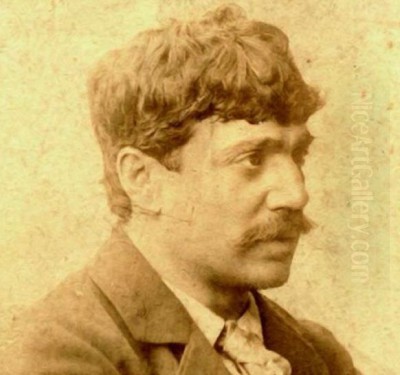

Simon Hollósy stands as a monumental figure in the annals of Hungarian art history, an artist and educator whose influence rippled through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born on February 2, 1857, in Máramarossziget, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary (now Sighetu Marmației, Romania), to Armenian parents, Hollósy's journey would see him challenge academic conventions and become a beacon for a new generation of artists seeking truth and authenticity in their work. He passed away on May 8, 1918, in Técső (now Tyachiv, Ukraine), leaving behind a rich legacy that continues to inform Hungarian art. His commitment to Naturalism, Realism, and plein-air painting, coupled with his charismatic teaching, made him a central catalyst in the modernization of Hungarian art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Hollósy's early artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training, a common path for aspiring painters of his era. He initially studied in Budapest before making his way to Munich, which was then a major European art hub, rivaling Paris in its academic offerings and attracting students from across the continent. The Munich Academy of Fine Arts was renowned for its rigorous, traditional curriculum, emphasizing drawing from plaster casts and historical compositions.

However, Hollósy, like many of his forward-thinking contemporaries, grew dissatisfied with the rigid and often stifling atmosphere of academic training. He found the prevailing historical painting and sentimental genre scenes increasingly disconnected from the realities of modern life. This period of questioning was crucial, as it set him on a path of independent exploration and a search for more direct and honest forms of artistic expression.

The Munich Years: A Turn Towards Realism

During his time in Munich, Hollósy was profoundly influenced by the burgeoning Realist movement, particularly the work of the French painter Gustave Courbet. Courbet's revolutionary stance against academic idealism, his focus on the unvarnished realities of peasant life and the common man, and his robust, often earthy, painting technique offered a powerful alternative to the polished, anodyne art favored by the academies. Hollósy absorbed these influences, recognizing the power of art to reflect contemporary life with sincerity.

He also became acquainted with the principles of Naturalism, a related movement that sought an even more objective and detailed representation of reality, often with a focus on rural subjects and the effects of light and atmosphere. The works of French artists like Jean-François Millet, known for his dignified portrayals of peasant labor, and Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose plein-air Naturalism gained immense popularity, were significant in shaping the artistic landscape that Hollósy navigated. Bastien-Lepage, in particular, became a model for many young artists in Munich who were eager to paint outdoors and capture the nuances of natural light.

This intellectual and artistic ferment led Hollósy to a critical decision. Instead of continuing within the established academic system, he chose to forge his own path, one that prioritized direct observation, truth to nature, and a more personal engagement with his subjects.

Founding a Private School in Munich

In 1886, Simon Hollósy took a significant step by establishing his own private art school in Munich. This was a bold move, positioning him as an alternative to the official Academy. His school quickly gained a reputation for its progressive teaching methods and its charismatic director. It attracted a diverse and international student body, including aspiring artists from Hungary, Poland, Russia, Germany, and Switzerland.

Hollósy's teaching philosophy was a departure from the rote learning of the Academy. He encouraged his students to develop their individual talents, to observe nature keenly, and to paint with honesty. He emphasized the importance of studying the works of modern masters, particularly the French Realists and Naturalists, and he championed the practice of plein-air painting – painting outdoors directly from the subject. This approach allowed for a more immediate and accurate rendering of light, color, and atmosphere.

His school became a lively center for artistic exchange and a training ground for many who would later become significant figures in their respective national art scenes. The environment was one of critical inquiry and a shared enthusiasm for new artistic directions. It was here that Hollósy began to gather a circle of devoted Hungarian students who would play a crucial role in his next major endeavor. Among his contemporaries in Munich running private schools was the Slovenian painter Anton Ažbe, whose school also attracted an international clientele, including figures like Wassily Kandinsky and Alexej von Jawlensky, highlighting Munich's role as a crucible for new artistic ideas outside the formal Academy.

The Genesis of the Nagybánya Artists' Colony

The desire for a more immersive experience of nature and a deeper connection to their Hungarian roots led Hollósy and his circle to a groundbreaking decision. In the summer of 1896, Hollósy, along with his students and fellow artists István Réti, János Thorma, Károly Ferenczy, and Béla Iványi-Grünwald, established an artists' colony in Nagybánya (now Baia Mare, Romania). This picturesque mining town, nestled in a valley surrounded by mountains, offered an ideal setting for their artistic aspirations.

The Nagybánya colony was conceived as a place where artists could live and work in close communion with nature, free from the constraints of urban academic life. It was a conscious effort to create a Hungarian school of painting grounded in plein-air principles and focused on capturing the unique light, landscapes, and life of their homeland. The colony quickly became the most influential center for modern art in Hungary.

