Salomon Koninck (1609-1656) stands as a significant, if sometimes overshadowed, figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Born and deceased in the bustling artistic hub of Amsterdam, Koninck's career unfolded during a period of unprecedented artistic flourishing in the Netherlands. He navigated a world populated by giants of art, absorbing influences, forging his own path, and leaving behind a body of work that continues to intrigue scholars and art lovers alike. His oeuvre, characterized by the prevailing Baroque style, encompasses evocative genre scenes, insightful portraits, and profound religious narratives, all rendered with a distinctive warmth and psychological depth.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Amsterdam

Salomon Koninck was born in Amsterdam in 1609, into a city that was rapidly becoming one of Europe's leading commercial and cultural centers. This vibrant environment provided fertile ground for artistic talent. His father was a goldsmith, an occupation that often had close ties with the visual arts through shared skills in design and craftsmanship. While details of his earliest training are somewhat sparse, it is widely accepted that he was a pupil of David Colyns. Colyns himself was a painter of historical and biblical subjects, and had connections to the pre-Rembrandt generation, potentially serving as an assistant to Pieter Lastman, who was famously one of Rembrandt's teachers.

This connection to Lastman, even if indirect through Colyns, is significant. Lastman was a pivotal figure in introducing a more dramatic, Italianate history painting style to Amsterdam, characterized by lively compositions, expressive figures, and rich colors. Koninck would have absorbed these foundational elements, learning the importance of narrative clarity and emotional expression in depicting historical and biblical scenes. His early development would have also been shaped by the broader artistic currents in Amsterdam, where demand for various genres of painting was high, from portraits catering to the wealthy merchant class to detailed genre scenes reflecting everyday life.

Further enriching his artistic education, Koninck is believed to have studied with François Venant and Claes Corneliszoon Moeyaert. Moeyaert, like Lastman, was a prominent history painter in Amsterdam before Rembrandt's rise, known for his biblical and mythological scenes. Exposure to these masters would have provided Koninck with a solid grounding in the techniques and thematic concerns prevalent in Dutch art of the early 17th century.

The Enduring Influence of Rembrandt

Perhaps the most defining artistic relationship in Salomon Koninck's career was with Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669). While the precise nature of their association – whether Koninck was a formal pupil in Rembrandt's workshop or an independent artist deeply influenced by the master – is still a subject of scholarly discussion, the stylistic parallels are undeniable. Koninck is often counted among the "Rembrandtists" or the "School of Rembrandt," a broad group of artists who adopted or were significantly impacted by Rembrandt's innovative approach to light, composition, and psychological portrayal.

Koninck's works frequently exhibit the dramatic chiaroscuro, the interplay of light and shadow, that became a hallmark of Rembrandt's style. He employed a warm, earthy color palette, favoring rich browns, deep reds, and golden ochres, which contributed to the intimate and often contemplative mood of his paintings. This is particularly evident in his depictions of scholars, philosophers, and elderly figures, subjects also favored by Rembrandt. The focused illumination on faces and hands, emerging from deeply shadowed backgrounds, served to heighten the emotional intensity and draw the viewer into the psychological space of the figures.

Thematic overlaps are also common. Koninck, like Rembrandt, often turned to Old Testament narratives, exploring their dramatic potential and human dimensions. His handling of these subjects, while sharing Rembrandt's gravitas, often possessed its own distinct character. The close stylistic resemblance has, over the centuries, led to numerous instances of Koninck's works being misattributed to Rembrandt, a testament to Koninck's skill in emulating the master's visual language, but also a factor that has sometimes complicated the assessment of his unique contributions.

One notable example often cited is Koninck's "Philosopher with a Classical Book," which has been considered a companion piece or a response to Rembrandt's "Meditating Philosopher." Both works explore themes of scholarship and introspection, utilizing similar lighting and compositional strategies, yet each retains the individual touch of its creator. This dialogue, whether direct or indirect, underscores the vibrant artistic exchange that characterized Amsterdam's art scene.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Salomon Koninck's artistic style is firmly rooted in the Baroque tradition, characterized by its dynamism, emotional intensity, and rich visual textures. He demonstrated a remarkable versatility, adeptly handling various subjects and imbuing them with a profound sense of humanity.

