtured a remarkable group of talents who would go on to play major roles in the development of American art.

Among his most notable students at PAFA were Robert Henri and William Glackens. Henri would become the charismatic leader of "The Eight" and the Ashcan School, a group that, while moving towards a grittier urban realism, retained an appreciation for vigorous brushwork and directness of expression that owed a debt to Impressionist foundations. Glackens, also a member of The Eight, developed a more overtly Impressionistic style, often compared to Renoir, and became known for his vibrant depictions of modern life.

Other prominent artists who studied with Vonnoh or were influenced by his presence at PAFA include Walter Elmer Schofield and Edward Willis Redfield, who became leading figures of the New Hope School of American Impressionism, known for their robust, snow-covered Pennsylvania landscapes. Maxfield Parrish, celebrated for his distinctive illustrations and paintings with their luminous "Parrish blue," also passed through PAFA during Vonnoh's era. John Sloan, another key member of The Eight, also studied at PAFA, absorbing the changing artistic currents. Vonnoh's impact extended beyond just these names, as he fostered an environment of experimentation and openness to new ideas.

Vonnoh's Artistic Style and Techniques

Robert Vonnoh's artistic style is firmly rooted in Impressionism, yet it possesses distinctive characteristics that reflect his individual sensibility and American context. He was particularly renowned for his landscapes and portraits, demonstrating a versatile command of the Impressionist vocabulary across different genres.

A hallmark of Vonnoh's technique was his sophisticated use of color. He employed a bright, high-keyed palette, often applying paint in small, distinct dabs or strokes – the "broken color" technique characteristic of Impressionism. This method allowed colors to mix optically in the viewer's eye, creating a sense of vibrancy and luminosity. He was particularly attuned to the subtle shifts in color caused by changing light and atmospheric conditions, a skill evident in his depictions of gardens, fields, and sun-dappled portraits. His landscapes often feature cool color palettes, balanced compositions, and an emphasis on capturing the overall mood or atmosphere of a scene.

Light was a central preoccupation for Vonnoh, as it was for all Impressionists. He masterfully rendered the effects of sunlight and shadow, using them not merely to define form but to create visual excitement and emotional resonance. Whether depicting the bright sunshine of a summer field or the more diffused light of an interior, his paintings convey a strong sense of specific lighting conditions.

His brushwork was typically energetic and visible, contributing to the dynamism of his surfaces. While capable of more finished passages, especially in commissioned portraits, he often favored a looser, more gestural application of paint that conveyed a sense of immediacy and spontaneity. This expressive brushwork, combined with his vibrant color, gave his paintings a lively, tactile quality. In some works, particularly his poppy field paintings, the impasto is quite thick, giving the paint an almost sculptural, bas-relief quality.

While deeply influenced by French masters like Monet, Vonnoh's Impressionism was not merely derivative. He adapted the style to American landscapes and subjects, often imbuing his work with a distinctly American sensibility. His portraits, for instance, while employing Impressionist techniques, also retained a strong sense of character and psychological insight, aligning with the American portrait tradition.

Signature Works and Critical Reception

Among Robert Vonnoh's most celebrated and representative works is "In Flanders Field" (also known as "Poppies" or "Coquelicots"), painted in 1890 during his time in France. This iconic painting depicts a young woman, often identified as his future (second) wife, the sculptor Bessie Potter, standing in a vibrant field of red poppies under a bright summer sky. The canvas explodes with color, the brilliant reds of the flowers contrasting with the greens of the foliage and the blues of the sky, all rendered with energetic, textured brushstrokes. The painting is a quintessential example of Vonnoh's Impressionist style, capturing the dazzling effect of sunlight on a landscape teeming with life.

