Stefano della Bella stands as one of the most prolific and engaging figures in 17th-century Italian art. Born in Florence in 1610 and passing away in the same city in 1664, his life spanned a crucial period of artistic transition from the late Renaissance and Mannerism into the full flourish of the Baroque. While trained in painting, Della Bella's enduring legacy rests firmly on his extraordinary output as an etcher and draughtsman. He produced over 1400 distinct etchings, a staggering number that captures an incredibly diverse range of subjects, offering a vivid panorama of his time. His work provides invaluable insights into the courtly life, military conflicts, urban landscapes, and even the scientific currents of the Baroque era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Stefano della Bella was born into an artistic environment in Florence on May 18, 1610. His father, Francesco della Bella, was a sculptor, suggesting that an appreciation for the visual arts was present in the household from Stefano's earliest years. His brothers also pursued artistic careers, reinforcing the family's connection to the creative trades of the city. This familial background likely provided both encouragement and initial exposure to artistic practices.

His formal training, however, did not begin with the grander arts of painting or sculpture. Instead, Della Bella was initially apprenticed to a goldsmith, possibly Orazio Valenti. This early training would have instilled in him a meticulous attention to detail and a mastery of fine line work, skills that would prove invaluable in his later career as an etcher. The precision required in goldsmithing translated well to the delicate process of incising lines onto a copper plate.

Della Bella soon gravitated towards painting and drawing. He sought further instruction, studying painting under several Florentine masters. Among his teachers were Giovanni Battista Vanni and Cesare Dandini. Vanni was himself an accomplished painter and etcher, and likely provided crucial guidance. Dandini, a prominent Florentine painter known for his elegant figures, would have exposed Della Bella to the prevailing local styles, which still carried echoes of late Mannerist grace.

Crucially for his future specialization, Della Bella also studied the art of etching under the guidance of Remigio Cantagallina. Cantagallina was himself a significant printmaker, known particularly for his landscapes and festival scenes. He had also been, significantly, a teacher of the highly influential French artist Jacques Callot during Callot's time in Florence. This connection provided Della Bella with a direct lineage to advanced etching techniques and styles.

The Influence of Jacques Callot and Developing a Personal Style

The impact of Jacques Callot (c. 1592–1635) on the young Stefano della Bella cannot be overstated. Callot, originally from Lorraine but active for a significant period in Florence under Medici patronage, revolutionized etching with his innovative techniques and dynamic compositions. He employed hard grounds and multiple bitings to achieve unprecedented detail and tonal variation, and his prints, often depicting military scenes, festivals, and commedia dell'arte figures, were immensely popular throughout Europe.

Della Bella clearly absorbed Callot's influence, particularly in his early works. Echoes of Callot's small, lively figures, his panoramic compositions, and his somewhat calligraphic line work can be discerned. However, Della Bella was not merely an imitator. He rapidly assimilated Callot's technical advancements and stylistic approaches but began to forge his own distinct artistic identity.

While Callot's figures often possessed a certain stylized, almost fantastical quality, Della Bella moved towards a greater naturalism and a more nuanced observation of the world around him. His lines became perhaps less overtly calligraphic and more descriptive, focusing on capturing textures, light, and atmosphere with remarkable subtlety. He developed a unique Baroque sensibility, characterized by dynamic movement, rich detail, and a keen eye for the specifics of contemporary life, setting his work apart from his influential predecessor.

Patronage and the Medici Court

Like many Florentine artists of his time, Stefano della Bella benefited significantly from the patronage of the powerful Medici family, the Grand Dukes of Tuscany. Florence, though past its Renaissance peak, remained an important cultural center under their rule. Della Bella secured a position at the Medici court, serving as a designer and printmaker. This provided him with a degree of financial stability and access to prestigious commissions.

His role involved documenting court life, particularly the elaborate festivals, theatrical performances, and ceremonial entries that were characteristic of Baroque princely courts. These events were designed to display the wealth, power, and cultural sophistication of the ruling dynasty. Della Bella's etchings captured the ephemeral splendor of these occasions with remarkable vivacity and detail.

A notable example includes prints depicting Medici feasts, sometimes referred to generally or perhaps specifically relating to works like the Banquet of the Piacevoli. These prints often show large gatherings, intricate temporary architecture, and numerous small figures engaged in celebration, all rendered with his characteristic precision. He also created designs for decorative objects and potentially contributed to stage designs, showcasing his versatility within the court environment. His work for the Medici helped solidify his reputation within Florence and provided a foundation for his later international career.

Roman Sojourn: Expanding Horizons

Seeking to broaden his artistic education and experience, Della Bella traveled to Rome around 1633-1636. Rome, as the center of the Catholic Church and a hub of artistic innovation, attracted artists from all over Europe. It offered exposure to the masterpieces of antiquity, the High Renaissance, and the burgeoning Baroque movement spearheaded by artists like Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona.

During his time in Rome, Della Bella diligently studied both ancient ruins and the works of contemporary masters. This period was crucial for his development, allowing him to absorb the grandeur and dynamism that characterized Roman Baroque art. He produced numerous drawings and etchings based on his observations.

