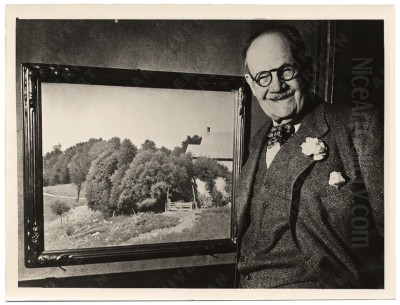

Frank Vincent DuMond (1865-1951) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of American art. His dual legacy as both a celebrated painter, particularly within the Impressionist movement, and an extraordinarily influential art educator who shaped generations of American artists, cements his place in art history. His long career spanned a period of dramatic change in the art world, yet he remained a steadfast proponent of foundational skills, keen observation, and the expressive power of color and light.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Rochester, New York, on August 20, 1865, Frank Vincent DuMond demonstrated an early aptitude for art. His formative years were spent in a city that, while not a major art center like New York or Boston, provided a supportive environment for his burgeoning talent. His family, recognizing his artistic inclinations, encouraged his pursuits. This early support was crucial, allowing him to develop his skills through local instruction and self-study before seeking more formal training.

Even as a young man, DuMond was known for his diligence and keen eye. He initially worked as an illustrator for local publications, a common starting point for many artists of his era. This work, while commercial, honed his drafting skills and his ability to capture character and narrative, qualities that would subtly inform his later easel painting. The demands of illustration, requiring quick observation and effective composition, provided a practical foundation that complemented his later, more academic, artistic education.

Academic Foundations and Parisian Sojourn

The lure of more advanced art training eventually led DuMond to New York City, the burgeoning heart of the American art scene. In 1884, he enrolled at the prestigious Art Students League of New York. This institution, founded by students who had seceded from the National Academy of Design in search of a more progressive and European-style education, was a crucible for aspiring American artists. At the League, DuMond studied under notable figures such as Carroll Beckwith and William Sartain, artists who themselves had experienced European training and brought those methods back to the United States.

DuMond's talent quickly became apparent. By 1888, his ambition and the prevailing artistic current directed him, like so many of his contemporaries, to Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe, including many Americans. In Paris, he received rigorous academic training under the tutelage of influential masters such as Gustave Boulanger, Jules Joseph Lefebvre, and Benjamin Constant. These instructors were stalwarts of the French academic tradition, emphasizing precise drawing, anatomical accuracy, and the careful modeling of form.

During his time in Paris, which extended until 1891, DuMond absorbed not only the academic principles but also the vibrant artistic atmosphere of the city. He exhibited at the Paris Salon, a significant achievement for any young artist, receiving honorable mention for his painting "The Holy Family" in 1890. This work, a religious scene rendered with academic polish and a sensitive portrayal of its subjects, demonstrated his mastery of the traditional techniques he had learned. While in Paris, he also encountered the burgeoning Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements, though his own work at this stage remained more closely aligned with academic realism.

Return to America and a Flourishing Painting Career

Upon his return to the United States, DuMond initially continued to work in a style that reflected his Parisian academic training, often focusing on figurative and religious subjects. He also engaged in illustration work for prominent magazines like Harper's Monthly Magazine and Century Magazine, which provided financial stability and kept his work visible to a wide audience. His illustrations were noted for their draftsmanship and narrative clarity.

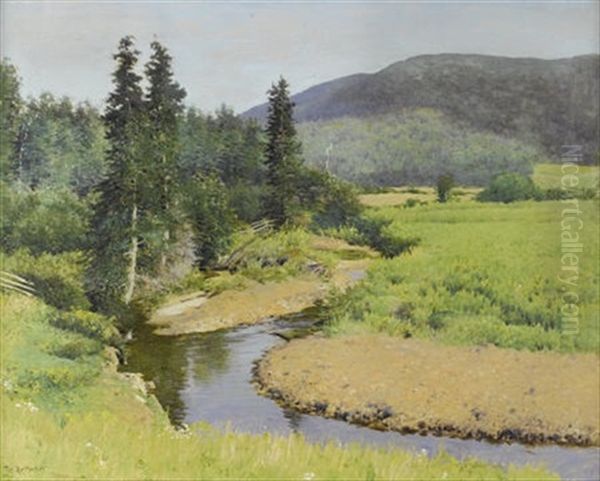

However, the influence of Impressionism, which he had witnessed firsthand in France and which was gaining traction in America, began to permeate his work. He started to explore the effects of light and atmosphere, gradually lightening his palette and loosening his brushwork. This transition was not abrupt but rather a thoughtful integration of Impressionist principles with his strong academic grounding. He became particularly known for his landscapes, which captured the nuanced beauty of the American countryside.