It is important to note that Vonnoh's painting predates John McCrae's famous WWI poem "In Flanders Fields" by over two decades. The title "In Flanders Field" or variations like "Where Soldiers Sleep and Poppies Grow" were likely applied or popularized later, perhaps due to the evocative imagery shared with the poem. The Butler Institute of American Art, which acquired the painting in 1919 through its founder Joseph G. Butler Jr., lists it as "In Flanders Field (Where Soldiers Sleep and Poppies Grow) Coquelicots." The work received considerable acclaim when exhibited, though its bold use of color and thick impasto also drew criticism from more conservative quarters. Some critics at the 1892 Munich exhibition, for instance, reportedly found the paint application so heavy as to resemble "oil paint in bas-relief."

Another version of this subject, sometimes titled "Poppy Field (In Flanders Field)" or simply "Poppies," painted around 1888, showcases a similar theme with a slightly different composition, emphasizing his sustained interest in the motif. These poppy paintings are perhaps his best-known works and are considered landmarks of American Impressionism.

Vonnoh was also a respected portraitist. His portraits, such as that of his student Joseph T. Pearson, Jr. (c. 1915-1916), demonstrate his ability to combine Impressionist techniques with a keen sense of likeness and character. He painted numerous prominent individuals, and his portraits were generally well-received for their freshness and vitality.

Throughout his career, Vonnoh exhibited widely, both in the United States and Europe. He showed work at the Paris Salon, the National Academy of Design in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and various international expositions, winning several awards and medals. His work gradually gained acceptance and was acquired by major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Personal Life and Artistic Connections

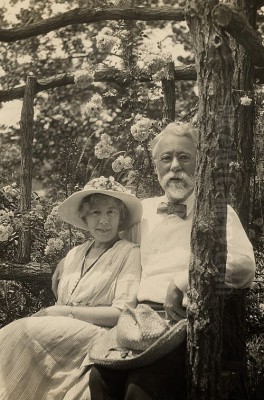

Robert Vonnoh's personal life was intertwined with his artistic career. He was married twice, both times to fellow artists. His first wife was Grace D. Farrell, whom he married in 1886. She passed away in the late 1890s.

In 1899, Vonnoh married Bessie Onahotema Potter (1872–1955), a talented and successful sculptor who became known as Bessie Potter Vonnoh. She was considerably younger than him and had been one of his students at the Art Institute of Chicago (though he is more famously associated with PAFA, he did teach elsewhere). Bessie Potter Vonnoh specialized in small, intimate bronze sculptures, often depicting women and children in everyday domestic scenes, rendered with a graceful, Impressionistic touch. Her work complemented her husband's paintings, and they formed an artistic partnership, often exhibiting together and supporting each other's careers. They established a summer home and studio in Old Lyme, Connecticut, which had become a prominent center for American Impressionism, attracting artists like Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, and Frank DuMond.

Vonnoh maintained connections with many leading artists of his day. His time in France brought him into contact with figures like Roderick O'Conor. In America, his role as an educator and his involvement in various art societies placed him at the center of a vibrant artistic community. He was an associate member of the National Academy of Design from 1900 and a full academician from 1906. He was also a member of the Society of American Artists, a group that had broken away from the more conservative National Academy to promote newer artistic styles.

His students, such as Robert Henri, William Glackens, John Sloan, Edward Redfield, and Walter Elmer Schofield, went on to form their own circles and movements, but the foundational influence of Vonnoh's teaching, particularly his emphasis on Impressionist principles and direct painting, remained a significant part of their artistic DNA. The camaraderie and sometimes rivalries among these artists, and with other contemporaries like William Merritt Chase (another influential teacher of Impressionism), Edmund Tarbell, Frank W. Benson (key figures of the Boston School), and J. Alden Weir, characterized the dynamic American art scene of the period.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In the early 20th century, as new artistic movements like Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism began to emerge and gain traction, Impressionism gradually became a more established, historical style rather than a cutting-edge avant-garde movement. Vonnoh continued to paint and teach, adapting his style somewhat over the years but remaining largely faithful to the Impressionist principles he had championed.