A key feature of his work is the warm tonality and the sophisticated use of light. His figures are often bathed in a soft, golden light that models their forms and creates a palpable atmosphere. This is not merely a technical device but serves to enhance the narrative and emotional content of his paintings. He was particularly skilled at rendering the textures of fabrics, the wrinkled skin of old age, and the gleam of metal or polished wood, adding a tactile quality to his compositions.

Philosophical and scholarly themes appear frequently in Koninck's oeuvre. He depicted wise old men, hermits, and alchemists engrossed in their studies or experiments, often surrounded by books, globes, and scientific instruments. These paintings reflect the intellectual curiosity of the Dutch Golden Age and the era's fascination with knowledge and discovery. Works like "Alchemist Cutting His Nails" (c. 1630-1650) delve into these esoteric pursuits, capturing both the meticulousness and the mystery associated with such figures.

Religious subjects, primarily drawn from the Old Testament, formed another significant part of his output. Paintings such as "Joseph Explaining Pharaoh's Dreams" showcase his ability to convey complex narratives with clarity and emotional depth. He focused on the human drama within these sacred stories, making them relatable and engaging for his contemporary audience. His treatment of these themes often emphasized moments of revelation, divine intervention, or profound human emotion, aligning with the Baroque sensibility for dramatic impact.

Portraiture: Capturing Character and Status

Portraiture was a cornerstone of Dutch Golden Age art, and Salomon Koninck made notable contributions to this genre. He painted portraits of individuals, often scholars or figures of dignified age, capturing not just their likeness but also a sense of their inner life and character. His portraits are typically characterized by their sensitive modeling, rich textures, and the expressive use of light to highlight the sitter's features and personality.

His "The Old Bishop" (1648) is a fine example of his skill in this area, portraying the subject with a blend of authority and gentle humanity. The meticulous rendering of the aged face, the textures of the vestments, and the thoughtful expression all contribute to a powerful and engaging image. Koninck's self-portraits, one of which is housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, offer a glimpse into how the artist saw himself, conforming to the tradition of artists presenting themselves with the attributes of their profession or as learned individuals.

Unlike the more flamboyant or overtly status-driven portraits by some of his contemporaries, such as Frans Hals (c. 1582/83–1666) with his dynamic brushwork, Koninck's portraits often possess a quieter, more introspective quality, aligning with the Rembrandtesque emphasis on psychological depth. He was adept at conveying the dignity and wisdom of age, a recurring theme in his work.

Genre Scenes: Reflections of Daily Life and Morality

While perhaps less prolific in genre painting than specialists like Jan Steen (c. 1626–1679) or Adriaen Brouwer (c. 1605/06–1638), Salomon Koninck did produce compelling scenes that commented on contemporary life and morality. His genre works often carried allegorical or symbolic meanings, a common feature in Dutch art of the period.

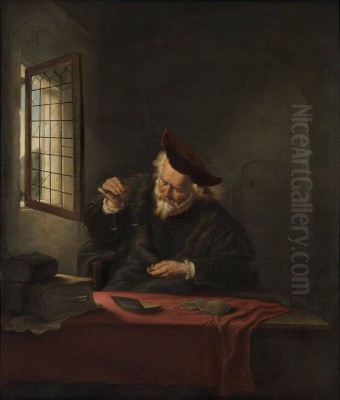

"The Gold-weigher" is a particularly well-known example, often interpreted as a commentary on avarice and the worldly pursuit of wealth. Such paintings served as visual sermons or moral lessons, encouraging viewers to reflect on virtues and vices. The detailed rendering of the setting, the objects, and the expressive figures in these scenes demonstrates Koninck's keen observational skills and his ability to weave narrative and meaning into everyday subjects. These works provide valuable insights into the social customs and moral concerns of 17th-century Dutch society, a society that was grappling with newfound prosperity and its implications. He was also influenced in his peasant scenes by artists like Pieter de Bloot and Hendrick Martensz. Sorgh, who specialized in depicting rural life.

