Introduction: An Artist of His Time

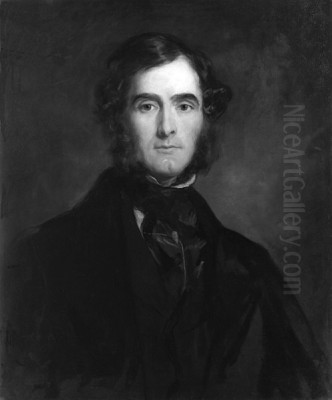

Sir Francis Grant stands as one of the most significant figures in British portrait painting during the mid-Victorian era. Born in Scotland in 1803 and passing away in 1878, his career spanned a period of immense social, political, and artistic change. Grant rose from an unconventional background, lacking formal artistic training, to become the favoured portraitist of the British aristocracy, political leaders, and even Queen Victoria herself. His eventual election as President of the Royal Academy of Arts cemented his position at the very pinnacle of the British art establishment. His work provides an invaluable visual record of the upper echelons of society during a defining period in British history.

Early Life and an Unconventional Path to Art

Francis Grant was born into privilege near Kilgraston in Perthshire, Scotland. He was the fourth son of Francis Grant, Laird of Kilgraston, a member of the Scottish landed gentry whose wealth was partly derived from plantations in Jamaica. Destined initially for a career in law, the young Grant showed little inclination for legal studies. His early life was more characterized by the pursuits typical of his class, particularly fox-hunting, a passion that would later inform some of his early artistic endeavours.

Upon inheriting £10,000 from his father, Grant quickly spent the fortune, primarily on his sporting interests. This financial imprudence, however, inadvertently steered him towards a professional career. Facing the need to earn a living, and possessing a natural aptitude for drawing, Grant made the rather unusual decision for a man of his background to become a professional artist. This was a time when the profession of painting, while respectable, was not typically pursued by members of the landed gentry who hadn't shown prodigious, early talent nurtured through formal channels.

Lacking formal instruction from an art academy, Grant honed his skills through diligent self-study. He spent time copying works by Old Masters, often pieces lent to him by supportive friends and family who recognised his nascent talent. This method, combined with his innate observational skills and understanding of anatomy, likely sharpened through his sporting life, allowed him to progress rapidly. His social connections undoubtedly provided him access to sitters and potential patrons from the outset, an advantage not available to artists from less privileged backgrounds.

Rise to Prominence: Sporting Scenes and Early Portraits

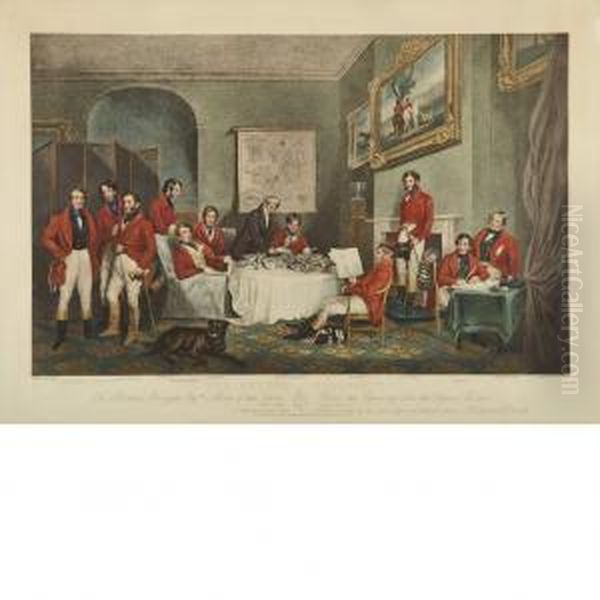

Grant's initial foray into the professional art world focused on subjects he knew intimately: sporting life. He became particularly known for his dynamic hunting scenes, often featuring members of the Melton Mowbray hunting set, an elite group of sportsmen based in Leicestershire. His first major public success came with his exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1834. Works like The Melton Breakfast (1834) captured the camaraderie and specific personalities of the hunt members in informal settings, demonstrating his skill in group portraiture and narrative.

During this early period, Grant often collaborated with the established sporting artist John Ferneley Sr. (1782-1860). Ferneley was renowned for his masterful depictions of horses, and in their joint works, Ferneley would typically paint the equine subjects while Grant focused on the human figures and overall composition. This partnership was mutually beneficial, allowing Grant to leverage Ferneley's reputation while contributing his own growing skill in portraiture. Paintings like The Melton Hunt (exhibited 1839) and The Cottesmore Hunt are prime examples of his work in this genre, celebrated for their accuracy, energy, and detailed depiction of the participants and the landscape.