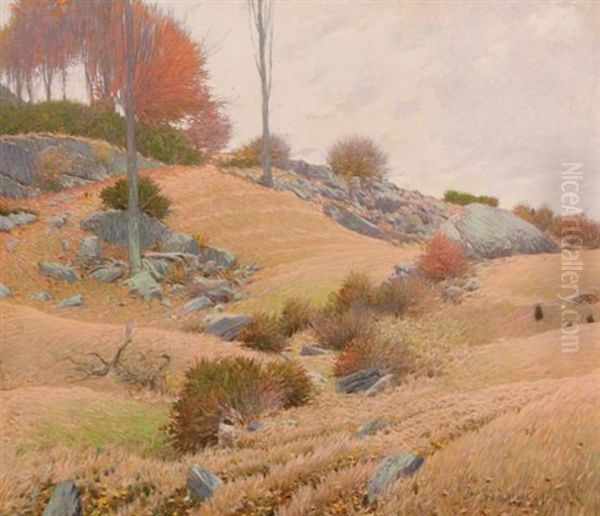

DuMond's paintings from this period often depict serene, light-filled scenes. He was adept at conveying the subtle shifts in color and light at different times of day and in varying weather conditions. His landscapes are characterized by a harmonious balance of color, a sophisticated understanding of atmospheric perspective, and a poetic sensibility. He was not merely transcribing nature but interpreting its moods and effects.

The Old Lyme Art Colony and American Impressionism

A pivotal chapter in DuMond's artistic development and his association with American Impressionism was his involvement with the Old Lyme Art Colony in Connecticut. Founded by artist Henry Ward Ranger around 1900, Old Lyme became one of the most important centers of American Impressionism. Attracted by the picturesque landscape and the collegial atmosphere, DuMond began spending summers there in 1902, eventually establishing a home and studio.

At Old Lyme, DuMond worked alongside other prominent American Impressionists, including Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, and J. Alden Weir. This community of artists fostered a vibrant exchange of ideas and techniques. The influence of the colony is evident in DuMond's work from this period, which often features the sun-dappled fields, gentle hills, and reflective waters of the Connecticut landscape. His paintings became increasingly luminous and imbued with a sense of tranquility and harmony with nature. Works like "A Monhegan Afternoon" and "Grassy Hill" exemplify his mature Impressionist style, showcasing his mastery of color and light to evoke a specific time and place.

DuMond's approach to Impressionism was often described as more tonal than that of some of his more purely Impressionist colleagues. While he embraced the broken brushwork and bright palette characteristic of the movement, he also retained a strong sense of underlying structure and a subtle modulation of tones, perhaps a lingering influence of his academic training and an appreciation for artists like James McNeill Whistler or the Barbizon School painters such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.

A Storied Teaching Career at the Art Students League

While DuMond achieved considerable success as a painter, his most enduring legacy is arguably his profound impact as an art educator. In 1892, shortly after his return from Paris, he began teaching at the Art Students League of New York, an association that would last for nearly sixty years, until his death in 1951. This remarkable tenure makes him one of the longest-serving and most influential instructors in the League's history.

DuMond's teaching philosophy was rooted in a deep understanding of artistic principles combined with a nurturing approach that encouraged individual expression. He emphasized the importance of draftsmanship, composition, and, most famously, color theory. He believed that a thorough understanding of the fundamentals was essential before an artist could truly find their own voice. His classes were immensely popular, attracting a diverse range of students who would go on to become some of America's most celebrated artists.