He spent his later years dividing his time between the United States and France. He maintained a studio in New York and his summer home in Old Lyme, Connecticut, but also frequently traveled to France, particularly to Grez-sur-Loing, which held a special significance for him, and later to Nice on the French Riviera.

Unfortunately, Vonnoh's later career was hampered by failing eyesight, a cruel affliction for a painter so attuned to the visual nuances of light and color. Despite this challenge, he continued to work as much as his health permitted. Robert William Vonnoh passed away in Nice, France, on December 28, 1933, at the age of 75. His wife, Bessie Potter Vonnoh, outlived him by more than two decades, continuing her own successful career as a sculptor.

Robert Vonnoh's legacy is twofold. Firstly, as a painter, he created a significant body of work that stands as a testament to the vitality of American Impressionism. His landscapes and portraits are admired for their beauty, technical skill, and expressive power. Works like "In Flanders Field" remain iconic images of the era.

Secondly, and perhaps equally importantly, his legacy as an educator is profound. Through his teaching at the Massachusetts Normal Art School, the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and most notably at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, he influenced a generation of American artists. He played a crucial role in disseminating Impressionist ideas and techniques in the United States, helping to modernize American art and pave the way for subsequent developments. His students, including key figures of The Eight and the New Hope School, carried forward his emphasis on direct observation, vibrant color, and expressive brushwork, even as they forged their own distinct artistic paths.

Vonnoh in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Robert Vonnoh's contribution, it is essential to view him within the broader context of American and European art at the turn of the 20th century. He was part of a wave of American artists who sought training in Europe, particularly Paris, and returned to the United States eager to apply modern European styles to American subjects.

In France, he was a contemporary of the second generation of Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. While directly influenced by masters like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, he also would have been aware of the emerging talents of artists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin (whose work with Roderick O'Conor in Pont-Aven was influential), and Georges Seurat.

In the United States, Vonnoh was a key figure among the first generation of American Impressionists. He worked alongside and often taught artists who became leading exponents of the style, such as Childe Hassam, whose depictions of flag-draped New York streets and New England gardens are iconic; John Henry Twachtman, known for his ethereal, Tonalist-inflected Impressionist landscapes; J. Alden Weir, whose work often blended Impressionism with a more traditional American sensibility; and Theodore Robinson, who was a close associate of Monet in Giverny.

As an educator, Vonnoh's influence can be compared to that of William Merritt Chase, another pivotal figure in American Impressionism who taught at the Art Students League of New York and founded the Chase School of Art (later Parsons School of Design). Both Vonnoh and Chase were instrumental in training young artists in Impressionist techniques and fostering a more modern outlook in American art.

The students Vonnoh nurtured at PAFA, particularly Robert Henri, William Glackens, and John Sloan, went on to challenge the genteel tradition often associated with American Impressionism. As leaders of The Eight and the Ashcan School, they turned their attention to the grittier realities of urban life, yet their painterly approach, emphasis on capturing immediate impressions, and often vibrant palettes owed a debt to the Impressionist foundations Vonnoh had helped lay. Thus, Vonnoh's influence extended beyond Impressionism itself, contributing to the broader currents of American modernism.

Conclusion

Robert William Vonnoh was a vital force in American art during a period of significant transformation. As a painter, he created luminous and expressive works that beautifully captured the American landscape and its people through an Impressionist lens. His ability to absorb European innovations and adapt them into a distinctly American visual language marks him as a significant artist of his time.

Beyond his own artistic production, Vonnoh's role as an educator was paramount. He was a dedicated and inspiring teacher who equipped a new generation of American artists with the tools and perspectives of modernism. His legacy lives on not only in his own canvases but also in the work of the many students he mentored, who in turn helped to shape the course of 20th-century American art. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his French Impressionist counterparts or even some of his own students, Robert William Vonnoh's contributions as both a practitioner and a proponent of Impressionism in America secure his place as a key figure in the history of American art.