Among the significant works stemming from this period are series of landscape prints, such as the Six Views of Rome and the Six Views of the Roman Campagna. These etchings demonstrate his growing skill in rendering atmospheric effects, architectural details, and the picturesque qualities of the Italian landscape. They showcase his ability to combine topographical accuracy with artistic sensibility, capturing the unique light and character of the Roman environment. His Roman experience undoubtedly enriched his visual vocabulary and technical repertoire.

Years in Paris: Royal Commissions and Wider Fame

A pivotal phase in Della Bella's career began around 1639 when he accompanied the Medici ambassador to Paris. He ended up staying in the French capital for over a decade, until approximately 1650. This period marked the height of his international fame and productivity. Paris, under King Louis XIII and his powerful minister Cardinal Richelieu, was becoming a major European political and cultural center, rivaling Rome.

In Paris, Della Bella found ample opportunities and patronage. He received commissions directly from Cardinal Richelieu and subsequently from the royal court under the young Louis XIV and his regent, Cardinal Mazarin. His skills were particularly valued for creating commemorative prints celebrating military victories and significant political events.

One of his most famous series from this time documents the Siege of Arras (1640), a significant event in the Franco-Spanish War (part of the larger Thirty Years' War). These prints combine detailed topographical views of the siege operations with lively depictions of military life, showcasing his ability to handle complex, multi-figured compositions on a grand scale. He also produced prints depicting royal ceremonies, allegories, and views of Paris.

During his Parisian years, Della Bella interacted closely with the city's thriving print market. He collaborated with influential publishers such as Pierre Mariette I and François Langlois (also known as Ciartres). While competition existed between these publishers, their activities helped disseminate Della Bella's work widely, not only within France but across Europe. His elegant and detailed style found great favor with French collectors and artists.

Dutch Interlude and Rembrandt's Shadow

While based primarily in Paris during the 1640s, Della Bella also undertook journeys, including a significant trip to the Netherlands, likely visiting Amsterdam around 1647. The Dutch Republic was then in its Golden Age, a flourishing center of commerce, science, and art. This visit exposed Della Bella to a different artistic milieu, one dominated by realism, genre scenes, and the profound psychological depth found in the work of artists like Rembrandt van Rijn.

The influence of Dutch art, particularly the etchings of Rembrandt, is discernible in Della Bella's work following this period. While Della Bella never adopted Rembrandt's deeply expressive and often raw style wholesale, he seems to have absorbed lessons in the handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and atmospheric effects. Some scholars suggest a greater subtlety in tonal gradations and a heightened sense of atmosphere in his later landscapes and genre scenes, potentially reflecting his Dutch experience.

This exposure to the Dutch masters added another layer to Della Bella's already sophisticated style. It demonstrated his openness to different artistic traditions and his continuous effort to refine his craft by observing the best contemporary practices, even those outside the dominant Italian and French schools.

Return to Florence and Later Career

Around 1650, Stefano della Bella returned to his native Florence. He resumed his service to the Medici family, who welcomed back their now internationally renowned artist. His reputation secured, he continued to receive commissions and enjoyed a respected position in the Florentine art world.

One of his duties included providing instruction to the younger members of the Medici family. Notably, he served as a drawing master to Cosimo III de' Medici, who would later become Grand Duke of Tuscany. This role highlights the esteem in which he was held and his recognized mastery of draughtsmanship.

In his later years, Della Bella continued to produce etchings, though perhaps not with the same intensity as during his Parisian decade. His subjects remained diverse, revisiting themes like landscapes, animals, and allegorical scenes, often imbued with the maturity and technical refinement honed over decades of practice. Sadly, his later life was marked by illness. He suffered a stroke which likely impaired his ability to work in his final years. Stefano della Bella died in Florence on July 12, 1664, leaving behind a vast and influential body of work.

Mastery of Etching: Technique and Subjects

Stefano della Bella's fame rests squarely on his exceptional skill as an etcher. He mastered the technical intricacies of the medium, employing fine lines, delicate cross-hatching, and controlled biting to achieve a remarkable range of tones and textures. His plates are characterized by their clarity, precision, and often astonishing level of detail, especially considering the frequently small scale of his figures.

His subject matter was extraordinarily broad, reflecting the diverse interests of the artist and his patrons, and providing a rich tapestry of 17th-century life:

Military Scenes and Sieges: Following Callot's example but with his own detailed approach, Della Bella depicted battles, encampments, and sieges, such as the aforementioned Siege of Arras. Works like The Portrait of a Warrior or Death on the Battlefield capture the drama and human cost of conflict.

Festivals and Courtly Life: He excelled at recording the pageantry of the Baroque court, including processions, tournaments, theatrical performances (he designed sets), and banquets like the Banquet of the Piacevoli. These prints are invaluable historical documents of court culture.