Landscape Painting: Panoramic Vistas

Although Salomon Koninck's reputation rests more heavily on his figural compositions, he also engaged with landscape painting. His approach to landscape differed from the more naturalistic or dramatic styles of specialists like Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1628/29–1682) or Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709). Koninck often favored idealized, panoramic views, typically seen from an elevated vantage point, offering expansive vistas of rolling countryside dotted with villages or architectural elements.

His painting "Village on a Hill" (1651) is considered a significant work in this genre, showcasing his ability to create a sense of depth and atmospheric perspective. These landscapes often possess a serene, almost poetic quality, emphasizing harmony and order in nature. While perhaps not as central to his output as other genres, his landscapes demonstrate his versatility and his engagement with the diverse artistic trends of his time. His brother, Jacob Koninck (c. 1614/15–c. 1690), was also a landscape painter, suggesting a familial interest in this genre. The influence of Hercules Seghers (c. 1589/90–c. 1638), known for his highly original and often fantastical landscapes, can also be discerned in the imaginative scope of some Dutch landscape painting of this era, though Koninck's own were generally more grounded.

Notable Works and Their Significance

Several of Salomon Koninck's paintings stand out for their artistic merit and historical importance:

"Philosopher with a Classical Book" (or "A Philosopher"): This work, often linked with Rembrandt, exemplifies Koninck's mastery of chiaroscuro and his ability to convey intellectual depth and introspection. The warm lighting, focused on the philosopher's face and the open book, creates an intimate and contemplative atmosphere.

"Joseph Explaining Pharaoh's Dreams": A powerful biblical narrative, this painting showcases Koninck's skill in compositional arrangement and dramatic storytelling. The expressions and gestures of the figures effectively convey the tension and significance of the moment.

"The Gold-weigher": This genre scene is rich in symbolism, reflecting contemporary concerns about wealth and morality. The meticulous detail and expressive characterization make it a compelling example of Dutch moralizing painting.

"Alchemist Cutting His Nails": This intriguing painting delves into the world of esoteric knowledge, a popular theme in the 17th century. It captures the secretive and meticulous nature of the alchemist's pursuits.

"A Scholar Sharpening His Quill" (1639): This painting gained unfortunate notoriety when it was looted by the Nazis during World War II. Its eventual restitution to the Adolphe Schloss family highlights the tragic impact of war on cultural heritage and the ongoing efforts to redress historical injustices.

"The Old Bishop" (1648): A testament to his skill in portraiture, this work captures the dignity and wisdom of the elderly clergyman with sensitivity and technical finesse.

"Village on a Hill" (1651): Representing his landscape work, this painting offers a sweeping, idealized view of the Dutch countryside, demonstrating his ability to create atmospheric depth and a sense of tranquility.

These works, now housed in prestigious museums and collections worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, attest to Koninck's artistic achievements and his place within the Dutch Golden Age.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu of Amsterdam

Salomon Koninck operated within an incredibly dynamic and competitive artistic environment. Amsterdam in the 17th century was a magnet for artists, and Koninck would have been aware of, and likely interacted with, many leading figures. Beyond Rembrandt, his circle and contemporaries included a host of talented painters.

Ferdinand Bol (1616–1680) and Govert Flinck (1615–1660) were prominent pupils of Rembrandt who achieved considerable success, particularly in portraiture and historical painting. Their careers, like Koninck's, were shaped by Rembrandt's influence, though they later developed more classically elegant styles to suit prevailing tastes. Carel Fabritius (1622–1654), another brilliant Rembrandt pupil, was known for his innovative use of perspective and light before his tragic early death.

In the realm of genre painting, artists like Gerard Dou (1613–1675), a founder of the Leiden "fijnschilders" (fine painters), were celebrated for their meticulously detailed and highly polished scenes of everyday life. Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667) and Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684) also excelled in creating intimate and refined genre interiors, often depicting domestic scenes with remarkable sensitivity to light and texture. While Koninck's genre works were perhaps less numerous, they shared the Dutch preoccupation with capturing the nuances of daily existence and its moral undertones.

