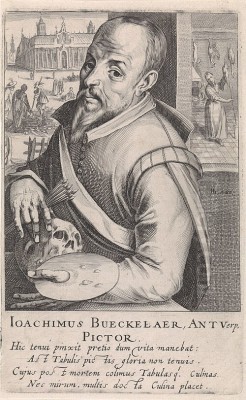

Introduction: An Antwerp Luminary

Joachim Beuckelaer stands as a pivotal figure in the rich tapestry of 16th-century Flemish painting. Active during Antwerp's Golden Age, he carved a unique niche for himself, specializing in vibrant and bustling market and kitchen scenes. These works, teeming with meticulously rendered foodstuffs, household objects, and lively figures, not only captured the spirit of his time but also played a crucial role in the development of still life and genre painting in Northern Europe and beyond. Deeply connected to the artistic traditions of Antwerp, particularly through his relationship with his uncle and teacher, Pieter Aertsen, Beuckelaer absorbed and then significantly expanded upon the visual language he inherited, leaving behind a legacy that influenced generations of artists.

His paintings are more than mere depictions of everyday life; they are often complex allegories, embedding religious or moral narratives within the seemingly mundane. This fusion of the sacred and the secular, rendered with remarkable technical skill and a keen eye for detail, defines Beuckelaer's contribution. He navigated the complex cultural currents of his era—a time of burgeoning commerce, religious upheaval, and evolving artistic tastes—to create a body of work that remains fascinating for its visual richness and symbolic depth. Understanding Beuckelaer is key to appreciating the evolution of Netherlandish art in the later Renaissance.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Joachim Beuckelaer was born in Antwerp, the bustling commercial heart of the Spanish Netherlands, though the exact year remains debated by scholars, typically cited as either circa 1530 or 1533. He hailed from a family seemingly steeped in the painter's craft. While details are scarce, it is believed his father may have been the painter Matthaeus Beuckeleer. Furthermore, his brother, Huybrecht Beuckeleer, also pursued a career as a painter, indicating a familial environment where artistic skills were likely nurtured from a young age. This background provided a solid foundation for his future career within Antwerp's competitive artistic milieu.

The most significant formative influence on Beuckelaer was undoubtedly his uncle, Pieter Aertsen. Aertsen was already a highly respected and innovative painter, particularly known for popularizing large-scale market and kitchen scenes where still life elements often dominated the foreground, relegating religious scenes to the background. Beuckelaer entered Aertsen's workshop as an apprentice, learning the techniques and thematic concerns that characterized his uncle's output. This period of training was crucial, equipping him with the skills in composition, colour, and detailed rendering that would become hallmarks of his own style.

Having completed his apprenticeship, Joachim Beuckelaer achieved a significant milestone in 1560 when he was registered as an independent master in the prestigious Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke. This membership granted him the right to establish his own workshop, take on apprentices, and sell his works independently. From this point forward, Beuckelaer embarked on a productive, albeit relatively short, career, building upon the foundations laid by Aertsen while forging his own distinct artistic identity within the vibrant Antwerp school. He remained active in Antwerp until his death, the date of which is also uncertain, placed around 1573 or 1574.

Artistic Style: Detail, Colour, and Narrative Complexity

Joachim Beuckelaer's artistic style is immediately recognizable for its robust realism, meticulous attention to detail, and vibrant colour palette. He possessed an extraordinary ability to render the textures and surfaces of a vast array of objects – the glistening scales of fish, the rough skins of vegetables, the gleam of metalware, and the varied fabrics of clothing. His compositions are often densely packed, creating a sense of abundance and bustling activity that reflects the commercial energy of 16th-century Antwerp.

While inheriting the market and kitchen themes from Pieter Aertsen, Beuckelaer often pushed the level of detail and compositional complexity further. Some art historians argue that his technical proficiency, particularly in the rendering of still life elements, even surpassed that of his master. He arranged his subjects – fruits, vegetables, meats, fish, poultry, and household utensils – with a deliberate sense of order within the apparent chaos, inviting the viewer's eye to explore the wealth of visual information presented.