Another significant early work was The Meeting of Her Majesty's Staghounds on Ascot Heath (exhibited 1837). This large, complex painting depicted numerous figures, including members of the aristocracy and Queen Victoria herself, participating in or observing the hunt. It showcased Grant's ambition and his ability to handle large-scale compositions involving multiple portraits, foreshadowing his future success as a society painter. While these sporting pictures established his reputation, Grant soon began to shift his focus primarily towards individual and group portraiture.

The Fashionable Portraitist of Victorian England

The turning point in Grant's career arguably came in 1840 when he received a commission to paint Queen Victoria. The resulting portrait, often depicting the young Queen on horseback, was highly successful and significantly boosted his profile. It opened doors to the highest levels of society, and Grant quickly became the portraitist du jour for the British elite. His studio became a fashionable destination for aristocrats, politicians, military leaders, and literary figures seeking to have their likeness captured by his skilled hand.

Grant possessed an innate understanding of his sitters and the social milieu they inhabited. His aristocratic background allowed him to interact with them as a social equal, putting them at ease and enabling him to capture not just a physical likeness but also a sense of their personality and status. His portraits were known for their elegance, refinement, and flattering yet fundamentally honest portrayal of the subject. He excelled at depicting the textures of luxurious fabrics, the glint of medals, and the subtle indicators of rank and breeding, all highly valued by his clientele.

His list of sitters reads like a 'Who's Who' of Victorian Britain. He painted Prime Ministers such as Lord Palmerston and Benjamin Disraeli, military heroes like Field Marshal Viscount Hardinge (painted 1849), and prominent literary figures including Sir Walter Scott (though Scott died in 1832, Grant painted his son-in-law and biographer, John Gibson Lockhart). He also painted numerous society beauties and landed gentry, capturing the confidence and poise of the ruling class. His success rivalled that of other contemporary portraitists, including the internationally renowned Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805-1873), who was also heavily favoured by European royalty, including Queen Victoria.

Artistic Style and Technique

Sir Francis Grant's style is firmly rooted in the British portrait tradition, evolving from the lineage of artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), who had dominated the field just before Grant's rise. However, Grant developed his own distinct approach. His work is characterized by a strong sense of realism, meticulous attention to detail, and sophisticated handling of paint. While capable of capturing grandeur, his portraits often possess a certain understated elegance and psychological insight.

His brushwork was typically smooth and refined, particularly in the rendering of faces and fabrics, though he could employ looser, more vigorous strokes in backgrounds or less critical areas. He had a keen eye for likeness, consistently producing portraits that were considered accurate representations by contemporaries. Beyond mere likeness, Grant excelled at conveying the character and social standing of his sitters through pose, expression, and the careful inclusion of attributes related to their profession or status.

Compared to the sometimes flamboyant style of Lawrence, Grant's work often appears more reserved, reflecting the somewhat more sober sensibilities of the early and mid-Victorian era. His colour palettes were generally rich but controlled, avoiding ostentation. He drew upon the traditions of aristocratic portraiture, particularly the work of Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), in his posing and compositional arrangements, especially for full-length portraits designed to convey authority and grace. Despite his lack of formal academic training, his technical proficiency was widely acknowledged.

Major Works and Lasting Images

Throughout his prolific career, Sir Francis Grant produced a substantial body of work, with estimates suggesting over 250 major portraits, alongside numerous other studies and paintings. Several works stand out as particularly representative of his oeuvre and impact:

Portraits of Queen Victoria: Grant painted Queen Victoria on several occasions. His equestrian portraits, such as the one commissioned in 1840, were particularly popular, capturing the young monarch's dignity and her fondness for riding. These images played a role in shaping the public perception of the Queen.

The Melton Breakfast (1834): An iconic early work depicting members of the Melton Hunt in a relaxed indoor setting. It's celebrated for its naturalistic grouping, individualised portraits, and evocation of sporting camaraderie.

The Meeting of Her Majesty's Staghounds on Ascot Heath (1837): A complex group portrait showcasing his ability to manage numerous figures and create a lively, detailed scene. It cemented his reputation early in his career.

John Gibson Lockhart: A sensitive portrait of Sir Walter Scott's son-in-law and biographer, capturing the intellectual and perhaps melancholic air of the sitter. It connects Grant directly to the legacy of one of Scotland's greatest writers.

Field Marshal Viscount Hardinge (1849): A powerful depiction of the military leader and Governor-General of India, showcasing Grant's ability to convey authority and martial bearing.

Anne Emily Sophia Grant, Mrs William Markham: A portrait of his own daughter, known as 'Daisy', painted around the time of her marriage. It displays a more intimate and personal touch, demonstrating his versatility.

Portrait of a Lady (1856): Housed in the Tate collection, this work exemplifies his elegant portrayal of female sitters, capturing both beauty and composure typical of Victorian ideals of femininity.

These works, alongside countless others depicting the political, social, and cultural leaders of the day, form a remarkable gallery of the Victorian establishment.