He was known for his articulate lectures and his ability to demystify complex artistic concepts. His critiques were insightful and constructive, aimed at helping students develop their critical eye and technical skills. He fostered an environment of serious study and artistic exploration, inspiring loyalty and admiration among his pupils.

The Prismatic Palette and Color Theory

One of DuMond's most significant contributions to art education was his development and teaching of the "prismatic palette." This systematic approach to color mixing was designed to help students understand the relationships between colors and to achieve luminous, harmonious effects in their paintings. The prismatic palette involved pre-mixing a series of color gradations, moving from warm to cool, which could then be used to depict the effects of light and shadow with greater accuracy and vibrancy.

DuMond taught that light was the source of all color and that by understanding how light behaves, artists could create more convincing and expressive representations of the world. His palette system was not a rigid formula but rather a tool to help students see and interpret color more effectively. He encouraged them to observe nature closely and to use the palette as a guide for translating their observations onto canvas. Many of his students attested to the transformative impact of his color theories on their work, enabling them to achieve a new level of richness and luminosity. This methodical approach to color was particularly influential for landscape painters seeking to capture the fleeting effects of natural light.

Notable Students and Lasting Influence

The list of artists who studied with Frank Vincent DuMond at the Art Students League reads like a who's who of 20th-century American art. His students included such diverse and influential figures as Georgia O'Keeffe, Norman Rockwell, John Marin, Charles Webster Hawthorne, Eugene Speicher, Frank Mason, Everett Raymond Kinstler, Ogden Pleissner, Kenneth Hayes Miller, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Each of these artists, while developing their own distinct styles, carried with them aspects of DuMond's teachings, whether it was his emphasis on strong composition, his understanding of color, or his disciplined approach to art-making.

Georgia O'Keeffe, for instance, though she later diverged significantly from DuMond's Impressionistic style, credited him with providing her with a solid technical foundation. Norman Rockwell, the iconic American illustrator, benefited from DuMond's instruction in figurative drawing and narrative composition. John Marin, a leading American modernist, absorbed DuMond's lessons on light and color, which he later adapted to his own expressive and dynamic style. Charles Webster Hawthorne, another influential teacher, founded the Cape Cod School of Art and propagated his own version of Impressionist principles, likely informed by his studies with DuMond.

The sheer number and caliber of his students testify to DuMond's effectiveness as an educator. He did not seek to create disciples who mimicked his own style but rather to equip artists with the tools and understanding they needed to pursue their own artistic visions. His influence extended far beyond the classroom, as his students, in turn, often became teachers themselves, further disseminating his principles.

Key Works and Artistic Themes

Throughout his long career, DuMond produced a substantial body of work. While his early painting "The Holy Family" (1890) garnered acclaim and demonstrated his academic prowess, his reputation largely rests on his Impressionist landscapes. These works, often painted en plein air or developed from outdoor sketches, capture the beauty and tranquility of the American countryside, particularly New England.

Representative landscape titles include "Sunny Pastures," "October Haze," "The Marshes of Old Lyme," and "Connecticut Hills." These paintings are characterized by their luminous color, atmospheric depth, and harmonious compositions. DuMond had a particular skill for depicting the subtle gradations of light and color in skies and water, and the interplay of sunlight and shadow on foliage and terrain. His brushwork, while often loose and suggestive in the Impressionist manner, always maintained a sense of control and purpose.

Beyond landscapes, DuMond also painted portraits and figurative works throughout his career. His portraits, while perhaps less well-known than his landscapes, demonstrate his strong drafting skills and his ability to capture the personality of his sitters. He also undertook mural commissions, including work for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, showcasing his versatility and his ability to work on a large scale.

Affiliations and Artistic Communities

Frank Vincent DuMond was an active participant in the artistic communities of his time. His long association with the Art Students League of New York was central to his career, not only as an instructor but also as a respected member of its community. He was also deeply involved with the Old Lyme Art Colony, where he was a leading figure and helped to shape its artistic identity. He served as president of the Lyme Art Association, which grew out of the colony.

DuMond was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1900 and a full Academician in 1906, prestigious honors that recognized his standing in the American art world. He was also a member of other prominent art organizations, including the Salmagundi Club in New York, one of the oldest art clubs in the United States. These affiliations provided him with platforms for exhibiting his work, opportunities for professional exchange, and a voice in the broader artistic discourse of the nation. His participation in these groups underscored his commitment to the professionalization and advancement of American art.