A defining characteristic of Beuckelaer's work is the sophisticated interplay between foreground genre scenes and background narratives, which are frequently religious. Unlike purely secular genre paintings that would emerge later, Beuckelaer's works often function on multiple levels. The detailed depiction of worldly goods in the foreground might contrast with a small biblical scene unfolding in the distance, prompting moral reflection on themes such as earthly temptation versus spiritual salvation, or the bounty of God's creation. This narrative layering adds intellectual depth to the visual feast.

The World of Markets and Kitchens

Beuckelaer's name is virtually synonymous with the market and kitchen scenes that dominated his output. These paintings offer invaluable glimpses into the daily life, commerce, and culinary habits of Antwerp during its peak as a major European trading hub. His canvases come alive with the vibrant atmosphere of open-air markets and the busy interiors of kitchens, populated by vendors, maids, cooks, and customers.

The sheer variety of goods depicted is astonishing. Fish stalls overflow with herring, cod, plaice, and shellfish; vegetable stands are piled high with cabbages, carrots, artichokes, and gourds; butchers display cuts of meat and poultry. These are not just random assortments; Beuckelaer often seems to revel in the specific details of each item, capturing their individual forms and textures with loving precision. This detailed inventory reflects Antwerp's status as a center where goods from across the known world were available.

The figures inhabiting these scenes are typically robust and earthy, engaged in the activities of buying, selling, preparing food, or interacting with one another. While sometimes appearing somewhat stylized, they contribute significantly to the narrative and atmosphere. Their gestures and expressions, combined with the abundance surrounding them, create dynamic compositions that are both realistic representations and carefully constructed artistic statements. These scenes established a popular genre that resonated with the increasingly prosperous urban clientele of the time.

Pioneering Still Life Painting

While Pieter Aertsen laid crucial groundwork, Joachim Beuckelaer took significant steps in advancing still life towards an independent genre. In many of his market and kitchen scenes, the meticulously painted arrays of food and objects in the foreground command as much, if not more, attention than the human figures or background narratives. This emphasis on the inanimate, rendered with such palpable realism, anticipates the dedicated still life paintings that would flourish in the Netherlands in the following century.

Works like his famous Four Elements series demonstrate this tendency. While ostensibly allegorical and containing figures, the overwhelming impression is often one of stunningly depicted natural produce and man-made objects. The sheer visual weight and detailed execution of the fish in Water, the vegetables and fruits in Earth, or the cooked meats and kitchen implements in Fire, push the boundaries between genre scene and still life. He created compositions where the 'stuff' of the world took center stage.

Beuckelaer can be considered a pioneer in developing compositions that were essentially still lifes, even if they often retained a nominal human or narrative element, distinguishing them from the purely object-focused still lifes of later artists like Clara Peeters or Frans Snyders. He explored the potential of inanimate objects to carry meaning, convey texture and form, and create visually compelling arrangements. His work provided a vital bridge between the earlier integration of still life elements into larger compositions and the emergence of still life as a respected, independent genre.

Symbolism and Allegory: Reading Between the Lines

Beuckelaer's paintings are rarely just what they seem; they are rich repositories of symbolism and allegory, reflecting the moral and religious concerns of his time. The detailed realism serves not only aesthetic purposes but also functions as a vehicle for deeper meaning. He employed a visual language understood by his contemporaries, where specific objects or arrangements could evoke biblical references, moral lessons, or philosophical ideas.

The Four Elements series (c. 1569-1570) is a prime example of his allegorical approach. Each painting represents one of the classical elements through a related market or kitchen scene. Water, famously housed in the National Gallery, London, depicts a fish market. The abundance of fish, often featuring twelve distinct types, is interpreted as symbolizing the twelve apostles, while a tiny background scene shows the resurrected Christ by the Sea of Galilee – the Miraculous Draught of Fishes. This juxtaposition invites contemplation on sustenance, faith, and miracles.

Similarly, Earth typically showcases a fruit and vegetable market, symbolizing the bounty and fertility of the land provided by God. Fire often presents a kitchen scene, focusing on cooked meats and the hearth, representing warmth and transformation but potentially also hinting at worldly pleasures or even the fires of hell. Air might feature a poultry market, linking birds to the realm of the sky. Through these works, Beuckelaer explored the fundamental components of the world while embedding Christian interpretations.