Service to the Royal Academy

Grant's success as a painter was mirrored by his rise within the institutional heart of the British art world, the Royal Academy of Arts in London. His association with the Academy began with his regular exhibitions from 1834 onwards. His growing reputation led to his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1842. This was a significant recognition of his standing among his peers.

Nine years later, in 1851, he achieved the distinction of being elected a full Royal Academician (RA), granting him full voting rights and status within the institution. This solidified his position as one of the country's leading artists. He became an active participant in the Academy's affairs, respected for his professionalism and social grace.

The pinnacle of his institutional career came in 1866. Following the death of the previous President, Sir Charles Eastlake (1793-1865), the presidency was offered to Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), arguably the most popular painter in Britain at the time, known for his animal subjects. Landseer, however, declined the honour due to ill health. In the subsequent election, Francis Grant was chosen as President of the Royal Academy (PRA). As was customary, he received a knighthood from Queen Victoria shortly after his election, becoming Sir Francis Grant. He held the presidency with dignity and competence for twelve years until his death, overseeing the Academy's exhibitions and guiding its direction during a period of continued prominence but also emerging challenges from newer artistic movements.

Context and Contemporaries: The Victorian Art World

Sir Francis Grant operated within a vibrant and complex art world. His career coincided with the flourishing of Victorian art, characterized by diverse styles and competing artistic philosophies. While Grant represented the established tradition of portraiture, other significant movements were unfolding. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by artists like John Everett Millais (1829-1896), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), challenged academic conventions with their detailed realism and morally charged subjects. Millais himself would later become a highly successful portraitist and eventually succeed Grant's successor as PRA.

Grant's direct competitors in the field of society portraiture included figures like Sir George Hayter (1792-1871), who also enjoyed royal patronage, particularly earlier in Victoria's reign. The aforementioned Franz Xaver Winterhalter posed significant competition on an international level. Within the Royal Academy itself, Grant worked alongside prominent figures such as the narrative painter William Powell Frith (1819-1909), known for hugely popular contemporary scenes like Derby Day, and the history painter Daniel Maclise (1806-1870). The great landscape painters J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837) were senior figures whose careers overlapped with Grant's early years.

Grant's predecessor as PRA (before Landseer's brief election) was Sir Charles Eastlake, a painter and influential art historian and administrator. His successor, elected after Grant's death in 1878, was Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), later Lord Leighton, a proponent of classical subjects and a central figure of the late Victorian 'Olympian' movement. Anecdotally, Grant is said to have felt somewhat overshadowed by the talent and charisma of the younger Leighton, perhaps sensing the shift in artistic tastes towards the end of his own career. Grant also played a role in guiding younger artists, such as William Watson. His position placed him at the centre of artistic debates and institutional life, navigating the demands of tradition and the emergence of new styles.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Sir Francis Grant remained an active painter and President of the Royal Academy until his final years. He continued to receive prestigious commissions and enjoyed widespread respect, even as artistic fashions began to evolve. His presidency was generally seen as stable and successful, maintaining the Academy's public standing. He oversaw the Academy's move to its current premises at Burlington House in Piccadilly.

He died of heart disease on October 5, 1878, at his country residence, The Lodge, in Melton Mowbray, the town so closely associated with his early sporting pictures. He was 75 years old. His death marked the end of an era for the Royal Academy and for Victorian portraiture.

Sir Francis Grant's legacy is primarily that of the quintessential Victorian society portraitist. His works offer an unparalleled visual chronicle of the British elite during a period of national confidence and global power. His paintings are valued not only for their artistic merit – the skillful likenesses, elegant compositions, and fine technique – but also as historical documents. They capture the appearance, attire, and bearing of the men and women who shaped Victorian Britain.

His paintings are held in major public collections, including the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh, the Royal Collection Trust, Tate Britain, and numerous other museums and galleries across the UK and abroad. While perhaps not considered an innovator on the scale of Turner or the Pre-Raphaelites, Grant masterfully fulfilled the role demanded of him by his time and clientele, creating a body of work that remains impressive in its scope and quality. He stands as a key figure in the history of British art, bridging the gap between the Regency elegance of Lawrence and the changing artistic landscape of the later 19th century.

Conclusion: A Master of His Genre

Sir Francis Grant's journey from a fox-hunting gentleman of depleted means to the Knighted President of the Royal Academy is a remarkable story of talent, ambition, and social adeptness. Lacking formal training, he cultivated his skills to become the most sought-after portrait painter of his generation in Britain, capturing the likenesses of royalty, statesmen, and aristocrats with elegance and precision. His early sporting pictures remain iconic representations of country life, while his vast output of portraits provides an invaluable record of Victorian high society. As an artist and as President of the Royal Academy, Sir Francis Grant left an indelible mark on the art of his time, securing his place as a master within the enduring tradition of British portraiture.