Anecdotes and Personal Insights

DuMond was remembered by his students and colleagues not only for his artistic talent and teaching abilities but also for his character. He was often described as a kind, patient, and encouraging mentor, though he also maintained high standards and expected dedication from his students. One anecdote often recounted by his students pertains to his meticulous preparation of his prismatic palette. He would carefully mix and arrange his colors before each painting session, a practice that underscored his methodical approach to art.

Another story highlights his dedication to teaching. Even in his later years, when his health was failing, he continued to teach with passion and commitment. He would often hold court in the Art Students League's communal spaces, engaging students in discussions about art and life, always generous with his time and knowledge. His commitment to his students was legendary, and many maintained lifelong correspondences with him, seeking his advice and sharing their artistic progress. He was also known for his love of nature, which was evident in his landscape paintings and his choice to live and work in places like Old Lyme.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

While direct artistic "collaborations" in the sense of co-authored paintings were not typical for DuMond, his career was rich with interactions and mutual influences among his contemporaries. His time in Paris alongside other aspiring American artists, and later his deep involvement in the Old Lyme Art Colony, provided fertile ground for such exchanges. At Old Lyme, artists like Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, J. Alden Weir, Walter Griffin, and Henry Ward Ranger shared a common pursuit of capturing the American landscape through an Impressionist lens. They painted similar subjects, critiqued each other's work, and undoubtedly learned from one another.

His teachers in Paris—Gustave Boulanger, Jules Joseph Lefebvre, and Benjamin Constant—were significant influences on his early development. Later, as a teacher himself, he engaged in a form of intellectual collaboration with his students, guiding them while also, perhaps, being stimulated by their fresh perspectives. His relationship with fellow instructors at the Art Students League, such as William Merritt Chase (who also taught at the League for a period and was a leading American Impressionist) and Kenyon Cox (a proponent of academic classicism), would have involved ongoing dialogue about art and pedagogy, even if their artistic philosophies differed. The artistic environment of the early 20th century was one of dynamic exchange, and DuMond was an integral part of this network.

Artistic Evolution and Later Years

DuMond's artistic style, while firmly rooted in Impressionism from the early 1900s onward, did show subtle evolutions. While he never abandoned his commitment to representational art or his core principles of color and light, his later work sometimes exhibited a broader handling of paint and an even greater emphasis on atmospheric effects. He remained a prolific painter throughout his life, continually exploring the nuances of the landscapes he loved.

Even as new artistic movements like Modernism gained prominence, DuMond remained steadfast in his artistic convictions. He continued to champion the importance of skill, observation, and the pursuit of beauty in art. His teaching, too, remained consistent in its core principles, providing a stable anchor for students navigating a rapidly changing art world. He continued to teach at the Art Students League and to paint in Old Lyme until shortly before his death.

Enduring Influence and Legacy

Frank Vincent DuMond passed away in New York City on February 6, 1951, at the age of 85. His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he made significant contributions to American Impressionism, creating a body of work celebrated for its beauty, technical skill, and sensitive interpretation of the American landscape. His paintings are held in numerous museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme.

However, it is perhaps as an educator that his influence has been most profound and far-reaching. Through his nearly six decades of teaching at the Art Students League, he shaped the artistic development of thousands of students. His teachings on color theory, particularly the prismatic palette, continued to be passed down by his students and their students, creating an artistic lineage that extends to the present day. Artists like Frank Mason, one of DuMond's devoted pupils, became a prominent teacher himself at the League, carrying forward DuMond's principles for another generation.

DuMond's dedication to the fundamentals of art, combined with his ability to inspire individual creativity, made him a uniquely effective teacher. He provided a bridge between the academic traditions of the 19th century and the evolving artistic landscape of the 20th century, equipping his students with timeless skills that transcended stylistic trends. His life and work serve as a testament to the enduring power of art and the profound impact of a dedicated teacher. His contributions ensure his place as a key figure in the history of American art, both for the canvases he created and for the countless artists he inspired.