Beyond this series, symbolism permeates his work. The abundance of food could signify divine providence but also warn against gluttony and excessive attachment to worldly goods, a common theme in Northern Renaissance art, also explored by contemporaries like Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Background biblical scenes, such as the Flight into Egypt appearing behind a bustling market, or Christ in the House of Martha and Mary set within a detailed kitchen, constantly remind the viewer of the spiritual dimension underlying everyday existence. The contrast between the active, worldly foreground and the often ignored spiritual background serves as a moral commentary.

Representative Works: A Visual Legacy

Joachim Beuckelaer's surviving oeuvre includes several masterpieces that exemplify his style and thematic concerns.

The Four Elements (c. 1569-70): This series remains perhaps his most ambitious and well-known project. As discussed, each painting (Water, Earth, Air, Fire) uses a market or kitchen setting to allegorize one of the classical elements, embedding rich layers of symbolism and often a small background religious scene. Water (National Gallery, London) and Earth are particularly celebrated for their stunning depictions of produce.

Fish Market (1568; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): A quintessential Beuckelaer market scene, this large canvas presents a vibrant, almost overwhelming display of fish and seafood, alongside robust market figures. It showcases his mastery in rendering textures and his ability to organize complex, crowded compositions effectively. It likely carries symbolic weight related to Christ and the apostles, similar to The Four Elements: Water.

Vegetable Market (e.g., 1567; Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent): Several versions exist, depicting stalls overflowing with colourful vegetables and fruits. These works highlight the agricultural bounty available in Antwerp and demonstrate Beuckelaer's skill in capturing the specific forms and colours of various produce, contributing significantly to the development of still life.

Poultry Market (e.g., Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels): Similar to his fish and vegetable markets, these scenes focus on the sale of chickens, ducks, and other fowl. They often include lively interactions between vendors and customers and showcase his ability to paint feathers and flesh realistically.

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (e.g., 1565; Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels; other versions exist): This subject, also tackled by Aertsen, was a favourite for Beuckelaer. It allowed him to combine a detailed kitchen interior, filled with food and utensils (representing Martha's worldly concerns), with the religious narrative of Christ visiting the sisters, praising Mary's choice to listen rather than labour. The contrast between the spiritual and the material is central.

The Flight into Egypt: Often depicted as a background scene in a larger market painting, this biblical story provided another opportunity to juxtapose the sacred journey of the Holy Family with the mundane, sometimes oblivious, activities of everyday commerce.

Ecce Homo / Market Scene (Uffizi Gallery, Florence): This work cleverly integrates the biblical scene of Christ being presented to the crowd (Ecce Homo) into the background of a bustling foreground market, likely a vegetable market. It's a powerful example of embedding profound religious drama within an everyday setting, forcing the viewer to look past the immediate worldly display.

Other notable works include scenes like Slaughtering a Pig, depictions of the Miraculous Draught of Fishes, the Adoration of the Shepherds, and Isaac Blessing Jacob, all demonstrating his versatility in combining genre elements with religious narratives and his consistent attention to realistic detail.

The Artist's Process and Workshop Practice

Understanding Joachim Beuckelaer's working methods sheds light on his artistic production. Technical analysis, including the use of infrared reflectography (IRR), has revealed aspects of his creative process. IRR often uncovers detailed underdrawings beneath the paint layers, showing that Beuckelaer planned his compositions carefully, sometimes making significant adjustments between the initial sketch and the final painted version. For instance, studies of works like the Adoration of the Shepherds show him altering the position of figures' limbs to achieve better compositional balance.

Like most successful artists of his time, Beuckelaer likely maintained an active workshop. He would have employed assistants and apprentices to help with tasks such as preparing panels, grinding pigments, painting backgrounds, or even producing replicas or variations of popular compositions. The existence of multiple versions of some of his paintings supports this idea. His brother, Huybrecht Beuckelaer, may have worked in the workshop, and his style sometimes closely resembles Joachim's, leading to occasional attribution difficulties.

Beuckelaer seems to have utilized a stock of models and patterns, both drawn and perhaps physical props, within his studio. Certain motifs, figures, or arrangements of objects reappear across different paintings, suggesting the use of preparatory studies or cartoons that could be adapted and reused. He clearly drew inspiration from his master, Pieter Aertsen, sometimes borrowing figures or compositional ideas, but always adapting them into his own energetic and densely packed style. His meticulous rendering suggests close observation of actual objects, likely sketched from life before being incorporated into larger, complex scenes.

