John Hoppner stands as a significant figure in the landscape of British art, particularly during the vibrant and transitional period of the late Georgian era. Active from the late 18th century until his death in the early 19th century, Hoppner established himself as one of London's foremost portrait painters, navigating a competitive artistic scene and securing patronage from the highest levels of society, including the Royal Family. Though sometimes overshadowed in historical narratives by his direct predecessor, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and his chief rival, Sir Thomas Lawrence, Hoppner's contribution to British portraiture is undeniable, marked by a distinctive flair for colour and a sensitivity in capturing the likeness and character of his sitters.

Early Life and Royal Connections

John Hoppner was born in Whitechapel, London, in 1758. His parentage provided an immediate connection to the court; his father was a German-born physician, while his mother served as an attendant to the German-speaking Queen Charlotte, consort of King George III. This proximity to the Royal Household proved advantageous for the young Hoppner. He garnered the attention and favour of King George III from an early age, which facilitated his entry into the Chapel Royal as a chorister.

These royal connections fueled persistent, though unsubstantiated, rumours throughout Hoppner's life that he might have been an illegitimate son of George III. While no concrete evidence supports this claim, the speculation undoubtedly added a layer of intrigue to his public persona and perhaps even aided his early career trajectory. Regardless of the veracity of the rumour, the King's patronage was genuine and provided Hoppner with crucial support during his formative years.

Artistic Training and Early Career

Recognising his artistic inclinations, Hoppner pursued formal training. In 1775, he enrolled as a student at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. His talent was quickly acknowledged; he received a silver medal for drawing from life in 1778, demonstrating his foundational skills. His ambition initially leaned towards landscape painting, a genre gaining popularity in Britain at the time.

However, Hoppner soon shifted his focus towards the more lucrative field of portraiture, perhaps driven by economic necessity as much as artistic preference. His academic progress continued impressively. In 1782, he achieved the Royal Academy's highest honour, the Gold Medal, awarded for his historical painting depicting a scene from Shakespeare's King Lear. This success signalled his capability in narrative composition and figure drawing, skills that would serve him well in his future portrait work, even though he primarily became known for likenesses rather than grand historical subjects.

Rise to Prominence and Royal Patronage

Following his academic successes, Hoppner rapidly established himself as a fashionable portrait painter in London. His studio attracted a clientele drawn from the aristocracy, the gentry, and the burgeoning wealthy merchant class. His early style showed the clear influence of the leading portraitist of the day, Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy. Hoppner emulated Reynolds's rich colouring and compositional grandeur, which appealed to the tastes of the elite.

His most significant patron became the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV. In 1789, Hoppner was appointed Principal Painter to the Prince, a prestigious title that solidified his position within the art establishment and guaranteed a steady stream of high-profile commissions from the Prince's circle. This appointment placed him in direct competition with other favoured artists, most notably Thomas Lawrence, who was also patronised by the Prince and eventually succeeded Hoppner in royal favour.

Hoppner's standing within the artistic community was further cemented by his election to the Royal Academy. He became an Associate (ARA) in 1793 and achieved the status of full Royal Academician (RA) in 1795. Membership in the Academy was not only a mark of peer recognition but also provided exhibition opportunities and enhanced professional status.

Artistic Style and Influences

John Hoppner's artistic style is often characterized by its brilliant use of colour and relatively free, fluid brushwork. While deeply influenced by Sir Joshua Reynolds, particularly in his rich palettes and attempts at capturing the sitter's status and character, Hoppner developed certain individual traits. His handling of paint could be more vigorous and less meticulously blended than Reynolds's, sometimes lending his portraits a sense of immediacy and liveliness.

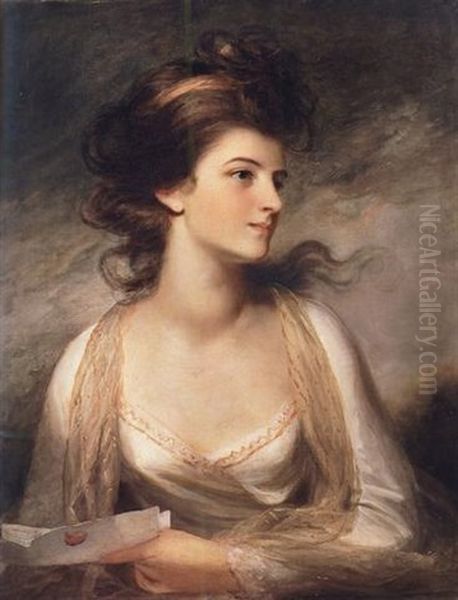

The influence of Thomas Gainsborough, another giant of 18th-century British portraiture, can also be discerned, perhaps in the slightly softer, more feathery application of paint seen in some of Hoppner's female portraits and his sensitivity to fabric textures. Hoppner excelled particularly in the portrayal of women and children. His depictions often combined fashionable elegance with a degree of warmth and intimacy, capturing a sense of personality beneath the societal veneer. His work reflects the transition towards the burgeoning Romantic sensibility, emphasizing feeling and individuality, albeit within the established conventions of society portraiture.

Despite his skill, particularly with colour, critics then and now have sometimes pointed to a lack of profound originality or psychological depth compared to Reynolds or the dazzling technical virtuosity of his rival, Thomas Lawrence. Some historians argue that Hoppner's style, while accomplished and often beautiful, relied heavily on adapting the formulas established by Reynolds, making him a highly competent follower rather than a groundbreaking innovator.