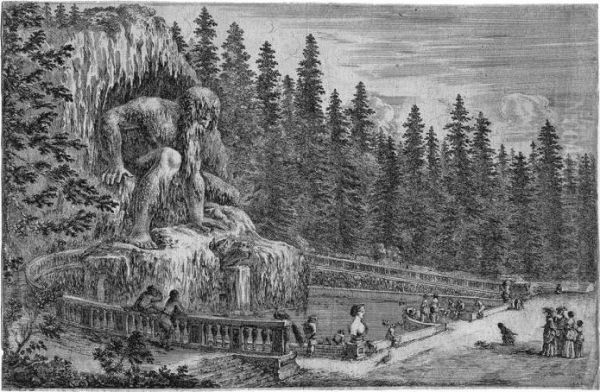

Landscapes and City Views: From his Roman views to depictions of the Arno River in Florence or Parisian landmarks, Della Bella showed a keen sensitivity to place. His landscapes often include charming details of rural life or travelers, as seen in Landscape with animals. Architectural accuracy was also a feature, evident in works like Temple of Antinous or the impressive Statue colossale de l’Apennin (depicting Giambologna's sculpture).

Animals and Hunting Scenes: Della Bella had a particular fondness for depicting animals, rendering them with accuracy and character. He produced series of prints featuring horses, dogs, birds, and exotic creatures like elephants (Head of an Elephant). Hunting scenes were also a recurring theme.

Daily Life and Genre: Alongside grand events, he captured scenes of everyday life, markets, travelers, and peasants, often with a light and observant touch.

Allegory, Mythology, and Religion: He treated traditional subjects like The Fall of Phaeton or Pan et Syrinx, often incorporating them into landscape settings. Religious themes appear, though less frequently than secular subjects.

The Macabre: Like Callot, Della Bella explored themes of death, notably in his powerful series known as the Five Deaths and individual prints like Death Carrying off a Child, reflecting Baroque preoccupations with mortality.

Scientific Illustration: Demonstrating his engagement with the intellectual currents of his time, Della Bella provided the frontispiece illustration for Galileo Galilei's groundbreaking Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), depicting Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Copernicus in discussion.

Artistic Style: From Mannerist Grace to Baroque Vivacity

Stefano della Bella's artistic journey mirrors the broader stylistic shifts occurring in Italian art during his lifetime. His early work, produced under the influence of Florentine teachers like Dandini and the initial impact of Callot, retains elements of late Mannerist elegance – elongated figures, graceful poses, and intricate compositions.

However, his exposure to Roman Baroque and his own developing sensibilities pushed him towards a more dynamic and naturalistic style. While always maintaining a remarkable delicacy of line, his work increasingly embraced Baroque characteristics: dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), energetic movement within compositions, a focus on capturing fleeting moments, and a deep engagement with the observable world.

He achieved a unique synthesis. His prints combine the meticulous detail inherited from his goldsmith training and Callot's technique with a Baroque sense of liveliness and atmospheric depth, possibly enhanced by his encounter with Dutch art. He avoided the heavy emotionalism of some Baroque painters, favoring instead a refined, observant, and often witty approach. His ability to manage vast numbers of tiny figures within complex scenes, each rendered with individuality, is a hallmark of his mature style.

Legacy and Influence

Stefano della Bella was highly regarded during his lifetime, and his influence extended throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly in France. His etchings were widely collected and copied. French printmakers like François Collignon and Israël Silvestre clearly show his impact in their topographical and illustrative works. His elegant style also resonated with designers and artisans, and its echoes can be traced into the Rococo period.

His direct students, such as Giovanni Battisti and Michele Lladó, carried on aspects of his style, though none achieved his level of fame or prolific output. His interactions with contemporaries like Baccio del Bianco, though sometimes debated by scholars in terms of direct collaboration versus stylistic emulation, point to his active participation in the Florentine art scene.

Despite his contemporary success, Della Bella's reputation suffered a period of neglect during the 19th century, as tastes shifted away from the perceived frivolity of Baroque court art. However, the 20th century saw a resurgence of interest, particularly from the 1960s onwards, with major exhibitions and scholarly publications reassessing his significant contribution to the art of printmaking. He is now recognized as a major figure in Baroque art, admired for his technical brilliance, his vast range of subjects, and the captivating window his work offers onto 17th-century European life.

Collections and Enduring Significance

Today, Stefano della Bella's works are held in the collections of major museums and print rooms around the world, attesting to his enduring importance. Significant holdings of his drawings and prints can be found at:

The Uffizi Gallery in Florence (especially rich in drawings)

The Louvre Museum in Paris (also strong in drawings)

The Royal Collection Trust at Windsor Castle

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

The British Museum in London

The Albertina in Vienna

The Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica in Rome

The Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

These collections preserve the legacy of an artist whose meticulous technique, keen observation, and boundless curiosity allowed him to capture the spirit of the Baroque age with unparalleled charm and detail. Stefano della Bella remains a pivotal figure in the history of etching, a master draughtsman whose thousands of images continue to delight and inform viewers centuries after their creation. His work stands as a testament to the power of printmaking to document, interpret, and animate the world.