Hollósy was the intellectual leader and guiding spirit of Nagybánya in its early years. His enthusiasm for plein-air painting and his commitment to Naturalism set the tone for the colony's artistic direction. The artists of Nagybánya dedicated themselves to observing and depicting the local scenery, the changing seasons, and the lives of the town's inhabitants.

Life and Art at Nagybánya

The Nagybánya artists' colony was more than just a summer painting location; it evolved into a year-round community with a distinct artistic philosophy. The core tenets were the direct study of nature, the importance of light and color in capturing atmospheric effects, and a commitment to depicting subjects with truthfulness and sincerity. This marked a significant departure from the studio-bound, often formulaic, practices of academic art.

The artists, under Hollósy's guidance, would venture into the surrounding countryside, easels in hand, to capture the fleeting moments of light and the authentic character of the landscape. Their subject matter ranged from sun-dappled forests and tranquil rivers to scenes of rural labor and portraits of local people. The emphasis was on capturing the "impression" of a scene, though their style was generally rooted in Naturalism rather than the broken brushwork of French Impressionism as practiced by artists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro.

The colony organized regular exhibitions, both locally and in Budapest, which helped to disseminate their new artistic vision to a wider audience. These exhibitions often sparked debate, as their modern approach challenged the established tastes of the Hungarian art world, which was still largely dominated by academic historicism and Biedermeier genre painting. Figures like Pál Szinyei Merse had earlier pioneered plein-air painting in Hungary with works like Picnic in May, but Nagybánya institutionalized this approach and gave it a collective force.

Hollósy's Pedagogical Approach: "Feeling, Not Painting"

As a teacher, Simon Hollósy was both inspiring and demanding. His pedagogical philosophy could be encapsulated in his famous dictum, "Érezni és nem festeni" – "To feel, not (just) to paint." This emphasized that technical skill alone was insufficient; true art required a deep emotional connection with the subject and the ability to convey that feeling through the medium of paint.

He encouraged his students to develop their own individual styles rather than merely imitating his own. He fostered an environment of critical discussion and mutual support, where artists could learn from each other as well as from nature. His teaching extended beyond the technical aspects of painting to encompass a broader understanding of art's role in society and its capacity for expressing human experience.

Hollósy's influence as an educator was profound. Many of his students went on to become leading figures in Hungarian art, each developing their unique artistic voice while often retaining the foundational principles of plein-air painting and truth to nature that they had learned under his tutelage. His impact was not limited to Hungarians; artists from other countries who studied with him also carried his ideas back to their homelands.

Key Works and Artistic Style

Simon Hollósy's own artistic output, while perhaps less voluminous than some of his contemporaries due to his dedication to teaching, includes several seminal works that exemplify his artistic principles. His style is characterized by a strong commitment to Realism and Naturalism, a keen observation of light and atmosphere, and a sympathetic portrayal of his subjects.

One of his most celebrated early works is Kukoricatörés (Corn Husking), painted in 1885. This large-scale genre scene depicts peasants husking corn, rendered with meticulous detail and a profound sense of dignity. The painting showcases his mastery of composition, his ability to capture individual character, and his deep empathy for rural life. It stands as a quintessential example of 19th-century Hungarian Naturalism.

Another significant work is the Rákóczi-induló (Rákóczi March), a historical composition that, while different from his typical genre scenes, demonstrates his versatility and his engagement with national themes. He also painted numerous landscapes, particularly during his time at Nagybánya and later at Técső, which reveal his sensitivity to the nuances of light and color in the natural world. Works like Tájrészlet Técsőn (Landscape in Técső) or Szalmakazlak lemenő napnál (Haystacks in Sunset, also known as Scenes of the Day) highlight his dedication to plein-air observation.

His portraits, such as his Self-Portrait or Girl, are characterized by their psychological insight and their unpretentious honesty. Throughout his career, Hollósy remained committed to depicting the world around him with truthfulness, whether it was the grandeur of a landscape, the quiet dignity of a peasant, or the intimate character of a portrait. While influenced by Impressionistic concerns for light, his work generally maintained a more solid, descriptive form than that of the French Impressionists.

Other notable works mentioned include Summer and the ambitious composition Nihilisták sorsot húznak (Nihilists Drawing Lots), which is housed in the Déri Museum in Debrecen. His later painting, Autumn (1916), shows his continued exploration of landscape themes with mature skill.

Divergences and the Técső Period

Despite his foundational role at Nagybánya, Hollósy's relationship with the colony evolved. Over time, differences in artistic direction and perhaps personality led to a degree of estrangement from some of the other leading figures, such as Károly Ferenczy and István Réti, who themselves became powerful forces within the colony. While Ferenczy developed a distinctive, highly personal style that incorporated elements of Post-Impressionism and decorative tendencies, and Réti became an important chronicler and theorist of the Nagybánya movement, Hollósy remained more steadfastly committed to his particular brand of Naturalism.