Key Works and Subject Matter

Throughout his career, Hoppner produced a substantial body of work, primarily portraits. His Gold Medal-winning history painting, King Lear (1782), remains an important early work demonstrating his academic training, though few other major history paintings followed. His reputation rests firmly on his portraits.

Among his most celebrated works is the portrait of Lady Cunliffe. This painting is often cited as a prime example of Hoppner's mastery of colour and his ability to create a visually sumptuous image, capturing the elegance and poise of the sitter. It remains one of his best-known pieces.

Another significant work is the Portrait of Sir George Beaumont (c. 1803), now housed in the National Gallery, London. Beaumont was an influential art patron and amateur painter himself, and his relationship with Hoppner was complex; Beaumont reportedly found Hoppner's portrait less refined than the work of Reynolds.

Hoppner was particularly renowned for his group portraits of children, such as The Sackville Children and The Frankland Sisters. The latter became widely known through an engraving by William Ward, demonstrating the importance of printmaking in disseminating artists' work during this period. These works showcase his ability to handle complex compositions and capture the innocence and charm of youth.

Other notable portraits include those of prominent figures such as the Prince of Wales (George IV), the Duchess of York, the Countess of Oxford, Princess Mary, Admiral Lord Nelson, the Duke of Wellington, Sir Walter Scott, and fellow artists like Joseph Farington. He painted figures from across the spectrum of British high society. His Portrait of a Lady as Evelina exemplifies the romanticized approach he sometimes employed. In 1803, he published A Series of Portraits of Ladies, featuring engravings by Charles Wilkin after his paintings, further cementing his reputation as a specialist in female portraiture.

Relationship with Contemporaries

The London art world of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was a dynamic and competitive environment. Hoppner's career unfolded alongside many talented artists. His primary influence, Sir Joshua Reynolds, dominated the scene until his death in 1792. Thomas Gainsborough was another major figure whose landscape sensibility and fluid portrait style offered an alternative to Reynolds's grand manner.

Hoppner's most significant professional relationship was arguably his rivalry with Sir Thomas Lawrence. Both artists vied for the most prestigious commissions and royal favour. Lawrence, younger and possessing a dazzling, almost flamboyant technique, gradually eclipsed Hoppner, especially after Reynolds's death. Their competition was well-known, though they maintained a degree of professional respect, even exchanging portraits of each other.

Hoppner was also a contemporary of other notable portraitists like George Romney, whose elegant, neoclassical style was immensely popular, particularly for female portraits, and the Scottish master Henry Raeburn, known for his robust and characterful depictions. He interacted with fellow Royal Academicians such as William Beechey, another successful portrait painter favoured by the Royal Family, and history painters like the American-born Benjamin West, who succeeded Reynolds as President of the Royal Academy, and the imaginative Henry Fuseli. Engravers like William Ward and Charles Wilkin played a crucial role in popularizing Hoppner's images through prints. These interactions, whether collaborative or competitive, shaped Hoppner's career and place within the artistic milieu.

Critical Reception and Controversies

John Hoppner enjoyed considerable success and popularity during his lifetime. He commanded high prices for his portraits and was sought after by the elite. His appointment as Principal Painter to the Prince of Wales was a clear mark of his high standing. His works were regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy, attracting public attention.

However, his critical reception was not uniformly positive, and certain controversies touched his life. The persistent rumour about his being George III's illegitimate son, while perhaps adding to his fame, was an undercurrent throughout his career. More pertinent to his art was the recurring criticism that his style was overly derivative, particularly of Reynolds. Figures like Sir George Beaumont voiced opinions that Hoppner lacked the subtlety and refinement of his great predecessor. Compared to the rising star of Lawrence, Hoppner's work could seem less brilliant or innovative to some contemporary eyes.

Biographical details also include his marriage to Phoebe Wright, the daughter of Patience Wright, a celebrated American-born sculptor known for her wax modelling and republican sympathies. Phoebe herself was an artist, exhibiting floral and mythological subjects. The snippet mentioning his wife's support for the American Revolution points to the politically charged atmosphere of the time, though the extent to which this directly impacted Hoppner's career or generated significant controversy for him personally is not fully detailed in the provided context.

Later Life and Legacy

John Hoppner continued to work prolifically until the end of his life, maintaining a busy portrait practice despite increasing competition from Lawrence and suffering from ill health in his later years. He died in London on January 23, 1810, at the relatively young age of 52.

His legacy is that of a highly skilled and successful portrait painter who bridged the era of Reynolds and the ascendancy of Lawrence. While perhaps not possessing the revolutionary impact of Gainsborough or the consistent brilliance of Lawrence, Hoppner was a master colourist whose works often possess great charm, elegance, and visual appeal. He captured the likeness of a generation of British aristocracy and gentry, leaving behind a valuable record of Georgian society.

His paintings are held in numerous major public collections worldwide, including the Royal Collection (St. James's Palace, Windsor Castle), the National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery in London, the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Galleries of Scotland, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and many other institutions and private collections. His work continues to be appreciated for its technical accomplishment and its representation of a key period in British art history.

Conclusion

Sir John Hoppner remains an important figure in the narrative of British portraiture. Emerging under the shadow of Reynolds and competing fiercely with Lawrence, he carved out a highly successful career, becoming a favourite of the Prince of Wales and a full Royal Academician. Celebrated for his rich use of colour and his sensitive portrayals, especially of women and children, his work embodies the elegance and shifting sensibilities of the late Georgian period. While subject to criticism regarding originality, his skill and productivity ensured his place as one of the leading artists of his time, leaving behind a significant body of work that continues to engage viewers today.