The poet Joost van den Vondel (1587–1679), a towering figure in Dutch literature and a friend of Rembrandt, also moved in these artistic circles. Vondel is known to have written poems for portraits, including some possibly by artists in Rembrandt's sphere, highlighting the interplay between visual art and literature during this period. Koninck's family life also connected him to the art world; he married a daughter of the painter Adriaen van Neerland, and later, after her passing, married a second time.

The art market in Amsterdam was sophisticated, with collectors from various social strata, including wealthy merchants, civic institutions, and even ordinary citizens. This broad patronage supported a wide range of artistic production and fostered a climate of innovation and competition. Koninck, like his contemporaries, would have navigated this market, seeking commissions and selling his works through dealers or directly to clients.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

Information about Salomon Koninck's later years suggests a possible shift in his activities. It is believed that in the last decade of his life, his artistic output decreased significantly, possibly because he became more involved in business pursuits, perhaps related to his father's trade or other mercantile ventures common in Amsterdam. This was not unusual for artists of the period, many of whom had other sources of income.

Salomon Koninck died in Amsterdam and was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) on August 8, 1656. He left behind a significant body of work that reflects the artistic concerns and achievements of the Dutch Golden Age.

His reputation has experienced fluctuations over time. During his lifetime and shortly thereafter, his works were collected and appreciated, not only in the Netherlands but also in countries like France and Germany. However, the overwhelming fame of Rembrandt sometimes led to Koninck's contributions being overshadowed or, as mentioned, his works being misattributed.

In the 19th century, with a renewed interest in Realism and the Dutch Golden Age masters, artists and collectors rediscovered figures like Koninck. The 20th century saw further scholarly attention devoted to him, leading to a more nuanced understanding of his place in art history. Art historians today recognize Salomon Koninck as a talented and versatile painter who, while deeply influenced by Rembrandt, developed his own distinctive voice. He is valued for his warm palette, his psychological insight, his skillful handling of light and texture, and his ability to convey profound human emotions.

His paintings continue to be studied for their technical mastery and their insights into the cultural and intellectual life of 17th-century Holland. They reveal an artist who was deeply engaged with the artistic currents of his time, contributing to the rich legacy of the Dutch Golden Age. While he may not have achieved the universal fame of a Rembrandt or a Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), Salomon Koninck remains an important figure, a testament to the depth and breadth of talent that characterized one of art history's most brilliant periods. His works offer a window into a world of scholarship, faith, and everyday life, rendered with a skill and sensitivity that continue to resonate with viewers today. His connection to other artists, whether as a student of David Colyns, an admirer of Pieter Lastman's narrative power, or a contemporary of figures like Jan Lievens (1607-1674) who also shared an early association with Rembrandt, places him firmly within the intricate web of artistic relationships that defined the era.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Salomon Koninck's journey as an artist reflects the dynamism and richness of the Dutch Golden Age. From his early training in Amsterdam to his mature works that resonate with the influence of Rembrandt, Koninck carved out a distinct artistic identity. He excelled in portraying the contemplative world of scholars and philosophers, the dramatic narratives of the Bible, and the characterful faces of his sitters. His warm palette, masterful use of chiaroscuro, and ability to imbue his subjects with psychological depth are hallmarks of his style.

Though sometimes overshadowed by the colossal figure of Rembrandt, and his works occasionally mistaken for those of his more famous contemporary, Koninck's artistic merit is undeniable. He was a skilled craftsman and a thoughtful interpreter of the human condition, contributing significantly to the genres of portraiture, religious painting, and genre scenes. His legacy is preserved in the numerous paintings held in collections around the world, each a testament to his talent and his engagement with the vibrant artistic culture of 17th-century Amsterdam. As an art historian, one appreciates Salomon Koninck not just as a follower of a greater master, but as a gifted artist in his own right, whose works offer enduring insights and aesthetic pleasure, securing his place as a notable luminary of a truly golden era in art.