These divergences, coupled with his somewhat restless nature and perhaps a feeling that his works were not exhibited as frequently as he might have wished, led Hollósy to spend more time away from Nagybánya's core activities. From 1902, he began to take his students to Técső (Tyachiv) in the summers, a smaller town further east in the Subcarpathian region, where he established his own summer painting school.

In Técső, Hollósy continued his pedagogical work, focusing on plein-air painting and encouraging his students to capture the local landscapes and folk life. This period saw him produce many landscapes characterized by their fresh observation and vibrant color. The Técső school, while less famous than Nagybánya, represented a continuation of Hollósy's commitment to his artistic and educational ideals in a new setting. He remained in Técső until his death in 1918.

Influence and Legacy

Simon Hollósy's influence on Hungarian art is undeniable and multifaceted. Through his teaching, both in Munich and at Nagybánya and Técső, he mentored a generation of artists who would go on to shape the course of Hungarian modernism. He instilled in them a respect for nature, a commitment to truthfulness, and the courage to break from academic convention.

The Nagybánya colony, which he co-founded, became the single most important catalyst for the renewal of Hungarian painting. It introduced and popularized plein-air painting, Naturalism, and, to some extent, Impressionistic tendencies, paving the way for subsequent avant-garde movements in Hungary. Artists like József Rippl-Rónai, who was associated with the Parisian Nabis group, also contributed to Hungarian modernism, but Nagybánya's impact was arguably more widespread within Hungary itself, particularly in its initial phase.

Hollósy's emphasis on "feeling" in art encouraged a more subjective and personal approach to painting, moving beyond mere technical proficiency. He helped to foster a sense of national artistic identity by encouraging artists to find inspiration in Hungarian landscapes and life, a contrast to the often international or historical themes favored by the Academy. His legacy can be seen in the work of his direct students and in the broader shift within Hungarian art towards modernism. Even artists who eventually moved in different stylistic directions often acknowledged the foundational importance of their training with Hollósy or their engagement with the Nagybánya principles.

Hollósy and His Contemporaries

Simon Hollósy's career unfolded during a dynamic period in European art, and his interactions and relationships with contemporary artists were crucial to his development and influence.

His primary collaborators and, in some cases, friendly rivals, were the co-founders and leading figures of Nagybánya:

Károly Ferenczy: Initially a close associate, Ferenczy became one of the most important painters of the Nagybánya school, developing a distinctive style characterized by rich color and decorative compositions. His work evolved significantly over his career, absorbing various modern influences.

István Réti: A loyal student and later a key figure at Nagybánya, Réti was not only a painter but also an important art historian and theorist who documented the colony's history and principles.

János Thorma: Another co-founder, Thorma was known for his large-scale historical paintings as well as his Nagybánya landscapes. He remained a central figure in Nagybánya for many decades.

Béla Iványi-Grünwald: A founding member, Iványi-Grünwald was a versatile artist whose style evolved from early Naturalism towards more decorative and colorful approaches, later founding the Kecskemét artists' colony.

Beyond this core group, Hollósy taught numerous other students who made their mark, such as Imre Révész, known for his genre scenes, and even figures like Ervin Baktay, who later became a renowned Indologist but studied art with Hollósy in his youth. The Polish painter Władysław Ślewiński, associated with the Pont-Aven school and Paul Gauguin, also reportedly spent time at Hollósy's Munich school, indicating its international reach.

In the broader Hungarian context, Hollósy's work can be seen in relation to figures like:

Mihály Munkácsy: An older, internationally famous Hungarian Realist, Munkácsy's dramatic genre scenes and biblical paintings represented a different facet of 19th-century Realism, often more studio-based and theatrical than Hollósy's Naturalism.

Pál Szinyei Merse: A pioneer of Hungarian plein-air painting and Impressionism, Szinyei Merse's early works prefigured some of Nagybánya's concerns, though he worked in relative isolation for a period.

Internationally, Hollósy's admiration for Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet is well-documented. He also encouraged study of Jules Bastien-Lepage. The broader Impressionist movement, with figures like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, provided a backdrop of radical innovation in light and color, elements of which were selectively absorbed and adapted by the Nagybánya artists. In Germany, artists like Max Liebermann were developing their own form of Impressionism, also drawing from Dutch and French influences, reflecting a parallel shift away from academicism in other European art centers.

Conclusion: An Enduring Impact

Simon Hollósy was more than just a talented painter; he was a visionary educator and a catalyst for change. His rejection of sterile academicism, his passionate advocacy for plein-air painting and Naturalism, and his ability to inspire and nurture young talent fundamentally altered the course of Hungarian art. The Nagybánya artists' colony, his most enduring legacy, became a crucible for modern Hungarian painting, fostering a spirit of innovation and a deep connection to the national landscape and identity.

While his personal artistic output might have been constrained by his dedication to teaching, the works he did create, such as Corn Husking and his many sensitive landscapes, stand as testaments to his skill and his artistic vision. Through his students and the enduring influence of Nagybánya, Simon Hollósy's spirit continues to resonate, securing his place as one of the most important figures in the history of Hungarian art. His life and work exemplify the transformative power of an artist who dares to challenge convention and dedicate himself to the pursuit of truth and feeling in art.