The Enduring Dialogue with Pieter Aertsen

The artistic relationship between Joachim Beuckelaer and his uncle, Pieter Aertsen, is fundamental to understanding Beuckelaer's career. It was a dynamic interaction that went beyond a simple master-pupil transmission. Beuckelaer absorbed Aertsen's innovations – the monumentalization of market and kitchen scenes, the prominent placement of still life elements, and the integration of religious narratives into everyday settings. He adopted Aertsen's subject matter wholesale in the early part of his independent career.

However, Beuckelaer did not merely imitate. He intensified many aspects of Aertsen's style. His compositions are often more crowded, his colours perhaps brighter and more varied, and his rendering of details arguably even more precise. While Aertsen's figures can sometimes possess a greater sense of monumentality or classical influence (perhaps reflecting Aertsen's time spent outside Antwerp), Beuckelaer's figures are often earthier, more animated, and fully integrated into the bustling environment.

The theme of Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, painted by both artists, offers a good point of comparison, revealing shared compositional strategies but also subtle differences in emphasis and mood. Both artists used the format to explore the tension between worldly duties and spiritual contemplation. Beuckelaer's development of still life elements, pushing them towards near independence, can be seen as extending Aertsen's initial explorations. While deeply indebted to his uncle, Beuckelaer ultimately forged a distinct and powerful artistic personality, contributing significantly to the trajectory of Netherlandish painting.

Influence and Legacy: Spreading the Seeds of Genre and Still Life

Joachim Beuckelaer's impact extended well beyond his own lifetime and geographical location. Within Antwerp, he was a significant figure in the city's artistic school, contributing to its reputation as a center for innovative genre and still life painting alongside contemporaries like Frans Floris and Marten de Vos. His detailed, vibrant style provided a model for subsequent generations of Flemish artists.

His influence was particularly strong in the development of still life. The emphasis he placed on the realistic depiction of food and objects paved the way for later Flemish masters of the genre, such as Frans Snyders and Jan Brueghel the Elder, who specialized in elaborate displays of abundance, albeit often shedding the overt religious allegory found in Beuckelaer's work. His market scenes also contributed to a tradition continued by artists who focused on peasant life and markets.

Beuckelaer's works were exported and became known outside the Netherlands, notably in Italy. His market and kitchen scenes found resonance with North Italian painters who were exploring similar themes. Artists like Vincenzo Campi in Cremona and Bartolomeo Passerotti in Bologna adopted similar subject matter and a robust, realistic style that clearly shows Beuckelaer's influence. Even the great Annibale Carracci, one of the founders of the Baroque style in Italy, painted early works like The Butcher's Shop that echo the earthy realism and genre focus seen in Beuckelaer and Aertsen. The Bassano family workshop in Venice, particularly Jacopo Bassano, also explored the fusion of rustic genre scenes with religious subjects in a manner comparable to Beuckelaer.

Despite his influence, Karel van Mander, an early biographer of Netherlandish artists, noted that Beuckelaer struggled to sell his works for high prices during his lifetime, only achieving better financial success towards the end of his career. Nevertheless, his paintings were collected and appreciated, and his pioneering role in developing key genres ensured his lasting importance in the history of European art.

Later Life and Enduring Significance

Details about Joachim Beuckelaer's later life remain scarce. He continued to be active in Antwerp throughout the 1560s and into the early 1570s, producing the works upon which his reputation rests. His death, generally placed around 1573 or 1574, brought a premature end to the career of one of Antwerp's most distinctive artistic voices.

In conclusion, Joachim Beuckelaer was far more than just a painter of groceries. He was a technically brilliant artist who captured the vibrant material culture of his time while simultaneously engaging with profound religious and moral themes. He masterfully blended detailed realism with complex allegory, creating works that are both visually engaging and intellectually stimulating. As a crucial link between the innovations of Pieter Aertsen and the flourishing of still life and genre painting in the 17th century, and as an influence that reached as far as Italy, Beuckelaer holds a significant and enduring place in the history of Western art. His bustling markets and kitchens continue to offer a vivid window onto the world of the 16th-century Netherlands.